Risks for Individuals With Schizophrenia Who Are Living in the Community

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the incidence and predictors of police contact, criminal charges, and victimization among noninstitutionalized individuals with schizophrenia living in the community. METHODS: A total of 172 individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were recruited from community-based programs in urban Los Angeles between 1989 and 1991 and were monitored for three years. At baseline, all participants were housed and did not have co-occurring substance use disorders. Face-to-face interviews were conducted every six months. RESULTS: Eighty-three individuals (48 percent) had contact with the police during the study period. A small percentage of the contacts involved aggressive behavior against property or persons. Being younger, having had more address changes at baseline, and having a history of arrest and assault were significant predictors of police contact. Thirty-seven individuals (22 percent) reported that charges had been filed against them. Poorer social functioning, more address changes, fewer days of taking medication at baseline, and a history of arrest and assault were significant predictors of criminal charges. Sixty-five participants (38 percent of the sample) reported having been the victim of a crime during the three years, 91 percent of which was violent. Having more severe clinical symptoms and more substance use at baseline were significant predictors of victimization. CONCLUSIONS: Individuals in this sample were at least 14 times more likely to be victims of a violent crime than to be arrested for one. In general, the risk associated with being in the community was higher than the risk these individuals posed to the community

One outcome of the deinstitutionalization of individuals who have schizophrenia is that these persons now spend most of their lives in the community (1). This has resulted in new challenges for consumers, family members, service providers, and the general community. One aspect of this challenge is community risk, which can be defined as risk both to and from the community (2). One set of risks to the community has to do with criminal activity and dangerousness of individuals with schizophrenia as a result of the seriousness of their mental illness (3,4,5). On the other hand, individuals who have schizophrenia have been said to represent a potentially vulnerable population that is at risk of significant victimization in the community (2,6).

In addition, most recent attempts to measure the quality of life or the community adjustment of individuals with schizophrenia have specified a construct of community risk that refers to public welfare and safety issues, such as health status, contact with the police, crime, and victimization (2,6,7). The purpose of this study was to examine the incidence and individual predictors of three kinds of community risk—police contact, criminal charges, and victimization—over a three-year period in a sample of noninstitutionalized individuals with schizophrenia who were living in the community.

Background

Police contact

Studies have shown that the police play a pivotal role by acting as gatekeepers to the criminal justice and mental health systems (8,9,10,11,12,13). Robertson and colleagues (14) studied factors that influenced entrance of mentally ill individuals into the criminal justice or mental health system and the circumstances of arrest of those who entered the criminal justice system. These authors found that arrest was associated with violent behavior at the time of the incident; that 54 percent of the individuals with a mental illness were charged with a nonnotifiable offense (disturbing the peace—for example, vagrancy or begging), compared with 32 percent of the general population; and that 57 percent of cases of notifiable offenses were discontinued or dismissed on the basis of the person's being mentally ill. Furthermore, Robertson and colleagues reported that males and black persons were more likely to be arrested and that the severity of symptoms appeared to play a role in arrest and detention.

Only two studies have examined police contact among individuals with severe mental illness in the community. Clark and colleagues (15) found that 83 percent of a sample of 169 individuals with dual diagnoses had contact with the broadly defined legal system, and 44 percent had been arrested at least once in a three-year period. Substance use and an unstable housing situation were associated with a greater likelihood of arrest.

Wolff and colleagues (16) evaluated clients in an assertive community treatment program over a one-year period and found that 31 percent had no contact with the police, 41 percent had at least one police contact but were not arrested, and 28 percent were arrested or incarcerated. The police classified most of the contacts with clients as "disturbances" whether the clients were suspects or victims. Victimization was a common reason for police contact, accounting for 45 percent of the contacts with police. Wolff and colleagues found that young, African-American males were more likely than others to be arrested.

The combined results of these two studies suggest that substance use, housing instability, race, and younger age are associated with more police contact. However, neither of the studies was conducted in an urban setting among a diagnostically homogeneous group of individuals who had schizophrenia, the definitions of police contact were very generic, and neither study used a range of individual predictors of police contact that reflected current and past clinical and functional status.

Arrest and crime

Arrest rates are generally higher among individuals who have schizophrenia than in community samples of persons who do not have mental illness (4,12,17,18). People with schizophrenia may be more likely to be arrested because they behave oddly as a result of their illness (14); also, being younger and having a history of arrest may predict future arrest (18).

Although arrest rates are higher among persons who have schizophrenia, rates of criminal behavior—based on convictions—are the same for individuals with schizophrenia as in community samples (19,20,21). However, conviction rates can overestimate crime—because people with schizophrenia are easier to convict—or can underestimate criminal behavior if these individuals are diverted to the mental health system before they are convicted (22). Alcohol and drug use among individuals with schizophrenia has been associated with a higher crime rate in this group (33,21,22,23,24).

Whether persons who have schizophrenia are more violent than persons who do not have a mental illness is not entirely clear from the literature. Various studies have found that rates of violent crime among persons with schizophrenia are higher than or similar to those among persons who do not have a mental illness. For example, a recent study in Denmark showed that individuals who were hospitalized for schizophrenia had higher rates of arrest for violent crime than those who had never been hospitalized (5). However, the results of two earlier European studies do not support this finding (21,23).

Studies in the United States have shown that violent behavior and crime were related to the presence of psychotic symptoms among the mentally ill (4), to the co-occurrence of substance abuse with schizophrenia (3,23), and possibly to a decompensated clinical state among persons with mental illness (3). Most recent U.S. studies have found that the stereotype of the dangerousness of persons with serious mental illness is unfounded (3,4,25). As Link and colleagues (4) stated, "If the patient is not having a psychotic episode, or if the psychiatric problems do not involve psychotic symptoms, then he or she is no more likely than the average person to be involved in violent/illegal behavior."

Many studies of the criminal activity of persons who have schizophrenia have focused on individuals with dual diagnoses, on homeless persons, or on persons who had already been arrested or convicted of a crime. These groups must be considered to be high-risk samples. However, no prospective data are available on the incidence of crime, types of criminal activity, or predictors of criminal charges in samples that would be considered to be at lower risk as a result of being housed in the community and not having a diagnosis of a co-occurring substance use disorder.

Victimization

Lam and Rosenheck (26) examined the prevalence of victimization among homeless persons with mental illnesses and found that 44 percent had been victims of at least one crime in the previous two months; crimes included robbery, theft, use of a weapon, and physical or sexual assault. Lehman and colleagues (27) found that 34 percent of a residential sample had been victims of robbery or assault within a one-year period.

Chuang and colleagues (19) found that patients with schizophrenia were three times more likely to be victims of violent crime than persons who did not have a mental illness. Several predictors of victimization among homeless persons were identified: severity of psychotic symptoms, alcohol use, criminal history, history of victimization, sex, race, employment status, social environment, and economic status (26). These authors also found that a significant proportion of victimization was not reported to the police.

Hiday and colleagues (28) studied a sample of individuals with severe mental illness who were involuntarily hospitalized and then ordered to participate in outpatient treatment. These authors found that 27 percent of their sample had been victimized in the previous four months and that substance use and transient living conditions were associated with elevated rates of victimization. They also found that the rate of violent criminal victimization in their sample was two and a half times greater than in the general population.

In general, these studies of victimization among individuals with serious mental illness have focused on diagnostically mixed samples that are at high risk as a result of being homeless or seriously disabled because of their illness.

Study questions

The studies we have discussed on community risk among persons who have severe mental illness reveal several trends. First, most of the studies used samples of individuals who were at high risk because of homelessness, dual diagnosis, or compromised clinical status. Thus these studies provide only a partial picture of community risk for the total population of individuals with schizophrenia who reside in the community. Second, few studies examined police contact or victimization, and those that did used samples with a mix of psychiatric diagnoses. Third, only one study used a prospective design. The absence of prospective designs limits the kinds of predictors of community risk that can be used as well as the significance of the models that are developed to predict community risk. Fourth, few studies used a full range of clinical, functional, and demographic variables as predictors of community risk.

Our study addressed a number of these issues by examining, over a three-year period, a sample of individuals with diagnoses of schizophrenia who were living in an urban environment. Compared with samples used in previous studies, our sample must be considered a lower-risk sample because of an absence of comorbid substance abuse or dependence at the time of study entry and because the participants were housed in the community at baseline. As such, this was a sample of individuals for whom community risk would not generally be considered a focal issue. Second, because of the low occurrence of two other major risk factors—homelessness and substance use—this sample provides a more accurate representation of the contribution of schizophrenia to community risk.

We addressed two sets of questions. First, what were the rates and types of police contact, criminal charges, and victimization over a three-year period in this sample of individuals with schizophrenia? Second, considering clinical status, current psychosocial functioning, demographic variables, and functional history, what were the predictors of police contact, criminal charges, and victimization over the three years?

Methods

Design

This was a follow-along study of 172 individuals who had diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. All of the participants had been admitted to one of three community-based programs in urban Los Angeles between 1989 and 1991 and were monitored over a three-year period (29). The three programs have been described in detail elsewhere (29,30,31). Nearly all of the participants had received treatment in the publicly funded mental health system and were receiving public assistance. To be eligible for the study, in addition to having a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, participants had to have lived in Los Angeles for at least three months and to be 18 to 60 years of age, and they could not have a diagnosis of mental retardation or organic brain syndrome or a current diagnosis of substance dependence. All subjects consented to participate in the study under procedures that had received approval from the institutional review board of the University of California.

Measures of psychosocial functioning were administered during face-to-face interviews at baseline and every six months during the three-year study period. A life history interview was conducted at baseline. Diagnoses were established through a two-step process. First, an initial diagnostic screening for schizophrenia based on chart and interview data was conducted by an admitting clinician at the program sites. All participants who passed the first screening subsequently received diagnoses in a face-to-face interview by a licensed doctorate-level clinician trained in the use of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) (32). Structured interview data and clinical records were used to determine the SADS diagnosis, which included the assessment for current substance dependence. Interviewer training and reliability protocols have been described in detail elsewhere (33).

During the first six months of the study, any participant who dropped out was replaced and was excluded from the analyses. The study sample was recruited over an 18-month period.

Measures

Functional measures. The Community Adjustment Form (CAF) (34) is a semistructured interview in which the subject reports objective behaviors or events that have occurred during a six-month period. This measure contains 17 domains of psychosocial functioning and community adjustment and is designed to minimize the subjective ratings of interviewers. After extensive training of the interviewers, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) obtained from 22 interviews indicated excellent interrater reliability (range, .75 to .98).

Two additional functional outcome measures were used: the Role Functioning Scale (RFS) (35,36) and the Strauss and Carpenter Outcome Scale (SCOS) (37). The SCOS has been used widely in schizophrenia research, and the RFS was identified as the scale of choice for this population by Green and Gracely (38). Both scales use single items with multiple descriptive anchors to assess a functional domain. The scales each assess outcome in four distinct domains. The variables used in this study were the work item from the SCOS and the independent living, family functioning, and social functioning items from the RFS. The scale ratings were derived from the CAF according to procedures that have been outlined elsewhere (39). Interrater reliability was established on the basis of the ICCs during intensive rater training and during booster rating assessments throughout the study. The ICCs on the four outcome items ranged from .75 to .98 (mean=.89).

Clinical measures. The measure of symptoms was the overall score on the 22-item version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (40,41). After intensive rater training, ICCs on the items ranged from .74 to .98 (mean=.92). The intrapsychic-deficits measure was the intrapsychic-foundations subscale of the Quality of Life Scale (42). ICCs on the items ranged from .85 to .97 (mean=.91).

Life history measure. We used the Demographic Interview Form (34), a life history interview, at baseline only. It captures social demographic data and functional history data in several psychosocial areas and targets an individual's life history up to the point of study entry.

Study variables

Predictors. Four domains of predictors were used: baseline functional status, baseline clinical status, demographic variables, and history of problems. The demographic variables were sex, age, and race. The clinical-status variables were number of days of psychiatric hospitalization in the six months before study entry, number of days of taking psychiatric medications in the six months before study entry, overall severity of symptoms at study entry, and intrapsychic deficits at study entry. Psychosocial functioning included baseline housing stability, substance use, and three items from the RFS that measured family relations, social skills, independent living skills, and the work item from the SCOS. Finally, the four problem-history variables were lifetime history of suicide attempt, arrest, assault, and substance use before study entry.

Criterion variables. The dependent variables had three domains: police contact, criminal charges, and victimization. The police-contact data consisted of the number of police contacts in the previous six months that were not related to being victimized and the nature of each contact. The criminal-charge data consisted of the number of charges in the previous six months and the nature of each charge. The victimization data consisted of the number of times the subject was victimized in the previous six months and the nature of the victimization. The nature of the community-risk events—police contact, criminal charges, and victimization—were coded into categories from written interview data by three research assistants using a consensus method. For some variables these data were collapsed over the three-year study period to yield data on whether an individual had had contact with the police during the three years, whether criminal charges had been filed against the individual during the period, and whether the individual had been victimized during the period.

Studies on the reliability and validity of self-report data on criminal and violent behavior among individuals with serious mental illness have been published (3,4). These studies found that self-reports of criminal behavior provided higher incidence rates than official arrest records or information from collateral informants.

Data analysis

To determine predictors of the three dichotomous variables—police contact, criminal charges, and victimization—we performed logistic regression. A total of 17 predictor variables were grouped into four conceptual categories: demographic variables, baseline clinical status, baseline psychosocial functioning, and history of problems.

On the basis of this conceptual framework, we used the same two-step procedure for each dependent variable. In step one, we performed four separate logistic regression analyses by using each conceptual group of predictor variables forced into the equation as a block. This approach avoided the inflation of the type I error rate associated with stepwise entry procedures. Only significant variables (p<.05) from each block or conceptual category in the first step were retained for the second step. In the second step, we combined the significant variables from the first step and entered them all as a block to derive the final models for predicting each dependent variable.

Results

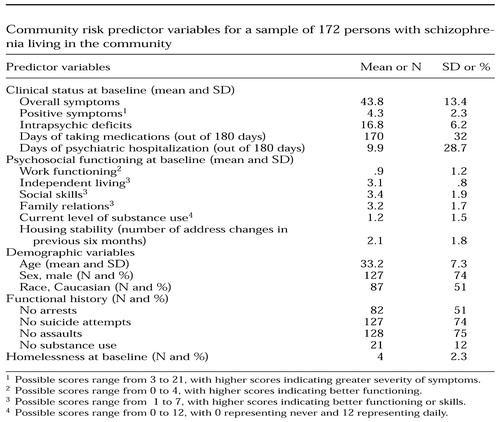

Sample

Ninety-eight percent of the sample were housed at baseline; in aggregate, the sample had symptoms in the moderate range, which is similar to other outpatient samples of individuals with schizophrenia, and had low levels of current substance use. As shown in Table 1, less than 3 percent of the sample received a score of 11 or higher on the positive-symptom subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, which reflects the severity of psychotic symptoms (possible scores range from 3 to 21, with higher scores reflecting greater severity). This finding suggests that the vast majority of this sample was not experiencing severe psychotic symptoms at baseline.

During their adult life until study entry, 78 subjects (49 percent of the sample) had been arrested, 44 (25 percent) had committed assault, and 45 (26 percent) had attempted suicide. A total of 143 individuals (83 percent of the sample) had been taking antipsychotic medication every day during the six months before study entry, and the sample generally maintained this high level of medication use throughout the study period. Most of the sample was male (127 individuals, or 74 percent); the number of subjects from racial minorities—50 African American (29 percent of the sample), 27 Hispanic (16 percent), and 8 (4 percent) other—was almost equal to the number of nonminority Caucasians (87 individuals, or 51 percent).

At 12 and 18 months, 88 percent of the original sample had been retained. The retention rate dropped to 83 percent at 24 months, 80 percent at 30 months, and 72 percent at 36 months. We compared the 123 individuals who completed the study at 36 months with the 49 who dropped out of the study in sex, race, prognosis, age, duration of illness, severity of symptoms at baseline, baseline role functioning, and baseline substance use. None of the differences were statistically significant.

Descriptive data

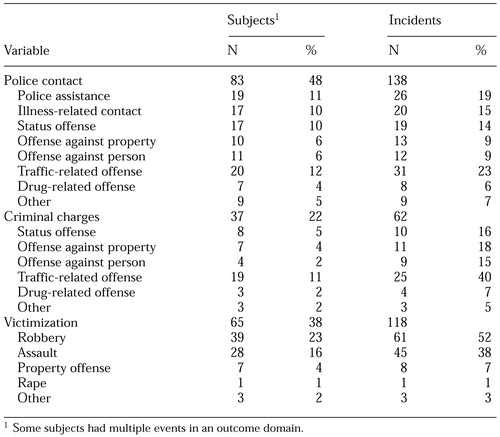

Police contact. The descriptive data on the community risk variables during the three-year study period are shown in Table 2. Eighty-three participants (48 percent of the sample) had contact with the police during the three years, for a total of 138 separate contacts. The vast majority of the contacts (120 incidents, or 87 percent) were initiated by someone other than the study participant, such as the police or other individuals. Twenty-five (18 percent) of the contacts involved aggressive behavior against property or persons. The single largest category of contacts involved traffic-related offenses, such as jaywalking and traffic violations; most other contacts were related to status offenses, such as vagrancy, or illness or were general police-assistance calls.

Criminal charges. Thirty-seven individuals (22 percent of the sample) reported that charges had been filed against them during the three years, for a total of 62 separate charges. Only 20 of the charges (32 percent) were for behavior against property or persons; most of the charges were associated with status or traffic-related offenses. Only 6.4 percent of the sample reported having been charged for behavior against persons or property during the three-year period; 2.3 percent were charged for violent behavior against another person.

Victimization. Sixty-five individuals (38 percent of the sample) reported having been the victim of a crime during the three years. A total of 118 separate victimization incidents were reported, 70 (59 percent) of which had not been reported to the police; 107 (91 percent) of the victimization incidents involved robbery, rape, or assault, which are considered violent crimes. Fifty-nine subjects (34 percent of the sample) reported having been the victim of a violent crime during the three-year period.

Annual incidence rates. Annual incidence rates can be useful for comparison with other population data. In this study we provided an upper and lower value for each annual incidence rate. The lower value was the three-year rate for that category divided by three. The upper value was the average of the three separate yearly rates. It must be emphasized that because this was not a random sample, these incidence rates are sample estimates only. The annual incidence of police contact was 16 to 19.3 percent, of police charges was 7.3 to 8.7 percent, and for victimization was 12.7 to 17.7 percent. All other annual rates presented below reflect the same procedure.

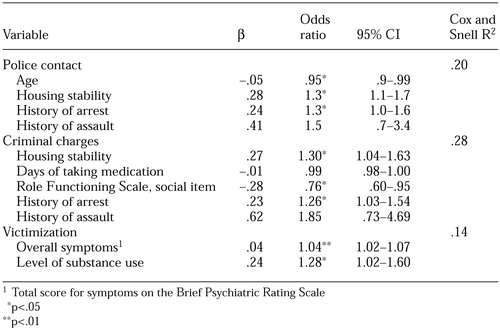

Logistic regression

The results of the logistic regression analyses are shown in Table 3. All of the equations were significant (p<.001).

Police contact. Younger age, more address changes at baseline, and a history of arrest and assault were associated with a higher probability of police contact. The Wald test statistic for history of assaults was not significant when the other predictors were in the equation. The results for predicting the probability of police contact initiated by individuals other than the study participant, which reflects the most serious risk to the community, are shown in Table 3.

Criminal charges filed. Poorer social functioning, more address changes, fewer days of taking medication, and a history of arrests and assaults were associated with a higher probability of criminal charges being filed against an individual during the three-year study period. The effect of medication use was significant at p<.06. As with police contact, history of assault was not a significant predictor when the other variables were in the equation.

Victimization. A greater severity of clinical symptoms and more substance use at baseline were associated with a higher probability of victimization during the three years. Severity of symptoms was a stronger predictor than substance abuse.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the self-reported rates of police contact, criminal charges, and victimization over a three-year period among individuals with diagnoses of schizophrenia who were living in a major urban community in the United States. At baseline these individuals were housed in their community, did not have co-occurring substance use disorders, and were in a nonacute phase of their disorder. With these baseline characteristics, this sample could be considered to be more stable and at a lower risk than samples in most previous studies of community risk among individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. Because this was a prospective study, we were also able to use a comprehensive set of baseline variables to predict future community risk.

In examining these data, it is important to distinguish risk to the community—represented by police contact and criminal charges—and risk from the community—represented by victimization. Police contact and criminal charges are costly (15) and can threaten the well-being of the general community (4). High rates of police contact can also be seen as an indication that the police are serving a mental health function in the community (13).

We found high rates of police contact in our sample: nearly 50 percent of the participants had police contact at least once during the three years, and the annual rate was 16 percent to 19.3 percent. Eighty-four percent of the police contact was initiated by someone other than the participant. A minority of the contacts were related to behavior against persons or property.

It is difficult to compare the data from this sample with national population data because of reporting differences in the databases. However, the annual rate of face-to-face contact with the police for somewhat comparable events was about 7 to 8 percent of the U.S. population in 1996, one of the first years that national data were gathered (43). Fifty-four percent of the police contact in the national sample was initiated by someone other than the subject. Compared with a national public sample, individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community have more than twice as much contact with the police, and far more of this contact is initiated by someone else, including the police. It is not clear why the police have this rate of involvement, but the kind of contact is most likely to be related to behavior that is not violent or threatening to property.

Only one previous study of persons with serious mental illness who were participating in community-based treatment—in Madison, Wisconsin—produced comparable data on police contact. In that study, 38 percent of the sample had police contact unrelated to victimization in a 12-month period (16). This rate is considerably higher than the rate in our sample. It is possible that the community context is important here: Madison is a much smaller city and has well-developed assertive outreach programs that strive to keep individuals with schizophrenia in the community. These conditions could increase the likelihood of police interaction with persons who have mental illness.

The predictors of police contact in our study were younger age, more address changes, and a history of arrest or assault. This pattern suggests that younger, more transient individuals with histories of assault and previous contact with the police are more likely to have contact with the police in the future. It is difficult to compare these findings with those from previous studies for several reasons—for example, one study did not distinguish between victim and nonvictim police contact—but having an unstable housing situation and being younger were consistent predictors across studies and samples. Substance abuse and a history of arrest or assault were also predictive of police contact.

Twenty-two percent of our sample had charges filed against them during the three-year study period. This finding suggests that fewer than half of the police contacts resulted in charges being filed. The yearly arrest rate in our sample was 7.2 to 8.7 percent. The arrest rate in Los Angeles in 1993 was 5.6 percent of the adult population (44). Fewer than 30 percent of the charges involved behavior against persons or property; the vast majority of charges involved status offenses or traffic-related offenses. Only 2.3 percent of the total sample reported having been charged for behavior against a person during the three years; the yearly rate was .8 to .93 percent. The annual arrest rate for comparable crimes in Los Angeles in 1993 was 1.3 percent (44).

Two previous studies of persons with severe mental illness found higher arrest rates than ours, although these studies are not directly comparable with ours. Wolf and associates (16) reported a rate of 28 percent for a 12-month period, but in their study arrests and incarcerations were combined. Clark and colleagues (15) reported a rate of 44 percent for a three-year period, but their sample had dual diagnoses of a major mental disorder and a substance use disorder. The arrest rate in our sample was similar to that reported by Harry and Steadman (18), who used a diagnostically heterogeneous group of inpatients and outpatients in a rural area of Missouri and included arrest data from 1975 and 1983.

In our study, poorer social functioning, more address changes, fewer days of taking medication, and a history of arrests or assaults were predictive of a criminal charge. This finding suggests that compared with individuals who have had police contact only, those who have been charged by the police are more seriously debilitated and less compliant with treatment, although both groups have unstable living situations and have histories of acting out and police contact.

Taken together, the first two indicators of risk to the community—police contact and criminal charges—suggest that the police have extensive contact with persons in the community who have schizophrenia but that most of this police involvement (70 percent) concerns behavior such as traffic offenses, jaywalking, and police-assistance calls, not offenses against property or persons. Less than half of the police contact resulted in charges being filed. The arrest rate was about 45 percent higher than that among the general public, but the arrest rate for violent crimes was almost 40 percent lower than among the general public.

As for the predictors of police involvement, more serious involvement—for example, criminal charges as opposed to mere contact with the police—was associated with more compromised functioning. In fact, the police had the most intensive interaction with individuals who had the greatest mental health needs. Thus the challenges and risks that these individuals pose to the police increase as the police interact more intensively with more debilitated individuals with schizophrenia. Without adequate training for the police officers who interact with persons with serious mental illness, there is also a greater risk to the ill individuals themselves. This elevated risk suggests the importance of specialized police training in serious mental illness and the need for more community-based real-time crisis assistance to police officers from specialized mental health care providers.

When these results are combined with the results of previous studies of seriously mentally ill persons in the community, it is clear that a great deal of the risk that individuals who have schizophrenia pose to the community comes from conditions that coexist with schizophrenia, such as substance use and homelessness. Nonetheless, younger age, fewer days of taking medications, a more unstable housing situation, poorer social functioning, and a history of police involvement were associated with a greater likelihood of police contact or arrest. This information should guide service providers in their assessments and planning for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community.

Thirty-eight percent of our sample reported having been the victim of a crime during the study period. This represents an annual rate of 12.7 to 17.7 percent. The rate in Los Angeles was 7.7 percent in 1993 (44). In our sample, 91 percent of the victimization was of a violent nature, which corresponds with an annual rate of violent victimization of 11.3 to 14.5 percent. The annual rate of violent victimization in Los Angeles in 1998 was 6.5 percent of the population (43).

In our sample, 59 percent of victimization was not reported to the police, which is comparable to the rate of about 58 percent in the general population (43). Individuals who have schizophrenia and who are living in the community have a victimization rate 65 to 130 percent higher than that of the general public. The rate of violent victimization was 75 to 120 percent higher among individuals with schizophrenia than among the general public. Some previous studies found considerably higher rates of victimization, but those studies targeted individuals who were homeless, had dual diagnoses, or were severely ill (26,28).

As for the predictors of victimization, being more symptomatic and having greater substance use at baseline were related to higher rates of victimization, and the severity of symptoms was the strongest predictor. This finding suggests that the most ill and vulnerable persons with schizophrenia are the most likely to be victimized. Substance use could compound their vulnerability by making them less able to fend for themselves and could expose them to exploitation by others. Given that six out of ten crimes are not reported to the police, it is possible that these individuals do not believe that the police will handle their situations adequately; however, this rate is nearly identical to the rate of nonreporting among the general public. Thus we have a highly vulnerable group that is victimized at high rates, and they generally do not seek protection from the police or the justice system.

In considering the results on community risk as a whole, it is apparent that there is substantial risk associated with schizophrenic individuals residing in the community. However, the overall risk is not due to the dangerous behavior of the ill individuals but rather to the high rates of contact that these individuals have with the police and to their high rates of victimization. The victimization of persons with schizophrenia is generally violent, involves the most vulnerable members of this group, and is usually not reported. Individuals in the community who have schizophrenia are at least 14 times more likely to be a victim of a violent crime than to be arrested for one. These individuals are more likely to be arrested than members of the general public, but such an arrest is less likely to be for a violent crime than is the case among the general public.

On the basis of these results, it is clear that for these individuals with schizophrenia the risk associated with being in the community was higher than the risk they posed to the community. This finding suggests a challenge to policy makers and service providers. Clearly, there must be greater interaction between the mental health sector and law-enforcement agencies. Police officers need education and training about mental illness as well as community-based crisis assistance from trained mental health providers when they deal with persons who have mental illnesses.

Three other aspects of these results deserve comment. The severity of symptoms at baseline was not related to subsequent police contact or to criminal charges being filed, which agrees with the findings of Monahan and colleagues (45). In this regard, some studies have found that threatening and violent behavior among mentally ill individuals was related to active psychotic symptoms (4,46). Because ours was a sample of individuals with nonacute illness and extremely low rates of active psychotic symptoms at baseline, it is understandable that the severity of symptoms at baseline was unrelated to risk to the community. In the study by Monahan and colleagues, only 17 percent of the sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and the baseline severity of psychotic symptoms was not reported. Thus the discrepancy in findings related to active psychotic symptoms across studies could be related to a low severity of symptoms at baseline or to the timing of the clinical assessments relative to that of the risk behavior.

Second, other studies showed that race was related to both police contact and criminal charges. Ours was a multiethnic sample in an ethnically diverse community with a multiethnic police force, which could have limited the influence of race on the rates of police contact. Third, several of the baseline predictors we used are dynamic and would be expected to change over the three-year study period—for example, housing stability and medication use. We did not examine the relationships between such changes and whether they influenced the occurrence of community risk incidents. Although such analyses could have provided information about causal relations, they would not have resulted in the same kind of prospective predictive models that we generated.

Our study had several limitations. First, we did not use a random sample. Thus we do not know how generalizable these results are to the overall population of persons with schizophrenia who are living in the community. However, as we have stated, our subjects were housed, did not have diagnoses of a co-occurring substance use disorder, and generally were compliant with medication. Second, Department of Justice or criminologic analyses were not taken into account when the data elements were designed. Thus the comparability of these data with other important public data sources is limited. Third, the use of arrest data from any source will underestimate the rates of violence in any population. Thus, although our study provided good estimates of arrest rates, this information clearly underestimates the rates of violent behavior in our sample. Finally, the findings are based on self-report data; however, as we have shown, this approach yields the highest single-source estimates of crime and violence in this population, and the rates are similar to those derived by triangulating multiple sources.

The results of this study have several implications for further research. Community risk should be measured by using data elements that are common to research on these topics. This approach would allow more adequate comparisons across databases and populations. Because random samples of individuals with schizophrenia are rare, the homogeneity of a study sample is not a problem as long as the sample is well described. It is then possible to compare community risk across samples that vary in important characteristics. Prospective studies are needed to examine changes in community risk as individuals make the transition out of homelessness and from substance abuse to recovery.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by research grant 43640 and independent scientist award 01628 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Brekke.

Dr. Brekke, Ms. Prindle, and Mr. Bae are affiliated with the School of Social Work at the University of Southern California, MC-0411, Los Angeles, California 90089-0411 ( [email protected] ). Dr. Long is with the department of educational psychology of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

|

Table 1. Community risk predictor variables for a sample of 172 persons with schizophrenia living in the community

|

Table 2. Community risk variables over a three-year period in a sample of 172 individuals with schizophrenia living in the community

|

Table 3. Predictors of community risk over a three-year period in a sample of 172 individuals with schizophrenia living in the community, as determined by using logistic regression analysis

1. Lehman AF: Public health policy, community services, and outcomes for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 21:221-231, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Attkisson C, Cook J, Karno M, et al: Clinical services research. Schizophrenia Bulletin 18:561-626, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393-401, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Link BG, Andrews H, Cullen FT: The violent and illegal behavior of mental patients reconsidered. American Sociological Review 57:275-292, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Brennan PA, Mednick SA, Hodgins S: Major mental disorders and criminal violence in a Danish birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:494-500, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF: Developing an outcomes-oriented approach for the treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:30-35, 1999Google Scholar

7. Rosenblatt A, Attkisson C: Assessing outcomes for sufferers of severe mental disorder: a conceptual framework and review. Evaluation and Program Planning 16:347-363, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Rogers A: Policing mental disorder: controversies, myths, and realities. Social Policy and Administration 24:226-236, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Shah SA: Mental disorder and the criminal justice system: some overarching issues. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 12:231-244, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bonovitz JC, Bonovitz JS: Diversion of the mentally ill into the criminal justice system: the police intervention perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:973-976, 1981Link, Google Scholar

11. Bittner E: Police discretion in emergency apprehension of mentally ill persons. Social Problems 14:278-292, 1967Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Teplin LA: The criminality of the mentally ill: a dangerous misconception. American Psychologist 39:794-803, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Teplin LA, Pruett NS: Police as streetcorner psychiatrist: managing the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 15:139-156, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Robertson G, Pearson R, Gibb R: The entry of mentally disordered people to the criminal justice system. British Journal of Psychiatry 169:172-180, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Clark RE, Ricketts SK, McHugo GJ: Legal system involvement and costs for persons in treatment for severe mental illness and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:641-647, 1999Link, Google Scholar

16. Wolff N, Diamond RJ, Helminiak TW: A new look at an old issue: people with mental illness and the law enforcement system. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:152-165, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. McFarland BH, Faulkner LR, Bloom JD, et al: Chronic mental illness and the criminal justice system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:718-723, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Harry B, Steadman HJ: Arrest rates of patients treated at a community mental health center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:862-866, 1988 (published erratum appears in Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1303, 1989)Google Scholar

19. Chuang HT, Williams R, Dalby JT: Criminal behaviour among schizophrenics. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 32:255-258, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Wessely S: The epidemiology of crime, violence, and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 32(suppl):8-11, 1997Google Scholar

21. Modestin J, Ammann R: Mental disorder and criminality: male schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:69-82, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Davis S: Assessing the criminalization of the mentally ill in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 37:532-538, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Tiihonen J, Isohanni M, Räsänen P, et al: Specific major mental disorders and criminality: a 26-year prospective study of the 1966 northern Finland birth cohort. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:840-845, 1997Link, Google Scholar

24. Holcomb WR, Ahr PR: Arrest rates among young adult psychiatric patients treated in inpatient and outpatient settings. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:52-57, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

25. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM: Does psychiatric disorder predict violent crime among released jail detainees? A six-year longitudinal study. American Psychologist 49:335-342, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Lam JA, Rosenheck R: The effect of victimization on clinical outcomes of homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:678-683, 1998Link, Google Scholar

27. Lehman AF, Ward NC, Linn LS: Chronic mental patients: the quality of life issue. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1271-1276, 1982Link, Google Scholar

28. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:62-68, 1999Link, Google Scholar

29. Brekke JS, Long J, Nesbitt N, et al: The impact of service characteristics on functional outcomes from community support programs for persons with schizophrenia: a growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:464-475, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Brekke JS, Ansel M, Long J, et al: Intensity and continuity of services and functional outcomes in the rehabilitation of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 50:248-256, 1999Link, Google Scholar

31. Brekke JS, Long J: Community-based psychosocial rehabilitation and prospective change in functional, clinical, and subjective experience variables in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, in pressGoogle Scholar

32. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:837-844, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Brekke JS, Levin S, Wolkon GH, et al: Psychosocial functioning and subjective experience in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 19:599-608, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Test MA, Knoedler WH, Allness DJ, et al: Long-term community care through an assertive continuous treatment team, in Schizophrenia Research: Advances in Neuropsychiatry and Psychopharmacology, vol 1. Edited by Carol A, Tamminga SCS. New York, Raven, 1991Google Scholar

35. McPheeters HL: Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: a perspective of two southern states. Community Mental Health Journal 20:44-55, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, et al: Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Mental Health Journal 29:119-131, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Strauss JS, Carpenter WTJ: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: I. characteristics of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 27:739-746, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Green RS, Gracely EJ: Selecting a rating scale for evaluating services to the chronically mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal 23:91-102, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Brekke JS: An examination of the relationships among three outcome scales in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:162-167, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychology Report 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Lukoff D, Liberman RP, Nuechterlein KH: Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:578-602, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WTJ: The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:388-398, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Criminal Victimization in the United States, 1998Google Scholar

44. Department of Justice: Crime in the United States, 1993Google Scholar

45. Monahan JS, Steadman HJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Developing a clinically useful actuarial tool for assessing violence risk. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:312-319, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Junginger J: Psychosis and violence: the case for a content analysis of psychotic experience. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:91-103, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar