Perpetrators of Homicide With Schizophrenia: A National Clinical Survey in England and Wales

There is a weak but definite association between schizophrenia and violence ( 1 , 2 ). Few studies have examined rates of schizophrenia among persons convicted of homicide ( 3 , 4 ). There have, however, been a number of detailed inquiries into the care of individual patients with schizophrenia who have committed homicide ( 5 ). In some cases there has been a long-standing pattern of disrupted contact with mental health services, whereas in others the homicide appears to have occurred soon after illness onset, before the offender had been in contact with services.

This is the first study to examine the clinical care of a large sample of homicide perpetrators with schizophrenia. The aim was to describe the social and clinical characteristics, mental state features, offense details, and outcome in court of a national sample of people with schizophrenia convicted of homicide in England and Wales.

Methods

The study was carried out as part of the National Confidential Inquiry Into Suicide and Homicide by People With Mental Illness ( 6 ), a survey that collects data on all homicides in the United Kingdom, particularly on perpetrators in contact with mental health services.

Data collection had three stages. First, the names of persons convicted between April 1996 and April 1999 of homicide (murder, manslaughter, or infanticide) in England and Wales were given to the Confidential Inquiry survey by the Home Office, which routinely collects this information. Second, psychiatric reports were requested from the courts of trial, the prison service, the Crown Prosecution Service, health services, and other sources. Records of previous offenses were obtained from the Police National Computer. Third, names and identifying details of the perpetrator were submitted to the main hospital and community trust in the perpetrator's district of residence in order to check for past treatment. Neighboring trusts and hospitals cited in psychiatric reports were also contacted. If the perpetrator's address was not known, data were sent to all trusts within the police force area in which the perpetrator had been charged. If the trusts responded that the perpetrator had received treatment in the past, the case was labeled as an "inquiry case." For each inquiry case, the consultant psychiatrist was sent a questionnaire to complete relating to the care and treatment received by the patient. An assessment of the accuracy of hospital checks showed that 97 percent of patients in contact with services in the previous year were detected ( 7 ). The Confidential Inquiry survey has been granted exemption under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001 from obtaining informed consent from patients.

A primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or other delusional disorder (referred to as schizophrenia in this paper) was made either by the psychiatric report writer or by responses to the Confidential Inquiry survey from mental health services.

In a small number of cases in which a discrepancy was found between the diagnosis made in the psychiatric report and that assigned by mental health services, both sources were individually examined by one of the authors (JM). A standardized procedure was used to make the diagnosis on the basis of duration of illness, degree of contact with mental health services, timing of the most recent service contact, identification of symptoms and strength of agreement between psychiatric report writers (in cases with more than one report). The validity of the diagnoses was established by a second author (JS), who independently examined the cases in which there was a discrepancy in the listed diagnosis. Agreement between the two authors was 100 percent.

We rated delusions using a very stringent protocol devised for the study. Extracting data provided in court reports, the protocol rated whether any delusional beliefs made perpetrators frightened or anxious (emotional response to beliefs), whether they sought information to confirm or refute the belief, or whether they changed their conviction in the face of hypothetical contradiction (conviction). Such changes in quality of delusions had been shown in a previous study to relate to acting on delusions ( 8 ). The court reports in homicide cases are written by psychiatrists undertaking a comprehensive review of witness statements and all past medical records, so significant collaborative evidence for the information is often given in the report. Only when there was clear evidence in court reports of a change in the quality of the delusions were these recorded as present. In addition, interrater reliability checks were conducted for 20 percent of cases by two authors (JM and JS), on which there was 100 percent agreement.

The main findings are presented as proportions with 95 percent confidence intervals. If an item of information was not known for a case, the case was removed from the analysis of that item; the denominator in all estimates is therefore the number of valid cases for each item. Subgroup analysis involved the use of chi square tests with statistical significance set at 5 percent.

Results

The Confidential Inquiry survey was notified of 1,594 homicides tried by courts in England and Wales between April 1996 and April 1999. In 15 cases the defendant was found to be unfit to plead or was found to be not guilty by reason of insanity, giving 1,579 homicide convictions. We obtained one or more reports prepared for the court in 1,168 cases (73 percent); 1,155 resulted in convictions, and 13 were found unfit to plead or not guilty by reason of insanity.

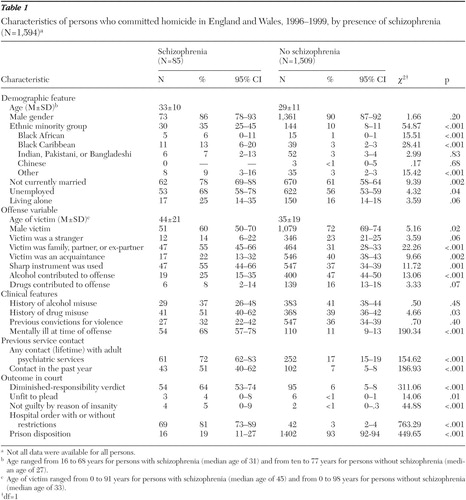

Of the 1,594 perpetrators of homicide tried by courts, 85 had schizophrenia—that is, 5 percent of all homicides in England and Wales during the three-year period. The main demographic, criminological, and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 . A majority were male (86 percent), and one-third (35 percent) were from an ethnic minority group. One-third (32 percent) had been previously convicted for violence. Twelve (14 percent) killed a stranger. More than half had been ill for less than 12 months (32 of 57 persons, or 56 percent). Two-thirds (68 percent) were ill at the time of the offense. Among the 57 persons who were experiencing delusions at the time of the offense, 32 (56 percent) had shown a change in the quality of delusions, including either conviction about or emotional response to their delusional beliefs in the month before the offense.

|

Twenty-four perpetrators (28 percent) never had contact with mental health services. In this group the pattern of illness duration was different from that of the group that had been in contact with mental health services. A larger proportion of perpetrators in the group that never had contact had been ill for more than three years (six of 23 perpetrators, or 26 percent, compared with two of 37 perpetrators, or 5 percent; χ2 =5.84, df=1, p=.04). In the month before the offense, those with no previous service contact were more likely to have experienced an increase in the conviction with which their delusions were held (11 of 21 perpetrators, or 52 percent, compared with nine of 36 perpetrators, or 25 percent; χ2 =4.37, df=1, p=.04).

Eighteen people (21 percent) had previous contact with mental health services that did not occur in the year before the offense. In six cases, mental health services made a diagnosis of schizophrenia—five of these individuals had lost contact with mental health services over time, and another one lost contact because of planned discharge. In the remaining 12 cases, mental health services had not given a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and it is not known whether typical symptoms were absent or undetected at the time of their service contact.

Forty-three people (51 percent) had been in contact with services in the year before the offense; clinical data from questionnaires were available from persons who had been in contact with services in the year before the offense. Of these, only 24 of 40 (60 percent) were under "enhanced CPA" (that is, multidisciplinary community follow-up), 16 of 40 (40 percent) missed their last appointment, and 14 of 36 (39 percent) were noncompliant with treatment in the month before the offense. Twenty-three of 37 people (62 percent) had delusions at the time of the offense. Among those with delusions at the time of the offense, 11 of 18 (61 percent) had experienced a change in the quality of their delusions in the month before the offense. Five of the 11 were noncompliant with treatment, five were out of contact with services, five were not under enhanced CPA (categories were not mutually exclusive). Twenty-five of 43 (58 percent) had a history of violence toward another person that was documented in the case notes.

At court, two-thirds (64 percent) of perpetrators received a diminished-responsibility verdict, the majority were given a hospital order with or without restrictions (81 percent), and 16 (19 percent) were sent to prison ( Table 1 ).

Discussion and conclusions

This is the first study to describe the clinical, service-related, sociodemographic, and criminological characteristics of a national sample of people with schizophrenia who commit homicide. England and Wales have a relatively low homicide rate at 1.8 per 100,000 population compared with the United States, which has a rate of 5.5 per 100,000 ( 9 ). Of the 1,594 people who committed homicide over a three-year period, 85 (5 percent) had schizophrenia. Therefore, the prevalence of schizophrenia among perpetrators convicted of homicide was higher than the prevalence of schizophrenia in the community (.3 to .9 per 1,000) ( 10 ). However, we do not feel that the overrepresentation of people given a diagnosis of schizophrenia and convicted of homicide is due to the low homicide rate.

A quarter of those with schizophrenia had no previous contact with mental health services. Although many of these people had been ill for years, there was evidence of recent clinical deterioration, including a change in the conviction with which their delusional beliefs were held. Of those in recent contact with services, a significant minority were not receiving care under the "enhanced" guidelines provided under the policy titled Care Programme Approach, even when there was a history of violence. Clinical services should ensure that people with severe mental illness and previous convictions for violence receive comprehensive multidisciplinary care, particularly those in the early stage of illness and those who are noncompliant with treatment.

Several main methodological limitations must be highlighted. First, diagnoses were taken from psychiatric reports and from questionnaires. Although consultant psychiatrists completing questionnaires were asked to give ICD-10 diagnoses ( 11 ), psychiatric report writers varied in this respect and therefore there was no standardized method of establishing diagnosis and symptoms. However, in our view, psychiatric reports prepared for court are sufficiently detailed both to make judgments about the presence of symptoms and ICD-10 diagnoses. Second, psychiatric reports were available in only about three-quarters of cases. It is likely that the sample with these reports was biased toward those with serious mental health problems. However, it is also likely that the sample without these reports contained few or no people with schizophrenia. Third, the clinicians providing information may have been biased by awareness of outcome. Fourth, the size of the sample with no previous service contact was too small to allow detailed analysis. Fifth, people with schizophrenia and delusional disorder were categorized together and therefore we were unable to distinguish between them in the analyses. Finally, our ratings of delusions were not based on any standardized assessments. However, they were based on independent reports prepared for the courts, a review of case notes, and witness statements, with a high threshold for inclusion on the basis of clear evidence. We believe that our findings are more likely to represent an underestimate of changes in the quality of delusions.

Delusions are a common symptom present at some stage among about 90 percent of persons with schizophrenia ( 12 ). In a previous study of prisoners awaiting trial ( 13 ), 10 percent were psychotic and 93 percent of these were experiencing delusions at the time of the offense. A direct correlation of experiencing delusions before committing an offense was found in 38 percent of these cases, and furthermore, experiencing delusions was more likely to be linked to violent offenses ( 14 ). In our study, 50 (59 percent) had delusions at the time of the offense and 32 (56 percent) reported a change in the quality of their delusions in the month before the offense. These findings highlight the need for regular assessment of the quality of delusions, with careful monitoring of persons among whom the quality of delusions is changing. Methodologies such as a case-control study could clarify the effectiveness of these interventions.

Acknowledgments

The National Confidential Inquiry Into Suicide and Homicide by People With Mental Illness is funded by the National Patient Safety Agency. The authors acknowledge the help of health authorities, trust and Crown Court contacts, and consultant psychiatrists for completing the questionnaires.

1. Brennan PA, Grekin ER, Vanman EJ: Major mental disorders and crime in the community, in Violence Among the Mentally Ill. Edited by Hodgins S. Dordrecht, Kluwer, 2000Google Scholar

2. Arsenault L, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, et al: Mental disorders and violence in a total birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:979-986, 2000Google Scholar

3. Eronen M, Tiihonen J, Hakola P: Schizophrenia and homicidal behavior. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:83-89, 1996Google Scholar

4. Schanda H, Knecht G, Schreinzer D, et al: Homicide and major mental disorders: a 25 year study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 110:98-107, 2004Google Scholar

5. Ritchie JH, Dick D, Lingham R: The report of the Inquiry Into the Care and Treatment of Christopher Clunis: North East Thames and South East Thames Regional Health Authorities. London, Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1994Google Scholar

6. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, et al: Safer Services: Report of the National Confidential Inquiry Into Suicide and Homicide by People With Mental Illness. London, UK Department of Health, 1999Google Scholar

7. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, et al: Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. British Medical Journal 318:1235-1239, 1999Google Scholar

8. Buchanan A, Reed A, Wessely S, et al: Acting on delusions. II: the phenomenological correlates of acting on delusions. British Journal of Psychiatry 163:77-82, 1993Google Scholar

9. Scottish Executive: Homicide in Scotland 2004/2005. Edinburgh, Statistical Bulletin Criminal Justice Series, 2005Google Scholar

10. Torrey E: Epidemiological comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophrenia Research 39:101-106, 1999Google Scholar

11. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

12. Taylor P: Schizophrenia and violence in abnormal offenders, in Delinquency and the Criminal Justice System. Editors Gunn J, Farrington D. Chichester, United Kingdom, Wiley, 1982Google Scholar

13. Taylor PJ, Gunn J: Violence and psychosis. I: risk of violence among psychotic men. British Medical Journal 288:1945-1949, 1984Google Scholar

14. Taylor PJ: Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. British Journal of Psychiatry 147:491-498, 1985Google Scholar