Predictors of Residential Independence Among Outpatients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Many outpatients with schizophrenia receive support or supervision in their place of residence, but the predictors of residential independence are not clearly understood. The purpose of this study was to identify factors that predict the degree of residential independence among outpatients with schizophrenia. METHODS: Seventy-two outpatients with schizophrenia were assigned to three groups based on their degree of residential independence. The three groups were compared on three measures of social functioning, on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, and on a battery of neuropsychological tests. RESULTS: Patients' degree of residential independence was related to their frequency of family contact, hygiene skills, relative absence of negative symptoms, and participation in social activities. In a discriminant function analysis, the residential status of 78 percent of the patients was correctly classified. CONCLUSIONS: Aspects of social functioning are significantly associated with patients' independent living status. Future research is needed to determine how family contact, social activities, and hygiene skills may increase patients' degree of residential independence.

Over the last several decades, the care of patients with schizophrenia has largely shifted from the hospital to outpatient settings. However, many of these patients are not able to live on their own in the community but require support or supervision in their place of residence (1). Although a range of residential services has been developed, surveys of psychiatric patients show a consistent preference for living arrangements that are as independent as possible (2,3,4).

Previous studies have found several variables to be associated with the ability of outpatients with schizophrenia to live independently. Younger age (5), female gender (6,7), and a shorter duration of institutional care (8) have been linked with more independent community status.

Neurocognitive abilities have also been implicated in patients' degree of residential independence. Among a group of long-stay hospital patients discharged to the community, patients' skill on a complex reaction-time task predicted their degree of community independence (8). In another study, performance on visual motor and verbal processing tasks was associated with outpatients' residential status (9). Patients' insight about their illness has been associated with whether they received residential supervision (10).

The relationship between patients' daily living skills and their residential status has also been examined. Self-care skills (11) and general functional abilities (5,7) have been associated with patients' independence. An association has not been found between either symptom severity or life satisfaction and degree of independent living (5,8,9).

Relatively few studies have assessed the independent living status of stable outpatients while also obtaining detailed measures of their social and neuropsychological functioning. In the study reported here, we evaluated patients using a battery of neuropsychological tests and assessed their independent living status, symptoms, and social functioning at follow-up two years later. The purpose of the study was to identify factors that determine the degree of residential independence among outpatients with schizophrenia who receive community-based services.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from a public-private mental health system in Baltimore County, Maryland, during the period from July 1993 to June 1995 as part of a study of cognitive deficits and social functioning among outpatients with schizophrenia (12). Exclusionary criteria were current substance abuse, mental retardation, neurological disease, and age younger than 18 years or older than 65 years. All study participants provided informed consent.

The sample comprised 72 subjects, 50 of whom were men (69 percent). Subjects had a mean±SD age of 42.1±9.6 years. Their mean age at onset of illness was 20.9±6.1 years, and they had had a mean of 5.7±4.7 psychiatric hospitalizations. The majority of subjects—59 patients, or 82 percent—were single and had never been married; six patients, or 8 percent, were married; and seven patients, or 10 percent, were separated or divorced. Fifty-seven subjects, or 79 percent, were Caucasian; 14 subjects, or 20 percent, were African American; and one subject was Asian American. The study participants had an average of 13.6±2.1 years of education.

All but one subject was receiving antipsychotic medication at the time of residential assessment. The mean±SD dose in chlorpromazine equivalents was 539±591 mg. Thirty-one patients were receiving atypical antipsychotic medications. Subjects were assessed by their treating doctor as stable in their community functioning for at least one month before the assessment of residential independence, and no subjects had been hospitalized in the two months before the assessment.

Twenty-six patients met diagnostic criteria for schizoaffective disorder. The other patients met criteria for the following subtypes of schizophrenia: paranoid for 19 patients, undifferentiated for 18 patients, residual for seven patients, and disorganized for two patients.

Subjects were classified into three groups based on their degree of residential independence. Group 1, the most independent group, included 14 patients who lived in their own residence without any supervision for at least the previous two months. To quality for this group, patients also had to participate in constructive activity outside of the home for more than 20 hours a week. Among the patients in group 1, seven were competitively employed, five attended a prevocational day program, and two were engaged in volunteer jobs.

Group 3, the most supervised group, included 12 patients who resided in settings such as group homes and highly supervised board-and-care residences where they received direct, on-site supervision for more than six hours a day.

