Guardianship Applications for Elderly Patients: Why Do They Fail?

Abstract

Variables associated with successful completion of guardianship applications for elderly patients were identified. Thirteen patients for whom applications were approved were compared with 26 whose applications did not reach the court. Patients for whom the process was successful scored significantly higher on the anergia-depression subscale of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and had significantly more medical conditions in the past year. A survey of next of kin revealed that the process had a much better chance of success when the unit social worker made the guardianship recommendation and when family members were given more information about the taxing and time-consuming process of obtaining guardianship.

Personal autonomy and the right to make one's own treatment decisions are strongly protected rights of all citizens. Recommending guardianship, a process that could curtail these rights, should be a clinician's last resort, undertaken only after careful deliberation (1). Several authors have offered strategies that provide decision making for incapacitated patients but avoid the burdensome process of petitioning probate courts (2,3,4,5). However, when no surrogate decision maker is readily available, when an impaired person shows little insight into significant deficits, or when interested parties strongly disagree, the best interests of the impaired person may require pursuit of court-appointed guardianship.

Almost 80 percent of guardianship petitions reach the court once initiated (6), but what derails the remaining 20 percent is poorly understood. Essentially all petitions that reach the court are approved (6,7,8); therefore events that occur before court hearings must be the main contributors to unsuccessful pursuit of guardianship. We recognized that a significant number of the recommendations for guardianship originating from our geropsychiatry unit did not culminate in a guardian's being assigned to an incapacitated patient, and we devised this study to better understand why.

Methods

The institutional review board of Baylor College of Medicine approved the study protocol. We identified all patients for whom guardianship was recommended during a 24-month period (October 1993 to October 1995) at the Houston VA Medical Center geropsychiatry unit and then ascertained their eventual guardianship status. The recommendations for guardianship were based on the consensus decision of the unit's multidisciplinary treatment team. We excluded patients who already had guardians on admission to the unit and those for whom no next of kin was listed.

All of the patients underwent an extensive battery of psychological and cognitive evaluations by a multidisciplinary team. The testing included the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). The burden of illness was also assessed using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale and the Independent Activities of Daily Living Scale. Interrater reliability was .76 for the CMAI and greater than .90 for all others. We used chi square analysis to compare patients for whom the guardianship process was successfully completed and those for whom it was not.

Finally, we attempted to locate the next of kin of our patient sample to survey their impressions of the guardianship process. The relatives who were located were administered a structured questionnaire about their experience with the process.

Results

Of 305 patients admitted during the study period, 79 (26 percent) were involved with the guardianship process in some fashion. We excluded 40 who either already had a guardian or had no listed next of kin. Thus the sample consisted of 39 patients (13 percent) for whom guardianship was recommended during hospitalization.

The 39 inpatients had a mean±SD age of 72.1±7.33 years, with a range from 58 to 88 years. Thirty-eight patients (98 percent) were male. Twenty-nine participants were Caucasian (74 percent), nine were African American (23 percent), and one was Hispanic (3 percent). Eight patients (21 percent) were married, and 31 (79 percent) were not. Primary diagnoses were dementia for 25 patients (64 percent), delirium for two (5 percent), psychotic disorders for four (10 percent), mood disorders for three (8 percent), and an alcohol disorder for two (5 percent). Three patients had other disorders (8 percent).

Of the 39 patients for whom guardianship was recommended, only 13 (33 percent) completed the guardianship process. As in previous studies (6,7,8), we found that no petition that reached the court was denied, confirming the essentially 100 percent approval rate. Compared with patients for whom the process was not completed, the 13 patients had significantly higher scores on the BPRS anergia-depression subscale, indicating more severe symptoms (10±3 versus 7±3.2; t=2.67, df=36, p<.01). The 13 patients also had a greater number of medical conditions documented on DSM's axis III (5.4± 2.3 versus 3.1±1.7 conditions; t=3.19, df=30, p<.003).

No statistically significant differences were found between the groups in age, marital status, living arrangements, presence of dementia, number of diagnoses, number of medications, Global Assessment of Functioning score, CMAI rating, MMSE score, total BPRS score, or score on the HAM-D.

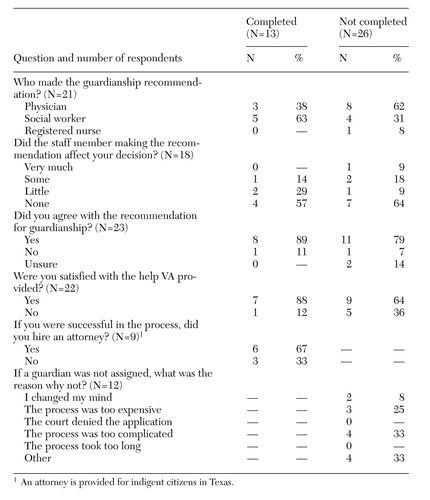

We located next of kin for 24 patients (62 percent), all of whom agreed to participate in the survey. Nine (38 percent) were relatives of the 13 patients who completed the guardianship process, and 15 were relatives of those for whom the process was not completed. Table 1 presents results of the survey, which are discussed below.

