Economic Grand Rounds: The Costs of Treating Persons With Depression and Alcoholism Compared With Depression Alone

It is well established that persons with depression are more likely than the general population to suffer from alcoholism (1,2,3). In the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey, among respondents with an episode of major depression in the previous year, 21 percent were also classified as having a diagnosis of alcohol abuse or dependence, compared with 7 percent of the respondents with no evidence of major depression (1). Alcoholics with co-occurring depression may be at greater risk of psychosocial problems, relapse, and suicide (4,5,6,7,8,9). Conversely, heavy drinking may produce or worsen symptoms of depression.

Research among persons with mental illness and comorbid substance abuse has shown that these individuals use more psychiatric and medical care resources than persons with depression alone, including more hospitalizations, longer stays, and higher than average costs (10,11). Few studies have specifically examined the effect of comorbid alcoholism on costs and service use of persons with depression. Fortney and colleagues (12) studied a sample of about 9,000 inpatients in the Department of Veterans Affairs health system with depression only or depression and alcoholism. These authors found that persons with depression and alcoholism had 55 percent more hospital days and 13 percent more visits than those with depression alone.

In this column we provide new data on treatment costs and utilization by persons with depression and alcoholism compared with depression alone.

Methods

Data were from the 1996-2000 MarketScan database, which compiles claims information from private health insurance plans of large employers. Medstat collects and standardizes claims from more than 200 different insurance plans, including Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, preferred provider organizations, health maintenance organizations (HMOs), and point of service plans. The covered individuals include employees, their dependents, and early retirees of companies who participate in the database. In 1999, about 40 large employers participated, and the databases included 4.1 million covered lives.

Depression was indicated by an ICD-9-CM primary and secondary diagnosis (inpatient claims have up to six diagnoses, and outpatient claims have up to five diagnoses). Alcoholism was indicated by the presence of a diagnosis of alcoholism, a claim for an alcoholism detoxification procedure, or a filled prescription for naltrexone or disulfiram. To be classified as having depression, individuals had to have had a diagnosis of depression in 1997. To be classified as having both depression and alcoholism, they had to have had a diagnosis of depression in 1997 and a diagnosis of alcoholism at any point over the subsequent four-year period. A four-year period was used because alcoholism is a chronic condition and is assumed to be present or in remission over the period before and after treatment.

Inpatient and outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment were identified by whether the inpatient or outpatient claim had a mental heath or substance abuse diagnosis. Psychiatric medication claims were distinguished from other medications if the therapeutic class indicated a psychotropic medication, such as antidepressants or antipsychotics. The therapeutic classes were assigned by the Redbook classification system and included opiate antagonists, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, tranquilizers and antipsychotics, stimulants, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, anxiolytics and sedatives-hypnotics, antimanic agents, and miscellaneous CNS (central nervous system) agents.

Patients with a diagnosis of depression and alcoholism were compared with a sample of persons with depression alone, matched on age, gender, and geographic region. Persons enrolled in HMOs were excluded, because HMO claims did not have information about expenditures. To be included, individuals had to have had a 30-day period without a diagnosis of depression or alcoholism, indicating the start of a new episode. Included individuals had to have been enrolled in the data set for at least two years after their initial diagnosis. Outcomes were measured over the two-year period after the diagnosis of depression. Outcome measures included use of mental health and substance abuse services, mental health and substance abuse expenditures, and total medical care expenditures.

Results

The one-year prevalence rates of a diagnosis of depression, alcoholism, and depression and alcoholism were 39.2, 2, and 1 per thousand, respectively. Among persons with depression, only 2.5 percent were identified as having alcoholism.

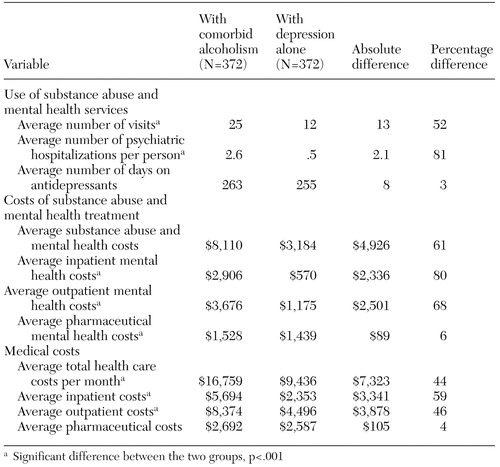

Patients with both depression and alcoholism used substantially more resources than those with depression alone (Table 1). Persons with both diagnoses had twice the number of mental health and substance abuse visits over the two years after their diagnosis and had five times the rate of psychiatric hospitalizations. The length of time that they were prescribed antidepressants did not differ significantly, equaling about one year for both groups.

Consistent with the greater use of inpatient and outpatient mental health and substance abuse services, inpatient and outpatient mental health and substance abuse expenditures were 80 percent and 68 percent higher among patients with alcoholism and depression, respectively, than among those with alcoholism alone. In addition, persons with alcoholism had slightly higher psychiatric pharmaceutical costs (6 percent higher).

Overall, total medical care expenditures for persons with both alcoholism and depression were 44 percent higher ($7,323 greater), on average, than those for persons with depression alone over a two-year period. Total inpatient costs were 59 percent higher ($3,341 greater) for persons with both diagnoses, and total outpatient costs were 46 percent higher ($3,878). No significant difference between the two groups was observed in pharmaceutical costs. The higher total medical care costs were not solely attributable to higher mental health and substance abuse costs, because mental health and substance abuse costs amounted to only about two-thirds the difference in total costs.

Discussion and conclusions

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recently released a major report on co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (13). The report stresses that the vast majority of people with co-occurring substance use disorders and mental disorders do not receive care. For example, preliminary data from the National Comorbidity Survey found that among persons with both substance dependence and serious mental illnesses, only 19 percent received treatment for both disorders, and 29 percent did not receive treatment for either problem. If treatment was provided at all, it was most often for the mental disorder.

The findings reported here are consistent with those of the National Comorbidity Survey, revealing that only 2.5 percent of persons with depression received a diagnosis of alcoholism. Although some persons may receive treatment for alcoholism without having a diagnosis recorded in the claims database, it is unlikely that this is the complete explanation for the extremely low rate of diagnosis of alcoholism relative to the known prevalence of alcoholism among persons with depression.

Failure to adequately address and treat alcoholism among persons with depression has serious implications both for the individual and for the health care system. As the results of this study show, over a two-year period persons with both alcoholism and depression incurred mental health and substance abuse treatment costs that were 61 percent higher and total medical care costs that were 44 percent higher than those of persons with depression alone.

After 20 years of development and research, dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness are emerging as an evidence-based practice (14). Critical components of effective programs include a comprehensive, long-term, staged approach to recovery; assertive outreach; motivational interventions; provision of help to clients in acquiring skills and supports to manage both illnesses and to pursue functional goals; and cultural sensitivity and competence (14). The findings of this study demonstrate the importance of aggressively implementing these approaches among persons with depression and alcoholism.

Acknowledgment

The preparation of this column was supported by grant R01-AA12146-01A1 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Dr. Mark is an associate director at Medstat, 4301 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 330, Washington, D.C. 20008 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Utilization and cost outcomes of patients with both depression and alcoholism and those with depression alone over a two-year period after diagnosis

1. Grant BF, Harford TC: Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 39:197–206, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gilman SE, Abraham HD: A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 63:277–286, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Nelson C, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Keller MB, et al: Prognostic effect of the variable course of alcoholism on the 10-year course of depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:701–706, 1994Link, Google Scholar

5. Aharonovich E, Liu X, Nunes E, et al: Suicide attempts in substance abusers: effects of major depression in relation to substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1600–1602, 2002Link, Google Scholar

6. Cornelius JR, Salloum IM, Day NL, et al: Patterns of suicidality and alcohol use in alcoholics with major depression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 20:1451–1455, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Dhossche DM, Meloukheia AM, Chakravorty S: The association of suicide attempts and comorbid depression and substance abuse in psychiatric consultation patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:281–288, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Pages KP, Russo JE, Roy-Byrne PP, et al: Determinants of suicidal ideation: the role of substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:510–515, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Waller SJ, Lyons JS, Costantini-Ferrando MF: Impact of comorbid affective and alcohol use disorders on suicidal ideation and attempts. Journal of Clinical Psychology 55:585–595, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dickey B, Azeni H: Persons with dual diagnoses of substance abuse and major mental illness: their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 86:973–977, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Garnick DW, Hendricks AM, Drainoni ML, et al: Private-sector coverage of people with dual diagnoses. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:2, 1997Google Scholar

12. Fortney JC, Booth BM, Curran GM, et al: Do patients with alcohol dependence use more services? A comparative analysis with other chronic disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 23:127–133, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Report to Congress on the Prevention and Treatment of Co-Occurring Substance Abuse Disorders and Mental Disorders. Available at www.samhsa.gov/news/cl_congress2002.htmlGoogle Scholar

14. Drake RE, Essock SM, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:469–476, 2001Link, Google Scholar