Group 2 included 46 patients whose living arrangements were intermediate between group 1 and group 3. Among group 2 patients, 15 lived with their parents, two lived with other nonspouse extended-family caregivers, 14 lived in apartments with drop-in supervision, 13 lived independently but did not meet the group 1 criterion of daytime activity, and two had moved to their own unsupervised, independent apartment within the previous two months.

Measures and procedures

A battery of neuropsychological tests was administered to all patients at the time of their initial recruitment. The tests included the vocabulary, arithmetic, digit span, block design, digit symbol, and picture arrangement subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-R) (13); the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (14); the Logical Memory test; the Rey-Osterreith Complex Figure Test (15), including the copy and recall test; the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (16); the Trail Making Test (17); the Halstead-Wepman Aphasia Screening Test (18); and the Chicago Word Fluency Test (19).

At two-year follow-up the subjects' symptoms, social functioning, and residential status were assessed. Symptoms were rated using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (20) by raters who showed acceptable interrater reliability on the PANSS symptom factors (r=.88 for the positive symptom factor, .74 for the negative symptom factor, and .82 for the general symptom factor). Subjects were administered the Social Functioning Scale (SFS), which asks about their abilities in seven areas—activation-engagement, interpersonal communication, frequency of activities of daily living, competence at activities of daily living, participation in social activities, participation in recreational activities, and employment or occupational activity (21).

When possible, an informant who lived with or cared for the patient was also interviewed using an informant version of the SFS, and the average ratings were used in the data analysis. Interviews with such informants were available for 38 subjects, or 53 percent.

Patients also were administered the Quality of Life Interview (QOLI), a self-report instrument inquiring about eight life domains—living situation, daily activities, family contact, social relations, legal and safety issues, health, finances, and school or work activities (22). Subjects were also rated by the first author using the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (23); all available information was used in making these ratings. The neuropsychological, symptom, and social functioning measures were selected to provide a comprehensive assessment of patients' functioning in these domains.

Data analysis

Univariate analyses of variance were used to determine the percentage of variance that was shared between patients' residential independence and each study variable. Study variables included demographic characteristics, PANSS factor scores, SFS scores, Multnomah item scores, and QOLI objective scores. Three variables were excluded from these analyses because the ratings were confounded by patients' residential status: the Multnomah scale items about money management and independence in daily life and the SFS employment rating. In addition, gender was not analyzed because it is a dichotomous variable.

Study variables that shared a significant percentage of variance (p<.05) with the residential independence variable were included in a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) (24). The MANOVA was performed to determine the relative contribution of the variables in a discriminant function. We calculated canonical loadings, which are the correlations of each variable with the linear combination of variables in its set; they index the importance of each variable in relation to the residential independence variable. We also derived a classification table from the MANOVA discriminant function. All possible pairwise post hoc contrasts were computed between the residential groups using the Tukey honest significant difference test.

Results

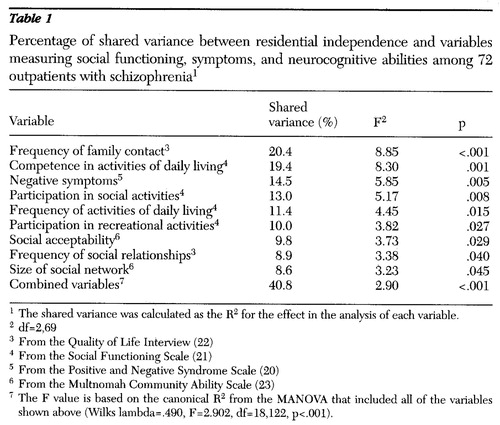

Results of the univariate analyses of variance are shown in Table 1. Nine variables in the univariate analyses shared a significant percentage of variance with the residential independence variable (p<.05), ranging from 20.4 percent for frequency of family contact to 8.6 percent for size of social network. Combined, these variables account for 40.83 percent of the variance in residential independence. On each of these variables, the most independent group had the best functioning and the most supervised group had the most impaired functioning.

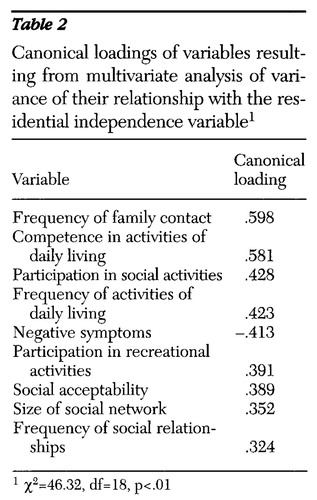

The canonical loadings from the MANOVA discriminant function indicated one significant root, suggesting that only one combination of variables would predict residential independence (χ2=46.32, df=18, p<.001). As Table 2 shows, the root has the highest loadings on frequency of family contact and competence in activities of daily living. The discriminant function analysis correctly classified 78 percent of the patients by residential independence status.

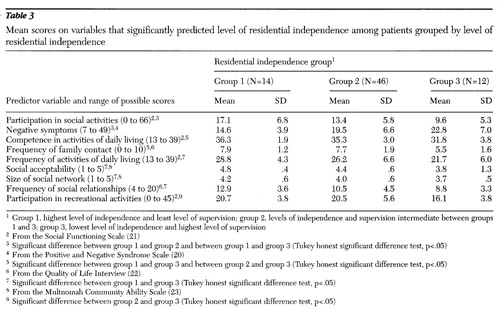

Pairwise contrasts were performed between residential groups on the dependent variables identified in the univariate analyses of variance, which are shown in Table 3. Significant differences between the most supervised and the most independent residential groups were found for eight of the nine variables.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, the degree of residential independence of outpatients with schizophrenia was related to their frequency of family contact, performance of activities of daily living, participation in social and recreational activities and relationships, social presentation, and relative absence of negative symptoms. Combined, these variables accounted for 41 percent of the variance in residential classification within this patient group.

The importance of family contact is consistent with the family advocacy literature describing the support often provided to persons with serious mental illness by their family members (25,26). Data from this study did not identify the process by which family contact is related to patients' residential independence. Families' reaching out to patients may have enabled the patients to function more successfully, or healthier patients may have been able to maintain contact with their families more readily than less healthy patients.

The importance of activities of daily living in patients' residential independence has also been found in previous studies involving patients from different types of settings (5,11). The contribution of activities of daily living to patients' residential status within an outpatient sample highlights the importance of basic care skills in patients' ability to manage successfully on their own.

Unlike two previous studies (8,9), our study did not identify any neurocognitive variables that predicted patients' residential status. This negative finding is noteworthy because subjects received an extensive neuropsychological assessment, the results of which showed that the cognitive impairments of the study patients, as a group, were comparable to those of other samples of outpatients with schizophrenia (12).

Although negative symptoms predicted residential status, positive symptoms did not. Our data are consistent with those of previous studies showing the lack of a significant relationship between the social functioning of patients and their residual positive psychotic symptoms (27,28,29).

The limitations of this study include the cross-sectional nature of the analysis, which makes it difficult to determine cause-effect relationships among the variables. Other limitations include the use of multiple comparisons in the univariate analyses, the relatively small number of patients who were classified in the most independent and supervised groups, and the heterogeneity of the intermediate residential group.

Residential placement is a complex phenomenon that is related to the treatment system and its ability to impose residential placements, as well as to patients' housing needs (30,31). Although other populations and settings may be different from those in our study, we believe our findings are generalizable to outpatients with schizophrenia who are relatively stable; who are without comorbid substance abuse, mental retardation, or neurological disorders; and who reside in suburban communities that provide a range of residential alternatives for persons with serious mental illness.

The future of residential rehabilitation services is uncertain in a managed care environment (32). Better identification of patients who can live independently and of those who require more intensive supervision may help in planning rehabilitation services. Results from this study suggest that frequency of family contact and performance of activities of daily living are highly associated with patients' residential status. Additional research is needed to better understand how these factors may contribute to the ability of patients to live independently.

The authors are affiliated with the Sheppard Pratt Health System, 6501 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21204 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy held November 13-16, 1997, in Miami.

|

Table 1. Percentage of shared variance between residential independence and variables measuring social functioning, symptoms, and neurocognitive abilities among 72 outpatients with schizophrenia1

1 The shared variance was calculated as the R2 for the effect in the analysis of each variable.

2 df=2,69

3 From the Quality of Life Interview (22)

4 From the Social Functioning Scale (21)

5 From the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (20)

6 From the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (23)

7 The F value is based on the canonical R2 from the MANOVA that included all of the variables shown above (Wilks lambda=.490, F=2.902, df=18,122, p<.001).

|

Table 2. Canonical loadings of variables resulting from multivariate analysis of variance of their relationship with the residential independence variable1

1 χ2=46.32, df=18, p<.01

|

Table 3. Mean scores on variables that significantly predicted level of residential independence among patients grouped by level of residential independence

1 Group 1, highest level of independence and least level of supervision; group 2, levels of independence and supervision intermediate between groups 1 and 3; group 3, lowest level of independence and highest level of supervision

2 From the Social Functioning Scale (21)

3 Significant difference between group 1 and group 2 and between group 1 and group 3 (Tukey honest significant difference test, p<.05)

4 From the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (20)

5 Significant difference between group 1 and group 3 and between group 2 and group 3 (Tukey honest significant difference test, p<.05)

6 From the Quality of Life Interview (22)

7 Significant difference between group 1 and group 3 (Tukey honest significant difference test, p<.05)

8 From the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (23)

9 Significant difference between group 2 and group 3 (Tukey honest significant difference test, p<.05)

1. Lamb HR: Treating the Long-Term Mentally Ill: Beyond Deinstitutionalization. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1982Google Scholar

2. Owen C, Rutherford V, Jones M, et al: Housing accommodation preferences of persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 47:628-632, 1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Minsky S, Riesser GG, Duffy M: The eye of the beholder: housing preferences of inpatients and their treatment teams. Psychiatric Services 46:173-176, 1995Link, Google Scholar

4. Tanzman B: An overview of surveys of mental health consumers' preferences for housing and support services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:450-455, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Arns PG, Linney JA: Relating functional skills of severely mentally ill clients to subjective and social benefits. Psychiatric Services 46:260-265, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Andia AM, Zisook S, Heaton RK, et al: Gender differences in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:522-528, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cook JA: Independent community living among women with severe mental illness: a comparison with outcomes among men. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:362-373, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Wykes T, Dunn G: Cognitive deficits and the prediction of rehabilitation success in a chronic psychiatric group. Psychological Medicine 22:389-398, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Brekke JS, Raine A, Ansel M, et al: Neuropsychological and psychophysiological correlates of psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:19-28, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Ringel N, et al: Lack of insight among outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 48:195-199, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Sood S, Baker M, Bledin K: Social and living skills of new long-stay hospital patients and new long-term community patients: Psychiatric Services 47:619-622, 1996Google Scholar

12. Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Ringel N, et al: Neurocognitive and social functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 21:75-83, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wechsler D: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Cleveland, Psychological Corp, 1981Google Scholar

14. Wechsler D: WMS-R, Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. New York, Harcourt Brace Janovich, 1987Google Scholar

15. Rey A: L'examen clinique psychologique dans les cas d'encephalopathie traumatique. [Clinical psychological testing in cases of traumatic encephalopathy.] Archives Psychologique 28:286-340, 1941Google Scholar

16. Heaton RK: Wisconsin Card Sorting Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1981Google Scholar

17. Reitan RM: Manual for Administration of Neuropsychological Test Batteries for Adults and Children. Tucson, Ariz, Ralph Reitan, 1979Google Scholar

18. Halstead WC, Wepman JM: The Halstead-Wepman Aphasia Screening Test. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disabilities 14:9-15, 1959Google Scholar

19. Thurstone LL, Thurstone TG: The Chicago Tests of Primary Mental Abilities. Chicago, Science Research Associates, 1943Google Scholar

20. Kay SR: Positive and Negative Syndromes in Schizophrenia: Assessment and Research. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1991Google Scholar

21. Birchwood M, Smith J, Cockrane R, et al: The Social Functioning Scale: the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:853-859, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH: A community ability scale for chronically mentally ill consumers, part I: reliability and validity. Community Mental Health Journal 30:363-379, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Statistica Volume I: General Conventions and Statistics I. Tulsa, Ok, StatSoft, 1995Google Scholar

25. Hatfield AB, Lefley HP (eds): Families of the Mentally Ill: Coping and Adaptation. New York, Guilford, 1987Google Scholar

26. Tessler R, Gamache G: Continuity of care, residence, and family burden in Ohio. Milbank Quarterly 72:149-169, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. DeJong A, Giel R, Sloof CJ, et al: Relationship between symptomatology and social disability. Social Psychiatry 21:200-205, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Dickerson F, Boronow JJ, Ringel N, et al: Neurocognitive deficits and social functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 21:75-83, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Prudo R, Monroe Blum H: Five-year outcome and prognosis in schizophrenia: a report from the London field centre of the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 150:345-354, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Carling PJ: Major mental illness, housing, and supports: the promise of community integration. American Psychologist 8:969-975, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Cook JA, Jonikas JA: Outcomes of psychiatric rehabilitation service delivery. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 71:33-47, 1996Google Scholar

32. Hollingsworth MS, Sweeney JK: Mental health expenditures for services for people with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 48:485-490, 1997Link, Google Scholar