Population-Attributable Risk of Suicide Conferred by Axis I Psychiatric Diagnoses in a Hong Kong Chinese Population

Suicide is a globally recognized public health issue. Many well-conducted risk factor studies, mostly case-control psychological autopsy studies, have consistently demonstrated that 90% or more of suicide victims have diagnosable psychopathology at the time of death ( 1 ). A meta-analysis of psychological autopsy studies showed that affective disorders are most common (30%–90%), followed by substance use disorders (19%–60%) and schizophrenia (2%–14%) ( 2 ). The suicide death toll in China is huge, accounting for about 50% of all global suicide deaths ( 3 ). Given the cross-national difference in trends and correlates in the epidemiologic profile of suicide, few case-control psychological autopsy studies have been conducted to address the psychosocial risk factors for suicide specific to this locality. Chinese communities in different parts of the world are diverse in socioeconomic situations. An earlier multisite and multiethnic (Han Chinese and aboriginal Taiwanese) case-control psychological autopsy study in Taiwan (N=339), where the socioeconomic development is in general more advanced than in other parts of China, found that 97%–100% of suicide decedents from all age groups had DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders ( 4 ). A multisite case-control psychological autopsy study (N=1,055) conducted by Phillips and colleagues ( 5 ) in representative rural and urban areas in the People's Republic of China found at least one lifetime DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis among 63% of suicide decedents. Another study reported that 86% of a group of 170 Chinese suicide decedents aged 65 and older in Hong Kong, a highly urbanized part of China, had at least one DSM-IV axis I disorder ( 6 ).

As persuasive as these studies might be, the findings are related specifically to the study samples. Public health planning requires that consideration be given to whole-population data. Policy makers need data on population-attributable risk (PAR) to formulate effective evidence-based policies that target the most important risk factors ( 7 ). PAR provides a measure of the proportion of a condition that can be attributed to exposure to a risk factor. Such a figure implies the proportion of a condition that would be eliminated in the group exposed to the risk factor if that risk factor were eliminated. Few suicide studies address PARs of individual risk factors, aside from reporting the strength of associations as expressed with odds ratios and relative risk ratios. Some community-based studies have used PAR to examine the importance of depression in suicidal behavior and ideation ( 8 , 9 , 10 ), but these studies have focused on a single risk factor without regard to other factors.

Most psychiatric and psychosocial risk factors identified in psychological autopsy studies that have used a stringent and in-depth psychosocial inquiry approach are unlikely to be replicable in epidemiologic surveys or studies based on surveillance data at the population level. Bruzzi and colleagues ( 11 ) described the statistical approach to calculate percentage of population risk (etiologic fraction) in general multivariate analysis, with emphasis on using data from case-control studies. A summary of attributable risk for multiple risk factors can thus be estimated, with or without adjustment for other (confounding) risk factors. Thus the use of a case-control psychological autopsy database to enumerate PARs for risk factors is a feasible alternative to the use of population data and permits public policy planning without sacrificing the number of risk factors analyzed.

Using a case-control psychological autopsy database on youth and adult suicides in Hong Kong in 2002–2004 ( 12 ), we aimed to enumerate PARs of subgroups of decedents' axis I psychiatric disorders and their related clinical factors. This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong and Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and New Territories East Cluster, and the Ethics Committee of the Department of Health, Hong Kong SAR.

Methods

The primary database for this study was from a case-control psychological autopsy on suicides among 15- to 59-year-olds in 2002–2004 in Hong Kong. The methodology and overall results are detailed elsewhere ( 12 ). In brief, a total of 1,038 suicide cases from the target age group were identified through the local judicial system (coroner's office), which is the only official source of suicide surveillance data in our locality. This source also has authorized access to the contact information of the informants (next of kin) of each suicide decedent.

The potential informants were recruited by two methods, through the government's forensic pathology service and through the coroner's office. These judicial departments either approached the potential informants face to face in the course of legal proceedings or sent out letters of invitation on behalf of our research team. Via either pathway, 1,038 potential informants were approached (one informant per case), and the first 150 informants who gave written consent to the study were included. A previous report of the main findings of this psychological autopsy study described the sample pool for the control group ( 12 ). This pool included 2,219 individuals randomly selected from 4.8 million people aged 15–59 years in Hong Kong. These 2,219 individuals had participated in another epidemiologic survey. The 150 persons in the control sample were matched for age (±5 years) and gender with the suicide decedents and were recruited from this sample pool. The closest relatives (one informant per matched control participant) were invited to participate in the interviews to give information on the same set of questions used in the psychological autopsy interviews concerning the suicide decedents.

Details of the assessment tools used have been reported elsewhere ( 12 ). Our psychological autopsy team consisted of two psychiatrists (EYHC and SSMC), one clinical psychologist (PWCW), and four research assistants who all had degrees in psychology and were experienced in conducting psychosocial interviews. The semistructured psychological autopsy interview, which lasted for 2.5–3.0 hours, contained questions pertaining to sociodemographic profile, circumstances surrounding suicide, lifetime and family history of suicide, life events and social circumstances, clinical variables (psychiatric disorder, general medical health, and health care utilization), and psychological factors (impulsivity, coping, and healthy lifestyle). The same questionnaire (with the circumstances surrounding the index suicide excluded) was applied in the research interviews with informants of the control-group participants.

A locally validated version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) was used to develop best estimates of DSM-IV-TR diagnoses ( 13 ) of axis I psychiatric disorders among both decedent cases and persons in the control group. This version of the SCID-I was reported to be reliable ( κ =.77) in measuring bipolar disorders, other affective disorders, and schizophrenia among Hong Kong Chinese ( 14 ). In addition to modules A through J in the DSM-IV SCID-I manual, we enriched our SCID-I assessment with DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling. Apart from using the SCID-I, we also identified psychiatric disorders from relevant medical information contained in the coroner's record. The final diagnoses were made at consensus meetings within the research team.

We used SPSS-PC software version 12.0 for statistical analyses in all our computations. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression models were used to analyze the contributions of individual psychopathological and social risk factors to suicide outcome.

Results

Suicide decedents in this study were all ethnic Chinese; there were 96 males and 54 females, with a mean±SD age of 38.7±11.3. There was no significant difference in the age distributions between our study sample and all suicide victims aged 15–59 in the study period. The male-to-female ratio in our sample was 1.78:1, which was comparable with the gender ratio (1.92:1) of all suicide decedents aged 15–59 whose information was archived in the coroner's database. The three most common suicide methods were jumping from height, carbon monoxide intoxication by charcoal burning, and hanging. Chi square statistics showed that profiles of suicide method were comparable between our study sample and all suicide decedents aged 15–59 during the study period.

Among 150 suicide decedents included in this study, 121 (81%) met criteria for at least one axis I psychiatric disorder (either current or lifetime diagnosis). Only 14 (9%) participants in the control group were found to have an axis I psychiatric disorder. The profile of axis I psychiatric disorders in suicide decedents was as follows: 42 cases (28%) with major depressive disorder, current episode; 35 cases (23%) with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder; 32 cases (21%) with addiction-related disorders (alcohol or substance use disorders or pathological gambling); and 43 cases (29%) of other psychiatric diagnoses, which included anxiety and phobic disorders, dysthymia, adjustment disorders, and past major depressive episode. Thirty-seven of 150 suicide decedents (25%) had more than one psychiatric diagnosis (comorbidity).

Among 121 suicide decedents with axis I diagnoses, 72 (60%) had consulted primary care physicians or other nonpsychiatric specialists and 52 (43%) had received treatment from psychiatrists in the six months before death. The overall service contact rate is compatible with other case-control psychological autopsy studies (25%–60%) ( 1 ). Eighty percent of suicide decedents with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder had seen psychiatrists in the last six months of life. For those with current major depressive disorder, the psychiatric service contact rate was 43% six months before committing suicide. Only 36% of suicide decedents with other diagnoses, such as anxiety or phobic disorder, dysthymia, adjustment disorder, and past major depressive episode, had consulted psychiatrists in their last six months of life.

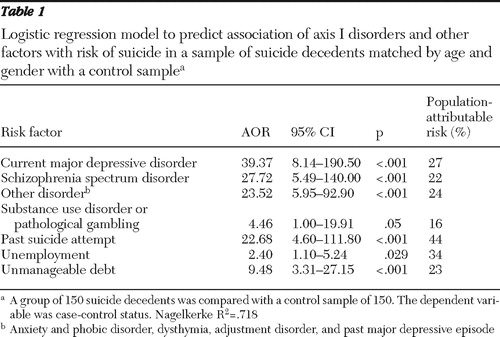

In this study, we built a secondary multivariate model on the basis of the preliminary significant risk factors that resulted from the primary model reported by Chen and colleagues ( 12 ). With suicide status as the outcome (dependent) variable, we calculated the odds ratios of subgroups of axis I psychiatric diagnoses in a logistic regression model, taking into account the independent risks contributed by comorbidity, unemployment, past suicide attempt, and unmanageable debt ( Table 1 ). Comorbidity was excluded from the final model because the p value for exp(B) (that is, the odds ratio) did not reach a significant level. The variance explained by this secondary model remained high (Nagelkerke R 2 =.718).

|

From the regression parameters of our adjusted multivariate model, we estimated the PAR conferred by each subgroup of axis I psychiatric diagnoses, taking into account the effects of other psychosocial variables. The following equation was used, and the results are shown in Table 1 :

represents the relative risk for the i th individual.

represents the relative risk for the i th individual.

In the presence of other non-disease-related variables, such as unemployment and unmanageable debt, past suicide attempt independently accounted for 44% of the PAR for suicide, followed by current major depressive disorder (27%), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (22%), and addiction-related disorders (16%). Other diagnoses (such as anxiety or a phobic disorder, dysthymia, adjustment disorders, and past major depressive episode) accounted for 24% of the PAR.

Discussion

Our results must be interpreted with consideration of the methodologic limitations of this study. The judicial barrier posed by the Privacy Ordinance of Hong Kong limited our direct access to a number of potentially eligible cases. Hence, biased sampling of suicide cases might have caused over- or underestimation of certain risk factors, and the magnitude of such discrepancy could not be ascertained. Despite the limitation, our study sample retained profiles in age and gender distribution and suicide methods that were comparable among all suicide victims aged 15–59 who died in the study period.

Among the axis I psychiatric diagnoses, current major depressive disorder accounted for the highest PAR, and yet the psychiatric service utilization rate in this group of suicide decedents was below 50% shortly before suicide. Equally alarming was the suicide risk conferred by other psychiatric diagnoses apparently not classifiable as serious mental illness—adjustment disorders, anxiety and phobic disorders, as well as past major depressive disorder—which were often labeled as low-risk cases. Taken together, the underutilization of mental health services is alarming given the accessible nature and comprehensive care provided in the local mental health system. Hence the overall mental health system may not be sensitive enough to detect suicide risk among service users and to react assertively to crisis situations.

The second common psychiatric diagnosis found among the suicide decedents of our sample was schizophrenia spectrum disorders (23%), which accounted for 22% of the PAR for completed suicide. Such high prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders was not found in psychological autospy study samples of comparable age groups from other representative Chinese communities in Taiwan and Mainland China, where less than 10% of suicide decedents were found to have schizophrenia ( 4 , 5 ). Phillips and colleagues ( 15 ) estimated that schizophrenia accounted for 9.7% of the PAR for completed suicide in the total population in Mainland China. Against this background, the observed higher PAR for suicide associated with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (23%) in Hong Kong Chinese 15–59 years old is intriguing given the high rate of service contact (around 80%) for this group in our study sample. We speculate that schizophrenia patients in an urbanized social environment are highly vulnerable to many aspects of city life and that the level of assertiveness and sensitivity of our generic mental health system might not have met the social needs of these vulnerable individuals.

Conclusions

From a public health perspective, there should be specialized mental health strategies for suicide prevention among the high-risk clinical population. These policies might include improving collaborative care with community gatekeepers (such as primary care physicians and social work professionals), launching public health campaigns to promote mental health awareness and efficient service utilization, extending the assertive community psychiatric service to risk groups (including those with past suicide attempts) other than psychotic patients with a history of violence, and enriching community-oriented rehabilitation programs for patients with schizophrenia to facilitate community adjustment and problem solving among these individuals.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study was supported by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust (which underwrote this research study via the Chief Executive's Community Project List 2002) and the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (to Dr. Sandra Chan, CUHK 4373/03M, project code 2140401). The authors acknowledge support from the International Clinical, Operational, and Health Services Research and Training Program Award D43 TW054814, funded by the National Institutes of Health for the University of Rochester's Center for Suicide Research and Prevention. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Coroner's Court in facilitating case recruitment and data collection. The authors are grateful to H. K. Mong, M.D., K. L. Hau, M.D., and Bobby Shum, M.D.; all staff at the mortuaries; and the Department of Health for supporting the study and assisting in case recruitment of informants at the public mortuaries. The authors also thank Tony Leung for his advice on the enumeration of population-attributable risk.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Cavanagh, JTO, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, et al: Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine 33:395–405, 2003Google Scholar

2. Beskow J, Runeson B, Asgard U: Psychological autopsies: methods and ethics. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 20:307–323, 1990Google Scholar

3. Suicide and attempted suicide: China, 1990–2002. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 53:481–484, 2004Google Scholar

4. Cheng ATA: Mental illness and suicide: a case-control study in east Taiwan. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:594–603, 1995Google Scholar

5. Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, et al: Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet 360:1728–1736, 2002Google Scholar

6. Chiu HFK, Yip PSF, Chi I, et al: Elderly suicide in Hong Kong: a case-controlled psychological autopsy study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:299–305, 2004Google Scholar

7. Nothridge ME: Annotation: public health methods—attributable risk as a link between causality and public health action. American Journal of Public Health 85:1202–1204, 1995Google Scholar

8. Beautrais A: Risk factors for suicide and attempted suicide among young people; in National Youth Suicide Prevention Strategy: Setting the Evidence-Based Research Agenda for Australia. Canberra, Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Health and Aged Care, 1999Google Scholar

9. Goldney RD, Wilson D, Dal Grande E, et al: Suicidal ideation in a random community sample: attributable risk due to depression and psychosocial and traumatic events. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:98–106, 2000Google Scholar

10. Pirkis J, Burgess P, Dunt D: Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Australian adults. Crisis 21:16–25, 2000Google Scholar

11. Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, et al: American Journal of Epidemiology 122:904–914, 1985Google Scholar

12. Chen EYH, Chan WSC, Wong PWC, et al: Suicides in Hong Kong: a case-control psychological autopsy study. Psychological Medicine 36:815–825, 2006Google Scholar

13. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

14. So E, Kam I, Leung CM, et al: The Chinese Bilingual SCID-I/P Project: stage 1—reliability for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry 13:7–18, 2003Google Scholar

15. Phillips MR, Yang G, Li S, et al: Suicide and the unique prevalence pattern of schizophrenia in mainland China: a retrospective observational study. Lancet 364:1062–1068, 2004Google Scholar