Use of Psychiatrists, Psychologists, and Master's-Level Therapists in Managed Behavioral Health Care Carve-Out Plans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Outpatient claims data from a managed behavioral health company for 1996 were examined to determine the extent to which patients received services from different types of mental health care providers. METHODS: Claims data for 1996 were obtained from 75 plans with more than 600,000 members that were managed by one behavioral health care organization. Data were examined by type of provider and diagnosis. RESULTS: A total of 349,686 claims were examined. Doctoral-level psychologists accounted for most claims (33.4 percent), followed by psychiatrists (30.5 percent), social workers (19.8 percent), and other master's-level therapists (13.8 percent). Ninety-five percent of patients with a psychotic disorder and 86.2 percent of individuals with bipolar disorder were seen either by a psychiatrist alone or by a psychiatrist in combination with another provider. Among depressed patients, 62.9 percent were seen by a psychiatrist, alone or in combination with another provider. Only 23 percent of patients with an adjustment disorder and 14.1 percent of those with a V-code diagnosis were treated by a psychiatrist, alone or in combination with another provider. Because psychiatrists treated sicker patients, their proportion of patients treated (24.7 percent) was smaller than their proportion of all claims filed. Most patients (78.9 percent) saw only one type of provider. CONCLUSIONS: The results allay concerns that managed care shifts patients away from psychiatrists to doctoral-level psychologists and less expensive providers. The majority of patients with depressive disorders and almost all patients with psychotic disorders had contact with a psychiatrist.

The dramatic growth of managed care in recent years has led to concerns that patients with mental health problems are shifted away from psychiatrists to doctoral-level psychologists or to master's-level therapists. The Medical Outcomes Study found that among depressed outpatients under prepaid managed care in 1986 to 1990, only one in ten received care by a psychiatrist, compared with one in five depressed outpatients insured under an indemnity plan (1,2). Even when the Medical Outcomes Study analysis was limited to patients in mental health specialty settings, only a third of patients with a depressive disorder in prepaid managed care received regular care by a psychiatrist, a rate about half the rate for such patients in traditional indemnity plans (2).

Shifting patients away from psychiatrists may affect both costs and health outcomes. It has been found that treatment by psychiatrists is three times more expensive than treatment by primary care clinicians for comparable patients (2). However, the quality of care, as measured by appropriate antidepressant medication or any type of counseling for depression, has been found to be significantly higher when provided by psychiatrists (3). The costs and quality of care for depression among mental health specialists other than psychiatrists have been found to be intermediate (3).

In a recent study, Goldman and associates (4) reported that the provision of care solely by a psychiatrist or by comanagement with other providers also affects costs and utilization. This finding is more important for patients with disorders that require medication because there is little evidence that the effectiveness of psychotherapy differs by provider type.

The mental health care system has undergone a dramatic change since the Medical Outcomes Study of 1986 to 1990. Unmanaged indemnity insurance for mental health has almost completely disappeared. Instead, a new form of mental health care delivery, by managed care organizations that specialize in administering mental health and substance abuse benefits, has emerged and now dominates the market for private-sector insurance, covering more than 150 million Americans (5). These managed behavioral health organizations are also known as carve-outs because they manage benefits that are carved out from a comprehensive medical plan. They use managed care techniques, such as concurrent utilization review by clinical care managers, best-practice guidelines, and disease management systems, that are significant advancements over the simple gatekeeping arrangements or contractual financial incentives (subcapitation) used in other areas of managed medicine.

A potential advantage of managed care arrangements is that they might target resources to sicker patients more effectively. In the traditional fee-for-service system, care was largely determined by patient demand. Because wealthier patients could more easily afford higher copayments, they were more likely to demand specialty care than patients who had similar illnesses but could not afford such care. The Rand health insurance experiment (6) and the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (7) failed to find a significant link between the types of illnesses patients reported and the specialty of the provider from whom they received care. Because both studies were conducted before widespread use of managed care, absence of such a link suggests that factors other than patients' objective medical needs were influencing their choice of provider.

The Medical Outcomes Study, based on data collected from 1986 to 1990, found that more severely depressed patients were more likely to be treated by psychiatrists, but no evidence was found that prepaid care targeted these patients any better than fee-for-service care (1). At the time of that study, prepaid care primarily meant staff-model and group-model health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and independent practice associations; mental health care was not yet carved out to managed behavioral health care organizations. Thus an important factor determining efficiency and quality of care is whether the new carve-out systems have advantages in matching patients' needs with providers who have the appropriate qualifications.

One major change in carve-out systems is that patients are referred to specialty providers after calling an 800 number; primary care gatekeeping, which was prevalent in traditional HMOs, is not a widely used strategy under carve-out arrangements. Although primary care clinicians no longer have the responsibility for patients seeking treatment for mental illness, they are also no longer reimbursed for treating mental health problems. As a consequence, few primary care claims for such treatment are filed, and most are filed for emergency care. In the past many patients with depressive disorders were seen exclusively in primary care; however, the majority of them did not receive treatment specific to depression (1,2). It is not clear to what extent those patients are shifting to specialty care under carve-outs or remain undertreated in primary care.

Research on the new mental health and substance abuse treatment environment has not kept up with market changes. Data from carve-outs are just emerging, primarily with a cost focus. Employers switching from indemnity to carve-out mental health care have experienced dramatically lower costs, primarily because patients have been shifted from inpatient to outpatient care, the number of authorized visits has been reduced, and providers are reimbursed at lower rates per visit or inpatient day (8,9).

A similar trend has been found in Massachusetts Medicaid data (10). Studies have shown that utilization rates for any mental health specialty care commonly increase under behavioral health carve-out plans (9,11), which could be a consequence of shifting patients with mental health problems from primary to specialty care or of expanding benefits for mental health care, which generally occurs when carve-out plans are adopted. Little is known about provider specialty, quality of care, or outcomes under these new insurance arrangements.

This paper reports initial data on the use of different types of outpatient providers in 75 plans that were managed by one behavioral health company. Current utilization patterns are compared with those from ten years ago in other mental health care delivery systems. The central research questions are, How do carve-out plans use different types of providers? Do most patients see one type of provider, and do patients with different diagnoses see different types of providers?

Methods

This study used 1996 outpatient claims data from 75 employer-sponsored plans with at least 1,000 members that carved out behavioral health benefits. The mental health and substance abuse benefits were administered by one managed behavioral health company, United Behavioral Health (UBH). UBH is the third largest behavioral health organization in the country, managing mental health and chemical dependency benefits for more than 11 million people nationwide.

UBH administers plans that cover only authorized care through network providers—exclusive provider organizations—and plans offering point-of-service options. The point-of-service option, usually restricted to outpatient care, allows unmanaged out-of-network care, but at a cost to the patient that is 20 to 50 percent higher than the cost of care via authorized and concurrently managed services with a network provider (12).

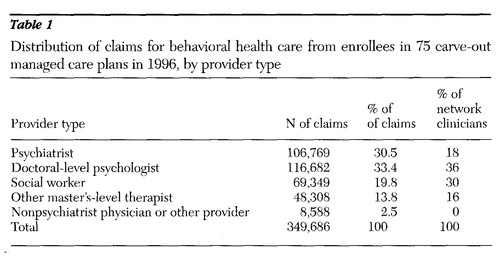

UBH relies completely on contracted independent providers and fee-for-service payments. It does not use capitation (that is, it does not put the provider at financial risk for treatment costs) and does not employ any provider, although such arrangements exist in the industry. The UBH network is made up of 35,000 mental health specialists—18 percent psychiatrists, 36 percent doctoral-level clinical psychologists, 30 percent clinical social workers, and 16 percent other master's-level counselors—and more than 1,600 facilities. However, the proportion of clinicians from various disciplines in the network does not necessarily reflect the use of different types of provider because many network clinicians receive very few referrals. Thus the proportion of care delivered by network psychiatrists could be substantially lower (or higher) than 18 percent.

Mental health specialists must meet minimal qualifications for acceptance into the UBH network: they must be licensed to practice independently by the state in which they practice, be members in good standing in the professional community, and have five years of experience after receiving their license. Approximately 85 percent of clinicians work independently, and the remaining clinicians are affiliated with group practices or facilities. Payments for services are based on national rates and depend on the provider's license. UBH reimbursement rates do not differ by geographic region.

Among the 75 plans, 19 (25 percent) are integrated with an employee assistance program (EAP), and EAP utilization is included in the data reported here. Inclusion of EAPs could reduce the rate of use of psychiatrists because EAP services are generally not delivered by psychiatrists. However, EAP plans that are integrated with mental health care management may refer patients directly to psychiatrists when clinical indicators are evident to the intake coordinators.

The plans in this sample may not cover all employees of all employers because employers continue to offer multiple plans, including HMOs, not necessarily managed by UBH. This factor makes the sample more representative of the average carve-out plan and is useful for describing the current system. Although the 75 plans are a convenience sample, selected because of data availability, we were assured that these plans do not differ in significant ways from other plans administered by UBH.

Results

A total of 349,686 claims for mental health care for members of the 75 plans in 1996 were analyzed. Table 1 presents the distribution of outpatient claims by type of provider. Overall, the largest proportions of claims were filed by doctoral-level psychologists (33.4 percent) and psychiatrists (30.5 percent). Social workers accounted for 19.8 percent of the claims, while other master's-level therapists accounted for 13.8 percent of the claims. Thus the proportion of claims accounted for by psychiatrists was substantially larger than the proportion of psychiatrists in the network—18 percent. Nonpsychiatrist physicians, nurses, and other providers accounted for only 2.5 percent of the claims; these claims primarily reflect use of providers not in the network, including emergency services.

The enrollees in these 75 plans did not belong to any other plan that covered claims for behavioral health diagnoses. This situation represents a dramatic shift away from HMOs, which relied on primary care providers to deliver many types of specialty care, even mental health care. Primary care clinicians may continue to provide some mental health care for patients in the 75 plans, but the associated claims would not list a mental health diagnosis.

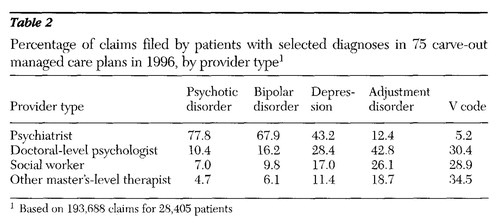

Table 2 shows the distribution of claims for care of patients with selected diagnoses by provider type at the claim level. The diagnoses range from more severe disorders, such as psychotic disorders, to less severe disorders, such as V-code diagnoses (relational problems). The list is not exhaustive and accounts for about two-thirds of all claims; data for claims for patients with other disorders were omitted from this analysis. The data seem to indicate that sicker patients were cared for by psychiatrists. Psychiatrists accounted for nearly 78 percent of the claims for patients with psychotic disorders and 70 percent of the claims for patients with bipolar disorder; psychiatrists accounted for 12 percent of the claims for patients with adjustment disorders and only 5 percent of the claims for patients with V-code diagnoses.

In contrast, master's-level therapists and social workers tended to care for patients with less severe problems, such as adjustment disorders and relational problems. Doctoral-level psychologists seemed to fall in between, dealing with just under 30 percent of the claims for depressive disorders, approximately 43 percent of the claims involving adjustment disorders, and 30 percent of the V-code claims.

The analysis described above was at the claim level rather than the patient level. Approaching the data at the claim level gives providers with a large number of claims per patient a larger share of the total claims. Thus it is not clear how examining the data at the patient level would change the results. Psychiatrists may provide more assessments or medication management, and therefore they may have many patients, which is probably the case when care is comanaged by psychiatrists and other providers.

The data in Table 2 reflect claims by 28,405 patients. These claims were analyzed at the patient level. Most patients (78.9 percent) saw only one type of provider. The results indicated that nearly 94 percent of psychotic patients saw a psychiatrist, either a psychiatrist alone (67.4 percent) or in combination with one of the other provider types (26.2 percent). Similarly, 86.2 percent of the patients with bipolar disorder saw a psychiatrist, either alone (54.2 percent) or in combination with another provider type (32 percent). For those with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, 62.9 percent saw a psychiatrist, either alone (25.1 percent) or in combination with another provider (37.8 percent).

In contrast, individuals with claims for adjustment disorders and V-code diagnoses were much less likely to see a psychiatrist alone (6.5 percent for adjustment disorders and 2.9 percent for V codes). They were less likely to see a psychiatrist in combination with another provider (16.6 percent for adjustment disorders and 11.2 percent for V codes).

Among patients with more than one of the diagnoses listed in Table 2, 76.5 percent saw a psychiatrist in combination with one of the other providers, and 11.1 percent saw a psychiatrist alone. Approximately 6 percent of patients with more than one diagnosis saw a psychologist, 3 percent saw a master's-level therapist, and 3.3 percent saw a social worker.

It is difficult to comment on the association between provider type and having more than one diagnosis. Such patients may have more claims because they are sicker. However, having several diagnoses could also be an artifact of seeing multiple providers with different training and assessment styles.

Finally, this study attempted to estimate how care patterns may have changed by comparing the proportions of depressed patients treated by psychiatrists in 1996 in the 75 carve-out plans in this study and in managed care plans as estimated by the 1986-1990 Medical Outcomes Study (2). The comparison cannot be exact because the design of this study, which used provider-assigned diagnoses, differs from that of the Medical Outcomes Study, which relied on independent assessments by the study team. In addition, we determined the provider's specialty based on submitted claims, whereas the Medical Outcomes Study based the specialty on the type of office in which the patient was sampled. Finally, the number of patients with major depressive disorder or dysthymic disorder receiving mental health specialty care in the Medical Outcomes Study was quite small (N=130), and thus the estimates are less precise than estimates based on large samples. For this comparison, we included only patients in the Medical Outcomes Study who were treated by a mental health specialist.

In the 75 carve-out plans, 78 percent of patients diagnosed as having a major depressive disorder in 1996 saw a psychiatrist. In the Medical Outcomes Study, 29 percent of patients with a major depressive disorder in the prepaid plans saw a psychiatrist (z=6.8, p<.01) and 66 percent in the fee-for-service plans did so (z=2.06, p<.05). Of the patients in our study diagnosed as having dysthymia, 47 percent saw a psychiatrist, compared with 60 percent of patients in prepaid plans in the 1986-1990 study, which was not a significant difference, and 69 percent in fee-for service plans in the previous study (z=2.3, p<.05). However, given the different study designs, the statistical tests may not be very meaningful.

Discussion

This paper provides a first look at how a carve-out managed behavioral health care organization uses different types of providers. Contrary to common beliefs, it does not appear that patients with more severe types of disorders are shifted away from psychiatrists to doctoral-level psychologists and less expensive master's-level therapists and social workers. Psychiatrists and doctoral-level psychologists accounted for the greatest proportion of claims, and psychiatrists were involved in the care of most patients with more severe disorders.

Although there is little evidence that the effectiveness of psychotherapy differs by provider type, studies summarized by Wells and associates (2) have indicated that patients treated by psychiatrists experience higher quality of care for depression, primarily in terms of medication management, which results in better functional outcomes. Of course, the higher quality of care partly reflects the difficulties that nonphysicians have in coordinating care with physicians prescribing medication.

In our study 94 percent of patients with a psychotic disorder and 86 percent of patients with bipolar disorder had some contact with a psychiatrist. However, we wonder what happened to the other patients in these diagnostic groups. Further research is needed to see whether they dropped out of the system and refused to receive care or whether problems exist in the referral system. Referrals and continuity of care might be improved for some patients through outreach efforts.

Several issues still need to be addressed. We have not studied the amount or content of care delivered by each of the provider types. Such a study could be particularly important for individuals whose care is comanaged by psychiatrists and other providers, because recent research has shown that costs and utilization patterns differ between depressed patients seen only by a psychiatrist and those in comanaged care (4). Comanagement has been thought to be most cost-effective when psychiatrists, who bill at the highest rate, are primarily responsible for assessments and medication management, and less expensive providers conduct counseling and other more time-consuming treatments. However, research by Goldman and his colleagues (4) did not support this hypothesis.

In addition, our study did not include claims for psychosocial support services, whose importance for persons with the most severe and disabling mental disorders is well established. These services are usually facility claims and are not related to a specific provider type. Services such as day treatment, residential care, and services in halfway houses are covered in the 75 carve-out plans, and they are used for the most severely ill patients. However, it is important to keep in mind that private insurance does not cover the same range of services that is available in the public sector. For example, social rehabilitation is not covered by private insurance.

We compared our findings for depressed patients with results from the Medical Outcomes Study, which described care patterns ten years ago. Patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder in the carve-out plans in our study appeared to be significantly more likely to receive care from a psychiatrist than patients in prepaid care plans ten years ago. However, individuals with a diagnosis of dysthymia in our study were less likely to receive care from a psychiatrist than those in the earlier study. Unfortunately, differences in the study designs make it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

One limitation of this study is that diagnoses were assigned by the provider, and diagnoses may differ based on providers' training, assessments, or practice. Nonphysicians might tend to make diagnoses of lesser severity—for example, they might diagnose an adjustment disorder in a patient with major depression. This tendency could create a small bias in our results. However, the intensive utilization review that penalizes inconsistencies between diagnoses, processes of care, and treatment plans by denying payment is likely to lead to more reliable diagnoses than are made in traditional insurance systems. A previous study using data from United Behavioral Health found a high correlation between type of treatment and diagnoses (13).

A more important limitation concerns whether the makeup of the provider network and the division of labor are unique to the managed care organization that provided the data or whether these features are more pervasive trends in the industry. Overall, carve-outs certainly operate in very similar ways. Nevertheless, subtler differences could exist in how referrals are made and in how the network is created. Studies like this one could have some selection bias because companies that are able and willing to participate in such research efforts differ in at least this dimension from other companies. Unfortunately, we cannot answer this question because we have not yet been able to obtain similar data from other companies, although we have established agreements to receive such data.

Conclusions

Although concerns have been raised that managed care shifts patients away from psychiatrists, we found that the majority of patients in our study with depressive disorders—and almost all patients with psychotic disorders—had contact with a psychiatrist. The levels of care from psychiatrists for patients in these diagnostic categories may be higher now than under managed care ten years ago. However, it should be noted that only a minority of the patients in our study were treated by psychiatrists.

Our findings suggest that matching patients' needs with providers' qualifications has improved. Whether this improvement signals a more pervasive trend in behavioral health care or whether it is unique to the organization studied remains an open question.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joyce McCulloch, M.S., for help with data analysis and William Goldman, M.D., for comments on drafts of this paper. The data were made available by United Behavioral Health. This research was supported by grants MH-54147 and MH-54623 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Sturm is a senior economist at Rand, 1700 Main Street, Santa Monica, California 90401 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Klap is a researcher at the Health Services Research Center at the University of California, Los Angeles.

|

Table 1. Distribution of claims for behavioral health care from enrollees in 75 carve-out managed care plans in 1996, by provider type

|

Table 2. Percentage of claims filed by patients with selected diagnoses in 75 carve-out managed care plans in 1996, by provider type1

1 Based on 193,688 claims for 28,405 patients

1. Sturm R, Meredith LS, Wells KB: Provider choice and continuity for the treatment of depression. Medical Care 34:723-734, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Wells KB, Sturm R, Sherbourne CD, et al: Caring for Depression. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

3. Sturm R, Wells KB: How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA 273:51-58, 1995Google Scholar

4. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Cuffel B, et al: Outpatient utilization patterns of integrated and split psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Psychiatric Services 49:477-482, 1998Link, Google Scholar

5. Oss ME, Drissel AB, Clary J: Managed Behavioral Health Market Share in the United States, 1997-1998. Gettysburg, Penn, Behavioral Health Industry News, 1997Google Scholar

6. Wells KB, Manning WG Jr, Duan N, et al: Cost-sharing and the use of general medical physicians for outpatient mental health care. Health Services Research 22:1-17, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

7. Frank RG, Kamlett M: Determining provider choice for the treatment of mental disorder: the role of health and mental health status. Health Services Research 24:83-103, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Costs and incentives in a mental health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

9. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17(2):40-51, 1998Google Scholar

10. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 48:1147-1152, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health care coverage under managed care? JAMA 278:1533-1537, 1997Google Scholar

12. Sturm R, McCulloch J: Mental health and substance abuse benefits in carve-out plans and the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. Journal of Health Care Finance 24:82-92, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

13. Schoenbaum M, Zhang W, Sturm R: Costs and utilization of substance abuse care in a privately insured population under managed care. Psychiatric Services 49:1573-1578, 1998Link, Google Scholar