Effects of Clozapine, Olanzapine, Risperidone, and Haloperidol on Hostility Among Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study compared the specific antiaggressive effects of clozapine with those of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol. METHODS: A total of 157 inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and a history of suboptimal treatment response were randomly assigned to receive clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol in a double-blind 14-week trial. The trial was divided into two periods: eight weeks during which the dosage was escalated and then fixed, and six weeks during which variable dosages were used. The hostility item of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was the principal outcome measure. Covariates included the items that reflect positive symptoms of schizophrenia (delusions, suspiciousness or feelings of persecution, grandiosity, unusual thought content, conceptual disorganization, and hallucinations) and the sedation item of the Nurses Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (NOSIE). RESULTS: Patients differed in their treatment response as measured by the hostility item of the PANSS. The scores of patients taking clozapine indicated significantly greater improvement than those of patients taking haloperidol or risperidone. The effect on hostility appeared to be independent of the antipsychotic effect of clozapine on other PANSS items that reflect delusional thinking, a formal thought disorder, or hallucinations and independent of sedation as measured by the NOSIE. Neither risperidone nor olanzapine showed superiority to haloperidol. CONCLUSION: Clozapine has a relative advantage over other antipsychotics as a specific antihostility agent.

Some patients who are diagnosed as having schizophrenia are occasionally hostile and violent. Violent or threatening behavior is a frequent reason for admission to a psychiatric inpatient facility. If such behaviors continue after admission they can prolong hospitalization and interfere with discharge.

Several retrospective studies have shown a decrease in the number of violent episodes and a decrease in the use of seclusion or restraint among inpatients with schizophrenia after they begin treatment with clozapine (1,2,3,4,5,6,7). These reductions in the occurrence of hostility (8) and aggression (9) after clozapine treatment were selective in the sense that they were statistically independent of the general antipsychotic effects of clozapine. Thus, although no prospective controlled studies of the antiaggressive effects of clozapine have been conducted, the preponderance of retrospective evidence indicates that clozapine reduces aggressive behavior among persons who have schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and that these effects cannot be fully explained by general antipsychotic effects.

Risperidone also was shown to have a selective effect on hostility, as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (10), that was superior to that of haloperidol (11) among patients with schizophrenia who were enrolled in the North American trial of risperidone (12). However, this effect was not evident in a retrospective case-control study of 27 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder whose average dosage of risperidone was 6.8 mg a day (13). A similar response to risperidone and to conventional antipsychotics was found among these patients, as measured by the use of seclusion and restraint. Another study found risperidone to be no different from typical neuroleptics in controlling aggressive behavior in a group of 20 forensic patients with chronic schizophrenia who were taking at least 6 mg of risperidone a day (average dosage not reported) (14).

Thus studies of clozapine, and to a lesser extent of risperidone, suggest that these agents may have specific antiaggressive properties. However, the evidence is based largely on uncontrolled, open-label retrospective studies and anecdotal case reports. The studies varied in their selection of subjects and in their procedures, and it is difficult to compare their results (15).

The antiaggressive effects of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine have not been compared directly in a controlled prospective study. The data we report in this article were obtained during a large-scale multicenter prospective double-blind trial that was designed to examine the efficacy of three atypical antipsychotics as well as haloperidol in a single sample based on uniform patient selection criteria, including a history of suboptimal treatment response (unpublished data, Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al, 2000).

We present the results of a study that tested the secondary hypothesis that a reduction in the score on the hostility item of the PANSS would occur during treatment with clozapine or olanzapine, that the reduction would be greater than that observed during treatment with risperidone, and that treatment with haloperidol would yield the smallest reduction in score on the hostility item. We hypothesized that the reduction in hostility would be selective in the sense that it would be independent of the effect on other items from the PANSS that reflect positive symptoms of schizophrenia.

Methods

This was a prospective, double-blind, 14-week trial in which inpatients at four state psychiatric hospitals—two in New York and two in North Carolina—were randomly assigned to receive clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. All patients met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, had a history of suboptimal treatment response, were between the ages of 18 and 60 years, and had a minimum score of 60 on the PANSS. (Possible scores range from 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating more severe pathology. Scores above 130 are uncommon and represent very severe pathology.)

Suboptimal response to previous treatment was defined by two criteria, both of which were present among the study participants. The first criterion was persistent positive symptoms—hallucinations, delusions, or marked thought disorder—after at least six contiguous weeks, currently or documented in the past, with one or more conventional antipsychotics at dosages equivalent to at least 600 mg of chlorpromazine a day. The second criterion was a poor level of functioning over the previous two years, defined as a lack of competitive employment or of enrollment in an academic or vocational program and absence of age-expected interpersonal relationships involving ongoing regular contact outside the biological family.

Excluded from the study were patients who had a history of not responding to clozapine, risperidone, or olanzapine, defined as an unambiguous lack of improvement despite an adequate trial of risperidone or olanzapine for at least six weeks or clozapine for at least 14 weeks; a history of intolerance to any of the study drugs; or receipt of a depot antipsychotic during the 30 days before study entry.

The patients provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study. Institutional review board approval was obtained at all study sites.

The trial was divided into two periods. Period 1 lasted eight weeks, during which the dosage of antipsychotic drug was escalated and then fixed. During period 2, which lasted six weeks, variable dosages were used. Before period 1, concomitant medications, such as mood stabilizers and antidepressants, were gradually phased out. During the first week of period 1 —cross-titration week—the prestudy antipsychotic was gradually discontinued, and the dosages of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol were usually escalated to the target daily doses—20, 8, and 20 mg, respectively—where they remained until the end of period 1. For clozapine, patients were scheduled to reach the target daily dose of 500 mg on day 24; the dosage then remained fixed until the end of period 1. These dosage schedules were adjusted on the basis of the patient's clinical status, including side effects. The mean±SD daily doses achieved in period 1 were 401.6±160.4 mg for clozapine, 19.6±2.1 mg for olanzapine, 7.9±2.1 mg for risperidone, and 18.9±3.1 mg for haloperidol.

During period 2 the daily dose of antipsychotic was allowed to vary within the ranges of 200 to 800 mg for clozapine, 10 to 40 mg for olanzapine, 4 to 16 mg for risperidone, and 10 to 30 mg for haloperidol. The mean±SD daily doses that were actually achieved by the end of period 2 were 526.6±140.3 mg for clozapine, 30.4± 6.6 mg for olanzapine, 11.6±3.2 mg for risperidone, and 25.7±5.7 mg for haloperidol. Dosage changes during period 2 were requested by blinded psychiatrists on the basis of treatment response as measured by the PANSS and were tempered by clinical observation for adverse effects.

Concomitant medications that were permitted included benztropine, propranolol, lorazepam, diphenhydramine hydrochloride, and chloral hydrate. All patients who had been assigned to receive haloperidol received 2 mg of prophylactic benztropine twice daily. Patients who had been randomly assigned to receive risperidone, olanzapine, or clozapine received matching benztropine placebo. Treating physicians were permitted to prescribe additional benztropine, which resulted in the substitution of actual benztropine for placebo, up to a maximum of 6 mg a day. No other adjunctive psychotropics—for example, mood stabilizers or antidepressants—were allowed.

Blinded raters performed all the clinical assessments. The PANSS was the principal measure of efficacy and was administered every week for the first four weeks and then every other week. The interrater reliability, estimated by intraclass correlation coefficients, for the PANSS total score for paired ratings of the four sites ranged from .93 to .98. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the hostility item ranged from .86 to .88. In addition to the PANSS, we administered the Nurses Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (NOSIE) (16,17) and the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) (18).

We tested the hypothesis that clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol would have different effects on hostility; that clozapine's effect would be superior to those of the other drugs; and that this superiority would persist after general antipsychotic effect or sedation had been accounted for. The hostility item from the PANSS was adopted as the primary outcome measure. This item is scored on a scale ranging from 1, indicating no hostility, to 7, indicating extreme hostility that includes marked anger resulting in extreme uncooperativeness that precludes other interactions or in one or more episodes of physical assault against others. A score of 3 is assigned when the patient presents a guarded or even openly distrustful attitude but his or her thoughts, interactions, and behavior are minimally affected. Covariates included the sum of the PANSS measures of positive psychotic symptoms (excluding excitement and hostility) and unusual thought content, and the NOSIE measure of sedation.

Hierarchical linear model analysis was adopted as the principal statistical analysis. Repeated assessments of hostility over time—that is, the severity of hostility as assessed by the PANSS—was the dependent variable. The two independent variables were treatment group (the between-subject factor) and time (the within-subject factor). Time was expressed as the number of weeks since baseline. The interaction between treatment group and time was included in the model. To correct for potential confounding variables, change in certain positive symptoms (the sum of the items on delusions, suspiciousness or feelings of persecution, grandiosity, unusual thought content, conceptual disorganization, and hallucinatory behavior from the PANSS) and sedation (the item "is slow moving and sluggish" from the NOSIE) were introduced, in separate analyses, as covariates in the hierarchical linear model.

Additional analyses were conducted by using as covariates the anxiety and depression factor from the PANSS, the excitement item from the PANSS, akathisia as measured by the ESRS, ethnicity, and change in dosage over time. The hierarchical linear model compensates for baseline differences between groups. To account for intersite variations in severity at baseline and change over time, an unstructured covariance matrix with heterogeneity among participating centers was specified in the hierarchical linear model. The purpose of this provision was to ensure that changes in clinical variables over time were not confounded by intersite variability.

A nonparametric survival analysis with Kaplan-Meier estimates was used to test whether the four treatment groups differed in time to attrition—or survival—in the study. Use of adjunctive medications was investigated by using chi square analysis for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Results

Data were collected between mid-1996 and the start of 2000. A total of 167 patients were randomly assigned to treatment with one of the four antipsychotics; ten of these patients left the study before they had received any medication. Of the 157 patients who entered the medication phase of the study, 133 (85 percent) were men, and 24 (15 percent) were women; 135 patients (86 percent) had a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia, and 22 (14 percent) had a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. The mean±SD age of the patients was 40.8±9.2 years, duration of illness was 19.5±8.4 years, and number of hospitalizations was 10.5±8.3. Eighty-seven patients (55 percent) were African American, 48 (31 percent) were white, 18 (12 percent) were Hispanic, and four (3 percent) were from other ethnic groups. The differences between treatment groups in baseline scores on the PANSS hostility item or in any demographic variable were not significant.

Ninety-one patients (58 percent) completed the 14-week study; 133 patients (85 percent) completed at least four weeks. The differences in attrition rates among treatment groups were not significant. The most frequent reason for premature discontinuation was withdrawal of consent, which was the case for 22 patients—five patients in the clozapine group, four in the olanzapine group, eight in the risperidone group, and five in the haloperidol group. Clinical deterioration resulted in premature termination in the case of 14 patients—two in the clozapine group, four in the olanzapine group, two in the risperidone group, and six in the haloperidol group. Six patients were discharged and could not participate in the follow-up—three in the risperidone group and one in each of the other three treatment groups. Hematological problems and seizures led to discontinuation by seven patients. The remaining 17 premature discontinuations occurred for administrative reasons, intercurrent illnesses, and protocol violations.

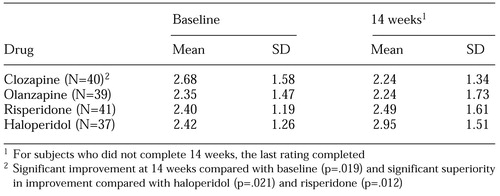

The patients' mean±SD scores on the hostility item of the PANSS are listed in Table 1. Statistical testing of this item using the hierarchical linear model included all data available at all time points and was controlled for general antipsychotic effect, sedation, and study site. The baseline score was higher in the clozapine group than in the other groups, but the difference was not significant. Moreover, the hierarchical linear model controls for such heterogeneity.

The four antipsychotics differed in their effect on the hostility item of the PANSS (F=2.8, df=3, 989, p=.038). The effect sizes were .25 for clozapine, .06 for olanzapine, .05 (indicating deterioration) for risperidone, and .30 (also indicating deterioration) for haloperidol. The reduction in hostility over time was significant for clozapine only (t=2.3, df=989, p=.019). This finding was maintained when only the data from period 1 were used (t=2.85, df=664, p=.005). Post hoc analysis indicated that clozapine had a significantly greater specific antiaggressive effect than haloperidol (t=2.3, df=989, p=.021) or risperidone (t=2.53, df=989, p=.012) but not olanzapine. Neither risperidone nor olanzapine showed superiority over haloperidol.

These treatment effects were not altered by introducing as covariates the PANSS items that reflect delusional thinking, a formal thought disorder, or hallucinations or the sedation item from the NOSIE. The analysis was repeated to assess the possible confounding effects of the anxiety and depression factor of the PANSS, the PANSS excitement item, akathisia as measured by the ESRS, ethnicity, and changes in dosage over time. When these variables were introduced as covariates, the findings were essentially unchanged.

Agitation and insomnia were treated as needed with lorazepam, chloral hydrate, or diphenhydramine. Differences between treatment groups in the use of these agents were not significant. Only two patients in the risperidone group and one in the haloperidol group used propranolol.

Discussion

Clozapine appeared to have a specific antiaggressive effect that was independent of general antipsychotic effect and independent of sedation. This observation was not made in the case of olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol. In contrast with the statistically significant superiority of clozapine over haloperidol or risperidone in improving scores on the hostility item of the PANSS, clozapine was not shown to be superior to olanzapine. This finding may be consistent with the structural similarities between clozapine and olanzapine, although observable differences between these two agents may have been limited by the low baseline rates of hostility and the relatively small sample.

An important limitation of this study is that the patients were not selected specifically because they had a history of aggressive and hostile behavior. Overt hostility was demonstrated largely by verbal expression of resentment rather than by physical assault. Although the extent to which our results are generalizable to populations of seriously assaultive patients is not clear, we believe that they probably are generalizable, because other researchers have noted parallel reductions in verbal and physical assaultiveness during clozapine treatment (19). Another limitation is that we used only one outcome measure for a complex behavior.

The effect of risperidone on hostility in our study differed from that reported by Czobor and colleagues (11), whose analysis was based on a large multicenter trial that had the primary goal of comparing the general antipsychotic efficacy of risperidone with that of haloperidol. Significant methodological differences exist between the study by Czobor and associates and our study. In the Czobor study, the risperidone group consisted of four subgroups that were differentiated by daily dose (2, 6, 10, or 16 mg). Moreover, the patients in that study were not defined as being treatment resistant. It is possible that the antiaggressive effect of risperidone varies with dosage and degree of treatment refractoriness.

Ideally, studies of putative antiaggressive agents should be conducted with subjects who have been selected specifically because of their aggressive behavior and use a double-blind design and random assignment to treatments. Such an approach is operationally difficult because of the relative rarity of aggressive events and the subsequent need for a large sample and long baseline and trial periods, selection or consent bias, and practical barriers such as the need for a specialized inpatient unit designed to manage this challenging patient population (15).

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the antihostility effects of four widely used antipsychotics—clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol—in a randomized clinical trial. The pattern of the results indicates that clozapine has a relative advantage over the other antipsychotics as an agent that reduces hostility. This antihostility effect appears to be independent of the drug's effects on other symptoms of psychosis and independent of sedation.

Acknowledgments

The principal support for this study was provided by grant R10-MH-53550 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Additional support was provided by grant MH-33127 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the University of North Carolina Mental Health and Neuroscience Clinical Research Center, and by the Foundation of Hope in Raleigh, North Carolina. The authors thank Janssen Pharmaceutica, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, and Merck and Co., Inc., for their donations of medications. Eli Lilly and Company contributed supplemental funding. Linda Kline, R.N., M.S., was the chief coordinator of the project.

Dr. Citrome, Dr. Volavka, Dr. Czobor, and Mr. Cooper are with the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research in Orangeburg, New York, and New York University in New York City. Mr. Cooper is also with the Psychiatric Institute of Columbia University in New York. Dr. Sheitman and Dr. Chakos are with the University of North Carolina in Charlotte and Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh. Dr. Lindenmayer is affiliated with New York University and the Manhattan Psychiatric Center. Dr. McEvoy is with Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, and John Umstead Hospital in Butner. Dr. Lieberman is with the University of North Carolina. Send correspondence to Dr. Citrome at the Nathan Kline Institute, 140 Old Orangeburg Road, Orangeburg, New York 10962 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, held May 5-10, 2001, in New Orleans.

|

Table 1. Scores at baseline and at 14 weeks on the hostility item of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale among 157 inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who were taking clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol

1. Wilson WH, Claussen AM:18-month outcome of clozapine treatment for 100 patients in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services 46:386-389, 1995Google Scholar

2. Ratey JJ, Leveroni C, Kilmer D, et al: The effects of clozapine on severely aggressive psychiatric inpatients in a state hospital. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:219-223, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

3. Chiles JA, Davidson P, McBride D: Effects of clozapine on use of seclusion and restraint at a state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:269-271, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Mallya AR, Roos PD, Roebuck-Colgan K: Restraint, seclusion, and clozapine. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 53:395-397, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

5. Spivak B, Mester R, Wittenberg N, et al: Reduction of aggressiveness and impulsiveness during clozapine treatment in chronic neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenic patients. Clinical Neuropharmacology 20:442-446, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Maier GJ: The impact of clozapine on 25 forensic patients. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 20:297-307, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

7. Ebrahim GM, Gibler B, Gacono CB, et al: Patient response to clozapine in a forensic psychiatric hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:271-273, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Volavka J, Zito JM, Vitrai J, et al: Clozapine effects on hostility and aggression in schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 13:287-289, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Buckley P, Bartell J, Donenwirth MA, et al: Violence and schizophrenia: clozapine as a specific antiaggressive agent. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 23:607-611, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kay SR, Opler LA, Lindenmayer JP: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): rationale and standardisation. British Journal of Psychiatry 155(suppl):59-65, 1989Google Scholar

11. Czobor P, Volavka J, Meibach RC: Effect of risperidone on hostility in schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 15:243-249, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Marder SR, Meibach RC: Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:825-835, 1994Link, Google Scholar

13. Buckley PF, Ibrahim ZY, Singer B, et al: Aggression and schizophrenia: efficacy of risperidone. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:173-181, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

14. Beck NC, Greenfield SR, Gotham H, et al: Risperidone in the management of violent, treatment-resistant schizophrenics hospitalized in a maximum security forensic facility. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:461-468, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

15. Volavka J, Citrome L: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of the persistently aggressive psychotic patient: methodological concerns. Schizophrenia Research 35: S23-S33, 1999Google Scholar

16. Honigfeld G, Gillis RD, Klett CJ: NOSIE-30: a treatment-sensitive ward behavior scale. Psychological Reports 19:180, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Honigfeld G: NOSIE-30: history and current status of its use in pharmacopsychiatric research. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry 7:238, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Chouinard G, Ross-Chouinard A, Annable L, et al: Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 7:233, 1980Google Scholar

19. Rabinowitz J, Avnon M, Rosenberg V: Effect of clozapine on physical and verbal aggression. Schizophrenia Research 22:249-255, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar