Rehab Rounds: Dissemination of Educational Classes for Families of Adults With Schizophrenia

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: Despite the well-documented efficacy of psychoeducational and behavioral approaches in family interventions for persons with serious mental illness (1), clinicians have rarely included these methods in their professional repertoires (2). Journal publications, books, continuing education courses, and advocacy by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and its local affiliates have induced few professionals to provide family psychoeducation.Mental health professionals adopt new services primarily for the same reason that employees of any firm change their work practices—namely, because the authority structure and contingencies of reinforcement that impinge on their daily activities are altered in a direction favoring change. Therefore, administrative clout must be brought to bear to mandate the inclusion of family psychoeducation in the spectrum of services provided by a clinic, mental health center, community support program, hospital, or independent provider (3). In addition, the consequences of clinicians' services must differentially reward the use of these methods of involving families in services for the seriously mentally ill (4). Differential rewards could come from performance standards and evaluations, performance-based pay, third-party payments, positive feedback from clients and families, public recognition, and increased self-efficacy.Use of in-service training or workshops to persuade clinicians to adopt innovations such as family psychoeducation and family management techniques has a checkered and unremarkable track record. For example, brief training has failed completely in efforts to bring about adoption of family interventions. On the other hand, more extended efforts to train staff, including organizational consultation, have been more successful (5). In one study, two days of staff training produced no change, whereas intensive training over several months resulted in the implementation of new family programs at the majority of study sites (6). Staff from sites that received extensive training but did not adopt the interventions rated family interventions as less consistent with their professional philosophy and agency norms and identified more obstacles to intervention, notably intense work pressure, uncertainty about financing the intervention, agency bureaucracy, lack of leadership, skepticism about the interventions, problems with confidentiality, and inability to provide services in the evenings or on weekends (6).In this Rehab Rounds column, Amenson and Liberman describe a three-phase, multilevel dissemination effort designed to overcome the above-mentioned barriers to the incorporation of family psychoeducation into the routine care provided at community mental health centers in an ethnically diverse urban setting. Moreover, Amenson and Liberman demonstrate the need for continued support and nurturance of the project to ensure that the original enthusiasm associated with a novel intervention is not lost once it becomes a standard part of treatment.

Working With Families was a project launched in 1995 to introduce family psychoeducation in the Los Angeles County Mental Health Department by using two interventions in tandem: gaining the commitment of top management and conducting extensive staff training. The management intervention was initiated by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill-Los Angeles County (NAMI-LA County) in their monthly meetings with the director of Los Angeles County's Department of Mental Health. For three years, NAMI-LA County, representing 17 NAMI affiliates, targeted professional training in working with families as a top priority for improvement of the mental health system. They consistently presented this need to the top management of the department, and they succeeded in obtaining a commitment to fund and support the training.

A task force composed of staff from the department's training division, NAMI leaders, and line-level clinicians was formed to design the training program. The task force recommended that every staff member of the county Department of Mental Health receive a one-day training session on the importance of educating, supporting, and collaborating with families and that every clinical site establish a family service team of at least two professionals who would receive nine months of intensive training and supervised practice in family psychoeducation.

The training of family service teams was made the first priority. After a national search, Pacific Clinics Institute in Pasadena, California, was chosen to provide the training. This choice was made on the basis of the recommendations of experts in family psychoeducation and the evaluations of families and professionals who had been trained by the first author over the previous 18 years.

Top management promoted the training in three ways: by designating family education as one of the 17 required services at each mental health program, by frequently discussing the importance and benefits of the training, and by making admission into the training a competitive process that required trainees to be nominated by their program directors. Thirty-nine psychologists, social workers, and nurses were selected. Only 38 percent of the trainees were Euro-American, reflecting the diverse, multiethnic fabric of the Los Angeles area. Languages spoken by trainees included Spanish, Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese, Korean, Hindi, Persian, Tagalog, and Vietnamese.

Conducting the training

The training was organized into three phases. In phase 1, participants received 21 hours of didactic training over a seven-week period given by the first author along with June Husted, Ph.D. (a family member and psychologist), and panels of families and consumers who served as guest faculty. Research on family interventions, methods for engaging and collaborating with families, and educational, supportive, problem-solving, and skill-building interventions were presented. Trainees were required to read 230 pages of material and to complete written assignments to practice the skills that were taught. Reading and practice assignments were reviewed each week, and participants received written feedback on each completed assignment.

To be admitted to phase 2, participants had to have successfully completed the assignments from phase 1 and to have agreed to form and teach a family education class at their home site. Twenty-three trainees were selected. Phase 2 was composed of six sessions lasting a total of 18 hours. This phase was based on the published curriculum, Schizophrenia: A Family Education Curriculum (7) and Schizophrenia: Family Education Methods (8). The curriculum is the fourth edition of a family education course that has evolved over 15 years and has been distributed to NAMI affiliates in 40 states. It consists of 159 slides and corresponding lecture notes for a 12-hour course on schizophrenia. Although the course was designed to educate families, it is also appropriate for community and paraprofessional caregivers. The research and theoretical bases of family education, formation and recruitment for a family education class, role of the family educator, educational methods, and specific exercises for each session of the curriculum constituted the learning activities during the six sessions of phase 2 training.

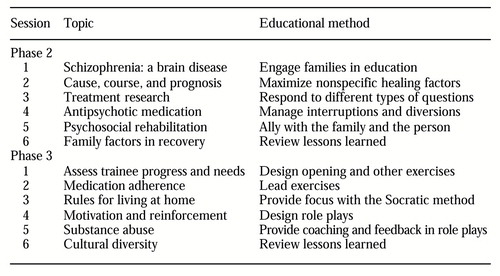

During the first half of each phase 2 session, the trainer discussed a session of the curriculum and typical family concerns and issues related to each topic. In the second half, the trainer demonstrated education methods and had trainees practice them in highly structured role plays. For each method, the trainer first demonstrated effective and ineffective techniques. All trainees gave feedback to the trainer before they gave feedback to each other. The trainer modeled receptivity to feedback and shaped the feedback he received into positive statements. For example, "You're too quiet, too dull. I lost interest" was restated as "When you spoke louder, gestured more, and made eye contact with the audience, I listened more eagerly." The topics and educational methods for each session of phases 2 and 3 are listed in Table 1.

During phase 2, trainees formed four surrogate classes of five or six trainees, each of whom played the role of a family member while trainees took turns presenting a 15-minute lecture from the curriculum to the "class." Using a lecture skills feedback form, the class members described and reinforced trainee behaviors that met each of the lecture tasks and competencies. The lecture tasks were the following:

• Communicate interest in and empathy toward the audience

• Demonstrate organization and knowledge of the material

• Provide a conceptual map for the audience

• Present concepts clearly and emphasize key concepts

• Use stories, analogies, or pictures to illustrate key concepts

• Use self-disclosure and personal experience to enhance engagement by family members in the learning

• Use strong opening and closing statements

• Provide a handout that summarizes key points.

The trainer circulated among classes to provide feedback himself and to promote positive feedback from the surrogate members of each class to the trainee. Requiring feedback to be positive statements of behaviors that were or could be exhibited promoted a cohesive learning atmosphere that was an important influence on the success of the training.

In phase 3, also composed of six sessions totaling 18 hours, most trainees used Schizophrenia: A Family Education Curriculum for teaching their first course with families individually at their home sites. Phase 3 provided additional training and supervision on family education and consultation. Each session was divided between teaching specific methods for handling common family problems and practicing specific educational methods. For example, in session 2, the trainer taught family interventions for promoting medication adherence by providing a lecture and readings on the topic, brainstorming solutions for problems that trainees had encountered, and demonstrating and role playing the proposed solutions.

Each trainee designed and led an exercise and a role play for a "class" of peers. Trainees could choose exercises and role plays from Schizophrenia: Family Education Methods or create their own. Using feedback forms, class members described trainees' behaviors that promoted and enhanced learning among families. The behaviors were the following:

• Communicate the goals for the exercise

• Give clear written instructions

• Give clear oral instructions

• Demonstrate or model the task

• Allocate and effectively use time

• Encourage participation

• Remain on task and on schedule

• Summarize the lessons learned from the exercise.

Trainees regularly reported on the progress of the family education classes they were teaching at their home sites. Successes were praised and used to reinforce key methods. Problems were discussed in a group problem-solving format in which trainees brainstormed a number of solutions. The trainee who presented the problem then selected one of these interventions to use in his or her class. This format was especially useful for modifying class recruitment, structure, and methods to work with non-English-speaking families.

Evaluation

On completing the course, participants anonymously completed a questionnaire that elicited their perception of the value of the training and their satisfaction with it. On a 5-point Likert scale with 5 indicating the most value and satisfaction, the average rating was 4.99. Anecdotal comments highlighted the importance of the trainer's competence, the duration of the training, and the provision of a combination of multimodal presentations, demonstrations, and practice of skills in the classroom as having facilitated the trainees' implementation of the program at their mental health centers.

Fifteen of the twenty-three clinicians who participated in the training were interviewed nine months later by a research associate who had no involvement in the project. The interview included questions soliciting participants' views of the relevance of the training, their confidence in employing the family education procedures, and their actual use of the procedures in their clinical work since the training had ended. Almost all respondents rated the 12 topical areas taught in the training as "highly relevant." A few respondents rated some topics as "somewhat relevant," and only one rated two topics as being of "little relevance." All fifteen respondents indicated that by the end of the training, they acquired knowledge in the topic areas, and all but one respondent claimed to have confidence in their ability to use all of the topics. All respondents also indicated that they had been able to use and apply their knowledge and technical competence at their mental health facilities in at least eight of the ten topic areas.

The proportions of clinicians who led family education courses nine months before and after the training project were 44 percent and 87 percent, respectively. The number of family education courses given by clinicians nine months before and after the project were 41 and 156, respectively. All 15 respondents indicated that they planned to teach family education courses in the future.

Clinician-trainees attributed their competence and confidence in using family psychoeducation skills to the active discussions, exercises, and role plays in the training project. The lecture slides and training materials were viewed as very helpful and user-friendly. The structured training methods facilitated their ability to communicate with and engage families in education groups. Factors that helped the trainees apply the skills in their mental health settings included administrative support from top management, a congruent treatment philosophy in their clinics, the availability of external consultation, and encouragement from a respected colleague to use the skills.

Two trainees adapted the use of the family education courses in Japan, and the curricula have been published in Japanese (9). There has not been any direct observation of the trainees' use of skills to verify the quality or frequency of the family education courses being taught.

The success of the project was due to five main factors: the persistent advocacy of NAMI-LA County, the support of top management, the nine-month duration of training, the quality of the trainees (described as the crème de la crème of Department of Mental Health), and the skill of the trainer, including his ability to alter the pacing and format to meet the evolving needs of trainees as they began to teach courses at their work sites. An additional element of success was that one trainee was the NAMI-Whittier president who taught the NAMI Family to Family course. Her enthusiastic participation as a trainee earned the respect of all trainees. From this position, she was able to interject elements of family experience and coping efforts that enhanced trainees' abilities to engage, educate, and support families.

In 2000, the Working With Families project included 60 new trainees. The success of the Los Angeles County project led to three smaller replications. With the support of NAMI-San Diego, the San Diego County Department of Mental Health purchased the curriculum and hired the senior author to train two cohorts of 20 staff members each. The Georgia Therapeutic Education Association provides intensive training using Schizophrenia: Family Education Methods as the text in a course that leads to certification as a mental illness educator. Hawaii State Hospital has hired the senior author to help create a comprehensive family psychoeducation program based on the curricula. As an extension to Working With Families, the first author has written Family Skills for Relapse Prevention (10), a curriculum for teaching relapse prevention to multifamily classes that include the person with a mental illness. In the initial field test of the curriculum with the families of persons with mental illness, no rehospitalization occurred during the first six months after the course.

Afterword by the column editors: A plethora of studies have documented the obstacles that must be overcome to disseminate complex psychosocial interventions from academia to the practitioner community (11). Specific strategies that have been found to be helpful in overcoming the practitioner and institutional roadblocks to adoption of innovations have included adapting the innovation so it is user-friendly; providing interpersonal contact, demonstrations, and support from the innovator to the practitioner; enhancing the organizational support for the innovation from management and key stakeholders; and permitting the practitioner to "reinvent" the innovation to fit it into the constraints and resources particular to the practice setting. The dissemination approach described in this column uses each of these strategies in creative ways to facilitate family collaboration with mental health professionals. As with other staff training programs (12), it is likely that only the extensive training provided in the current effort at staff development will have long-term practical results.

An additional method for enhancing family services was proposed recently by Mueser and Fox (13). They suggested that community mental health centers designate an individual as the director of adult family services, in the same way that organizations establish directors of vocational rehabilitation and dual disorders treatment programs. By establishing such a funded position with the authority to see that family services are provided, the mental health center would formally acknowledge the importance of families and would hold itself accountable for providing evidence-based family services to clients. The support of such an initiative by state and local funding agencies would ensure that truly collaborative, family-oriented services became a routine part of the care received by persons with serious mental illness. This recommendation has been implemented by Riverside County (California) Mental Health Services, with promising results (personal communication, McAndrews G, December 2000).

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of Karen Blair, M.S., in conducting the follow-up survey.

Dr. Amenson is director of the Pacific Clinics Institute, 909 South Fair Oaks Avenue, Pasadena, California 91105-2625 (e-mail, [email protected]). He is also assistant professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavorial sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, where Dr. Liberman is professor. Dr. Liberman and Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Topics and methods taught in the sessions of phases 2 and 3

1. Dixon L, Lehman AF: Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631-643, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Steinwach DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results for Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11-20, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Liberman RP, Corrigan PW: Implementing and maintaining behavior therapy programs, in Behavior Therapy in Psychiatric Hospitals. Edited by Corrigan PW, Liberman RP. New York, Springer, 1994Google Scholar

4. Moss GR: A biobehavioral perspective on the hospital treatment of adolescents, in ibidGoogle Scholar

5. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233-238, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Amenson CS: Schizophrenia: A Family Education Curriculum. Pasadena, Calif, Pacific Clinics Institute, 1998Google Scholar

8. Amenson CS: Schizophrenia: Family Education Methods. Pasadena, Calif, Pacific Clinics Institute, 1998Google Scholar

9. Amenson CS, Matsushima Y, Arai Y: Schizophrenia: A Family Education Curriculum [Japanese translation]. Tokyo, Seiwa Shoten, 2000Google Scholar

10. Amenson CS: Family Skills for Relapse Prevention. Pasadena, Calif, Pacific Clinics Institute, 1998Google Scholar

11. Backer TE, Liberman RP, Kuehnel TS: Dissemination and adoption of innovative psychosocial interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 54:111-118, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Farhall J, Webster B, Hocking B, et al: Training to enhance partnerships between mental health professionals and family caregivers: a comparative study. Psychiatric Services 49:1488-1490, 1998Link, Google Scholar

13. Mueser KT, Fox L: Family-friendly services: a modest proposal [letter]. Psychiatric Services 51:1452, 2000Link, Google Scholar