Socioeconomic Deprivation and Extended Hospitalization in Severe Mental Disorder: A Two-Year Follow-Up Study

Psychiatric admissions are more common in geographic areas of greater socioeconomic deprivation ( 1 ), but it is not clear whether deprivation is also associated with extended hospitalization. If so, the deprivation itself may explain delayed recovery (for instance, poverty may bring about resignation and low self-esteem), or the apparent association may be explained by confounding variables, such as comorbid substance abuse or more severe psychotic symptoms.

Our hypothesis was that greater deprivation at admission would predict total duration of psychiatric hospitalization over the two-year follow-up, even after we controlled for clinical and service factors. To examine our hypothesis, we looked at the socioeconomic levels of small areas of residence ( 2 ) among inpatients from South Auckland, New Zealand. We used deprivation of residence as an individual attribute. We also aimed to explore whether extended stay was related to poor illness recovery or to having no suitable accommodation to be discharged to.

Methods

Compared with most of New Zealand, the South Auckland district (378,000 residents) has a high level of deprivation. For example, in 1996 34% of persons in that district lived in areas ranked nationally as being in the most deprived quintile ( 3 ), and there was a high proportion of ethnic minorities in the district (18% Maori, 17% Pacific Islander, 8% Asian, 58% New Zealand European and other groups). Most residents live in urban areas. Any residents needing secondary mental health care would normally use the free public district mental health service. Private care for severe mental disorders is negligible. In 2000 the district mental health service had 40% to 45% fewer psychiatric beds and community mental health staff than recommended nationally ( 4 ), which can lead to pressure to keep admissions short and to a high workload for staff.

The cohort comprised consecutive admissions from within the district to the psychiatric inpatient unit from June 1998 to December 2000. We excluded admissions of persons who did not live in the district and of those who had no address. We followed each participant for two years from his or her index admission. For a random subsample, made up of consecutive index admissions between November 1999 and August 2000, we collected additional clinical and service-related data within the first 24 hours of the admission by using structured questionnaires, including the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales ( 5 ), the Global Assessment of Functioning ( 6 ), and the Reasons for Admission Schedule ( 7 ). For those from this subsample who were still admitted after five weeks, we collected data by using the Reasons for Continued Stay Schedule ( 8 ). A trained psychiatric research nurse collected these data from clinical case notes and by interview with the primary nurse and consultant psychiatrist.

Interrater reliability of the research nurse's ratings with those of a research psychiatrist (MA) was mostly good. For 35 patients, interrater reliability for 80% of the items on the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales had a mean Cohen's kappa between .61 and .77. For items 8 (other symptoms) and 9 (relationships) the kappas were .55 and .50, respectively. The research psychiatrist (MA) and the research nurse discussed the ratings and repeated the reliability exercise later with 30 additional patients. Interrater reliability for the 30 additional patients showed slightly improved agreement. The Auckland Ethics Committee (now known as the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee) approved the study.

Total length of stay was the total number of days of hospitalization at the district psychiatric inpatient unit for each patient in the 24 months after the date of their index admission.

We measured deprivation with the NZDep96—a deprivation index that was created from 1996 census data ( 9 ). The index was derived from data from small areas (median of 90 persons per small area) by using a weighted combination of the age- and sex-standardized variables. We defined persons as being in the most deprived category if they lived in areas ranked in the lowest quintile (in line with the New Zealand definition of "poor populations"); the moderately deprived category if they lived in areas ranked in the next highest quintile; and in the least deprived category if they lived in areas ranked in the top three quintiles. An independent firm assigned a geographical small-area code to each patient's address at admission, which enabled assignment of the correct deprivation score.

We analyzed the log of total length of stay and the geometric mean, because of the lognormal distribution of the total length of stay. We used generalized linear modeling to model the effect of deprivation in three categories. We calculated an estimate of the days of stay for each category of deprivation with all other variables in the model at baseline by exponentiating the regression coefficients. [Two figures showing the average total length of stay and the log of the average total length of stay, along with calculations for the estimated length of stay, are available as an online supplement to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]. After adding in each potential confounding variable, we carried out a likelihood ratio test to see whether deprivation made an independent contribution to the model.

Results

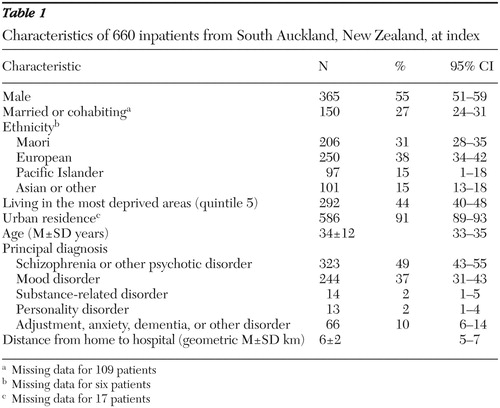

A total of 872 patients from the district were admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit during the study period. We excluded 17 patients because they had no address to code for deprivation. Of the 855 remaining patients, 291 constituted the subsample of admissions between November 1999 and August 2000 for which we had detailed information. Of the other 564 patients in the sample, we were able to include 369 who had enough information about residential address to enable coding at small-area level. Those excluded were slightly more likely to be from an ethnic minority group or unmarried, but these differences were not statistically significant. Table 1 shows characteristics of the total sample (N=660) at index admission.

|

Thirty-eight percent (N=250) of patients in the total sample had one or more readmissions during the two-year follow-up. The median total length of stay was 28 days. Greater duration of stay was associated with more deprivation (F=4.40, df=4 and 655, p=.002), ethnicity (Pacific Islander and Maori ethnicity) (F=6.88, df=3 and 650, p<.001), being unmarried (F=11.10, df=1 and 549, p=.001), and primary diagnosis (schizophrenia and mood disorders) (F=36.15, df=3 and 656, p<.001). The effect of deprivation on duration of stay appeared to be confounded by ethnicity and primary diagnosis, but the effect was still significant after we adjusted for these factors and for age, gender, marital status, and urban residence (likelihood ratio χ2 =10.28, df=2, p=.006). Deprivation did not significantly increase risk of readmission in the study period.

The demographic characteristics and primary diagnosis of patients with additional clinical data did not differ significantly from the full cohort. Twenty-seven percent (N=79) of the subsample had no previous admissions, the rest (N=212, or 73%) had one or more. Median length of mental illness was four years (range, less than one year to 40 years). For the index admission in the study, 48% (N=139) had a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, 91% (N=265) had serious symptoms and impaired reality testing or major impairment in several areas of function, 14% (N=41) had severe aggression or overactivity, 11% (N=32) had severe problem drinking or severe drug abuse, 5% (N=15) had severe physical illness, 26% (N=76) had poor social support, and 68% (N=198) were admitted involuntarily under the New Zealand Mental Health Act. For 48% (N=140) of patients, reinstatement of medication, mostly as a result of nonadherence, was rated as a major reason for admission.

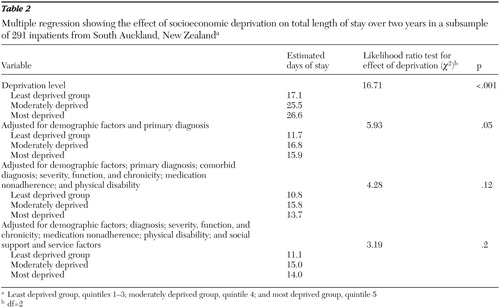

As shown in Table 2 , after adjustment for demographic factors and primary diagnosis, deprivation was associated with a 36% increase in stay, very similar to that for the full sample. After adjustment for a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis, clinical severity, function, and chronicity, the coefficient fell and the effect of deprivation fell below the conventional level of significance. After the social support and service-related factors were added in, the coefficient for the effect of deprivation fell slightly further.

|

For the 96 patients in the subsample who were still admitted after five weeks, their consultants described major contributory reasons for ongoing admission: need for supervision (N=73, or 76%), resistant symptoms (N=61, or 64%), lack of accommodation (N=27, or 28%), risk to others (N=12, or 13%), and medical problems (N=13, or 14%). At that time point, consultants rated only 25% (N=24) as being well enough to be able to be placed outside hospital, most of whom (N=17, or 70%) would have required high-level supported housing.

Discussion and conclusions

We found that lower socioeconomic position, as measured by deprivation of neighborhood of residence, was associated with increased duration of inpatient stay over a two-year period. This relationship held after demographic factors and primary diagnosis were controlled for, but it did not hold after adjustment for comorbidity, chronicity of mental illness, and poor function. This is the first prospective study of total duration of stay and socioeconomic deprivation to control for detailed clinical factors, and it is in contrast to cross-sectional studies and those restricted to the duration of single admissions ( 1 , 10 ).

A potential source of bias was the exclusion of 23% of the sample, because we could not match the recorded address with the New Zealand "Streets" file. Most problems in geocoding are due to errors in spelling and are likely to be related to poor education or illness severity, which in turn are likely to be associated with deprivation—thus we probably excluded more with greater deprivation. Results from the full sample may thus underestimate the effect of deprivation on hospital stay. It may be also that errors about address were related to being in less stable housing, thus we may have excluded more with greater housing difficulties; however, the subsample gives unbiased information because we had complete residential information for this group. We were able to control for most potentially important confounders, although there may be residual confounding because we made ratings from case notes and staff observations rather than direct from users or caregivers.

NZDep96 was developed in line with deprivation theory, and its small-area level has a median of 90 persons, which minimizes measurement error ( 9 ). However, we cannot say whether the effect of deprivation was at the individual, household, or neighborhood level. Future research should include an appropriate sample size of both individuals and areas to develop a multilevel model of recovery in severe mental disorders. Our setting was a deprived urban area with a high proportion of participants who were from indigenous and ethnic minority groups where virtually all residents would use the public mental health system and where the provision of psychiatric services, particularly the number of community mental health staff, was below national benchmarks ( 11 ). Results from our random sample of geographically representative admissions are likely to be generalizable to similar settings in other developed countries.

It is likely that much of the association that we found between deprivation and extended stay was explained by selection, because the effect was no longer significant once we adjusted for severity and chronicity. Selection may also be indirect—for example, operating on determinants of health, such as general cognitive ability and excessive alcohol consumption. Even if deprivation itself is not causative, if people from more deprived areas are likely to have or need longer psychiatric admissions, this has clear public health implications for provision of care in their neighborhoods. It was striking that medication nonadherence was common on admission, often for a long time before admission. It was also striking that most of those remaining in the hospital at five weeks were still ill. Provision of standard housing would not be sufficient to enable such persons to be treated at home.

It will be important to design and test interventions among persons from more deprived areas, who represent a large proportion of those using public mental health services. Randomized controlled trials of supported housing are needed in more deprived populations and to test for interventions for poor treatment adherence ( 12 ) and comorbid substance abuse ( 13 ). Policies are needed to increase resources for more deprived areas that can be used for coordinated evidence-based preventive and treatment services ( 14 ), housing, improved work and schooling ( 15 ), and antistigma interventions.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the Oakley Mental Health Research Foundation and the Auckland Medical Research Foundation for funding and Clare Salmond, M.Sc., and Peter Crampton, Ph.D., for advice on use of NZDep96.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Shepherd G, Beadsmoore A, Moore C, et al: Relation between bed use, social deprivation, and overall bed availability in acute adult psychiatric units, and alternative residential options: a cross sectional survey, one day census data, and staff interviews. British Medical Journal 314:262–266, 1997Google Scholar

2. Salmond C, Crampton P: NZDep96: what does it measure? Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 17:82–100, 2001Google Scholar

3. Jackson G, Palmer C, Lindsay A, et al: Counties Manukau Health Profile. Auckland, New Zealand, Counties Manukau District Health Board, 2001Google Scholar

4. Blueprint for Mental Health Services in New Zealand: How Things Need to Be. Wellington, Mental Health Commission, 1998Google Scholar

5. Amin A, Singh SP, Croudace T, et al: Evaluating the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales: reliability and validity in a three-year follow-up of first-onset psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:399–403, 1999Google Scholar

6. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, revised. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

7. Flannigan CB, Glover G, Feeney ST, et al: Inner London collaborative audit of admissions in two health districts. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:734–742, 1994Google Scholar

8. Abas M, Vanderpyl J, LeProu T, et al: Psychiatric hospitalisation: reasons for admission and alternatives to admission in South Auckland, New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 37:620–625, 2003Google Scholar

9. Salmond C, Crampton P, Sutton F: NZDep91: a New Zealand index of deprivation. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 22:95–97, 1998Google Scholar

10. Abas M, Vanderpyl J, Robinson E, et al: Socio-economic deprivation lengthens hospital stay in severe mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:581–582, 2006Google Scholar

11. Report on Progress 1998–2000 Towards Implementing the Blueprint for Mental Health Services in New Zealand. Wellington, Mental Health Commission, 2001Google Scholar

12. Mukherjee S, Sullivan G, Perry D, et al: Adherence to treatment among economically disadvantaged patients with panic disorder. Psychiatric Services 57:1745–1750, 2006Google Scholar

13. Tracy SW, Trafton JA, Weingardt KR, et al: How are substance use disorders addressed in VA psychiatric and primary care settings? Results of a national survey. Psychiatric Services 58:266–269, 2007Google Scholar

14. Goldman HH: Making progress in mental health policy in conservative times: one step at a time. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:424–427, 2006Google Scholar

15. Cook JA: Employment barriers for persons with psychiatric disabilities: update of a report for the President's commission. Psychiatric Services 57:1391–1405, 2006Google Scholar