Economic Grand Rounds: Estimating Net Effects and Costs of Service Options for Persons With Serious Mental Illness

To make economically sound service planning and authorization decisions, some estimates or assumptions about the net effects and costs of service options are necessary. This study estimated the net effects and costs of several psychiatric services by comparing data for years in which clients used each service with data for years in which many of the same clients used service combinations that did not include the service.

Methods

This retrospective study used outcome evaluation data from a community mental health system serving Medicaid recipients and others in need of publicly supported services in a rural tourist area in the northern Midwest. The service area formerly included a state psychiatric hospital, which served a larger portion of the state until it closed in 1989. Thus the service area had a substantial concentration of persons with major mental illness.

The study included adults with mental illness who used client services management or assertive community treatment services and who were served for at least six months in each of at least two fiscal years between 1988 and 1996. The study included data from 2,884 client-years of service used by 542 clients.

Clients in the study ranged in age from 18 to 95 years. Fifty-five percent were female. Most were Caucasian (97 percent), with a few Native Americans (1.5 percent), blacks (.7 percent), Hispanics (.6 percent), and an Asian American (.2 percent). The most frequent ICD-9 diagnoses were schizophrenic disorders (42 percent) and major depression (34 percent).

Effectiveness measures used in the study were annual changes in the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (1) and the Role Performance Profile (RPP) ratings of clients. The RPP is a locally developed scale on which staff rate the role performance of clients in 20 areas, such as contributions to community or work, household and money management, and contact with reality. Possible scores on the RPP range from 20 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Possible scores on the GAS range from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating better adjustment.

Changes were calculated by subtracting the rating done either at the beginning of each fiscal year or at program entry from the rating done at the end of the year or at service termination. If data were missing for a client on either measure for any of the years examined, the client's data for that year were excluded. Good interrater reliability was found (r=.74) when client services managers' RPP ratings of 64 clients were compared with ratings of the same clients by outpatient or other staff. Split-half reliability coefficients of .93 and .94 were found for RPP ratings of 553 clients in 1991 and 668 clients in 1992.

Both measures were used because the GAS emphasizes problematic behavior and the RPP focuses on positive role performance.

The cost measure used was the annual cost per client, converted to 1996 dollars, for all mental health services paid for through the community mental health system and the cost of community psychiatric inpatient services. Costs paid for by the community mental health system included all services described in this study plus outpatient therapy, medication clinic services, state psychiatric inpatient services, supported independent living, mental health emergency services, and crisis residential services. Costs were calculated by multiplying the number of units of each type of service used by the client by the cost per unit for the service that year, including a spread of administrative costs. The only mental health services costs not included were costs of psychiatric medications paid for privately or by insurance and costs of any mental health services provided by the client's primary physician.

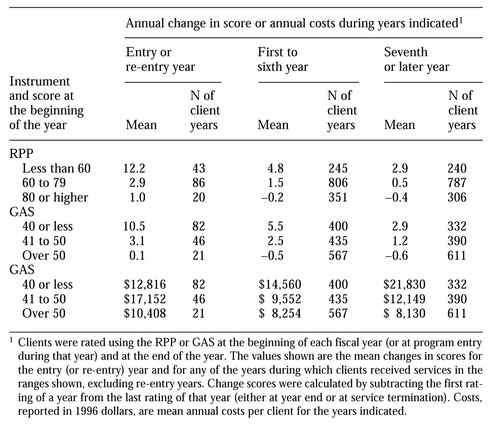

Comparing data from different years for the same clients controlled for many background and personality variables that do not change from year to year. Some variables that do change required additional controls. Table 1 shows that the year service was provided and client functioning at the beginning of the year had strong interacting impacts on changes in RPP and GAS ratings and on costs.

These variables were controlled through covariance regression analyses in which client-years of service were used as the unit of analysis. In all the covariance regressions, one covariate was year of service, scored as -1 for entry or re-entry years and with the square root of the year of service for other years. The covariates used to control for client functioning at the beginning of the year were the client's first RPP rating in the year, used in the regression analyses with RPP change as the dependent variable, and the first GAS rating in the year, used in the regression analyses with GAS change and cost as the dependent variables.

Because use of different years of service for the same clients violates the independence assumption, a third set of covariates was included to remove the effects of the dependence. These covariates were the client's average change, for all years except the one being scored, on the scale used as the dependent variable, and the client's average cost for all other years in the regression analyses with cost as the dependent variable. The interactions among the covariates were included in the covariance regressions.

During the period covered by the research, 1988 to 1996, staff-to-client ratios averaged one to eight for assertive community treatment, one to 20 for intermediate client services management, and one to 38 for brokered client services management. Both the assertive community treatment and intermediate client services teams included a nurse and an occupational therapist as well as client services managers. The brokered client services management team included only client services managers.

For all services except intermediate client services management, comparisons were made between "in-years" in which clients used the service (for all or part of the year) and "out-years" in which the same clients did not use the service but used other services. For clients who used intermediate client services management some years and assertive community treatment other years, the years in which they used assertive community treatment were excluded from the comparison for intermediate client services management. Thus the comparison would focus on the increased intensity and comprehensiveness of intermediate client services management compared with brokered client services management or outpatient services only.

Results

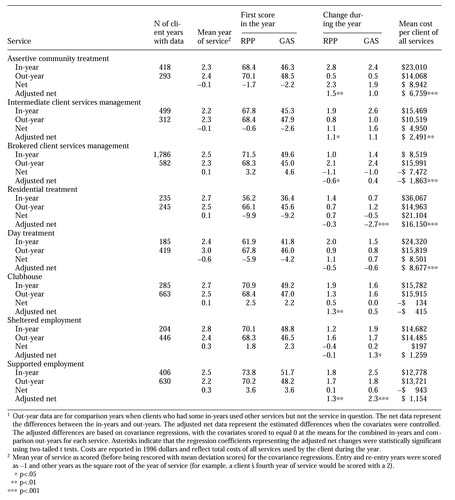

Table 2 compares outcomes and costs for in and out years. Adjusted net data represent the estimated net effects and costs when the covariates were controlled.

Both the GAS and the RPP ratings indicated that annual improvements for clients during years in which they received assertive community treatment were about five times greater than annual improvements when they were not receiving such treatment. Costs during years of assertive community treatment were less than twice as high as costs during comparison years. These differences were somewhat reduced by covariance adjustments. Based on adjusted data, annual improvements were three to four times greater and costs were only 50 percent higher for clients during years when they received assertive community treatment. Comparisons using the adjusted data were made by adding the adjusted net change (or cost) to the average out-year change (or cost) and comparing the sum to the average out-year change (or cost).

For years when clients used intermediate client services management, the adjusted data show that annual improvements were twice as great with a cost only 25 percent higher, compared with years when the clients used brokered client services management or outpatient services only.

For years in which clients used brokered services management, the net data indicate substantially reduced improvements and substantial cost savings compared with years in which they used intermediate services management or assertive community treatment. Clients started years when they used brokered services management at higher levels of functioning. Thus the adjusted data for brokered services suggest only moderately slower progress as measured by the RPP and similar or greater progress as measured by the GAS. The adjusted data also indicate moderate and statistically significant cost savings for years clients used brokered services, compared with years when they used intermediate services management or assertive community treatment.

The residential services in this study were contracted adult foster care services that were used by a client for more than 60 days in the year. For these services, the community mental health system paid $12 to $90 per day (in addition to payments from the client's Supplemental Security Income) for personal care, training, or behavior programming that was more intensive than services provided through regular foster care. For years during which clients used residential services, service costs were more than twice as high as costs in comparison years. Clients made slightly larger improvements as measured by the RPP but slightly smaller improvements as measured by the GAS in years when they used residential services. The adjusted data indicate slightly smaller RPP changes, negative GAS changes, and much higher costs compared with years when the same clients did not use residential services.

The day treatment services we examined were relatively long-term rehabilitative services planned and monitored by interdisciplinary teams. Clients used the day treatment services for several months to several years. The adjusted data indicate slightly smaller improvements during the years of use and substantial and statistically significant increased costs.

The clubhouse services examined were psychosocial rehabilitation services based on the Fountain House model. The adjusted data indicate a substantial and statistically significant improvement, as measured by the RPP, at no additional cost compared with years when the same clients used services that did not include clubhouse services.

The services labeled sheltered employment were facility-based, segregated, paid work services. The supported employment services were community-based individual job placements with job coaching, work crews, or enclaves (enclaves are small groups of client workers in workplaces where the majority of workers are not clients). The adjusted data indicate that clients experienced substantially greater improvements in years when they used supported employment than in years when they used sheltered employment. The cost of all services was no greater for years when they used supported employment than for years when they used sheltered employment.

Discussion and conclusions

This study and other research (2,3) suggest that in mental health systems that have 24-hour emergency services and that control inpatient utilization for all consumers, combinations of services that include assertive community treatment cost more than other combinations of services for the same or similar clients. In this study the added costs for assertive community treatment paid off well. A 50 percent increase in costs produced improvements that were three to four times greater than in years when the same clients used intermediate or brokered client services management.

Other research on intermediate, or intensive, client services management has produced mixed results (4,5,6). Although the net effects were not statistically significant, our study suggests that clients may progress twice as rapidly when using intermediate client services management with costs only 25 percent higher than when the same clients use brokered services management or outpatient services.

This study and others (7,8,9) show that the effectiveness of brokered, or low-intensity, client services management is not great. However, many community mental health systems may need to provide something like brokered services management to many consumers much of the time to be able to afford assertive community treatment and other more intensive services when clients need them most.

The finding of high net and adjusted net costs combined with the adjusted data indicating smaller improvements for years when clients used residential services provides support for using residential services only when they are the only safe alternative to long-term inpatient care.

Clients started years in which they used clubhouse services at higher levels of functioning than they showed at the start of other years of service; however, they still made as large or larger gains during clubhouse years. The adjusted data indicate the advantage with respect to RPP improvements was substantial and statistically significant while the costs of all services were slightly less than in years when the same clients did not use the clubhouse. This finding suggests that psychosocial rehabilitation services based on the clubhouse model are a cost-effective way for clients who are functioning fairly well to continue to improve their role performance.

The adjusted data show that clients made substantially larger improvements in years when they used supported employment than when they used sheltered employment—and at no additional costs. This finding suggests that programs should consider replacing sheltered employment with supported employment.

The adjusted net data indicate that clients experienced greater improvements in functioning in years when they used assertive community treatment, clubhouse services, and supported employment compared with years when they used day treatment but the cost of all services was higher in years when they used day treatment. This finding suggests that programs should consider replacing day treatment with these services.

This study was not experimental, and it was conducted in a single community mental health system. Thus all conclusions are tentative until tested by similar research in other systems or by experimental research. Mental health systems that have collected the same outcome data for various services over several years could conduct similar analyses and base decisions on data from their own systems. Systems that do not have such data for their services may find this study helpful in estimating the net effects and costs of their services.

Dr. Landis is supervisor for planning and evaluation at Great Lakes Community Mental Health, 701 South Elmwood, Suite 19, Traverse City, Michigan 49684 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Change scores on the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) and the Role Performance Profile (RPP) and average annual costs among clients with serious mental illness in a community mental health system, by year in the system

|

Table 2. Outcomes as measured by the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) and the Role Performance Profile (RPP) and costs among 542 clients with serious mental illness in a community mental health system comparing "in-years" when clients used a service with "out-years" when the same clients did not use a service1

1. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Chandler D, Meisel J, McGowen M, et al: Client outcomes in two model capitated integrated service agencies. Psychiatric Services 47:175-180, 1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Taube CA, Morlock L, Burns BJ, et al: New directions in research on assertive community treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:642-647, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Borland A, McRae J, Lycan C: Outcomes of five years of continuous intensive case management. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:369-376, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

5. McRae J, Higgins M, Lycan C, et al: What happens to patients after five years of intensive case management stops? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:175-179, 1990Google Scholar

6. Goering PN, Wasylenki DA, Farkas M, et al: What difference does case management make? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:272-276, 1988Google Scholar

7. Franklin JL, Solovitz B, Mason M, et al: An evaluation of case management. American Journal of Public Health 77:674-678, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Solomon P: The efficacy of case management services for severely mentally disabled clients. Community Mental Health Journal 28:163-180, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, et al: An experimental comparison of three types of case management for homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 48:497-503, 1997Link, Google Scholar