Discussion

We set out to identify variables associated with successful completion of guardianship applications in our patient population. We determined the number of patients for whom guardianship proceedings were undertaken in a cohort of older, mostly male veterans on a geropsychiatry unit, and we identified factors that distinguished the group eventually assigned guardians from those for whom the application did not reach the court. Finally, we collected some new data about the experiences of relatives of incapacitated patients who attempted a guardianship pursuit.

More than a quarter of patients admitted during the study period were involved in guardianship proceedings. About 13 percent of this group were already assigned guardians, and another 13 percent needed surrogate decision makers. The proportion of patients either assigned a guardian or involved in guardianship proceedings was larger than we had expected, even though the unit treats a population at high risk for incapacitating conditions.

We found two areas of significant difference between patients for whom the guardianship process was completed and those for whom it was not. Patients assigned a guardian had more severe depression but only as measured by a subscale of the BPRS and not the HAM-D. In addition, the guardian group had been recently treated for more medical problems. The greater need for medical care often forces caregivers to pursue guardianship because the patient is unable to give informed consent to treatment, and this need may have motivated clinicians and families to ensure that patients' guardianship petitions reached the court.

To explain the increased anergia-depression scores, we hypothesized that patients with these scores may have made little effort to make decisions, thus compelling their caregivers to pursue guardianship more urgently when problems arose. Another possibility is that more severely depressed patients required emergency guardianship to intervene in cases of high suicide risk or severe malnutrition.

We found very little else to distinguish the two groups, which was surprising. We expected that factors such as the presence of a caregiver spouse or the absence of a caregiver in the home would be associated with successful pursuit of guardianship, but they were not. Because the sample included only one woman, it is unclear what role patients' gender played in successful completion of guardianship applications.

The survey of the next of kin proved informative, although the small size of the survey sample mandates great caution in interpreting the results. In addition, survey respondents' memories about events from years earlier are inherently inaccurate.

Even though the next of kin reported that the type of professional who made the guardianship recommendation mattered little in their decision to pursue guardianship, the process had a much better chance of success when the unit social worker made the recommendation rather than the physician or nurse. We speculate that this finding may be attributable to the social worker's greater familiarity with the guardianship process or with the family or to the social worker's spending more time pursuing guardianship.

Among the next of kin surveyed, no single explanation predominated as the reason for failure of the guardianship process. Expense and complexity clearly played significant roles. Other reasons given by next of kin included inadequate assistance and ignorance of the process. It was evident that the greater and more consistent the information made available to family members, in the form of either personal assistance or written material, the more likely they were to forge ahead with the taxing and time-consuming process of obtaining guardianship.

Conclusions

This study addressed one reality of an aging population as medical, financial, and housing decisions become ever more frequent and complex. As clinicians for a growing number of incapacitated patients, we must expect to be increasingly concerned with evaluating patients' decision-making capacity and, in some cases, recommending guardianship. Once we have made such a recommendation, it is in our patients' best interests to do everything possible to ensure a successful outcome.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joseph D. Hamilton, M.D., for reviewing the manuscript; Danielle Hale for statistical analysis; and Travis Courville and Richard Workman, M.D., for help with data collection and completion of the manuscript.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College of Medicine, 1 Baylor Plaza, Houston, Texas 77030 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Burruss and Dr. Orengo are assistant professors of psychiatry, Dr. Kunik and Dr. Molinari are associate professors of psychiatry, and Ms. Rezabek is clinical instructor. Dr. Burruss is also with the department of psychiatry at Ben Taub General Hospital in Houston. Dr. Kunik is an associate in the career development award program of the Veterans Affairs Medical System health services research and development service. Dr. Molinari, Dr. Orengo, and Ms. Rezabek are also with the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of Veterans Integrated Service Network 16.

|

Table 1. Results of a survey of relatives of elderly patients for whom pursuit of guardianship was successfully completed or not completed

1. Kapp MB: Ethical aspects of guardianship. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 10:501-512, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Herr SS, Hopkins BL: Health care decision making for persons with disabilities. JAMA 271:1017-1022, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. High DM: Surrogate decision making: who will make decisions for me when I can't? Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 10:445-462, 1994Google Scholar

4. Hommel PA, Wang L, Bergman JA: Trends in guardianship reform: implications for the medical and legal professions. Law, Medicine, and Health Care 18:213-226, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Kapp MB: Proxy decision making in Alzheimer disease research: durable powers of attorney, guardianship, and other alternatives. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 8(suppl 4):28-37, 1994Google Scholar

6. Weiler K, Helms LB, Buckwalter KC: A comparative study: guardianship petitions for adults and elder adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 19(9):15-25, 1993Google Scholar

7. Keith PM, Wacker RR: Implementation of recommended guardianship practices and outcomes of hearings for older persons. Gerontologist 33:81-87, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Peters R, Schmidt WC, Miller KS: Guardianship of the elderly in Tallahassee, Florida. Gerontologist 25:532-538, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar