Health Care Utilization and Its Costs for Depressed Veterans With and Without Comorbid PTSD Symptoms

Symptoms of depression often co-occur with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Among veterans with PTSD, rates of comorbid major depression range from 29% to 68% ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). Among veterans with clinical depression, rates of comorbid PTSD are 36%–51% ( 5 , 6 ). Among depressed female veterans, rates of comorbid PTSD may be as high as 77% ( 7 ).

Persons with both depression and PTSD have high levels of symptomatic distress. They have more severe depressive symptoms, a more complicated and persistent history of mental illness ( 8 , 9 ), and higher rates of suicidal behavior than depressed patients without PTSD ( 10 ). Patients with both conditions experience greater role impairment and recover more slowly than those with PTSD alone ( 11 ). Depression and PTSD are independently associated with higher health care use and costs ( 12 , 13 ).

PTSD among veterans is a growing problem, and its care has significant consequences for staffing levels and budgets within the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) mental health system. Depression has been consistently associated with higher health care costs and utilization in both veteran and general populations ( 12 , 14 , 15 ). Most studies have also shown that PTSD patients have higher medical and surgical inpatient and outpatient utilization for physical and mental health problems than non-PTSD patients ( 7 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ). Depression and PTSD were each shown to predict costs of mental health and pharmacy services among Gulf War veterans with medically unexplained physical symptoms ( 20 ). Few studies have examined the association of depression and comorbid PTSD with health care use and costs. Using self-reported utilization data, Campbell and associates ( 5 ) found that patients with depression and PTSD were more likely to report more frequent outpatient visits than depressed patients without PTSD. The study reported here is among the first to examine, using VA administrative data, the association between PTSD symptoms, health care use, and costs in a cross-sectional sample of VA primary care patients with depression. We evaluated whether depressed patients with PTSD symptoms have greater health care use and costs than depressed patients without PTSD over a 12-month period.

Methods

This cross-sectional study compared health care utilization, antidepressant usage, and health care costs over 12 months before patients enrolled in an intervention study of collaborative care for depression. We were interested in assessing whether depressed patients with PTSD symptoms had higher utilization and costs in the previous 12 months and what types of services these patients used. We felt confident in retrospectively assessing costs before screening for PTSD because it is likely that any patient who screened positive for PTSD also would have screened positive during the previous year in which costs and services occurred. We used the Well-Being Among Veterans Enhancement Study (WAVES) secondary data set because it characterizes depression and PTSD well and contains VA administrative claims data on utilization and costs. We analyzed baseline utilization and costs data (covering the 12 months before the first survey) because they were unaltered by the intervention. We did not assess effects of the intervention, which will be reported elsewhere.

Setting and participants

A contracted survey firm conducted computer-assisted telephone interviews to determine eligibility and collect baseline data from June 2003 to June 2004. Study participants were from ten VA primary care clinics in rural and semirural areas or in small cities in five states. Study protocols were approved by participating clinics' institutional review boards and the project's administrative sites.

Screening and sampling procedures for the parent trial are presented in more detail elsewhere ( 5 ). In brief, patients in the participating VA primary care clinics were screened with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a nine-item measure of depressive symptoms ( 21 ). Those with a PHQ-9 score ≥10 were considered to have a positive screen and thus met the criteria for depression symptomatology and were included in the study. Patients who screened positive for being acutely suicidal or for bipolar disorder were excluded. The prevalence of patients with PTSD in the parent study sample was previously reported as 36% ( 5 ). Our study population included 606 veterans with depression, including 216 with PTSD symptoms and 390 patients without PTSD. We excluded 87 patients who did not consent to have administrative data collected and 68 patients who screened positive for bipolar disorder. There were no significant differences between patients who did and did not consent to have their administrative records collected.

Data sources

The WAVES survey is a 50-minute computer-assisted phone interview with questions on demographic characteristics, mental health, physical health, and health care satisfaction.

The independent variable was PTSD status. Screening positive for PTSD was defined as having three out of four PTSD symptoms in the past six months on the Primary Care-PTSD screen ( 22 ). Those with fewer than three PTSD symptoms screened negative for PTSD. At this threshold, the screen has a sensitivity level of .78 and a specificity of .89 ( 22 ).

Other survey measures used in the analysis included depression, as assessed by the PHQ-9 ( 21 ). Covariates included medical comorbidity, alcohol use, anxiety and panic symptoms, demographic characteristics, and social support. Comorbid chronic medical illnesses were assessed by the Seattle Index of Comorbidity ( 23 ). Alcohol consumption was assessed with questions from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) ( 24 ). Suicidal ideation was determined with the last item of the PHQ-9 depression scale. To assess current anxiety symptoms, patients were asked, "During the last six months, have you felt anxious much of the time?" ( 25 ). To assess panic attack symptoms, patients were asked, "In the past six months, have you had a panic attack when you suddenly felt intense fear and discomfort?" as modified from the 12-month Composite International Diagnostic Interview for the Partners in Care study ( 26 ). Other measures, including those for possible bipolar disorder and social support, are described elsewhere ( 5 ).

Barriers to health care were included as a confounder that could influence health care use and costs. These included self-reported rating of time and effort associated with attending and scheduling VA appointments.

The main dependent variables of this study were health care utilization and costs. Inpatient and outpatient utilization data were obtained from VA administrative databases. Specifically, utilization data included inpatient admissions, outpatient visits, and outpatient prescriptions filled. Outpatient visit data came from the VA Outpatient Care File, and inpatient data came from the VA Patient Treatment File. Medications and antidepressant usage data were from the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management database.

Health care visits and antidepressant medication use were assessed over a 12-month period before study enrollment. The outpatient visit was defined as a patient encounter with one or more health professionals within a single clinic. Mental health specialty visits included all mental health visits, including psychiatry, psychologist, or social work visits; visits to a substance abuse clinic; and mental health specialty-based PTSD treatment. VA inpatient admissions were defined as any inpatient admission from the Patient Treatment File. Antidepressant usage was defined as one or more times a patient filled a prescription for antidepressant medications at the pharmacy (one or more antidepressant fills). Medication measures included cumulative days' supply (the number of days antidepressants were supplied, adjusted for overlapping or concurrent prescriptions), cumulative antidepressant fills, and number of unique antidepressant prescriptions over 12 months.

Health care costs over a 12-month period before study enrollment were from the VA Decision Support System (DSS). DSS is a computerized accounting system that tracks health care costs at the individual level. Patient encounters include direct costs, such as provider time and supplies, and indirect costs, such as equipment and overhead. Costs include overhead assigned across departments ( 27 ). Outpatient costs from DSS were matched to outpatient visits in the Outpatient Care File. Inpatient costs from DSS were matched to inpatient admissions from the VA Patient Treatment File. Direct costs for medications, including antidepressants, were from the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management database and adjusted to include indirect costs. All estimates were standardized to 2005 dollars with the medical component of the consumer price index.

Analysis

For utilization analyses, we assessed health care utilization differences between depressed patients with and without PTSD over 12 months before study enrollment. Survey population weights based on age and gender were used to reflect the probability of participant entry to the study. In unadjusted analyses, two-sample t tests assessed differences between PTSD groups for continuous measures and chi square tests detected proportional differences for categorical measures. Inpatient admissions were dichotomized because of the low number of admissions. For regression analyses, because the utilization variables are count data (number of visits), we used negative binomial regression to analyze total outpatient and medical care visits and zero-inflated negative binomial regression to analyze mental health visits because of the high number of zero counts and overdispersed distribution of mental health visits ( 28 ). Regression coefficients derived from negative binomial models were the log of rate ratios. The rate ratio can also be interpreted as the expected number of visits for patients with PTSD divided by the expected number of visits for patients without PTSD. We used logistic regression for binary dependent variables, such as any inpatient admissions and any antidepressant usage. Regression coefficients from logistic regression models were interpreted as the log of odds of inpatient admission or antidepressant use. The exponentiated regression coefficients provided the odds ratios. Negative binomial regression was used to analyze differences in antidepressant usage among antidepressant users. Statistical analyses were conducted with Stata, versions 9.2 and 10.0.

For cost analyses, we summarized outpatient costs, medication costs, inpatient costs for those with inpatient admissions, and total costs. Generalized linear models with a gamma distribution and a log link were used to account for the nonnormal cost distribution. Data were adjusted for population weights and clinic clustering.

Results

Patient characteristics

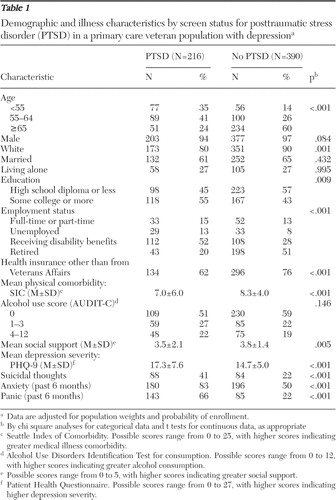

Depressed patients with PTSD were more likely than depressed patients without PTSD to be younger, be nonwhite, have a higher education level, and to receive disability benefits and were less likely to have non-VA health insurance ( Table 1 ). Depressed patients with PTSD also had slightly lower chronic illness comorbidity, less social support, higher depression severity, more frequent suicidal thoughts, and more anxiety and panic attacks.

|

Utilization

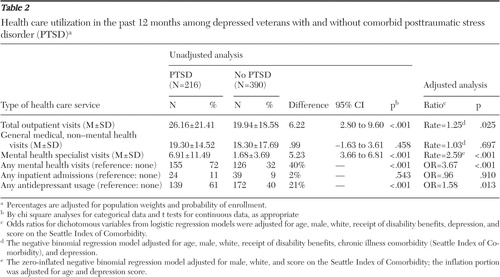

Unadjusted bivariate comparisons of health care utilization by PTSD screen status over 12 months are shown in Table 2 . Compared with patients without PTSD, depressed patients with PTSD had more total outpatient visits (26.16 versus 19.94, p<.001) and more mental health specialty visits over the prior year (6.91 versus 1.68, p<.001). Substantially more depressed patients with PTSD received mental health specialty care at VA clinics (72%) than depressed patients without PTSD (32%) (p<.001). For patients who used VA mental health specialty care, depressed patients with PTSD had a median of six mental health specialty visits over 12 months, compared with a median of four visits for patients without PTSD. A higher proportion of depressed patients with PTSD than those without PTSD were prescribed antidepressants (61% versus 40%, p<.001). We found no significant differences in other service categories.

|

Adjusted utilization rate ratios for depressed patients by PTSD screen status are also shown in Table 2 . Depressed patients with PTSD averaged 25% more outpatient visits and more than twice as many mental health visits than patients without PTSD. Depressed patients with PTSD were also more likely to use antidepressants.

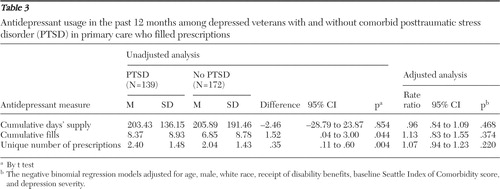

Table 3 presents antidepressant usage data over the past 12 months among antidepressant users by PTSD screen status. Although patients with PTSD had substantially higher rates of antidepressant usage, the average cumulative days' supply, number of cumulative fills, and number of unique prescriptions did not differ significantly between depressed patients with and without PTSD after we adjusted for confounders.

|

Costs

The adjusted and unadjusted costs for comparing depressed patients by PTSD screen status are shown in Table 4 . Cost comparisons were consistent with utilization comparisons, and most adjusted results were consistent with unadjusted findings. After adjustment for confounders, depressed patients with PTSD had significantly higher mean outpatient costs ($1,399 per patient in the past 12 months, p<.001) and higher mean medical care costs ($425, p<.001) than patients without PTSD. Outpatient cost differences were mainly due to additional mean mental health care costs of $1,381 (p<.001) among depressed patients with PTSD. These patients also had higher total medication costs, including higher antidepressant costs.

|

Discussion and conclusions

Similar to previous studies, this study showed that depressed patients with PTSD were much more mentally distressed and had higher health care costs in the past 12 months than depressed patients without PTSD. Depressed patients with PTSD averaged $1,381 higher mental health care costs and about 20% more total health care costs than depressed patients without PTSD in the past 12 months. These additional costs were largely due to more use of outpatient mental health services and antidepressants. These veterans were probably much more distressed and therefore used more services. It is possible that higher use of mental health services led to greater likelihood of screening positive for PTSD; we cannot determine the direction of causality in this cross-sectional study.

Our utilization and cost findings are generally consistent with previous studies indicating that PTSD is associated with increased utilization and costs of health care services ( 7 , 13 , 17 ). This study found that higher utilization and costs were independent of depression severity. Unlike in previous studies, we did not find higher utilization of general medical (non-mental health) services among depressed patients with PTSD (after adjustment for covariates); the majority of the differences in use and costs were concentrated in mental health services and antidepressant use. Our results using administrative data are consistent with patterns of increased outpatient visits for emotional health found by Campbell and colleagues ( 5 ) using self-report WAVES data.

Given the high rates of distress among depressed patients with PTSD, approaches are needed to effectively meet these needs. Although effective depression treatment in primary care has been demonstrated with collaborative care approaches, effective treatment for PTSD in primary care is not well established. Patients with PTSD and depression may require a "stepped care" approach that adds PTSD specialized mental health care or psychotherapy to primary care-based depression treatments. Alternatively, a collaborative care treatment model with a primary care-based mental health care manager may be effective in treating depression and comorbid PTSD ( 29 , 30 ). This approach requires support from a consulting mental health specialist and effective mental health specialty referral for patients not responding to treatment in primary care. Future research should evaluate such stepped-care and collaborative care approaches to treating depression and comorbid PTSD.

Our study has several limitations. Participants were mainly male, white, and adults aged 55 and older. PTSD trauma differs between women and men. Among male veterans, the most common precipitant of PTSD is combat trauma, whereas among women a history of sexual assault and rape are the main traumas ( 31 , 32 ). Our PTSD screening tool and survey did not ask about exposure to combat or other trauma, so we were unable to determine which traumas led to PTSD. Our study did not explore visits for specific physical or medical illnesses in detail. Finally, we used administrative data for costs and health care use, which may have more errors and omissions than data collected specifically for research purposes. However, administrative data are the source necessary for accountability and funding purposes.

Current rates of PTSD among service members from Iraq are reported to be 17%–19% and are expected to rise ( 33 , 34 ). As these war veterans return to the United States and to civilian life, VA and non-VA clinical practices are likely to see increases in needs for mental health care services and should plan and budget for the associated rise in costs. Military health insurers, VA, and other health care systems that treat war veterans should also focus on developing effective clinical and care models to address the needs of this population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The results reported here were from WAVES. The research reported was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (MHI 99-375). The authors recognize Chuan-Fen Liu, Ph.D., M.P.H., for contributing to the conceptual design, guidance in data preparation and review of this study; Lori Zoellner, Ph.D., for her PTSD content expertise; and Ming-Yu Fan, Ph.D., B.S., for her statistical consultation and guidance. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the VA or the University of Washington.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Davidson JR, Stein DJ, Shalev AY, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder: acquisition, recognition, course, and treatment. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 16:135–147, 2004Google Scholar

2. Keane T, Wolfe J: Comorbidity in post-traumatic stress disorder: an analysis of community and clinical studies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 20:1776–1788, 1990Google Scholar

3. Mellman TA, Randolph CA, Brawman-Mintzer O, et al: Phenomenology and course of psychiatric disorders associated with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1568–1574, 1992Google Scholar

4. Southwick SM, Yehuda R, Giller EL Jr: Characterization of depression in war-related posttraumatic stress, disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:179–183, 1991Google Scholar

5. Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu CF, et al: Prevalence of depression-PTSD comorbidity: implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22:711–718, 2007Google Scholar

6. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048–1060, 1995Google Scholar

7. Dobie DJ, Maynard C, Kivlahan DR, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder screening status is associated with increased VA medical and surgical utilization in women. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(suppl 3):S58–S64, 2006Google Scholar

8. Felker BL, Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, et al: Identifying depressed patients with a high risk of comorbid anxiety in primary care. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 5:104–110, 2003Google Scholar

9. Zayfert C, Dums AR, Ferguson RJ, et al: Health functioning impairments associated with posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorders, and depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190:233–240, 2002Google Scholar

10. Oquendo MA, Friend JM, Halberstam B, et al: Association of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression with greater risk for suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:580–582, 2003Google Scholar

11. Blanchard EB, Buckley TC, Hickling EJ, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid major depression: is the correlation an illusion? Journal of Anxiety Disorders 12:21–37, 1998Google Scholar

12. Simon GE: Psychiatric disorder and functional somatic symptoms as predictors of health care use. Psychiatric Medicine 10:49–59, 1992Google Scholar

13. Marshall RP, Jorm AF, Grayson DA, et al: Medical-care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:954–962, 2000Google Scholar

14. Kessler LG, Burns BJ, Shapiro S, et al: Psychiatric diagnoses of medical service users: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. American Journal of Public Health 77:18–24, 1987Google Scholar

15. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al: Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:352–357, 1995Google Scholar

16. Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, et al: The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:427–435, 1999Google Scholar

17. Kulka R, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al: Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, Brunner Mazel, 1990Google Scholar

18. Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Sengupta A, et al: PTSD and utilization of medical treatment services among male Vietnam veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:496–504, 2000Google Scholar

19. Marshall RP, Jorm AF, Grayson DA, et al: Medical-care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:954–962, 2000Google Scholar

20. McFall M, Tackett J, Maciejewski ML, et al: Predicting costs of Veterans Affairs health care in Gulf War veterans with medically unexplained physical symptoms. Military Medicine 170:70–75, 2005Google Scholar

21. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16:606–613, 2001Google Scholar

22. Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al: The Primary Care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry 9:9–14, 2003Google Scholar

23. Fan VS, Au D, Heagerty P, et al: Validation of case-mix measures derived from self-reports of diagnoses and health. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 55:371–380, 2002Google Scholar

24. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al: The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking—Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine 158:1789–1795, 1998Google Scholar

25. Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Felker B, et al: Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in Veterans Affairs primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 18:9–16, 2003Google Scholar

26. Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:212–220, 2000Google Scholar

27. Barnett PG: Review of methods to determine VA health care costs. Medical Care 37:AS9–AS17, 1999Google Scholar

28. Cameron AC, Trivedi PK: Regression Analysis of Count Data. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 1998Google Scholar

29. Hegel MT, Unützer J, Tang L, et al: Impact of comorbid panic and posttraumatic stress disorder on outcomes of collaborative care for late-life depression in primary care. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:48–58, 2005Google Scholar

30. Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, et al: A randomized effectiveness trial of stepped collaborative care for acutely injured trauma survivors. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:498–506, 2004Google Scholar

31. Norris FH: Epidemiology of trauma: frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:409–418, 1992Google Scholar

32. Suris A, Lind L, Kashner TM, et al: Sexual assault in women veterans: an examination of PTSD risk, health care utilization, and cost of care. Psychosomatic Medicine 66:749–756, 2004Google Scholar

33. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351:13–22, 2004Google Scholar

34. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS: Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295:1023–1032, 2006Google Scholar