Economic Grand Rounds: Psychological Distress and Depression Associated With Job Loss and Gain: The Social Costs of Job Instability

Community mental health professionals are keenly aware of the rising social costs of a contracting economy. Earlier this year employee assistance programs reported increased call volume regarding violence and psychosis in the workplace, and many programs have expanded service referrals to include marriage and family counseling, child and elder care services, legal advice, and financial planning and debt counseling ( 1 ).

Researchers have shaped the scholarly debate about employment and mental health with both theoretical and empirical contributions. Jensen and Slack ( 2 ) challenged researchers to develop a new paradigm to guide research, policy, and practice to ease the social costs of underemployment. In the 20th century, employment could be viewed as a social contract for a lifetime career with retirement support. A new paradigm must account for short-term, arm's-length employment contracts and disappearing pension benefits, which have resulted in real and perceived increases in job instability.

More than a decade of research suggests that calculating social costs on the basis of unemployment, which is generally defined as not having a job but actively seeking one, is too narrow. Underemployment has been proposed as an operative concept for personal economic hardship; it includes a level of employment that would not be predicted by human capital theory in smoothly functioning markets ( 3 ). Employed persons now include those who accept jobs with limited growth opportunities that do not reflect their skills, abilities, or preferences—bad jobs versus good jobs. Increasingly the divergence between good and bad jobs reflects and reinforces disparities in income, education, and wealth accumulation in the United States and abroad ( 4 ). Empirical measures of the social costs of unemployment have included personal outcomes of depression, alcohol abuse, violence, and health care costs ( 5 ).

This study examined associations between social costs (depression status and psychological distress) and employment status. Rather than categorizing individuals as employed or unemployed, we sought to expand on previous studies by including two categories reflecting job instability: recent job loss and recent job gain.

Methods

We used 2004–2007 data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), a multiyear, large-scale, nationally representative survey that tracks individual health care use and employment dynamics ( www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/data_overview.jsp ). Each year MEPS fields a new panel, and the survey then collects two calendar years of information from each panel household in a series of five six-month rounds of data collection over two-and-a-half years (interviews at six, 12, 18, 24, and 30 months). The public-access MEPS household component includes information from questionnaires fielded to individual household members and their medical providers. The sampling frame for this component is drawn from respondents to the National Health Interview Survey, a nationally representative sample of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. A study exemption for public use data was obtained from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

The population of inference is the U.S. noninstitutionalized population of working-age persons (18 or older) who did not report retirement at any point during data collection. To avoid cyclical influences, we chose years 2004 to 2007—a period of economic expansion. In addition, the MEPS samples in these years were the most recent for which measures of psychological distress were used. We combined the 2004–2007 MEPS full-year consolidated data files to generate an analytical cohort with robust sample size.

The MEPS survey documents employment status for all persons aged 16 or older. Four mutually exclusive responses are possible: "currently employed," or had a job on the interview date; "has a job to return to," or did not work during the data collection round (since the previous interview) but had a job to return to on the interview date; "employed during the round," or had no job on the interview date but worked during the round; or "not employed with no job to return to," or did not have a job on the interview date, did not work during the round, and did not have a job to return to.

For the study reported here, employment was assessed for each of the MEPS calendar years. "Employed" was defined as a "current main job" during the year (same as "currently employed" above). "Job gain" was not being employed in one round and having a current main job in a later round that year; and "job loss" was the converse. "Unemployed" was "not employed with no job to return to" for all rounds during the year.

Psychological distress was assessed with the Kessler 6 (K6), a community-based, validated epidemiologic measure of nonspecific psychological distress ( 6 ). It assesses feelings in the past 30 days with a 5-point scale: none of the time, a little, some, most, or all of the time. Higher scores indicate a greater likelihood of mental disability and distress. Feelings of being nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, and sad are assessed, as well as feeling so depressed that everything is an effort and feeling worthless. Employment status was measured in the round in which the K6 questionnaire was administered. Distress related specifically to depression was also documented. We created comparison cohorts with current depression (at least one ICD-9 code 311 reported by a medical provider in any round in the year) and with no depression.

Reduced-form models tested the association of the K6 subscales and employment status, adjusting for demographic variables. Using Stata, version 11, we ran empirical models for the 2004–2007 respondents with sample weights to derive nationally representative estimates. Ordered logistic regression was used to statistically test differences in K6 subscale scores for employment and depression status subgroups.

Results

The results are based on 81,097 respondents from 2004–2007: 73% were employed, 23% were unemployed, 4% experienced job loss, and less than 1% experienced job gain. Just under 10% had a depression diagnosis in the year of observation.

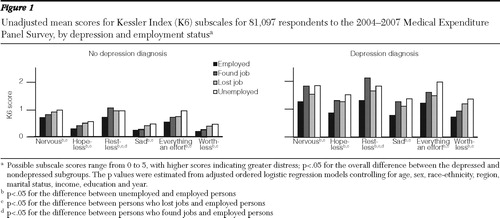

As shown in Figure 1 , associations between employment status and measures of psychological distress were generally significant regardless of depression status. For both the depressed and nondepressed subgroups, unemployed persons had significantly greater psychological distress than those who were employed. In addition, those who lost a job had significantly greater distress than employed persons.

However, for the depression subgroup, the magnitude of the association between nonspecific psychological distress and employment status was roughly double that of the nondepressed subgroup. Total K6 scores for the depressed subgroup were on average just over 6 points higher (the aggregate of each subscale) than for the nondepressed subgroup, indicating a clinically and statistically significant difference (regression results not reported). Depressed persons who experienced job loss or unemployment were significantly more distressed than depressed persons who were employed. On all K6 subscales except one (feeling worthless), unadjusted distress levels for persons who gained a job were higher than those of depressed persons who had lost a job. Adjusted differences were statistically significant for job gainers compared with employed persons only for the restlessness subscale.

Discussion and conclusions

The results are consistent with those of previous studies showing that rates of depression are higher among unemployed persons than among employed persons. This work extends previous findings by examining depression rates among persons who experienced job transitions—job loss or gain.

Persons without depression who experienced job loss were significantly more distressed than employed persons. Among persons without depression, psychological distress as measured by K6 subscale scores was not significantly different in adjusted models for those who experienced job gain and those who were employed (except for the restlessness subscale). However, among these persons with depression, unadjusted levels of distress were higher for job gainers than job losers in all subscales except worthlessness. For clinical and policy purposes, it is the unadjusted levels that matter, because people who seek help start with a global, unadjusted score.

Many years ago Holmes and Rahe ( 7 ) demonstrated that starting a new job was a stressful life event—almost as stressful as losing a job. However, we found that among depressed persons, those who gained jobs were more symptomatic than those who lost jobs on some scales that measure feelings associated with specific symptoms of depression. The association between psychological distress and job gain, particularly notable in the depressed subgroup, may be related to the concept of underemployment. Some job seekers may have taken jobs with lower wages, poorer working conditions, fewer advancement opportunities, less generous benefits, or fewer hours than they had desired. Persons with a disorder such as depression may be more likely to be underemployed. Because this study design did not allow for causal interpretation of the findings and statistical significance was not observed for all endpoints, alternative interpretations cannot be ruled out.

The 2001–2007 economic expansion was long by postwar standards but has generally been considered anemic for the working American. Improvement on major economic indicators was based on unprecedented productivity growth and a housing market bubble and was not matched by expansion in job creation ( 8 ). The implication for the recent recession (December 2007–June 2009) is that persons who gain jobs are an important population to watch. Among them are many young people working in their first job after graduation. Therefore, studies of this subpopulation will provide important measures of who bears the social costs of underemployment.

This study had several limitations. Conclusions about causal relationships between unemployment and psychological distress cannot be drawn from these panel data. The social contagion hypothesis that bad events lead to depression or the selection hypothesis that people with impaired psychological functioning are at risk of being laid off cannot be untangled here ( 9 ). We did not empirically define underemployment or characterize good and bad jobs, although that could be calculated by using MEPS data in future work. We did not compare periods of economic expansion and contraction or growing and shrinking industries. MEPS 2008 data will permit researchers to examine the recent recession.

Future studies should assess the interaction between employment status and economic environment and its impact on psychological distress. For example, research should explore whether the social costs of unemployment are higher when others with similar job status are also losing jobs in a recession or when others are relatively secure in an expansion. Social costs in addition to psychological distress need to be examined, including the impact of underemployment on physical and mental functioning and health-related quality of life. Implications of these findings suggest that a federal jobs bill should include linkage to mental health services and other services that are needed by people facing personal economic hardship. Indeed, perhaps the jobs bill should extend benefits for at least a year after work is obtained, because people who gain jobs appear to be a population at risk of mental illness and associated medical ills.

1. McQueen M: Recession's mental toll. Wall Street Journal, Mar 7, 2010Google Scholar

2. Jensen L, Slack T: Underemployment in America: measurement and evidence. American Journal of Community Psychology 32:21–31, 2003Google Scholar

3. Dooley D, Catalano R: Introduction to underemployment and its social costs. American Journal of Community Psychology 32: 1–7, 2003Google Scholar

4. Burgard S, Brand JE, House JS: Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Social Science and Medicine 69:777–785, 2009Google Scholar

5. Catalano R: Health, medical care, and economic crisis. New England Journal of Medicine 360:749–751, 2009Google Scholar

6. Kessler R, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al: Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine 32:959–976, 2002Google Scholar

7. Holmes TH, Rahe RH: The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 11:213–218, 1967Google Scholar

8. Information on Recessions and Recoveries, the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee, and Related Topics. Cambridge, Mass, National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at www.nber.org/cycles/main.html Google Scholar

9. Dooley D, Catalano R, Wilson G: Depression and unemployment: panel findings from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. American Journal of Community Psychology 22:745–763, 1994Google Scholar