Economic Grand Rounds: Impact on Cost Estimates of Differences in Reports of Service Use Among Clients, Caseworkers, and Hospital Records

Over the past 30 years, the assertive community treatment model has been widely adopted, but questions have been raised about its cost-effectiveness. Cost-effectiveness studies have used client self-reports, caseworker reports, and hospital records of service use to estimate health care costs. However, the impact of using these different sources to estimate costs has not been examined.

There are potential problems with the consistency of reports from clients and caseworkers (1,2). First, several studies have shown that correlations between client self-reports and caseworker reports can vary, ranging from .21 to .99 for residential status, income, employment, and hospitalizations (1,3,4,5). Second, studies examining hospital service use have demonstrated that clients tend to underreport length of hospitalizations; rates of underreporting have ranged from 4 percent to 38 percent (3,4). Explanations for underreporting include fear of being stigmatized, normal lapses in memory, and cognitive impairments from mental illness (1,2). Factors associated with the severity of cognitive impairments may also influence the ability of clients to recall their use of services. However, the influences of these factors have not been examined. Using different sources of information may result in substantially different cost estimates of service use. However, the potential impact has not been investigated. This study examined correlations between reports of hospital service use by clients and caseworkers and in hospital records and the impact of using these different sources on cost estimates of service use. We focused on hospital services—inpatient and emergency services—because they account for the largest component of costs.

Methods

A convenience sample of 20 clients and their five caseworkers from an assertive community treatment program in Toronto for clients with severe and persistent mental illness were interviewed separately between August and October 2001. Informed consent was obtained by the study coordinator. The project was approved by the research ethics board at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. A single interviewer completed all interviews by using the study questionnaire, which consisted of five questions about inpatient admissions—both the number of admissions and days in the hospital—and the number of emergency department visits over the previous nine months.

The research assistant obtained records through the hospital computerized claims database. The hospital records were used as a comparison group. These records serve as good comparisons for three reasons. First, the clients all lived in the catchment area of the hospital, and thus police and emergency services would bring clients in crisis to this hospital. Second, the hospital had reserved inpatient beds for the clients of the assertive community treatment program, and thus staff would bring clients only to this hospital for services. Third, all admissions are likely to be included in the computerized database because it is used for claims—from a single payer—for both physician fee-for-service costs and other hospital costs. Research on similar claims data from the United States in which a single payer covered the costs of services to a similar client population has demonstrated that such data are reasonably accurate in regard to use of hospital-based psychiatric services, with error rates as low as 4 percent (6).

The cost for an inpatient day and an emergency department visit was calculated from the payer's perspective. Per diem and per episode costs in 2001 Canadian dollars were provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. Average per diem cost of an inpatient admission was $487. Average cost of an emergency department visit for mental health services, including overhead and physician services, was $454.55.

A two-way mixed-effects model was used to calculate pairwise intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) by comparing client self-reports, caseworker reports, and hospital records of service use for the number of inpatient days and emergency department visits. Average costs and cost differences were calculated for both inpatient days and emergency department visits.

The association between education and community functioning and the consistency of reporting was examined. We examined level of education and community functioning because these factors likely reflect clients' cognitive impairments associated with the severity of their mental illness and their current mental status, which in turn may impair recall their of service use. For education, clients were identified as those who completed high school and those who did not. Scores on the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) (7) were used to group patients into two categories: little disability, a score of 63 to 85; and moderate-to-severe disability, 17 to 62. Alternately, the sample was stratified on education and community functioning, and ICCs were calculated for client reports compared with hospital records.

Results

The mean±SD age of the clients was 39.5±9.9 years (range, 22 to 55 years). Fifteen clients (75 percent) were men, and 13 (65 percent) were white. The average educational level was 11th grade (range, fifth grade to four years of postsecondary education). Seventeen clients (85 percent) had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia. The mean score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale was 56.4±15.9 (range, 25 to 84), indicating clinically significant symptoms (8). The mean MCAS score was 57.8±10 (range, 37 to 81).

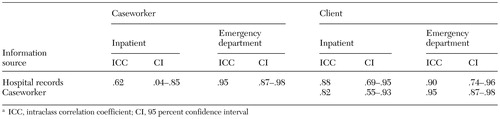

Our analysis found strong correlations between the three data sources. The pairwise ICCs are shown in Table 1. For inpatient days, client self-reports were more closely correlated with hospital records than were caseworker reports. For emergency department visits, both client and caseworker reports were highly correlated with hospital records.

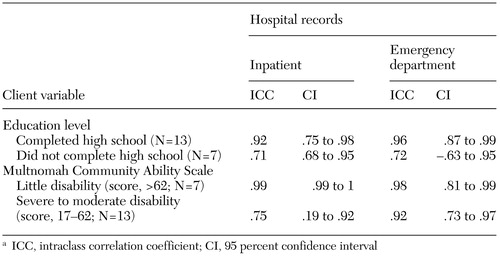

As shown in Table 2, for both inpatient admissions and emergency department visits, the reports of clients who had completed high school were more similar to hospital records than the reports of those who did not complete high school. Similarly, the reports of those in the group with little disability more closely matched hospital records than the reports of those in the other two groups.

We also examined the absolute agreement between the three sources. Agreement rates for inpatient admissions were 95 percent between client self-reports and hospital records, 85 percent between caseworker reports and hospital records, and 90 percent between client and caseworker reports. The respective rates for emergency department visits were 85 percent, 85 percent, and 90 percent.

On the basis of client self-reports, cost estimates for the past nine months were $2,849 (95 percent confidence interval [CI]=$467 to $5,230) for inpatient days and $568 (CI=$-17 to $1,153) for emergency department visits. The cost estimates for inpatient days based on client self-reports and on hospital records were not significantly different (CI=$-1,646 to $1,646). However, for emergency department visits, the estimate based on client self-reports was $136 higher than the estimate based on hospital records (CI=$-180 to $453). The estimated cost for inpatient days based on caseworker reports was $1,948 higher than the estimate based on hospital records (CI=$-1,934 to $5,830). For emergency department visits, the estimate based on caseworker reports was $409 higher than that based on hospital records (CI=$-64 to $882). For the comparison between client and caseworker reports, the estimate based on client reports was $1,948 higher for inpatient days (CI=$-860 to $4,756) and $545 higher for emergency department visits (CI=$-177 to $1,268).

Discussion

The results suggest that clients with severe and persistent mental illness may be a reliable source of information about inpatient admissions and emergency department visits. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating that clients and caseworkers are reasonably consistent in their reports of service use (3,4,5).

Overall, no consistent differences or patterns of differences were found in the reports of clients and caseworkers and in hospital records. However, our results indicate that certain factors, such as educational attainment and functional ability, may influence the consistency of client self-reports. We found that the service use reports of clients who had completed high school and who had a higher level of community functioning were more highly correlated with hospital records than the reports of those who had not completed high school or who were moderately or severely disabled.

The differences in cost estimates that were due to inconsistencies in reporting were substantial, ranging from zero to $1,948 per client over nine months. These inconsistencies could result in a difference of up to 73 percent in the estimated average total cost per client. Differences in cost estimates were largest between caseworker reports and client self-reports and between caseworker reports and hospital records. For inpatient service use, the difference in the estimated cost per client for the nine-month period was a little over $1,900. In a cost study involving a larger number of clients, this inconsistency could make a substantial difference in the evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of this particular service delivery model.

The results suggest that previous cost analyses of assertive community treatment may need to be reexamined in light of this potential distortion. The distortion would be particularly relevant to studies in which service use data were collected from clients with a lower level of educational attainment or community functioning. In future research, we need to further examine and address the differences in cost estimates that may occur when different sources of reporting are used. Possible ways to address this issue include comparing cost estimates based on reports from different sources in order to obtain more reliable cost estimates, attempting to calculate a hybrid estimate based on different sources of reporting, or conducting sensitivity analyses using the different sources.

One limitation of the study is the small sample. Future studies should seek a larger sample to examine the extent to which the variance is affected by sample size. In addition, there may be issues with generalizability of these results. Because this client population has severe and persistent mental illness, they have greater cognitive impairments than other client populations with mental illness, and the discrepancies may not exist for other groups.

Conclusions

This study is a first step toward understanding the potential effects of different reporting sources on cost estimates. The results show that clients, caseworkers, and hospital records generally provide service use information that is closely correlated. Because caseworkers are already overburdened and access to medical records may be costly and difficult, client self-reports may be a reasonable and valid source of information for the purpose of examining service use. However, as our results show, substantial differences in cost estimates may occur when different reporting sources are used. Research should examine factors such as educational level and functional ability that may influence consistency in reporting and circumstances under which substantial distortions in cost estimates may occur even with highly correlated data from different sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Ontario Mental Health Foundation for the Community Mental Health Evaluation Initiative. Dr. Dewa is supported by a Career Scientist Award from the Ontario Ministry of Health. Dr. Cheung is supported by a Health Services Chair Fellowship from the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation/Canadian Institutes of Health Research and by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. The authors thank Paula Goering, Ph.D., R.N., Anthony Levitt, M.D., and May Chin.

The authors are affiliated with the health systems research and consulting unit of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and with the department of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, 33 Russell Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5T 1R8 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Correlations between client reports, caseworker reports, and hospital records of inpatient admissions and emergency department visitsa

a ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; CI, 95 percent confidence interval

|

Table 2. Correlations between client self-reports and hospital records of inpatient admissionsand emergency department visits, by level of education and community functioninga

a ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; CI, 95 percent confidence interval

1. Golding JM, Gongla P, Brownell A: Feasibility of validating survey self-reports of mental health service use. American Journal of Community Psychology 16:39–51, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Clark RE, Ricketts SK, McHugo GJ: Measuring hospital use without claims: a comparison of patient and provider reports. Health Services Research 31:153–168, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

3. Norrish A, North D, Kirkman P, et al: Validity of self-reported hospital admission in a prospective study. American Journal of Epidemiology 140:938–942, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

4. Distefano MK, Pryer MW, Garrison JL: Validity of psychiatric patients' self-reports of rehospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:849–850, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Widlak PA, Greenley JR, McKee D: Validity of case manager reports of clients' functioning in the community: independent living, income, employment, family contact, and problem behaviours. Community Mental Health Journal 28:505–517, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Walkup J, Boyer C, Kellermann S: Reliability of Medicaid claims files for use in psychiatric diagnoses and service delivery. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 27:129–139, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland B, et al: Multnomah Community Ability Scale. Portland, Oregon Health Sciences University, Western Mental Health Research Center, 1993Google Scholar

8. Wirshing D, Marshall B, Green M, et al: Risperidone in treatment-refractory schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1374–1379, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar