Issues in the Psychiatric Treatment of African Americans

Abstract

African Americans constitute about 12 percent of the United States population. Sixty percent of African Americans live in urban areas, and 25 percent have incomes below the poverty level. Issues in the psychiatric assessment and evaluation of African-American patients include diagnostic bias that has resulted in overdiagnosis of schizophrenia. Use of screening instruments can help standardize assessment, but appropriate screening instruments that have been evaluated and found reliable in this population must be used. Issues in treatment and outcome for African Americans include challenges in establishing rapport in interethnic situations, racial identity as a focus in psychotherapy, and awareness of biological characteristics that affect response to medications. Many African Americans live in high-crime areas where high rates of drug abuse and violence create chronic stresses. Patients with dual diagnoses of chronic mental illness and substance use or abuse need targeted interventions. Strategies for prevention and treatment of the effects of having experienced or witnessed violence have been proposed. Additional research is needed to clarify the true prevalence of specific mental disorders among African Americans and to determine the most effective combinations of treatment strategies for various disorders.

African Americans constitute one group within the black population of the U.S. (1), which also includes an increasing number of African Caribbeans and Africans. The latter groups contribute to an increasing diversity in language, customs, and issues of acculturation within the black American population (2,3). However, African Americans make up the majority of the black population of the U.S. in the 1990s (1,4).

African Americans are the descendants of persons who were brought from West Africa as part of the slave trade or who worked as indentured servants before the development of chattel slavery. Before 1900 most African Americans resided in the Southern part of the U.S., but many moved to Midwestern states and the West during the 1920s and 1930s. Through fighting in several wars, including the War of Independence, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, and through protesting, overcoming legalized segregation, and developing increasing self-awareness and a sense of mastery from the Black Liberation Movement of the 1960s, African Americans have achieved increasing opportunities in education, careers, and housing (1,4).

In this paper we summarize current demographic and epidemiological data about the African-American population and discuss concerns about appropriate psychiatric assessment and evaluation for African Americans, general issues in treatment and outcomes, and particular treatment concerns related to problems of substance abuse and violence that disproportionately affect African-American communities. Finally, we suggest directions for future research to address psychiatric treatment concerns for African Americans.

The African-American population

African Americans constitute 12 percent of the total U.S. population. Fifty-three percent of the African-American population are women. Although African-American men outnumber African-American women at birth, by the time African Americans reach the 15- to 24-year age group, this pattern is reversed. This initial decline in the number of African-American men is due to homicide, suicide, and substance abuse.

This decline continues throughout the life cycle (1) due to accidents and medical problems, discussed below. In the 65- to 74-year age group, there are 67 men for every 100 women. The gender ratio among African Americans age 85 and older is 46 men to 100 women (5). African Americans age 65 and older constitute 11 percent of the total African-American population (1,5).

More than 60 percent of the population reside in urban settings, and 25 percent have incomes below the poverty level. Active medical problems of concern among African Americans include obesity, hypertension, congestive heart failure, glaucoma, and cancer of the prostate, cervix, breast, and colon (6). Mental disorders of concern include schizophrenia, unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, multi-infarct dementia, Alzheimer's disease, trauma-related disorders, and substance abuse (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Psychosocial stressors experienced by African Americans are related to socioeconomic status, residence in high-crime areas, perceived racial discrimination, and perceived limitations on attainments (9,10).

Psychiatric assessment and evaluation

Issues that create particular concern in the assessment and evaluation of psychiatric conditions among African Americans include diagnostic bias and selection of appropriate screening instruments. Clinicians must also be aware of the impact of the patient's psychosocial context on the assessment process. Many African Americans live on marginal incomes in high-crime areas where high rates of drug abuse and unemployment produce chronic stresses.

Diagnostic bias

Since the 1970s studies have reported overdiagnosis of schizophrenia and underdiagnosis of affective disorders among African Americans, compared with the overall prevalence of these disorders in the psychiatric inpatient population (11,12,13,14,15,16,17). However, when diagnoses were based on structured clinical interviews and Research Diagnostic Criteria or diagnostic criteria from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, African-American inpatients were shown to have rates of schizophrenia and depression similar to those of whites admitted to the same inpatient units (18,19,20).

Some investigators have suggested the misdiagnosis of schizophrenia might be related to clinicians' misinterpreting the hallucinations frequently seen with depression among African Americans (14,16). In addition, clinician prejudice has been discussed as a reason for overdiagnosis of schizophrenia among black patients (11,12,13,14,15,16,17). Retrospective studies of the diagnoses of African-American patients in treatment at a Veterans Affairs medical center (17) and at a community mental health center (21) have shown that misdiagnosis has remained a problem in the 1990s.

The prevalence of anxiety disorders among African Americans has not been well studied (22). Survey data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study sites in Baltimore and Durham, North Carolina, suggested a higher lifetime prevalence of simple phobia among black Americans, compared with white community residents (23). Bell and associates (24,25) reported that African Americans have a prevalence of isolated sleep paralysis of approximately 41 percent. African Americans who have frequent episodes of isolated sleep paralysis were found to be more likely to have panic disorder (26), an observation confirmed by Freedman and colleagues (27) and Neal and others (28). These findings suggest that the evaluating clinician should explore with African-American patients the criteria for symptoms of these disorders during the initial evaluation sessions.

Clinicians who evaluate African-American patients should be prepared to question old diagnoses, such as a diagnosis of schizophrenia made 20 years ago. As described by Bell and others (13), alcoholic hallucinosis or alcohol withdrawal states may mimic the hallucinations and agitation of an acute psychotic episode. If previous evaluating clinicians did not explore the substance abuse history of the black patient, the role of alcohol in the genesis of symptoms may have been missed. Alternatively, symptoms of hypomania may have been ignored due to the diagnostic bias of the clinician, resulting in a diagnosis of schizophrenia rather than the correct diagnosis of bipolar disorder (11,12,15,16).

The prevalence of substance abuse and dependence in the population of many cities confounds both the process of evaluation and the process of diagnosis. Withdrawal delirium and paranoid psychosis may be seen among patients who abuse alcohol. Cocaine-induced mood disorder with intense dysphoria and suicidal ideation is a frequent complaint of cocaine-dependent persons evaluated in emergency medical settings. Paranoid psychosis with a clear sensorium may be seen among abusers of crystal methamphetamine. The potential contribution of substances and the varying effects based on the route of use—nasal, inhaled into the lungs, or intravenous—must be considered in the differential diagnosis of the symptoms being evaluated. A routine toxicology screen is an important diagnostic tool, particularly in settings serving populations with a high prevalence of substance abuse and dependence.

Screening instruments

The use of screening instruments to standardize the identification of symptoms and to characterize their intensity can simplify the assessment process. But the instruments that are selected must be chosen with the characteristics of the population being evaluated in mind.

If an African-American elder has less than a sixth-grade education, screening for cognitive impairment may require the use of the Short Portable Mental Status Examination (SPMSE) (29). The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (30) is an effective screening tool for African Americans with at least an eighth-grade reading level. Studies that have reviewed the various screening instruments for cognitive impairment have shown that the MMSE is reliable for use with both rural and urban African-American populations, including elderly persons (31,32). Because years of education may not be congruent with an individual's current reading level (33,34), the clinician may find it helpful to incorporate a short reading-comprehension test—such as a three-sentence paragraph at an eighth-grade reading level—into the initial assessment.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was developed to screen populations for the presence of depressive symptoms (35). The CES-D has been used with clinical populations and has been shown to be more reliable than the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (36) in screening African-American elders for the presence of depressive symptoms (37).

Although the GDS was developed specifically to screen older persons for the presence of depressive symptoms, questions about somatic complaints were not included because it was believed that complaints such as sleep problems, indigestion, headaches, and muscle aches and pains would likely be due to medical illnesses and the multiple medications frequently used by older persons (36). However, African-American elders who are experiencing a depressive episode are likely to report somatic symptoms (38). Because the GDS eliminated these items, it was found to be less reliable in identifying the presence of depressive symptoms among African-American elders (36).

The Hamilton Depression Scale (HDS), which is based on the clinician's impression of symptoms reported by the patient during an interview, is useful for monitoring change from the initial clinical presentation (39). It has been used effectively with African-American populations of all ages.

For the overall assessment of the presence of psychopathology, the Short Psychiatric Evaluation Schedule (SPES) developed by Pfeiffer (40) may be a useful general screening instrument. Symptoms of depression, paranoia, and somatic complaints are included in the 15-item, forced-choice, yes-no format. The SPES can be administered in five minutes and can alert the clinician to a greater severity of symptoms than is spontaneously reported by the patient. It is also useful for identifying changes in the patient's level of symptom severity during treatment.

The use of screening instruments that specify the level of specific symptoms can be particularly helpful in the current clinical environment where clinicians are increasingly required to provide specific target goals for treatment to be accomplished in a given interval. A decline in the CES-D score from 42 to 15 or a change in the HDS from 21 to 8 are both evidence of a decline in the level of depressive symptoms. A change in the MMSE score from 19 to 24 or in the SPMSE score from 9 to 4 provides evidence of a return to normal cognitive function. A change in the SPES score from 14 to 4 indicates the resolution of acute symptoms.

Several instruments are available to assess cognitive function, delirium, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and other phenomena. The clinician should establish that any instrument being considered for use with an African-American patient has been evaluated and found reliable in this population. If the clinician has special concerns about an instrument, such as the potential for education or socioeconomic status to affect its results, the choice of another instrument without the potential biases would be preferable.

Treatment and outcome

Establishing rapport with African-American psychiatric patients may pose particular challenges for white clinicians. The difficulty in establishing rapport in interethnic and intercultural situations (41) may be confounded by patients' reactions to antipsychiatry literature that has been targeted to the African-American community (42). Clinicians must be prepared to explore antipsychiatry feelings with African-American patients to counteract the negative effects of antipsychiatry propaganda they may have heard.

African-American therapists and therapists of color must be sensitive to issues of countertransference and premature interpretation. Even if the patient and therapist have had similar experiences with society and education and have similar interests, the therapist still needs to learn about and understand the specific choices that patient has made and the techniques that the patient has used to cope with psychosocial stresses. If the patient and therapist have very dissimilar backgrounds and life experiences, the therapist will need to be aware that some verbal and nonverbal behavior, such as an active, probing interview or the nonverbal listening stance, may be perceived as rejecting by the patient.

Empirical literature and research reports on the psychotherapeutic treatment needs of African Americans have historically been lacking (43). More recently, Carter (44) has given some attention to the issue of race and racial identity in psychotherapy. He suggested that such issues influence engagement with the African-American patient regardless of the race of the therapist. Building on the work of Pierce (45), Bell (46) proposed that a major treatment issue for African Americans in the 1990s was confusion about racism. Bell underscored the observation that was made initially by Pinderhughes (47) that African Americans struggle with issues of self-identify and self-determination. Aponte (48) emphasized the need to address the philosophical and spiritual needs of poor nonwhite patients, as well as their daily life needs to be truly helpful to these patients.

Recently, an increasing number of studies have addressed biologic and pharmacologic issues in the treatment of African Americans. Lin and associates (49) questioned whether there may be higher levels of beta2-adrenoceptor activity among blacks, resulting in reduced response to the beta blockers used to treat various disorders. Other studies have suggested that African Americans may respond better and more rapidly to tricyclic antidepressants than whites (50). A recent report suggested that African Americans were more likely than whites to be nonresponders to fluoxetine (51). Lin and his colleagues (52) found that African Americans have significantly greater effects than other racial groups from a specific benzodiazepine as evidenced by changes in psychomotor performance.

Strickland and his colleagues (53) noted that the literature consistently shows that African Americans have less efficient lithium-sodium countertransport ability at the cell membrane and a relatively higher ratio of red blood cell counts to plasma lithium levels, compared with whites. These findings suggest that African Americans may need less lithium to achieve effective control of manic symptoms. The use of lithium in treating African-American patients with bipolar disorder who also have sickle cell anemia remains unstudied.

Sue and colleagues (54) observed that the paucity of treatment outcome studies involving nonwhite patients makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of psychiatric treatments for these populations. In light of the continuing problem of misdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders in African-American patients, it is probably safe to assume that patients who are given an incorrect diagnosis are not likely to have an optimal treatment outcome. Studies to establish specific data about this issue are needed.

One recent study addressed the two-year outcome for chronic mentally ill African-American patients who were involved in an aggressive, seven-day-a-week psychosocial rehabilitation program (55). These patients showed an improved level of function, a significant decrease in hospitalizations, and improved use of leisure time. A subsample of patients with dual diagnoses also showed improvement after 24 months of treatment.

Substance abuse and violence

Substance abuse and dependence is endemic in many urban communities. The epidemic of cocaine dependence continues, frequently associated with alcohol abuse. Heroin dependence has declined from its peak in the 1960s, but use of heroin has begun to increase in the 1990s. In some states the use of crystal methamphetamine is of increasing concern. The agents used to dilute street drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and marijuana may be toxic themselves, producing additional medical problems—for example, dermatitis and hepatotoxicity—in association with the problems of drug dependence.

Although patients with dual diagnosis—chronic mental illness and substance abuse or dependence—constitute only one segment of the population with mental illness in the African-American community, dual diagnosis remains a significant issue. Too frequently the African-American patient with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder may be dependent on cocaine or alcohol and may use marijuana intermittently. Thus the possibility that substance use or abuse is exacerbating the psychotic or affective illness must be considered for a patient who fails to stabilize with repeated, sequential adjustments in treatment. Patients with a dual diagnosis—who frequently become homeless as their social network becomes exhausted—require targeted and specific interventions (56,57,58).

Interventions to break the cycle involving acute decompensation due to substance abuse, stabilization, repeat drug use, and acute decompensation due to an episode of mental illness begin with the correct identification of the cause of the decompensation. Interviews with family members and friends to explore the context and course of the patient's acute mood or personality changes and random screening of the patient using urine drug tests may help clarify the etiology of recurrent acute exacerbations of illness and explain why the patient has failed to stabilize. Confrontation about substance dependence and education about the negative effects of drugs on mental illness should be part of the revised treatment plan.

If inpatient detoxification is available, patients who acknowledge that they have a problem and state that they wish to change should be offered this intervention. For highly motivated persons, ambulatory detoxification may be helpful. Inpatient detoxification combined with supervised, residential housing in the community away from the prior environment may interrupt the cycle of decompensation, stabilize the patient, and return the patient to a point of minimal symptoms. Once the patient is stable, participation in a psychosocial rehabilitation program may be feasible.

Assertive community treatment (56,57) has been used successfully as an intervention for homeless dually diagnosed persons (59). Although the prognosis for this population is guarded, stabilization of the patient helps to clarify the baseline of the psychotic or affective illness that is present and improves the patient's likelihood of successful engagement in a meaningful treatment program.

The clinician must also remember that a patient's failure to improve with treatment may reflect a misdiagnosis. A patient with bipolar disorder misdiagnosed as having paranoid schizophrenia will continue to have cyclical episodes of illness until a mood stabilizer is included in the treatment regimen. The African-American patient with schizophrenia and a simple phobia will continue to be symptomatic until the treatment plan addresses both disorders (20).

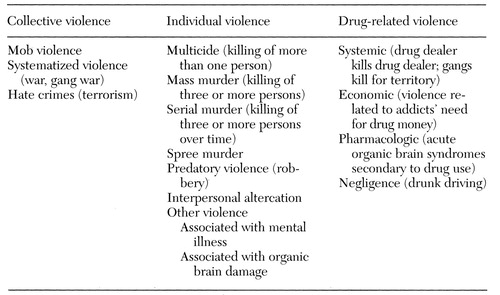

Violence—a multifaceted phenomenon with multiple etiologies (60)—is receiving more attention in the African-American community. Table 1 shows a conceptional model developed by Bell (60) that clarifies the context, target, and outcome of violence. The epidemic of violence toward others or toward self and the frequent episodes of collective violence have affected all age cohorts in many African-American communities (61). African-American children who are witnesses to violence have been shown to experience a variety of psychiatric symptoms (8). Adolescents, particularly African-American young men, may find a peer group in joining a gang, but they also increase their risk of experiencing individual or group violence.

Analysis of sex crimes in major cities such as Chicago has revealed that a high proportion of African-American women have been victims of a sexual assault (62). In the absence of treatment, sexually assaulted women may not report the attack and may later develop symptoms of various anxiety disorders. Elderly African Americans may fear being mugged and avoid leaving their homes alone to shop or do other errands. Specific programs of intervention against violence, which include strategies for prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation, have been proposed (60).

Research directions

Clarification of the psychiatric diagnoses of African-American patients in treatment is crucial. A patient with bipolar disorder or alcohol hallucinosis who was misdiagnosed and has been treated for more than 20 years for paranoid schizophrenia is at risk for developing tardive dyskinesia as a result of long-term use of antipsychotic medication. Clarifying the diagnosis, adjusting the treatment plan, and educating the patient about the mental illness and its course with and without treatment are important treatment and rehabilitation goals, and continued research to clarify the extent of misdiagnosis among African Americans with mental illness is needed.

Specific populations should be studied to establish which treatment sites—state hospitals, community mental health centers, university hospitals, jails, or psychosocial rehabilitation programs—are most effective for the diagnosis and treatment of African-American patients. The cost savings resulting from decreased hospitalizations for misdiagnosed "refractory patients" who have failed to respond to conventional treatment could be substantial.

Educational programs about the specific illness, its course, and the effects of medication in African-American populations should include both the patient and the patient's family members or caregivers. Continuing medical education courses should be developed to share data from these programs with mental health professionals.

Studies of the outcome of treatment for African-American patients are sorely needed. For patients who have received accurate diagnoses, which combinations of psychotherapy, psychopharmacology, and behavioral therapies are most effective for which disorders among African-American patients? Are different treatment strategies needed for African Americans who live in urban versus rural areas? What interventions are most effective for children, adolescents, adults, and elders? Rigorously designed studies to establish the outcomes of treatment strategies for specific psychiatric disorders in various age groups are needed.

The study of the prevalence of specific mental disorders among African-American populations has been limited. Although the National Black Survey provided some data about psychosocial stressors experienced by a national sample of African Americans age 18 and older, it did not assess the presence of specific psychiatric disorders (63). Data are needed to address the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms and disorders among urban and rural African Americans age six and older. This information would help in planning for specific services and interventions and preventive strategies.

The level of violence within American society continues to escalate. Elders, adults, adolescents, and children are affected. Interventions to help children describe and express their feelings after witnessing the death of classmates or family members have begun to be implemented (64). Strategies to help adults living in communities with both individual and drug-related violence have not been organized on a national level. The establishment of pilot programs to identify the most effective strategies for children, adolescents, adults, and elders would help both the African-American community and the larger community.

Successful and effective models developed to aid children dealing with predatory violence (robbery), interpersonal altercation violence, and drug-related violence should be available for any school or similar group experiencing such stressful events. Research is urgently needed to develop prevention efforts at all levels—primary prevention, including training in conflict management and anger management techniques to "immunize" against individual and collective violence; secondary prevention, including treatment in the immediate aftermath of violence; and tertiary prevention, including rehabilitation for the longer term.

Finally, the issue of suicide among African-American youth needs to be systematically studied. Analysis of suicide rates among African-American male adolescents in the 15- to 19-year age range showed that rates have steadily increased from 2.3 per 100,000 in 1960 (65) to 16.6 per 100,000 in 1994 (Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Injury Prevention, unpublished data, 1995). It has been proposed that the rising rate of African-American male suicide is due to the presence of major mental disorder along with the sociological circumstances such as alienation and a sense of being trapped that African-American youth experience (66). Such hypotheses must be tested in empirical research.

Conclusions

Clinicians who treat African-American patients should be aware that schizophrenia has been overdiagnosed and affective disorders underdiagnosed in this population. Issues in the psychiatric assessment and evaluation of African-American patients include the use of appropriate screening instruments that have been evaluated and found reliable for this population and recognition of the effects of a patient's psychosocial context, which may include living on marginal incomes in areas with high rates of crime and unemployment. Issues in treatment of African Americans include challenges in establishing rapport in interethnic situations and the need to explore antipsychiatry feelings. Racial identity and confusion about racism may be major issues in psychotherapy. An increasing literature has been addressing biological characteristics that affect African Americans' response to medications.

Many African Americans live in high-crime areas where high rates of drug abuse and violence create chronic stresses. Targeted interventions for patients with dual diagnoses of chronic mental illness and substance use or abuse are needed, as are interventions to prevent violence and to treat the effects of having experienced or witnessed violence.

Additional research is needed to clarify the extent of misdiagnosis and the true prevalence of specific mental disorders among African Americans. Treatment outcome studies to determine the most effective combinations of treatment strategies for various disorders are also needed. The effectiveness of intervention strategies to prevent violence and treat its effects should be examined. Additional research is also needed to clarify the causes of the rising rate of suicide among young African-American men.

Dr. Baker is professor of psychiatry at the John A. Burns School of Medicine of the University of Hawaii at Manoa and Hawaii State Hospital, 45-170 Keaahala Road, Kaneohe, Hawaii 96744-3597. Dr. Bell is chief executive officer of the Community Mental Health Council, Inc., in Chicago and professor in the departments of psychiatry and public health at the University of Illinois in Chicago. This paper is the first in a quarterly series on the psychiatric needs of nonwhite populations in the United States.

|

Table 1. Conceptual model of violence1

1 Violence is a multifaceted phenomenon with multiple etiologies that can be directed toward self (suicidal behavior) or others (homicidal behavior) and that can have lethal or nonlethal outcomes. Adapted from Bell (60)

1. Griffith EEH, Baker FM: Psychiatric care of African Americans, in Culture, Ethnicity, and Mental Illness. Edited by Gaw AC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

2. Spurlock J: Black Americans, in Cross-Cultural Psychiatry. Edited by Gaw A. Littleton, Mass, Wright-PSG, 1982Google Scholar

3. Allen EA: West Indians, in Clinical Guidelines in Cross-Cultural Mental Health. Edited by Comas-Dias L, Griffith EEH. New York, Wiley, 1988Google Scholar

4. Baker FM: Psychiatric treatment of older African Americans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:32-37, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Baker FM: Ethnic elders: minority issues in geriatric psychiatry, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 7th ed. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1999Google Scholar

6. Baker FM, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Jones BE: Acute care of the African American elder. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 6:66-71, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Wilkinson CB, Spurlock J: The mental health of black Americans: psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, in Ethic Psychiatry. Edited by Wilkerson CB. New York, Plenum, 1986Google Scholar

8. Jenkins EJ, Bell CC: Exposure and response to community violence among children and adolescents, in Children in a Violent Society. Edited by Osofsky J. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

9. Neighbors HW: Mental health, in Life in Black America. Edited by Jackson JS. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1991Google Scholar

10. Braithwaite RL, Taylor SE: African-American health: an introduction, in Health Issues in the Black Community. Edited by Braithwaite RL, Taylor SE. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1992Google Scholar

11. Bell C, Mehta H: The misdiagnosis of black patients with manic depressive illness. Journal of the National Medical Association 72:141-145, 1980Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bell CC, Mehta H: Misdiagnosis of black patients with manic depressive illness: second in a series. Journal of the National Medical Association 73:101-107, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

13. Bell CC, Thompson JP, Lewis D, et al: Misdiagnosis of alcohol-related organic brain syndromes: implications for treatment, in Treatment of Black Alcoholics. Edited by Brisbane FL, Womble M. Binghamton, NY, Haworth, 1985Google Scholar

14. Adebimpe VR: Overview: white norms and psychiatric diagnosis of black patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:279- 285, 1981Link, Google Scholar

15. Jones BE, Gray BA, Parson EB: Manic-depressive illness among poor urban blacks. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:654- 657, 1981Link, Google Scholar

16. Adebimpe VR: Hallucinations and delusions in black psychiatric patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 73:517-520, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

17. Coleman D, Baker FM: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia among older black veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:527-528, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Liss JL, Welner A, Robins E, et al: Psychiatric symptoms in white and black inpatients: I. record study Comprehensive Psychiatry 14:475-481, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Welner A, Liss JL, Robins E: Psychiatric symptoms in white and black inpatients: II. follow-up study. Comprehensive Psychiatry 14:483-488, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Simon RJ, Fleiss JL, Gurland BJ, et al: Depression and schizophrenia in black and white mental patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 28:509-512, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Baker FM: Misdiagnosis among older psychiatric patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 87:872-876, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

22. Neal AM, Turner S: Anxiety disorders research with African-Americans: current status. Psychological Bulletin 109:400-410, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Weissman MM, et al: Lifetime prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders in three sites. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:949-958, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bell CC, Shakoor B, Thompson B, et al: The prevalence of isolated sleep paralysis in blacks. Journal of the National Medical Association 76:501-508, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

25. Bell CC, Hildreth C, Jenkins EJ, et al: The relationship between isolated sleep paralysis, panic disorder, and hypertension. Journal of the National Medical Association 80:289-294, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

26. Bell CC, Dixie-Bell DD, Thompson B: Further studies on the prevalence of isolated sleep paralysis in black subjects. Journal of the National Medical Association 78:649-659, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

27. Freedman S, Paradis CM, Hatch M: Characteristics of African-American and white patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:798-803, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Neal AM, Rich LN, Smucker WD: The presence of panic disorder among African American hypertensives: a pilot study. Journal of Black Psychology 20(1):29-35, 1994Google Scholar

29. Pfeiffer E: A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficits in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 23:433- 441, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: "Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:189-198, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Baker FM: Screening tests for cognitive impairment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:339-340, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

32. Fillenbaum G, Heyman A, Williams K, et al: Sensitivity and specificity of standardized screenings for cognitive impairment and dementia among elderly black and white community residents. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 43:651-660, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Launer LJ, Dinkgreve MAHM, Jonker C, et al: Are age and education independent correlates of the Mini-Mental State Exam performance of community-dwelling elderly? Journal of Gerontology 48:271-277, 1993Google Scholar

34. Baker FM, Johnson JT, Vellie SA, et al: Congruence between education and reading levels of older persons. Psychiatric Services 47:194-196, 1996Link, Google Scholar

35. Ratloff LS: The CES-D: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 3:385-401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al: Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research 17:37-49, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Baker FM, Velli SA, Friedman J, et al: Screening tests for depression in older black vs white patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 3:43-51, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Baker FM, Lightfoot OB: Psychiatric care of ethnic elders, in Culture, Ethnicity, and Mental Illness. Edited by Gaw AC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

39. Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 32:50-57, 1959Google Scholar

40. Pfeiffer E: A short psychiatric evaluation schedule, in Bayer Symposium VII: Brain Function in Old Age. Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 1979Google Scholar

41. Aponte JF, Young-Rivers R, Wohl J (eds): Psychological Interventions and Cultural Diversity. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 1995Google Scholar

42. Bell CC: Pimping the African-American community. Psychiatric Services 47:1025, 1996Link, Google Scholar

43. Jones BE, Gray BA: Black and white psychiatrists: therapy with blacks. Journal of the National Medical Association 77:19-25, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

44. Carter RT: The Influence of Race and Racial Identity in Psychotherapy. New York, Wiley, 1995Google Scholar

45. Pierce CM: Stress in the workplace, in Black Families in Crisis. Edited by Conner-Edwards AF, Spurlock J. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1988Google Scholar

46. Bell CC: Treatment issues for African-American men. Psychiatric Annals 26:33- 36, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

47. Pinderhughes CA: Racism and psychotherapy, in Racism and Mental Health. Edited by Willie CV, Kramer BM, Brown BS. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993Google Scholar

48. Aponte HJ: Bread and Spirit: Therapy With the New Poor. New York, Norton, 1994Google Scholar

49. Lin K, Poland RE, Silver B: Overview: the interface between psychobiology and ethnicity, in Psychopharmacology and Psychobiology of Ethnicity. Edited by Lin K, Poland RE, Nakasaki G. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

50. Silver B, Poland RE, Lin K: Ethnicity and the pharmacology of tricyclic antidepressants, ibidGoogle Scholar

51. Wagner GJ, Maguen S, Rabkin JG: Ethnic differences in response to fluoxetine in a controlled trial with depressed HIV-positive patients. Psychiatric Services 49:239- 240, 1998Link, Google Scholar

52. Lin K, Poland RE, Fleishaker JC, et al: Ethnicity and differential response to benzodiazepines, in Psychopharmacology and Psychobiology of Ethnicity. Edited by Lin K, Poland RE, Nakasaki G. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

53. Strickland TL, Lawson W, Lin K, et al: Interethnic variation in response to lithium therapy among African-Americans and Asian-American populations, ibidGoogle Scholar

54. Sue S, Chun C, Gee K: Ethnic minority intervention and treatment research, in Psychological Interventions and Cultural Diversity. Edited by Aponte JF, Young-Rivers R, Wohl J. Boston, Allyn & Bacon, 1995Google Scholar

55. Baker FM, Stokes-Thompson J, Davis OA, et al: Psychosocial rehabilitation of the black chronically mentally ill: two-year outcome. Psychiatric Services, in pressGoogle Scholar

56. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trials. Psychiatric Services 46:669-675, 1995Link, Google Scholar

57. Teague GB, Drake RE, Ackerson TH: Evaluating use of continuous treatment teams for persons with mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 46:689-695, 1995Link, Google Scholar

58. Johnson S: Dual diagnosis of severe mental illness and substance misuse: a case for specialist services. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:205-208, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1038-1043, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Bell CC: Community violence: causes, prevention, and intervention. Journal of the National Medical Association 89:657-662, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

61. Griffith EEH, Bell CC: Recent trends in suicide and homicide among blacks. JAMA 262:2265-2269, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Pardo N: Black rape victims lack refuge. Chicago Reporter 26(6):3-5, 1997Google Scholar

63. Neighbors HW, Jackson JS (eds): Mental Health in Black America. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1996Google Scholar

64. Osofsky J (ed): Children in a Violent Society. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

65. Hollinger PC, Offer D, Barter J, et al: Suicide and Homicide Among Adolescents. New York, Guilford, 1994Google Scholar

66. Bell CC, Clark D: Adolescent suicide. Pediatric Clinics of North America 45(2):365-380, 1998Google Scholar