Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Caregiver Strain and the Use of Child Mental Health Services: A Structural Equation Model

Barriers to accessing mental health care constitute a more significant problem for children from racial or ethnic minority groups than for non-Hispanic white children. The Surgeon General has reported that because the United States is observing a rapid growth of minority youth populations, our health care system faces new challenges in keeping pace with the diverse needs of these groups ( 1 ). Although racial and ethnic disparities in child mental health services have been well documented ( 2 , 3 , 4 ), an understanding of what precipitates services use among children, and whether it varies across racial or ethnic groups, is less clear. The literature identifies two major gaps in our understanding of racial and ethnic disparities in use of mental health services by youths: lack of knowledge about the family characteristics of racial or ethnic minority populations that might have direct impact on child services use ( 5 , 6 ) and lack of information about the relationships between racial or ethnic variations in caregiving or parenting experiences and use of mental health services by youths ( 6 , 7 ).

In recent years research on child mental health services has paid increasing attention to the role of caregiver strain in services use. Studies have found that in addition to child symptomatology and impairment, caregivers' perceptions of the burden or impact of caring for a child with emotional or behavioral problems influence children's access to care, particularly access to services in which parental involvement is necessary for services use (that is, specialty outpatient services). However, few studies have examined the relationships between racial or ethnic variations in caregiver strain and use of services. It is possible that variability in caregivers' culturally influenced perceptions of caregiver strain lead to different rates of services use. The study presented here explored the role of caregiver strain in rates of services use across racial and ethnic groups. This study has been influenced by two related yet distinct fields of study: one suggesting that family stress and coping are influential factors in services use ( 8 , 9 , 10 ) and the other demonstrating racial and ethnic differences in family values, parenting practices, and family caregiving experiences ( 11 , 12 , 13 ).

We hypothesized that because children are dependent for the most part on their caregivers for accessing mental health care, cultural differences in caregiver strain will result in different rates of services use across racial and ethnic groups. Caregivers of children with emotional or behavioral problems experience a host of demands, difficulties, and strains as a result of caring for a child with special needs. These strains may include observable negative occurrences (for example, interruption of family life and financial strain) and negative emotions (for example, sadness and frustration) ( 7 ). The literature suggests that 6% to 11% of caregivers in community samples reporte caregiver strain ( 14 , 15 ) and that severity of the child's problem and a history of caregiver psychopathology contribute to increased levels of caregiver strain ( 11 , 15 , 16 ). In addition, caregiver strain is predictive of the use of child specialty services ( 2 , 15 ), use of emergency treatment and informal services ( 2 ), and treatment persistence ( 17 ), after analyses control for a child's clinical needs.

For caregiver strain, often referred to as "caregiver burden" or "family impact," there is some evidence that race and ethnicity influence caregivers' rating of caregiver strain. African-American caregivers were less likely than non-Hispanic white caregivers to appraise caring for a child with emotional or behavioral problems as stressful ( 11 , 18 ). For instance, using the same dataset used in the study reported here, McCabe and colleagues ( 11 ) found that African-American caregivers reported significantly lower levels of caregiver strain than did their non-Hispanic white counterparts, even though the study by McCabe and colleagues did not examine the role of caregiver strain in predicting racial or ethnic disparities in mental health services use. In the literature on caregivers of adult patients, African-American caregivers of dementia patients ( 19 , 20 , 21 ), of adults with mental retardation ( 22 ), and of the adults with mental illness ( 23 , 24 ) reported less caregiver strain than non-Hispanic white caregivers of these respective groups. Previous findings on Hispanic caregivers are mixed, with some studies finding that Hispanics had lower levels of caregiver strain compared with non-Hispanic whites ( 25 ) and some finding no difference between the two groups ( 11 ).

Lower levels of caregiver burden among African Americans may be attributable to a culture that has greater reliance on family social network for support, which eventually leads to less dependency on formal mental health systems ( 26 , 27 ). For example, Bussing and colleagues ( 27 ) found that African-American caregivers of children at high risk of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder reported more frequent contact with extended families and higher levels of family support than their white counterparts. When looking at racial and ethnic disparities in child mental health care, cultural differences in caregiver strain may explain underutilization of services by some racial or ethnic groups that have more collectivistic cultures with regard to family caregiving.

An inquiry into racial or ethnic differences in caregiving experiences is important for examining differential racial or ethnic representation in services use and for addressing the unique needs of families from racial or ethnic minority groups who might have distinctive cultural or linguistic barriers to using mainstream mental health services. The literature suggests that caregivers and children from racial or ethnic minority groups may enter mental heath services with greater reluctance and different expectations than non-Hispanic white caregivers and children ( 6 ). Using a secondary data analysis, the study presented here focused on caregiver strain to explain racial and ethnic disparities in use of child mental health services in three racial and ethnic groups. Specifically, we hypothesized that compared with non-Hispanic white caregivers, African-American and Hispanic caregivers would report lower levels of caregiver strain and that the effects of race or ethnicity on services use would be mediated by caregiver strain. This hypothesis was tested with structural equation models using latent variables of caregiver strain and child services use.

Methods

Sample

This study is a secondary data analysis of the Patterns of Youth Mental Health Care in Public Service Systems Study (POC) ( 28 ), which was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The POC is a longitudinal study to examine the needs for and use of mental health services among 1,448 children who were aged six to 17 years and were active in one or more of five public service sectors—child welfare, alcohol or drug treatment, juvenile justice, mental health, and public school services for children with emotional disturbance—during 1996 and 1997 in a large metropolitan area. The sample was stratified by race and ethnicity, service sector, and treatment setting (that is, home-based versus facility care setting). Primary caregivers and children completed surveys at baseline and the two-year follow-up that asked about demographic characteristics, emotional or behavioral problems, caregiver strain, and use of services. The study presented here used a cross-sectional analysis of the two-year follow-up data. Institutional review board approval and informed consent were obtained before data collection by POC researchers.

Measures

The POC assessed child psychiatric needs by administering the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV) ( 29 ) to both caregivers and children, which generated categorical DSM-IV diagnoses for children along with age of onset of each disorder. The reliability and validity of the DISC-IV are well supported for both English and Spanish versions ( 29 ). In this study a child was considered to have clinical needs if the responses (either caregiver's or child's report) indicated that full diagnostic criteria were met and that at least one moderate-level diagnosis-specific functional impairment was endorsed in the past 12 months. The diagnostic categories of child clinical need among the POC sample have been reported in previous research ( 30 )

Caregiver strain was measured by theCaregiver Strain Questionnaire (CGSQ) ( 7 ). The CGSQ is a 21-item self-report instrument measuring caregiver burden among caregivers of children with emotional or behavioral problems. It has three subscales, including objective strain (for example, disruption of family routines), subjective internalized strain (for example, sadness), and subjective externalized strain (for example, embarrassment). Three CGSQ subscales demonstrated adequate internal consistency ( α =.73–.91) ( 7 ). Possible scores on each subscale range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more strain on the caregivers.

Use of mental health services was assessed with the parent and youth version of NIMH's Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA) ( 31 ). The SACA covers lifetime and one-year use of eight inpatient, 13 outpatient, and four school-based services. A positive response on lifetime use of a particular service leads to a separate section that asks more in-depth questions about the services used in the past 12 months, including referral source, location, content, total number of days served, and payment methods. The SACA has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity ( 31 , 32 , 33 ). Mental health services use in this study is defined as any past-year use of services.

Demographic information, such as age, gender, and race or ethnicity, was gathered by child self-reports and verified by caregiver reports. Caregivers also reported whether their children had insurance coverage for mental health care.

Analysis

The measurement structures of services use and caregiver strain were tested by performing exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis, and the hypothesized relationships among the latent variables were tested by conducting structural equation modeling. Because variables for mental health services use are categorical, the mean and variance-adjusted weighted least-squares estimator was used ( 34 ). To determine the relevant covariates, age, gender, child psychopathology, and insurance status were entered into the models. All models were assessed by inspecting the statistical significance of the following four statistics: the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean residual (SRMR). Better-fitting models have higher CFI and TLI values and lower RMSEA and SRMR values. The literature suggests that CFI and TLI values should be close to .95 or higher, the RMSEA should be close to .06 or below, and the SRMR should be close to .08 or below ( 35 ). The indirect effects equal the product of the direct effects involved (for example, multiplying the X to Z and Z to Y paths equals the X to Z to Y indirect effect).

The Mplus, version 5, ( 34 ) was used for latent variable analyses that were weighted using the sampling weights. Cases with missing values on all variables (N=78) were excluded, which yielded the analytic sample of 1,370 youths.

Results

Sample characteristics

The majority of the primary-caregiver respondents were female and biological parents ( Table 1 ). There were also adoptive parents and stepparents (5%), extended family members (13%), foster parents (9%), and primary caregivers with an unknown relationship (4%). Primary caregivers were non-Hispanic white (39%), African American (28%), and Hispanic (28%). Forty-three percent (N=589) of caregivers were married; 44% had a high school diploma, and 28% had not completed high school. Two-thirds of the youths were male; 43% were non-Hispanic white, 23% were African American, and 34% were Hispanic (34%). During fiscal year 1997, 3% (N=41) received alcohol or drug treatment, 54% (N=739) received mental health services, 16% (N=219) received public school services for youths with emotional disturbance, 28% (N=384) were involved in the juvenile justice system, and 35% (N=480) were involved in the child welfare system. Finally, 83% of the youths were covered by health insurance: 25% (N=342) with private insurance and 58% (N=795) with public insurance.

|

Exploratory factor analyses of mental health services use

Because few studies have evaluated the latent structure of the SACA, we began by conducting exploratory factor analyses to establish the latent form of the SACA. Twelve items related to mental health services that were initially submitted to an exploratory factor analysis (mean and variance-adjusted weighted least-squares estimation, quartimin rotation) included specialty inpatient services; specialty outpatient services; nonspecialty outpatient services; school-based services; probation services; services received in a group home, emergency shelter, foster care, or detention center or jail; outpatient alcohol and other drug treatment; inpatient alcohol and other drug treatment; and informal services (for example, alternative healers). Standardized factor loadings <.50 were taken as evidence that an indicator had a meaningful loading on a construct. In the initial model, six items (probation services; services received in a group home, emergency shelter, foster care, or detention center or jail; and inpatient alcohol and other drug treatment) were dropped from the analysis as a result of small factor loadings. Then, using the remaining six items, a two-factor model in which the indicators of services use were specified as measuring two constructs was compared with a one-factor model in which the indicators were all specified as measures of one services use construct. Compared with a one-factor model ( χ2 =77.76, df=27, p<.001, CFI=.718, TLI=.718, RMSEA=.075, SRMR=.193), a two-factor model had better fit ( χ2 =9.32, df=27, p<.001, CFI=.982, TLI=.968, RMSEA=.025, SRMR=.042). A three-factor solution did not converge. Eigenvalues for the correlation matrix were 3.066, 1.728, and .717. Thus a two-factor model with latent constructs representing mental health services (specialty inpatient services, specialty outpatient services, nonspecialty outpatient services, and school-based services) and non-mental health services (outpatient alcohol and other drug treatment and informal services) was used for further analyses.

Confirmatory factor analysis of caregiver strain and services use

To test the constructs together, an initial model was specified with the three indicators of caregiver strain and six indicators of services use. On the basis of previous studies on the CGSQ ( 7 , 36 ), a one-factor model was specified in which objective strain, subjective internalized strain, and subjective externalized strain loaded onto the latent variable of caregiver strain. Objective strain was used as a marker indicator. Factor loadings for this combined measurement model are presented in Table 2 . The measurement model was satisfactory ( χ2 =37.12, df=15, p<.001, CFI=.968, TLI=.959, RMSEA=.032), with the indicators having loadings of >.60 on the specified constructs.

|

Structural equation modeling analysis

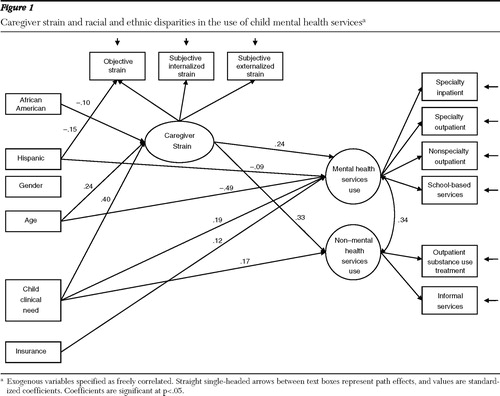

Finally, structural equation modeling analyses were performed to examine the effects of caregiver strain on the use of child mental health services among three racial and ethnic groups and to determine pathways for these effects in a multivariate context. Using the measurement models for caregiver strain and services use, the authors specified age, gender, race or ethnicity (dummy coded, non-Hispanic white was the reference group), child psychopathology, and insurance as exogenous variables, whereas caregiver strain and services use were specified as endogenous variables. Pathways were specified from racial or ethnic group to caregiver strain and from caregiver strain to two measures of services use. The model fit the data well ( χ2 =83.82, df=37, p< .001, CFI=.954, TLI=.941, RMSEA=.031) and accounted for 38% of the variance in overall mental health services use. The factor correlation for mental health and non-mental health services use was .34 (p<.001). Figure 1 presents the model complete with standardized path coefficients. The age of the youth had a significant path to caregiver strain ( β =.24) and mental health services use ( β =-.49) but not to non-mental health services use. Child psychopathology had significant direct effects on caregiver strain ( β =.40), mental health services use ( β =.19), and non-mental health services use ( β =.17). Insurance had a significant path only to mental health services use ( β =.12). Gender had no significant effects on any endogenous variables.

African-American caregivers reported lower levels of caregiver strain ( β =-.10) than did non-Hispanic white caregivers. Although Hispanic caregivers perceived lower levels of objective caregiver strain ( β =-.15) than did non-Hispanic white caregivers, Hispanic caregivers did not differ significantly from non-Hispanic white caregivers in reporting either internalized or externalized subjective strain. Being an African-American youth had no direct path to mental health and non-mental health services use, whereas being a Hispanic youth had a significant inverse direct effect on mental health services use ( β =-.09) but not on non-mental health services use. Caregiver strain indexed by three subscales of the CGSQ had a path to both mental health services use ( β =.24) and non-mental health services use ( β =.33).

Being an African-American youth had significant indirect effects on both mental health services use ( β =-.02) and non-mental health services use ( β =-.03), and these were mediated by caregiver strain. Similarly, child psychopathology had significant indirect effects on both mental health services use ( β =.11) and non-mental health services use ( β =.15), and these were mediated by caregiver strain. Finally, the age of the youth also had significant indirect effects on both mental health services use ( β =.05) and non-mental health services use ( β =.07).

Discussion

The study presented here revealed that racial and ethnic differences in caregiving perceptions, such as caregiver strain, might explain why youths from racial or ethnic minority groups have greater unmet needs than do non-Hispanic white youths. In this study, youths whose caregivers felt lower levels of caregiver strain were less likely to use mental health services. Overall, compared with non-Hispanic white caregivers, African-American caregivers had lower levels of caregiver strain and Hispanic caregivers had lower levels of objective but not subjective caregiver strain. Racial and ethnic differences in caregiver strain did not entirely explain differences in service utilization by Hispanic youths. However, the data showed that indirect effects through paths to caregiver strain were the main pathways for the effects of race and ethnicity to have an impact on services use among African-American youths.

The findings reported here are consistent with the literature on racial and ethnic differences in caregiver strain ( 11 , 18 , 37 , 38 ). Previous studies have found that compared with non-Hispanic white caregivers, African-American caregivers have lower levels of caregiver strain and Hispanic caregivers have similar levels of caregiver strain, even after the analyses control for child psychopathology and caregiving responsibilities. Reported lower burden of care among African-American caregivers of a child with emotional or behavioral problems has been attributed to a variety of causes, including a value of familism, high tolerance of family disturbance, past experience with life stressors, and religious coping, although few empirical studies have examined these potential explanations ( 11 , 18 , 27 , 39 ). More research is needed on cultural and familial factors influencing strain experienced by caregivers of children with mental health problems.

The findings of this study support the importance of culturally influenced cognitive aspects of the caregiving experience, such as perceptions of caregiver strain, in explaining racial and ethnic differences in child services use ( 40 ). Given that caregivers are the key identifiers of children's mental health problems and a critical influence on a child's entry into services, mental health research should pay more attention to how cultural and family values influence the motivation of caregivers to seek professional treatment for their children. Our finding that the effects of race and ethnicity on services use were mediated by caregiver strain, particularly for African-American youths, confirms previous studies reporting an association between caregiving strain and services use among African-American youths ( 2 , 15 , 17 ). Future research should examine why African-American caregivers tend to report lower levels of objective and subjective caregiver strain compared with non-Hispanic whites and how those factors influence children's access to mental health services.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. The study sample was a high-risk sample of children and adolescents who were in contact with the public sector of care. Thus utilization of the high-risk sample of youths may have overestimated the rates of mental health services use. An additional concern about the sample is that the study presented here is limited to high-risk youths in a large metropolitan area. The findings should not be generalized to youths with no contact with public service sectors or to youths in nonurban community settings.

Second, caregivers' and youths' self-report were used to gather data on services use. Disclosure of services use might be biased by cognitive abilities and cultural differences in comfort in reporting mental health services use, which may have underestimated service use rates for some racial or ethnic minority groups.

Conclusions

The study presented here confirmed racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services use among youths involved with public service systems. We also found that African-American caregivers reported lower levels of caregiver strain than did non-Hispanic white caregivers, and we found that caregiver strain mediated the relationship between being African American and use of mental health services. These findings suggest that cultural and family contexts in which a child's emotional or behavioral problems are recognized and in which medical advice is sought and provided may play an important role in racial or ethnic disparities and that there is a need to examine the variation in these factors if we want to reduce racial or ethnic disparities in use of professional mental health services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study (principal investigator: Dr. Shin) was supported by grant 61904 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Patterns of Youth Mental Health Care in Public Service Systems Study was supported by grant U01-MH55282 from the National Institute of Mental Health (principal investigator: Dr. Hough). The authors thank Debra J. Perez, Ph.D., for her support during the initial conception of this study, Andrea Hazen, Ph.D., Richard L. Hough, Ph.D., and John Landsverk, Ph.D., for their support during the data preparation, and Maryann Amodeo, Ph.D., for her insightful reviews of the manuscript.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

2. Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, et al: Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:1336–1343, 2005Google Scholar

3. National Institute of Mental Health Five-Year Strategic Plan for Reducing Health Disparities. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, Office for Special Populations, 2001Google Scholar

4. Zimmerman FJ: Social and economic determinants of disparities in professional help-seeking for child mental health problems: evidence from a national sample. Health Services Research 40:1514–1533, 2005Google Scholar

5. Pumariega AJ, Rogers K, Rothe E: Culturally competent systems of care for children's mental health: advances and challenges. Community Mental Health Journal 41:539–555, 2005Google Scholar

6. Yeh M, McCabe K, Hough RL, et al: Why bother with beliefs? Examining relationships between race/ethnicity, parental beliefs about causes of child problems, and mental health service use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 73:800–807, 2005Google Scholar

7. Brannan AM, Heflinger CA: The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire: measuring the impact on the family of living with a child with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 5:212–222, 1997Google Scholar

8. Costello EJ, Pescosolido BA, Angold A, et al: A family network-based model of access to child mental health services. Research in Community Mental Health 9:165–190, 1998Google Scholar

9. Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Pimley S, et al: Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology and Aging 2:171–184, 1987Google Scholar

10. Stiffman AR, Pescosolido B, Cabassa LJ: Building a model to understand youth service access: the gateway provider model. Mental Health Services Research 6:189–198, 2004Google Scholar

11. McCabe K, Yeh M, Lau A, et al: Racial/ethnic differences in caregiver strain and perceived social support among parents of youth with emotional and behavioral problems. Mental Health Services Research 5:137–147, 2003Google Scholar

12. Chan KS, Keeler E, Schonlan M, et al: How do ethnicity and primary language spoken at home affect management practices and outcomes in children and adolescents with asthma? Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 159:283–289, 2005Google Scholar

13. Alegria M, Canino G, Lai S, et al: Understanding caregivers' help-seeking for Latino children's mental health care use. Medical Care 42:447–455, 2004Google Scholar

14. Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, Angold A: Impact of children's mental health problems on families: effects on services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 5:230–238, 1997Google Scholar

15. Angold A, Messer SC, Stangl D, et al: Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Public Health 88:75–80, 1998Google Scholar

16. Brannan AM, Manteuffel B, Holden EW, et al: Use of the family resource scale in children's mental health: reliability and validity among economically diverse samples. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33:182–197, 2006Google Scholar

17. Ortega AN, Chavez L, Inkelas M, et al: Persistence of mental health service use among Latino children: a clinical and community study. 34:353–362, 2007Google Scholar

18. Kang E, Brannan AM, Heflinger CA: Racial differences in responses to the Caregiver Strain Questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies 14:43–56, 2005Google Scholar

19. Connell CM, Gibson GD: Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in dementia caregiving: review and analysis. Gerontologist 37:355–364, 1997Google Scholar

20. Fredman L, Daly MP, Lazur AM: Burden among white and black caregivers to elderly adults. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 50:S110–S118, 1995Google Scholar

21. Haley WE, Roth DL, Coleton MI, et al: Appraisal, coping, and social support as mediators of well-being in black and white family caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:121–129, 1996Google Scholar

22. Valentine DP, McDermott S, Anderson D: Mothers of adults with mental retardation: is race a factor in perceptions of burdens and gratifications? Families in Society: Journal of Contemporary Human Services 79:577–584, 1998Google Scholar

23. Horwitz AV, Reinhard SC: Ethnic differences in caregiving duties and burdens among parents and siblings of persons with severe mental illnesses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:138–140, 1995Google Scholar

24. Stueve A, Vine P, Struening B: Perceived burden among caregivers of adults with serious mental illness: comparison of black, Hispanic, and white families. American Journal of Orthopsychology 67:199–209, 1997Google Scholar

25. Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Semple SJ, et al: Across-cultural validation of coping strategies and their associations with caregiving distress. Gerontologist 37:490–504, 1997Google Scholar

26. Knight BG, Silverstein M, McCallum TJ, et al: A sociocultural stress and coping model for mental health outcomes among African American caregivers in southern California. Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 55B:P142–P150, 2000Google Scholar

27. Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, et al: Social networks, caregiver strain, and utilization of mental health services among elementary school students at high risk for ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:842–850, 2003Google Scholar

28. Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:409–418, 2001Google Scholar

29. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al: NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:28–38, 2000Google Scholar

30. Garland AF, Hough RL, McCabe KM, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in youths across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:409–418, 2001Google Scholar

31. Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, Stiffman AR, et al: Reliability of the services assessment for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 52:1088–1094, 2001Google Scholar

32. Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, et al: The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): adult and child reports. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:1032–1039, 2000Google Scholar

33. Hoagwood K, Horwitz S, Stiffman A, et al: Concordance between parent reports of children's mental health services and service records: the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA). Journal of Child and Family Studies 9:315–331, 2000Google Scholar

34. Muthen LK, Muthen BO: Mplus User's Guide. Los Angeles, Muthen and Muthen, 1998Google Scholar

35. Hu L, Bentler PM: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6:1–55, 1999Google Scholar

36. Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, Foster EM: The role of caregiver strain and other family variables in determining children's use of mental health services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 11:77–91, 2003Google Scholar

37. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

38. Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, et al: Barriers to children's mental health services. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:731–738, 2002Google Scholar

39. Williams SW, Dilworth-Anderson P, Goodwin PY: Caregiver role strain: the contribution of multiple roles and available resources in African-American women. Aging and Mental Health 7:103–112, 2003Google Scholar

40. Sue S, Zane N: The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: a critique and reformulation. American Psychologist 42:37–45, 1987Google Scholar