Association of General Medical and Psychiatric Comorbidities With Receipt of Guideline-Concordant Care for Depression

Depression is common ( 1 ) and associated with disability and high social costs. Evidence-based guidelines are available to facilitate clinical decision making, and guideline-concordant treatment improves outcomes ( 2 ). Yet, despite the high prevalence of depression, its associated disability, and availability of effective treatments, only 17%–36% of patients with depression receive guideline-concordant care ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ).

Understanding potential reasons for low rates of guideline-concordant depression treatment is critical for quality improvement efforts. For example, patients with general medical comorbidity may be more likely to receive depression treatment in the primary care sector, while those with psychiatric comorbidity may be more likely to be treated in the specialty sector. In turn, provider specialty might affect adequacy of depression treatment. Persons with more comorbid disorders may have more contacts with the health care system and hence greater opportunity to obtain depression treatment, suggesting that both general medical and psychiatric comorbidities lead to better quality of depression care ( 1 , 5 ). Conversely, primary care clinicians may have limited time and resources to meet clinical goals for both mental illness and chronic medical disease, implying that medical comorbidity will "crowd out" high-quality depression care ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ).

Earlier studies have yielded mixed conclusions. Patients with depression and comorbid psychiatric disorders are more likely than those with depression alone to receive minimally adequate treatment ( 4 ). Among Canadians with depression, those with chronic medical disorders were more likely than those without such disorders to receive guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy ( 8 ). Among elderly persons with depression in the United States, those with hypertension or diabetes were more likely than those without such conditions to receive guideline-concordant care (heart disease or arthritis did not change the likelihood of receiving such care) ( 9 ). Other studies have not found statistically significant adjusted associations of medical comorbidity with quality of depression treatment ( 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 10 , 11 ).

However, the earlier studies relied on self-reported data for service use, medications, and medical diagnoses. Administrative data are considered to be more reliable than self-reports, which may under- or overstate actual utilization ( 12 , 13 ) and bias estimates of the predictors of utilization ( 14 ). Self-reported diagnoses are less accurate than claims diagnoses ( 15 ). Other limitations of these studies included a small sample ( 3 ), exclusion of nonelderly persons ( 9 ), use of a non-U.S. sample ( 8 ), inclusion of few medical conditions ( 9 , 10 ), and the inability to establish the relative timing of diagnoses versus treatment, allowing the possibility that the medical condition developed after the depression was treated ( 1 , 4 , 8 , 9 , 11 ). Some studies did not examine guideline concordance because of, for example, lack of data on antidepressant duration or dosage ( 1 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). Our study sought to address the limitations of self-reported data ( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ) by using administrative data from OptumHealth.

Methods

We used eligibility data linked to medical, behavioral, and pharmaceutical claims from a large OptumHealth employer group (primarily white-collar workers from the banking industry) between November 1, 2003, and November 30, 2006. The study cohort included patients aged 21 and older with a new depression diagnosis or a new antidepressant prescription following a "washout" period of four or more months without any indication of depression. Individuals were excluded if they had bipolar disorder or did not have continuous medical, behavioral, and pharmaceutical coverage through OptumHealth for the washout period and at least one year after the index date of first diagnosis or antidepressant fill after the washout period. In our final cohort (N=1,835), 1,117 entered the study because of an antidepressant prescription, 631 because of a depression diagnosis, and 87 because of both (occurring on the same index date). Inclusion of discontinuously enrolled patients did not alter the study conclusions. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, Los Angeles, as part of a larger project.

Outcomes were indicators of guideline-concordant psychotherapy, guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy, and any guideline-concordant depression treatment starting within six months of the index date. Guideline-concordant psychotherapy was defined as six or more psychotherapy sessions during the six months after the index date using a "strict" definition, and two or more sessions using a "lenient" definition. Psychotherapy visits corresponded to Current Procedural Terminology codes for initial assessment, office, and facility psychotherapy visits without medical evaluation.

An antidepressant treatment episode had to begin within six months of the index date and last six or more months to meet the strict definition of guideline concordance (two or more months for the lenient definition). Dosages had to be within the minimum and maximum limits recommended by Micromedex, with the exception of tapering (lower doses for the first and last prescriptions in the episode). Low-dosage tricyclic antidepressants were excluded because they also have alternative medical uses.

Each individual's pharmacy claims were ordered sequentially, and all claims with a fill date within 30 days of the fill date plus days' supply of the last claim were included in the same episode. Duration was calculated as the number of days between the fill date of the first prescription and the fill date plus days' supply from the last prescription in the episode. Episodes that included claims for multiple antidepressants treated them as separate medications (that is, at least one had to be guideline concordant on its own). Estimates were similar when alternative methods of calculating episode duration or handling multiple antidepressants were used.

We used all diagnoses from the washout period to create indicators for psychiatric comorbidities (somatization, substance use, adjustment, anxiety, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders; other disorders originating in childhood; and psychotic and other psychiatric disorders) and general medical comorbidities (arthritis, asthma, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, hypertension, malignant cancer, and stroke). We then used this information to create aggregate indicators for psychiatric comorbidity only, medical comorbidity only, and both (with no comorbidity as the omitted category). We also estimated alternative specifications using the number of comorbidities, indicators for the number of comorbidities (one, two, or three or more versus none), and indicators for each specific comorbidity with an additional indicator for having both general medical and psychiatric comorbidities.

Multiple logistic regression was used to estimate differences in predicted probabilities associated with each covariate along with 95% bias-corrected empirical confidence intervals (CIs) bootstrapped using 1,000 replicate samples. All regressions controlled for gender and age group (in five-year increments).

Results

About two-thirds (N=1,266, 69%) of the study cohort were female, and over half were in their 30s or 40s (N=1,034, 56%). The most common comorbidities were hypertension (N= 279, 15%), anxiety (N=259, 14%), and arthritis (N=241, 13%). A total of 949 (52%) patients had no comorbidities, 256 (14%) had psychiatric comorbidities only, 444 (24%) had medical comorbidities only, and 186 (10%) had both.

For the entire cohort, 443 (24%) had any psychotherapy visits and 1,425 (78%) had any antidepressant prescription during the next six months. A total of 1,200 individuals (65%) received only pharmacotherapy, 218 (12%) received only psychotherapy, 225 (12%) received both, and 192 (10%) had a diagnosis but neither psychotherapy nor antidepressant therapy.

For the entire cohort, 203 patients (11%) received guideline-concordant psychotherapy using the strict definition (six or more psychotherapy visits in six months) and 350 (19%) received this therapy using the lenient definition (two or more psychotherapy visits in six months). Of the 443 individuals who received any psychotherapy, 46% received guideline-concordant treatment using the strict definition and 79% received such treatment using the lenient definition.

For the entire cohort, 430 (23%) received guideline-concordant antidepressant treatment using the strict definition (at least six months) and 811 (44%) received this treatment using the lenient definition (at least two months). Among the 1,425 individuals receiving any antidepressant treatment, 30% received guideline-concordant treatment using the strict definition and 57% received such treatment using the lenient definition. Overall, 33% (N=604) of the sample received any guideline-concordant treatment using strict definitions and 58% (N=1,066) received any such treatment using lenient definitions.

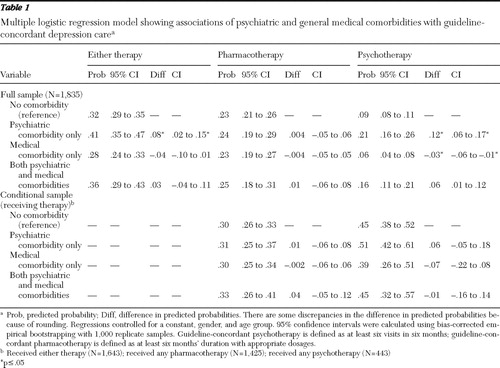

Table 1 summarizes the regression results using strict definitions of guideline concordance. Use of lenient definitions yielded similar patterns, generally with greater statistical significance. The top rows show the estimates for the full sample. The bottom rows show the estimates for patients receiving any psychotherapy and any pharmacotherapy.

|

For the full sample, having a psychiatric but no medical comorbidity increased the predicted probability of receipt of guideline-concordant psychotherapy from .09 to .21 (difference=.12, CI=.06–.17). It also raised the probability of receipt of any guideline-concordant treatment from .32 to .41 (difference=.08, CI=.02–.15), but it had no effect on the rate of receipt of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy. Conversely, having a medical but no psychiatric comorbidity reduced the predicted probability of receipt of guideline-concordant psychotherapy from .09 to .06 for the full sample (difference=-.03, CI= -.06 to -.01), but it had no significant associations with guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy or overall guideline-concordant treatment. Having both psychiatric and medical comorbidities was not significantly associated with receipt of guideline-concordant depression care.

After limiting the sample to individuals receiving therapy, there were no significant associations of receipt of guideline-concordant care with any type of comorbidity. In other words, psychiatric and general medical comorbidities were associated with the receipt of guideline-concordant treatment only as a result of their associations with the receipt of any treatment.

In analyses not shown, there were no consistent patterns of association of individual general medical comorbidities with the outcomes. However, the positive association of psychiatric comorbidities with guideline-concordant psychotherapy treatment for the full sample appeared to be driven primarily by anxiety and adjustment (mood) disorders. In both the full and conditional samples, substance use disorder was associated with lower rates of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy and hence lower overall guideline concordance. Results from the models examining the number of comorbidities suggested that effect sizes might increase with more comorbidities, but small samples prohibited drawing definitive conclusions regarding the existence of such a gradient. Finally, stratifying the regressions by the basis for study inclusion (depression diagnosis versus antidepressant prescription) yielded marginal effects that were of similar but reduced statistical significance among the smaller subsample of patients who were included due to diagnosis.

Discussion

On the basis of administrative data from a large employer group, we found suboptimal rates of guideline-concordant treatment for patients with depression; even using the most lenient definitions, only two-thirds of the sample received either psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy consistent with treatment guidelines. Furthermore, even our strict definition of guideline-concordant psychotherapy was relatively lenient, and we were unable to determine whether the psychotherapies used were evidence-based, so true rates of guideline concordance are likely to be even lower.

The probability of receiving guideline-concordant psychotherapy was higher among patients with a psychiatric but no general medical comorbidity and lower among those with a medical but no psychiatric comorbidity. No significant associations were found for receipt of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy, and patients with both types of comorbidities had guideline-concordant treatment rates that were insignificantly different from those of patients without comorbidities. Our results were robust to a range of definitions; at a minimum, our conclusions would not have changed for any definition of guideline concordance that fell between the strict and lenient definitions.

It is interesting that the associations with guideline-concordant psychotherapy were due entirely to the likelihood of receiving any psychotherapy at all. Our findings provide no evidence that comorbidities were associated with guideline concordance of psychotherapy among those receiving it. The finding that differences in rates of guideline-concordant psychotherapy were due to lack of initiation of treatment might be explained by differential referrals to psychotherapy for patients with psychiatric comorbidity and those with general medical comorbidity.

Our findings are subject to certain limitations. We studied continuously enrolled patients from a single employer group and excluded patients with untreated and undiagnosed depression, so results may not generalize. Our prevalence rates for general medical and psychiatric comorbidities were somewhat lower than epidemiologic estimates. Patients in our study were also younger than most participants in primary care-based depression research.

A few patients may have received antidepressants for conditions other than depression. Rates of guideline-concordant pharmacotherapy may be overstated because we analyzed prescription fills, not actual pills taken. Multiple comparisons could lead to spurious results, although our significant findings seemed generally consistent with broader patterns across outcomes. We were unable to adjust for clinical severity or sociodemographic characteristics other than age and gender, so we cannot rule out the possibility of confounding. However, it is difficult to think of omitted variables that could fully explain the pattern that psychiatric comorbidity increased rates of guideline-concordant psychotherapy while general medical comorbidity reduced them.

Finally, it is outside the scope of our study to examine the reasons why patients did not receive guideline-concordant care (for example, inadequate insurance benefits, medication side effects, and rapid improvement) or to distinguish between patient nonadherence and provider behavior.

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge our study is the first to examine the associations of comorbidity with rates of guideline-concordant treatment in a large, naturalistic patient population, using claims rather than self-reports to document receipt of services, prescriptions filled, and diagnoses. In contrast to most of the earlier literature, which did not find significant associations of general medical comorbidity with quality of depression care based on self-reports, our claims-based study identified an important link between guideline-concordant psychotherapy and both psychiatric and medical comorbidities.

Conclusions

Even using relatively lenient criteria, rates of guideline-concordant depression care were low, for both patients with comorbidity and those without comorbidity. The negative associations of guideline-concordant psychotherapy with general medical comorbidity, apparently because of the lower likelihood of receiving any psychotherapy, suggest that patients with medical comorbidities may not be receiving referrals for mental health services. It may be that patients with chronic medical problems have well-established relationships with their primary care clinicians, so when depression develops, their physicians choose to treat the patients themselves by using antidepressants, rather than by referring them to the mental health specialty sector for psychotherapy. Conversely, patients with psychiatric comorbidity may already get care from a mental health specialist and therefore already receive psychotherapy or have an immediate referral source for obtaining it. Although it is outside of the scope of this brief report to address mediation, an appendix describing additional analysis of provider specialty is available upon request from the authors.

The lower rates of psychotherapy use among patients with general medical comorbidities, together with existing evidence on the effectiveness of combination pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy treatment for patients with depression, suggest that it may be desirable to integrate systems of care to facilitate referrals among medical and behavioral health providers for patients for whom comanagement is appropriate. Although referrals from primary care to specialty mental health care have increased, they remain low, at about five referrals per family practitioner per year. Primary care clinicians reporting poor access to mental health specialists as a barrier tend not to refer, instead providing depression treatment themselves.

Managed behavioral health carve-outs have in part contributed to the divide separating general medical and behavioral health care, increasing the barriers for patients to be treated in both sectors. Although health maintenance organizations are naturally equipped for integrated medical-behavioral services, open systems of care can also develop infrastructure, processes, and procedures that facilitate integrated service delivery that is not usually present in independent practitioner offices. Using administrative databases, health care organizations can identify and flag cases where combination treatment is warranted or where there is medication nonadherence or treatment dropout. Coordination of health care can be facilitated by colocation of medical and behavioral care managers, who in turn comanage cases. These collaborative systems of care delivery can help improve referral rates when appropriate, can monitor medication adherence and treatment compliance, and may increase receipt of guideline-concordant care among patients who could be appropriately comanaged for depression treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant P30MH068639 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Ken Wells, M.D., M.P.H.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC: Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:284–292, 2000Google Scholar

2. Fortney J, Rost K, Zhang M, et al: The relationship between quality and outcomes in routine depression care. Psychiatric Services 52:56–62, 2001Google Scholar

3. Nutting PA, Rost K, Smith J, et al: Competing demands from physical problems: effect on initiating and completing depression care over 6 months. Archives of Family Medicine 9:1059–1064, 2000Google Scholar

4. Teh CF, Reynolds CF III, Cleary PD: Quality of depression care for people with coincident chronic medical conditions. General Hospital Psychiatry 30:528–535, 2008Google Scholar

5. Dickinson LM, Dickinson WP, Rost K, et al: Clinician burden and depression treatment: disentangling patient- and clinician-level effects of medical comorbidity. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23:1763–1769, 2008Google Scholar

6. Klinkman MS: Competing demands in psychosocial care: a model for the identification and treatment of depressive disorders in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:98–111, 1997Google Scholar

7. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al: The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Archives of Family Medicine 9:150–154, 2000Google Scholar

8. Kurdyak PA, Gnam WH: Medication management of depression: the impact of comorbid chronic medical conditions. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 57:565–571, 2004Google Scholar

9. Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC, et al: The influence of comorbid chronic medical conditions on the adequacy of depression care for older Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53:2178–2183, 2005Google Scholar

10. Bogner HR, Ford DE, Gallo JJ: The role of cardiovascular disease in the identification and management of depression by primary care physicians. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14:71–78, 2006Google Scholar

11. Koike AK, Unützer J, Wells KB: Improving the care for depression in patients with comorbid medical illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1738–1745, 2002Google Scholar

12. Evans SW: Mental health services in schools: utilization, effectiveness, and consent. Clinical Psychology Review 19:165–178, 1999Google Scholar

13. Bhandari A, Wagner T: Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Medical Care Research and Review 63:217–235, 2006Google Scholar

14. Cleary PD, Jette AM: The validity of self-reported physician utilization measures. Medical Care 22:796–803, 1984Google Scholar

15. Fowles JB, Fowler EJ, Craft C: Validation of claims diagnoses and self-reported conditions compared with medical records for selected chronic diseases. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 21:24–34, 1998Google Scholar