Increasing the Utilization of Supported Employment ServicesWith the Need for Change Scale

Supported employment services are evidence-based practices that achieve higher rates of employment than alternative approaches among people with psychiatric disabilities ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). Some evidence also indicates that supported employment has long-term positive effects on employment and other quality-of-life variables ( 5 ). However, several reviews have reported that use of these services by people with psychiatric disabilities was low ( 1 , 3 , 4 ).

A 2003 national survey of 3,430 individuals that was conducted by the National Alliance on Mental Illness found that 67 percent of people with psychiatric disabilities were unemployed ( 6 ). A survey comparing care and services received by persons diagnosed as having schizophrenia with recommended care and services found conformance rates for 719 surveyed that were well below 50 percent for psychosocial services in general and 23 percent for vocational services in particular ( 7 ). Another study compared the ratings of 385 consumers and their case managers on the perceived amount of help needed and help received for several support services ( 8 ). The study found only modest correlations between the ratings of the consumers and their case managers on perceived need for and receipt of vocational services.

When family members were added to the consumer-provider dyad, only half of 60 triads (N=180) agreed on outcome and service priorities ( 9 ). Among all pairwise combinations, about a third agreed on outcome and half agreed on service priorities. A qualitative analysis revealed that many practitioners had only minimal experience with employment services and held prejudices against employment services for their consumers ( 10 ). Together these studies indicate that supported employment services are underutilized, and the discrepancy between consumers' and practitioners' assessment of need for vocational services may be a causal factor.

In this study the Need for Change scale was used to assess the felt need for employment among people with psychiatric disabilities who were receiving services from a network of agencies within the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. In addition to responding to the scale, consumers reported whether they would be willing to accept a referral to supported employment services in the succeeding six months. Also, the practitioners who served these same consumers were asked to indicate whether they would refer these consumers to supported employment services in the succeeding six months. The discrepancy between the consumers' and the practitioners' responses that resulted in underreferrals was considered a measure of the potential regional underutilization of supported employment services. People with higher ratings on the Need for Change scale, indicating greater desire for employment, were then referred to local supported employment programs for intake evaluation in order to determine the percentage who were actually admitted.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether consumers' self-reported need for employment was more highly correlated with their decisions to accept supported employment referrals and resulted in more successful referrals to employment services than their practitioners' referral decisions. Multiple regression analysis was used to compare the differential contributions of felt need for employment, age, sex, and duration of unemployment to the variance in the consumers' decisions whether they would accept referrals. The reasons practitioners used to support their referral decisions were compared by logistic regression analysis.

Methods

Setting and participants

During October and November of 2004, one of the five regions constituting the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services initiated an internal quality improvement project. The project was approved by the state and regional directors and by the department's institutional review board. Five case management and residential agencies participated, of which two were state-operated and three were voluntary contract agencies. The 300 service recipients who were enrolled in these five agencies were informed about the project's purpose and gave informed consent. The participating individuals all met the criteria of diagnosis, duration, and disability for persons with serious and persistent mental illnesses. Practitioners were staff members at these five agencies. They provided case management and residential services. They also were directly responsible for assessing the vocational needs of these consumers and for referring them to supported employment services.

Instruments

Need for Change self-rating scale. The Need for Change scale is a self-report version of the practitioner-rated scale contained in the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Readiness Determination instrument ( 11 ). Several recent studies found that this self-report version is a valid summary index of consumers' (235 consumers in one study, 295 in another) felt need for a change in employment status ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). The anchors of this 5-point Likert scale are an urgent need for, a strong need for, not sure of, don't want, and definitely don't want a change in employment status. Associated with each anchor is a brief statement of the degree of satisfaction or dissatisfaction with current employment status and the felt need for a change. Respondents are directed to read all five statements first and then choose the one that best describes their level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction and need for change. Separate scales are provided for those who are employed and those who are unemployed.

Consumers' decision about referral. Respondents were asked if they would accept a referral to employment services and then to choose among three choices: in the next three months, in the next four to six months, not at all in the next six months.

Commitment to Change self-rating scale. A version of the Commitment to Change Scale ( 11 ) asks the consumer to judge each of four statements true or false. The statements deal with beliefs about making changes: belief that a need exists, that a change would be positive, that a change is now possible, and that a change would be supported. Each statement is dichotomously scored as 0 or 1 and can be summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater commitment to change.

Practitioners' referral decision. Practitioners are asked whether they intend to refer a named consumer to employment services and then to choose among the following three responses: in the next three months, in the next four to six months, and not at all in the next six months. Then the practitioner is asked to select among seven reasons (all that apply) as a basis for the decision made for that consumer. The practitioner is also asked to indicate for each reason chosen whether the reason was a positive or negative factor in the referral decision. The listed reasons are the consumer's expressed felt need for a job, current mental status, past clinical history (one to three years), recent work history, past work history (one to three years), recent residential functioning, and recent social functioning.

Procedures

Participating consumers reported their age, sex, and employment status. They also were asked to report the time in years that they were most recently either unemployed or employed, depending on their current employment status. They then completed the Need for Change scale, consumers' referral decision, and the Commitment to Change self-rating. Each agency's quality assurance staff distributed the instruments directly to their agency's consumers. Consumers' responses were not revealed to their practitioners. Each agency's quality assurance staff also distributed the practitioners' referral decision form to the appropriate practitioners, who completed it for each of their participating consumers. Quality assurance staff subsequently made all referrals to the local supported employment programs on the basis of the consumers' Need for Change ratings.

Analyses

Correlations between consumers' Need for Change ratings and their referral decisions were determined. Multiple regression was conducted in which consumers' referral decision was the criterion and the Need for Change rating, Commitment to Change rating, sex, age, and years unemployed were the predictors. The relative contribution of each variable was assessed as a predictor of the consumers' referral decision variance. Because the Need for Change and consumers' referral decision were ordinal scales, optimal scaling techniques ( 15 ) were first used to create interval scale scores for these variables. These quantified scores were then introduced into standard multiple regression equations with a hierarchical entry method, which permitted successive comparisons of the contribution of each predictor.

Correlations between the consumers' referral decisions and their practitioners' referral decisions were also analyzed, and the concordance and discordance between them were evaluated. We used logistic regression to learn the major reasons for practitioners' referral decisions.

In addition all consumers with strong or urgent ratings on the Need for Change scale were referred for intake evaluation at supported employment programs by the quality assurance staff. The percentage of these people who were accepted into the supported employment programs was considered a partial measure of the Need for Change scale's correct prediction rate. This procedure identified false positives but not false negatives. We did not request referral for all participating consumers for two reasons—to prevent subjecting many consumers to an unwanted evaluation and to avoid burdening employment staff with many unnecessary evaluations.

Results

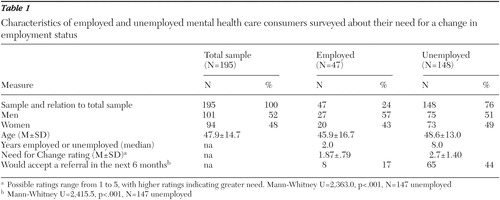

There were 195 participating consumers, who represented 65 percent of the census of the five agencies. The remaining 35 percent refused to participate and did not differ significantly from the participants in sex distribution or employment rate. The employment rate for the entire network was 23 percent. Table 1 describes the characteristics of this study's participants.

|

The baseline rate of employment among the sample was 24 percent, which was similar to that of the network. The employed people differed significantly from the unemployed in their Need for Change ratings and consumer referral decisions. The employed people were more satisfied with their jobs, and only eight wanted a referral to employment services. Among the unemployed, 65 (44 percent) were willing to accept a referral to employment services. This group was relatively older, with a mean age of 48.6 years and a median of eight years of recent unemployment.

Need for Change scale ratings

Of the 148 unemployed people, 147 completed all the study scales. There were 49 (33 percent) who reported a strong or urgent Need for Change rating. All of these 49 people indicated on their consumer referral decision form that they would accept a referral to employment services at some point during the next six months. Another 24 (16 percent) selected the unsure choice on the Need for Change scale. Of these respondents, 12 (50 percent) indicated that they would accept a referral to employment services in the next six months.

Of the remaining 74 people, 35 (24 percent) chose the "don't want to change" rating and 39 (26 percent) chose the "definitely don't want to change" rating. Of these people, four (5 percent) indicated that they would accept a referral to employment services in the next six months. Overall, a Need for Change rating of strong or urgent need for employment achieved a 75 percent sensitivity rating and a 100 percent specificity rating in identifying people who said that they would accept a referral to employment services in the next six months. There were no false positives and 16 (11 percent) false negatives. Overall 131 cases (89 percent) were correctly classified.

The consumers' Need for Change and consumer referral decision ratings achieved a robust .72 bivariate correlation (Kendall's tau, p<.01). However, the consumer referral decision ratings were also significantly correlated with their age (-.29) and years unemployed (-.41). Table 2 reports the results of a multiple regression analysis with optimal scaling and hierarchical entry in which the consumers' referral decision was the criterion. Age and years unemployed accounted for a significant 19 percent of the variance, but the Need for Change scale alone accounted for 47 percent of the variance. Commitment to change alone accounted for almost as much variance as age or years unemployed. In the final model, the Need for Change scale was the dominant factor ( β =.48; partial r=.52) associated with a consumer's decision to accept a referral to employment services in the next six months.

|

Over the subsequent six months, 45 (92 percent) of the 49 people with a strong or urgent Need for Change rating were accepted into the supported employment programs.

Practitioners' referral decisions

There were 30 practitioners who completed the practitioners' referral decision for the 147 unemployed consumers. In the next six months these practitioners intended to refer 32 (22 percent) of these clients to employment services. Of these, five (16 percent) were to be referred in the next three months, and 27 (84 percent) would be referred in the next four to six months. This is in contrast to the 44 percent of the consumers who indicated that they would accept a referral in the next six months. The correlation between the practitioners' referral decisions and the consumers' referral decisions was a modest .17 (Kendall's tau, p=.03).

Among the seven reasons chosen by the practitioners for their referral decisions, clients' current mental status was most frequently chosen (60 percent). The frequency for the other six reasons ranged from 31 percent to 40 percent. The consumer's felt need for employment services was cited in 33 percent of the cases. However, current mental status was not the most influential reason for a consumer's referral. The practitioners' decisions were reclassified as "will refer" or "will not refer" in the next six months. This variable served as the criterion in a logistic regression analysis in which the seven reasons were the predictors. The results of this model were significant ( χ2 =40.5, df=8, p<.001). The model achieved a modest fit (Hosner and Lemeshow χ2 =10.3, df=7, p=.17) and correctly classified 83 percent of the cases. Recent work history and recent residential functioning were the two reasons that significantly affected the odds of the practitioners' decision to refer by a factor of 3 (Wald p<.05) and 5.5 (Wald p<.01), respectively. The observed valences for these two reasons indicated that both had an overall negative impact on practitioners' referrals.

Underutilization and referral method comparisons

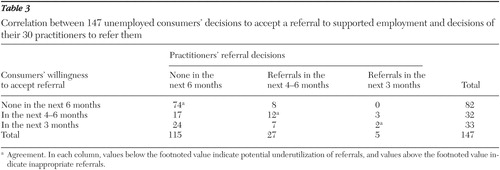

Potential underutilization of employment services was defined as the discrepancy between the decision of the consumers to accept a referral and the decision to refer by the practitioners in the next six months. Table 3 shows the unemployed consumers' referral decisions and their practitioners' referral decisions for comparison.

|

The footnoted values in the matrix (diagonal) reveal the agreement between the consumers and practitioners. In 88 (60 percent) of the cases there was full agreement. Values below the diagonal represent the potential underutilization. In 48 (33 percent) of the cases the consumers expressed a willingness to accept a referral, but the practitioners either would not refer them (28 percent) or would refer them (5 percent) at a slower pace than the consumers indicated. Potential underutilization was at least 28 percent. The values above the diagonal represent the inappropriate referrals. In 11 (7 percent) of the cases the practitioner referred the consumer, but the consumer either did not want a referral (5 percent) or wanted the referral later (2 percent) than offered. There was an inappropriate referral rate of at least 5 percent. When viewed together as a referral strategy, the practitioners' individual referral decisions achieved a sensitivity of 36 percent and a specificity of 75 percent. False positives occurred for 5 percent of decisions, and false negatives occurred for 28 percent of decisions. Overall 67 percent of the cases were correctly classified.

Of the 45 individuals who reported a strong or urgent Need for Change rating and were subsequently accepted into supported employment programs, only ten (22 percent) would have been referred to a supported employment program by the practitioners. In these ten cases, the consumers' expressed felt need for employment was the primary reason given by the practitioners. These practitioners' decisions represented an actual 24 percent underutilization rate for supported employment services.

Discussion

Several studies reported the disagreements between consumers and practitioners in their perceptions of the need for and reception of services. This study revealed the consequences of such disagreements by showing that 24 percent of this sample would have been denied access to supported employment services. This underutilization was avoided because the consumers' Need for Change ratings were substituted for the practitioners' decisions by the quality assurance staff when the actual referrals were made. Consumers' felt need for employment was shown among all other variables in this study to be the most relevant factor affecting the appropriate use of supported employment services. Practitioners infrequently used this type of information. These findings may encourage practitioners to seek and use information about their consumers' felt need for employment.

The Need for Change scale as a measure of consumers' felt need for employment is a simple, brief tool that is inexpensive to administer and easily interpreted. Its use can encourage practitioners to pay more attention to their consumers' felt needs and can guide discussion between practitioners and their consumers about employment. The scale's standardized format and response categories, along with its validity, can be reassuring to practitioners who are less experienced with vocational assessments and services. Aggregating consumers' Need for Change ratings can also provide useful information for utilization review and service planning, as was done in this network.

The Need for Change also may serve as a cognitive support for persons with psychiatric disabilities, many of whom struggle with cognitive deficits. It provides a framework for thinking about an important life choice—employment. The Need for Change may help to clarify and formulate felt needs among those with psychiatric disabilities and assist in decision making.

This study's findings are limited by not assessing the false negatives of the Need for Change scale for the full sample and by the potential bias of a self-selected consumer sample. The applied context of this study prevented all 147 unemployed people from being referred to the local supported employment programs. However, the consumers' referral decision data showed that the scale may have resulted in an estimated 11 percent false-negative rate for the full sample, which was less than half that for the practitioners. Self-selection by consumers may have inflated the percentage of those seeking employment and vocational services. People who were willing to participate in this project also may have been more willing to participate in vocational services. The validity of the Need for Change for the nonparticipants in this study remains to be determined. However, given the scale's simplicity, brevity, and focus on consumer input, more consumers may complete it once it is routinely used in this service network as well as in other clinical and rehabilitation settings.

Conclusions

The Need for Change scale as a measure of consumers' felt need for employment is a valid method for referring consumers to supported employment services. It may help to increase the utilization of supported employment services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating agencies and consumers and acknowledge their initiative, commitment, and cooperation toward enhancing the quality of services offered to people in recovery from major mental illnesses.

1. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: An update on supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:335-344, 1997Google Scholar

2. Drake RE, McHogo GJ, Bebout RR, et al: A randomized clinical trial of supported employment for inner-city patients with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:627-633, 1999Google Scholar

3. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, etal: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313-322, 2001Google Scholar

4. Bond GR: Supported employment: evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:345-359, 2004Google Scholar

5. Salyers MP, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: A ten-year follow-up of a supported employment program. Psychiatric Services 55:302-308, 2004Google Scholar

6. Hall LL, Graf AC, Fitzpatrick MJ, et al: Shattered Lives: Results of a National Survey of NAMI Members Living With Mental Illnesses and Their Families. Arlington, Va, National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2003Google Scholar

7. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11-32, 1998Google Scholar

8. Crane-Ross D, Roth D, Lauber BG: Consumers' and case managers' perceptions of mental health and community support services needs. Community Mental Health Journal 36:161-178, 2000Google Scholar

9. Fischer EP, Shumway M, Owen RR: Priorities of consumers, providers, and family members in the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 53:724-729, 2002Google Scholar

10. Drake RE, Becker DR, Bond GR, et al: A process analysis of integrated and non-integrated approaches to supported employment. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 18:51-58, 2003Google Scholar

11. Anthony WA, Cohen MR, Farkas MD: Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Boston, Boston University, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1990Google Scholar

12. Casper ES: The role of clients' expectations in their rehabilitation service planning. Continuum: Developments in Ambulatory Mental Health Care 3:231-240, 1996Google Scholar

13. Casper ES, Fishbein S: Job satisfaction and job success as moderators of the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:33-42, 2002Google Scholar

14. Casper ES: A self-rating scale for supported employment participants and practitioners. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:151-158, 2003Google Scholar

15. Meulman JJ: Optimal Scaling Methods for Multivariate Categorical Data Analysis. SPSS White Papers. Chicago, SPSS, 2000Google Scholar