Compliance With Antidepressant Medication Among Prison Inmates With Depressive Disorders

Abstract

This study assessed correlates of antidepressant medication compliance among 5,305 inmates of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison system who were diagnosed as having a depressive disorder. Use of tricyclic antidepressants, male gender, and higher age were all positively associated with medication compliance scores. This investigation provided no evidence that broader use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors would improve adherence to pharmacologic treatment in this population. The results also suggest that correctional administrators may wish to target younger inmates and women with interventions to improve medication compliance.

Prison inmates in the United States are reported to have substantially higher rates of depressive disorders than the general population, even after adjustment for demographic factors (1). Because of scarce resources, pharmacotherapy is the primary mode of treatment for depressive disorders in most U.S. prisons (2). Current pharmacotherapy for depression consists predominantly of two classes of drugs: tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (3,4). Although in most clinical settings SSRIs are prescribed more frequently than tricyclic antidepressants (5), in the Texas prison system tricyclics are still considered the first-line therapy for most depressive disorders (6).

Poor adherence to prescribed antidepressant regimens can undermine the medication's effectiveness. Given the high rates of antidepressant prescribing in U.S. prisons (6), research on the correlates of antidepressant compliance is especially pertinent for practitioners in correctional institutions.

Although tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs are both associated with side effects (7), some investigators hold that patients treated with tricyclic antidepressants are more likely than those treated with SSRIs to discontinue their treatment because of adverse medication effects (5,8,9). Prescribing SSRIs should therefore result in a decrease in unnecessary work-ups and costs associated with untreated depression (5). Additionally, given the risk of overdose among prison inmates, the superior overdose safety profile of SSRIs compared with tricyclics has clinical, administrative, and economic implications. The primary goal of this study was to assess whether inmates for whom SSRIs were prescribed had better overall compliance scores than those for whom tricyclic antidepressants were prescribed.

Methods

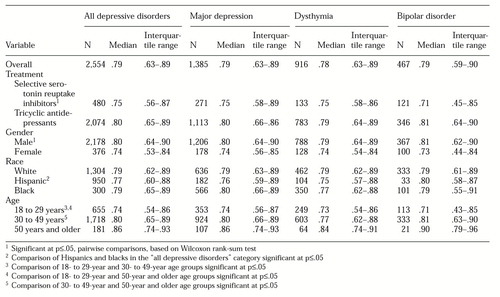

The study sample consisted of 2,554 persons who were inmates of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison system for any duration between December 1, 1998, and March 1, 1999; who were diagnosed as having major depression, dysthymia, or bipolar disorder; and who received either tricyclic antidepressants or SSRIs for at least two months during the study period. Inmates who had more than one of the three depressive disorder diagnoses during the study period were counted in the "all depressive disorders" category. Medication prescription and compliance data are maintained on all inmates for whom medication is prescribed.

For most medications, including the antidepressants in this study, inmates are required to pick up each dose at a designated "pill window." All doses taken are recorded in a computerized medical record. For this study, a medication compliance score was computed for each inmate by dividing the number of doses taken by the number of doses prescribed during the study period. Scores were calculated separately for tricyclics and for SSRIs.

Univariate analysis indicated that antidepressant medication compliance scores did not fall into a normal distribution. Therefore, a nonparametric one-way analysis of variance procedure, the Kruskal-Wallis test, was used to assess differences across the independent variables. When the Kruskal-Wallis test was significant at the .05 level, pairwise comparisons were made using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Logistic regression analysis was then employed to examine the independent association of each of the independent variables with the dichotomous dependent variable, a medication compliance score of either more or less than 50 percent.

Results

Table 1 presents median medication compliance estimates and corresponding interquartile ranges for inmates diagnosed as having depressive disorders. The overall median compliance score was .79. Inmates treated with tricyclic antidepressants had a higher median score than inmates treated with SSRIs (p<.05); men had a higher median score than women (p<.05); Hispanics had a lower median score than blacks (p<.05); and compliance scores increased with age (p<.05). Except for comparison of scores for Hispanics versus blacks, all of these associations were also found in each of the three depressive disorder subgroups.

To determine whether these associations persisted when all of the variables under study were controlled for, a logistic regression model assessing medication compliance scores above 50 percent was employed. All covariates were entered into the model simultaneously. The model revealed that for each of the three types of depressive disorder and for all three combined, inmates for whom tricyclic antidepressants were prescribed were more likely to have compliance scores above 50 percent than those for whom SSRIs were prescribed. However, the higher likelihood was statistically significant in only two of the disease categories: bipolar disorder (odds ratio=2.04, 95% CI=1.21 to 3.42) and all depressive disorders combined (OR= 1.52, CI=1.17 to 1.97).

Likewise, men were significantly more likely than women to have compliance scores above 50 percent for all depressive disorders (OR=2.01, CI=1.51 to 2.66), for major depression (OR=2.15, CI=1.42 to 3.26), for dysthymia (OR=1.77, CI=1.07 to 2.92), and for bipolar disorder (OR= 2.04, CI=1.21 to 3.42). Moreover, for each disease subgroup, age was positively associated with the likelihood of having a compliance score above 50 percent, although this finding was not statistically significant. Only minor differences in this outcome were associated with race.

Discussion

In contrast to previous investigators' findings (5,8,9), in this study compliance scores of inmates undergoing antidepressant medication therapy were slightly higher among those taking tricyclic antidepressants than among those taking SSRIs. These results must be interpreted with caution, however. Patients taking tricyclic antidepressants, which have been in use longer than SSRIs, may have been on their medication longer and thus may have become tolerant of side effects. Because information on duration of treatment was not available, the potential confounding effect of this variable could not be evaluated. Alternatively, it is possible that the pronounced sedative effects associated with a majority of tricyclic antidepressants (8,9) are well received by inmates attempting to deal with the stresses of institutional life.

Antidepressant compliance scores among the inmates in this study varied with certain sociodemographic factors. For example, men demonstrated higher overall compliance scores than women, even after other factors had been controlled for. This finding is consistent with previous reports that in noncorrectional settings women exhibit lower medication compliance in general than men (10).

Why this difference exists is not clear. As for antidepressant agents specifically, it has been suggested that some of the medication side effects, particularly weight gain, may be more poorly tolerated by women than by men (10). Moreover, women of childbearing age may fear adverse effects of medication on a potential pregnancy (10). Among female prisoners this factor might be stronger in the months immediately following their initial incarceration.

The study also showed that compliance scores were positively correlated with age. We are aware of no previously published information indicating such a monotonic increase in medication compliance associated with age.

Although this study's findings provide a foundation for further research in an untapped area, it is important to consider potential limitations of the data. First, although antidepressant medication was directly administered on a dose-by-dose basis under the direct supervision of a prison official, no external verification of whether the inmate ingested the medication, such as an open-mouth throat search, was conducted. It is possible that some inmates pretended to swallow their medication to save, store, and ultimately use the drug for nontherapeutic purposes, such as barter, recreational use at higher doses, and even suicide. Hence for some inmates high compliance may have been driven by the motivation to obtain medication for nontherapeutic purposes.

Second, differential prescription patterns may play a role in compliance patterns. However, the data used in this study permit limited insight into the driving forces behind prescription decision making—for example, the extent to which an inmate's compliance history affected his or her current prescription status. An evaluation of the association of sociodemographic variables with prescribing patterns during the same study period, discussed elsewhere (6), showed that among all Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison system inmates with depressive disorders, women received SSRIs more frequently than men, and whites more frequently than blacks or Hispanics.

Conclusions

This study produced no evidence that expanded SSRI use would improve compliance with pharmacologic treatment of depression among prison inmates. However, in view of the limitations of the data, it will be important for future investigators to examine whether similar patterns are found in other studies of inmate populations, and ultimately to assess the underlying determinants of such compliance rates.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by grant 98-CE-VX-0022 awarded by the National Institute of Justice of the Office of Justice Programs of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Dr. Baillargeon is with the department of pediatrics, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, Texas 78284-7802 (e-mail, [email protected]), and Dr. Contreras is with the department of psychiatry at the center. Dr. Grady is with the department of preventive medicine and community health, Dr. Black is with the department of internal medicine and the Center on Aging, and Dr. Murray is with Correctional Managed Health Care at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

|

Table 1. Median medication compliance estimates and interquartile ranges for inmates with depressive disorders, by antidepressant medication class and sociodemographic factors

1. Teplin LA: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. American Journal of Public Health 80:663-669, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Thorburn KM: Health care in correctional facilities. Western Journal of Medicine 163:560-564, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

3. Anderson IM: SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants in depressed inpatients: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Depression and Anxiety 7(suppl):11-17, 1988Google Scholar

4. Anderson IM, Tomenson BM: Treatment discontinuation with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. British Medical Journal 310:1433-1438, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Katzelnick D, Koback K, Jefferson J, et al: Prescribing patterns of antidepressant medications for depression in a HMO. Formulary 31:374-388, 1996Google Scholar

6. Baillargeon J, Black S, Contreras S, et al: Antidepressant prescribing patterns among prison inmates with depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, in pressGoogle Scholar

7. Trindade E, Menon D, Topfer L, et al: Adverse effects associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal 159:1245- 1252, 1998Google Scholar

8. Fairman KA, Drevets WC, Kreisman JJ, et al: Course of antidepressant treatment, drug type, and prescriber's specialty. Psychiatric Services 49:1180-1186, 1998Link, Google Scholar

9. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Wagner EH: Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:399-408, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Mogul KM: Psychological considerations in the use of psychotropic drugs with women patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1080-1085, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar