State Health Care Reform: Maryland's Medicaid Reform: Design and Development

As states reform their Medicaid programs with more emphasis on managed care systems, a key decision is how to configure the delivery of mental health services. This column provides an overview of the design and development of the Maryland system to manage publicly funded mental health services in conjunction with the state's reform of Medicaid using the section 1115 waiver. The opportunities and challenges that this system presents are discussed. This paper was prepared after approval of the Medicaid 1115 waiver by the Maryland General Assembly and the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) and before implementation of the system.

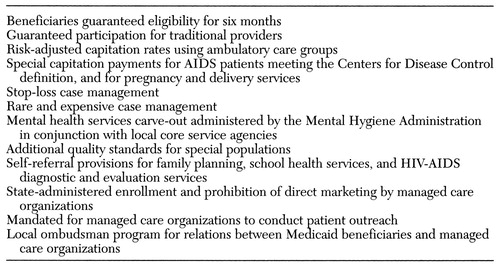

In April 1996 the Maryland General Assembly passed legislation that authorizes the state secretary of health and mental hygiene to implement a systemwide managed care program that places close to 80 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries in capitated managed care organizations for physical health care. HCFA approved the Maryland 1115 waiver proposal on October 30, 1996, and enrollment of participants began in June 1997. Features of the new program, called HealthChoice, are outlined in Table 1.

The waiver culminates a series of managed care initiatives in the last five years to slow the growth of spending in the Maryland Medicaid program in the face of mounting fiscal pressures and changes in federal and state political leadership (1).

Mental health services for beneficiaries eligible for the waiver plan are delivered through a carve-out arrangement for specialty mental health services as part of a new publicly managed mental health system. The reform extends beyond Medicaid to manage all public mental health funds under one unified system. The mental health carve-out is the only substantial services carve-out in HealthChoice. Furthermore, this model departs from the decision to integrate mental and physical health services in Maryland's primary care physician gatekeeper program that began in 1991 (2).

In the new system, eligible Medicaid beneficiaries receive medical, substance abuse, and primary mental health services from a capitated managed care organization. Because the carve-out does not include substance abuse services, it is not the same as a "behavioral health" carve-out that is common in the private sector and in some Medicaid managed care programs.

The Maryland public mental health system

The Maryland public mental health system was conceptualized and promoted by the leadership of Maryland's Mental Hygiene Administration. Like many state mental health authorities, the administration manages funds from multiple sources and oversees a broad array of services and providers. The section 1115 reform process presented an opportunity to implement a managed care system that blends together funds from Medicaid and Medicare, state general funds and grants, and other funds from forensic care appropriations, self-pay, and private-sector reimbursement.

The populations served by the public mental health system include Medicaid recipients eligible for the section 1115 waiver; Medicaid recipients not covered in the waiver, mostly Medicare recipients also eligible for Medicaid and institutionalized persons; and persons not eligible for Medicaid who are uninsured or underinsured and eligible for public mental health services because of the severity of their illness and financial need.

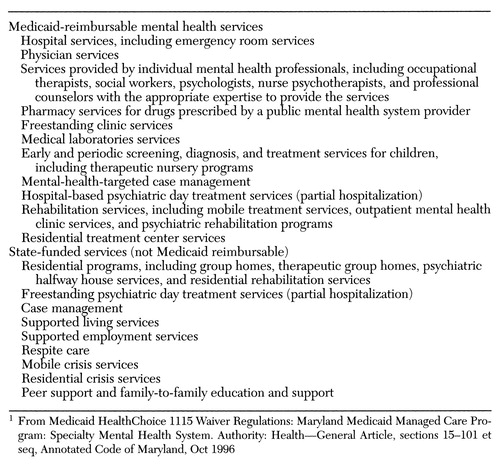

In the waiver plan, Medicaid beneficiaries are entitled to the same set of Medicaid-covered mental health services that have always been available to them (4). These services are listed in Table 2. In addition, a broad range of state-funded services that are not covered by Medicaid are available to Medicaid beneficiaries on the basis of medical necessity (4). These services are also listed in Table 2. The public mental health system can be accessed directly by self-referral or referral by a family member or caregiver, mental health provider, or primary care provider in a managed care organization.

The plan waives Medicaid's rule excluding coverage for stays by persons between age 22 and 64 in institutions for mental diseases (IMDs); instead, inpatient stays of up to 30 consecutive days per episode and a total of 60 nonconsecutive inpatient days per year in IMDs are now covered (3).

Organization and financing

Maryland's regional mental health planning and monitoring organizations, the core service agencies, oversee and manage the system at the regional level, with funds for service provision allocated by the Mental Hygiene Administration. The core service agencies were established in 1991 to define, develop, and manage the mental health system in their jurisdictions for the priority population—persons with serious mental illness or serious emotional disturbance—with assistance from the Mental Hygiene Administration (5). Under the new system, the core service agencies continue their role as agents of state and county governments while managing service delivery for a larger population that includes all Medicaid beneficiaries.

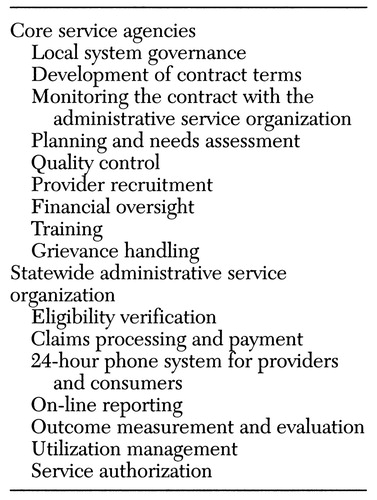

The Mental Hygiene Administration has a contract with a statewide private managed behavioral health company, Maryland Health Partners, to provide administrative services (see Table 3) on behalf of the core agencies. In contrast to many other state contracts with behavioral health organizations, under the Maryland contract, Maryland Health Partners is not a service provider and does not take on financial risk for services. Thus the company has no financial incentive to deny care.

Previously, clinics under the auspices of the Mental Hygiene Administration were financed through grant funds. The waiver plan includes a conversion of these funds to fee-for-service payments. In the future the Mental Hygiene Administration may contract with HealthChoice managed care organizations to provide capitated mental health services contingent on HCFA approval. As a result of debates in the Maryland General Assembly, HealthChoice regulations require the state to conduct a study of the feasibility of providing capitated mental health services.

Rationale

Hadley (6) outlines how changes in financing mental health services have led to "a system characterized by a multiplicity of providers which exist in a highly complex and fragmented environment." By consolidating funding, Maryland hopes to create a "one-tiered system of care governed by uniform standards" (5). This design has the potential for increased continuity of care, substitution of alternative services, and incentives for care tailored to individual needs with less constraints from rules imposed by multiple programs. In other words, the vision of state administrators is to shift from a program-centered system to a client-centered system.

In addition, because a single system is accountable for the full continuum of mental health services, the system was designed so that no financial gain is achievable through shifting costs and responsibility to other mental health sectors. This phenomenon, referred to as "dumping," arises when separate systems of care are responsible for a defined group of services. Also, under the new system, state hospital admissions are subject to utilization review for the first time.

The new design for the public mental health system builds on the strengths of existing infrastructures to serve the special needs of persons with mental illness. The infrastructures include the Mental Hygiene Administration's local governance agencies, established provider networks, and linkages with social service systems and programs. Lessons from implementation of both integrated and carved-out mental health care models in privatized managed care systems in other states suggest that new provider networks have disrupted existing systems of care (7,8).

The public mental health system is designed to combine the Mental Hygiene Administration's expertise in treating individuals with serious mental illness or serious emotional disturbance with managed care techniques and processes developed by the private sector. At a time when many Medicaid programs are following employers' ventures into at-risk capitated contracts with private companies to manage behavioral carve-outs (9), the Maryland plan uses a private firm for administrative services only. The rationale for this approach presented during the preparation of the waiver was that these are functions that most core service agencies do not have the capacity to perform and for which the private sector has demonstrated capacity and efficiency. Table 3 lists functions that remain with the core agencies and those that have been contracted to the statewide administrative service organization.

Maryland expects to enhance its ability to manage care as well as costs by purchasing administrative tools that have been tested and refined. The use of a single statewide contract also provides economies of scale and consistency. Maryland Health Partners will be paid approximately $11 million over 18 months, which represents about 1.2 percent of the $600 million annual budget for the public mental health system (10).

During the planning stage, the waiver plan was viewed as a more socially responsible approach to managed care by many stakeholders, who were concerned that private capitated behavioral care companies and managed care organizations did not have the capacity to serve those with disabling conditions such as severe mental disorders (11). The Maryland plan gives the public sector an opportunity to demonstrate that it can skillfully manage care while preserving state service dollars from profit making. Any savings accrue to the state and are not shared with for-profit entities. The option remains to test the efficiency of the profit motive in the future through alternative financing arrangements such as capitation.

Opportunities and challenges

Maryland intends to create a system that is more efficient, accountable, and responsive to consumers' needs. However, several challenges, which are described below, will be encountered in reaching this goal.

Coordination and policing of boundaries

Although the consolidation of funding streams restricts shifting of financial responsibility for individuals with mental illness, ensuring coordination is a significant challenge. Managing the boundaries between managed care organizations responsible for physical health care and the public mental health system requires ongoing planning, collaboration, and negotiation—particularly for substance abuse and pharmacy services.

Patients with a dual diagnosis of a substance use disorder and a psychiatric disorder must access two separate systems of care for treatment. Access and coordination for this population may already be problematic because of these patients' complex treatment needs and increased risk for morbidity and mortality (12,13).

For the public mental health system and HealthChoice, concerns about quality of care also focus on pharmaceuticals, which are prescribed and distributed by two systems. The public mental health system prescribes, dispenses, and pays for prescriptions for specialty mental health treatment, and managed care organizations prescribe, dispense, and pay for all others. The waiver regulations require coordination of the drug utilization review programs of the public mental health system and the managed care organizations. Several mechanisms have been designed to ensure coordination and police boundaries, including training of primary care physicians, protocols for appropriate referral and coordination, penalties for inappropriate referral patterns, and linkages between drug utilization review programs. However, the system is vulnerable to coordination failures, with substantial implications for quality, access, and cost.

Another concern is that mental health treatment traditionally provided by primary care providers in managed care organizations will be disrupted due to financial incentives to refer patients to the public mental health system. Capitation rates for the managed care organizations do not include funding for specialty mental health services, and the managed care organization's primary care providers are not permitted to bill the public mental health system for mental health services provided.

A paradigm shift for the system

The Mental Hygiene Administration considers the new system a "profound paradigm shift" for the public mental health system as its role changes from purchaser to builder of provider capacity (14). This new role is analogous to what Mechanic (15) described as the transition for health professionals—from consumer advocate to prudent allocator of resources. In the past, the core service agencies' goals and professional commitments have been congruent with those of advocates and providers. Their new role requires goals that are more similar to those of managed care organizations, goals that have been unpopular with many advocates and providers. Questions arise about core service agencies' ability to make such a substantial shift to become gatekeepers of care. Do the agencies have enough resolve to enforce the managed care protocols?

Core service agencies vary in size, age, and experience with managed care. Some are units of the county or local health department or quasipublic authorities. Others are private nonprofit organizations. Unless the core service agencies are assured that they will benefit directly from demonstrated savings in their jurisdiction, they are vulnerable to pressures from local political interests rather than statewide interests. Such a situation is analogous to what occurred with health agencies in the health planning system created in the 1970s (16).

Another transition for the agencies involves responsibility for a larger and more diverse population with heterogeneous service needs. Currently, the majority of persons for whom the Mental Hygiene Administration funds services are indigent and have severe mental disorders (5). The core service agencies must expand their provider networks accordingly, and their operations must be able to prioritize treatment needs without limiting services to Medicaid beneficiaries.

Potential for cost containment

The public mental health system operates under what is effectively a global budget with fee-for-service payment to providers, at least for the first year. To contain costs, the system relies on the managed care techniques of utilization management, referral to less intensive settings, and use of lower-cost providers. Initial savings for the Medicaid program include the amount of discount subtracted from the funds allocated to the Mental Hygiene Administration for the waiver-eligible population. (Because the Mental Hygiene Administration is the managing entity for the public mental health system, the funds appropriated for Medicaid beneficiaries eligible under the waiver were discounted to Maryland Health Partners by Medicaid.) Further savings depend on factors such as the ability of the core service agencies to enforce utilization review criteria. Eventually the system may permit capitation arrangements with providers or managed care organizations. Capitated arrangements may be necessary to achieve the savings required, especially if federal policy changes, such as a Medicaid budget cap, put greater fiscal pressure on states.

As states attempt to redesign their public mental health systems under Medicaid reform, several models of financing and delivery have emerged. The Maryland model, along with others, should be watched closely to determine how alternative plans fare in delivering high-quality care while achieving administrative efficiency and cost containment.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Stuart Silver, M.D., for his thoughtful review and comments.

When this paper was written, Dr. Oliver was director of evaluation at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County Center for Health Program Development and Management. She is now directing evaluation and outcomes studies at Maryland Health Partners, 7172 Columbia Gateway Drive, Columbia, Maryland 21046 (e-mail, [email protected]). Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D.,and Colette Croze, M.S.W.,are coeditors of this column.

|

Table 1. Key features of Maryland's HealthChoice plan

|

Table 2. Services available under Maryland's plan1

|

Table 3. Responsibilities of core service agencies and of the statewide administrative service organization

1. Oliver T: The collision of economics and politics in Medicaid managed care: reflections on the course of reform in Maryland. Milbank Quarterly 76:59-101, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Brach C: Maryland access to care (MAC): integrating care for mental illness, in Medicaid Reform: Policy in Perspective. Mental Health Policy Resource Center, May-August, 1993Google Scholar

3. Maryland Medicaid Section 1115 Health Care Demonstration Terms and Conditions. Washington, DC, Heath Care Financing Administration, Oct 1996Google Scholar

4. Medicaid HealthChoice 1115 Waiver Regulations: Maryland Medicaid Managed Care Program: Specialty Mental Health System. Authority: Health—General Article, sections 15-101 et seq, Annotated Code of Maryland, Oct 1996Google Scholar

5. Request for Proposals (RFP) for an Administrative Services Organization (ASO). DHMH-DCT-97-4106. Baltimore, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Mental Hygiene Administration, 1996Google Scholar

6. Hadley T: Financing changes and their impact on the organization of the public mental health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 23:393-405, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Bonnyman G Jr: Stealth reform: market-based Medicaid in Tennessee. Health Affairs 15(2):306-314, 1996Google Scholar

8. Managing the Medicaid Mental Health Benefit. Course material. Boston, Harvard Medical School, consolidated department of psychiatry, June 1995Google Scholar

9. Essock S, Goldman H: States' embrace of managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):34-44, 1995Google Scholar

10. Contract for an Administrative Services Organization for Benefits Management and Other Services for the Public Mental Health System. Contract control no DHMH-DCT-97-4264. Baltimore, Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and Maryland Health Partners, Dec 20, 1996Google Scholar

11. Durham M: Can HMOs manage the mental health benefit? Health Affairs 14(3):116-123, 1995Google Scholar

12. Jerrell JM, Ridgely MS: Evaluating changes in symptoms and functioning of dually diagnosed clients in specialized treatment. Psychiatric Services 46:233-238, 1995Link, Google Scholar

13. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, Wallach MA: Long-term course of substance use disorders among patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:248-251, 1995Link, Google Scholar

14. The Mental Health Services System Under Maryland's Medicaid Reform Proposal: Outline of Issues. Baltimore, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Mental Hygiene Administration, Jan 30, 1996Google Scholar

15. Mechanic D: Inescapable Decisions: The Imperatives of Health Reform. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction Publishers, 1994Google Scholar

16. Morone J: The Democratic Wish: Popular Participation and the Limits of American Government, New York, Basic Books, 1990Google Scholar