Psychopharmacology: Novel Antipsychotic Medications in the Treatment of Children and Adolescents

Antipsychotic medications are commonly prescribed to treat a variety of psychiatric disorders and symptoms among children and adolescents, although the manufacturers of these drugs have generally tested and marketed them for the treatment of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia among adults. Studies have suggested that conventional antipsychotics are likewise effective for the treatment of schizophrenia in children and adolescents (1,2). However, as psychosis is rare in children and adolescents, these drugs are more often used to treat nonpsychotic phenomena such as aggression (3,4), hyperactivity (5), Tourette's disorder (6), and pervasive developmental disorder (7,8,9,10,11). Moreover, Zito and associates (12) found that antipsychotics were the most commonly prescribed class of drugs for children and adolescents treated as psychiatric inpatients and that the drugs were prescribed for disorders other than schizophrenia.

In 1989 the novel ("atypical") antipsychotic clozapine was marketed for the treatment of schizophrenia. Clozapine is unlike the conventional ("typical") antipsychotics in several ways, including its low incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms and its ability to blockade not only the D2 receptor but also the HT2 receptor. Clozapine's potential advantages over conventional antipsychotics include its usefulness for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. In addition, its use is rarely associated with the development of dyskinesias. Unfortunately, use of clozapine is associated with a higher than usual risk of agranulocytosis, which can be lethal.

Newer antipsychotics that are similar to clozapine in some ways have been marketed recently. They include risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine, all of which, like clozapine, are referred to as novel or atypical antipsychotics. Because they have a lower incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms, including an implied lower propensity for causing dyskinesia, they are prescribed to children and adolescents. However, industry-sponsored trials for these agents, as for most psychotropics, have generally excluded children and adolescents.

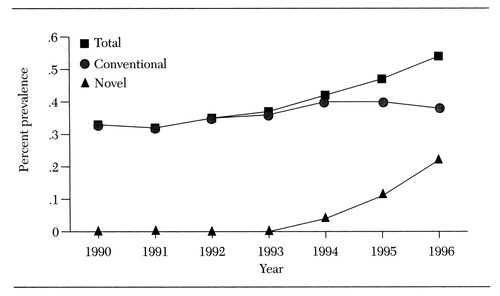

This column gives an overview of the evidence for the use of these agents in treating children and adolescents. Such an overview is timely because the administration of antipsychotics to children and adolescents is on the rise. For example, as Figure 1 shows, among children and adolescents from a large Midwestern Medicaid population, usage increased by as much as a 63 percent between 1990 and 1996, due primarily to prescription of the novel antipsychotics (Zito JM, Safer D, Gardner J, unpublished data, 1998). Clozapine and risperidone were available during the period shown in the figure, but olanzapine and quetiapine were not yet available.

Clozapine

Clozapine, a dibenzodiazepine, was approved for use in the U.S. in 1989, the first novel antipsychotic to be approved for use in this country. Clozapine was found to be effective in addressing treatment-resistant schizophrenia among adults (13). However, patients who are prescribed clozapine must have weekly blood monitoring because use of the drug carries the risk of life-threatening agranulocytosis.

Studies of the use of clozapine with children and adolescents have been reported. Kumra and associates (14) investigated the safety and efficacy of clozapine for treating childhood-onset schizophrenia by comparing clozapine to haloperidol in a randomized double-blind study. The subjects ranged in age from six to 18 years and had a history of poor response to antipsychotics. Clozapine at doses ranging from 25 to 525 mg per day (mean±SD dose=176±149 mg) was found to be more effective than haloperidol at doses ranging from 7 to 27 mg per day (mean±SD dose=16±8 mg). Clozapine was found to be particularly effective in treating negative symptoms.

The doses of haloperidol used in this study were higher than those used in other controlled trials of its effects in treating childhood-onset schizophrenia (2) and in treating children with autism (10), and the higher doses may have increased the ratings of negative symptoms among subjects who received haloperidol. A third of the subjects in the clozapine group experienced side effects, which included neutropenia and seizures. A number of other side effects, including excessive weight gain, have been noted with use of clozapine (15).

A controlled clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of clozapine, olanzapine, and placebo for the treatment of childhood-onset schizophrenia is under way (16). Results of open trials of clozapine for adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia (17,18) and case reports of its use for this group of patients (19,20,21) have been published.

In summary, although clozapine shows promise in the treatment of childhood-onset schizophrenia, it is likely to be a treatment of last resort because of the risk of serious side effects such as neutropenia and seizures, and the need for frequent blood monitoring.

Risperidone

Risperidone, a benzisoxole derivative, was introduced to the market in 1993. To date no controlled trials of the use of risperidone for treatment of children and adolescents have been reported, although the literature includes reports on open trials and case studies.

Armenteros and associates (22) reported on the short-term efficacy and safety of risperidone in an open trial involving ten adolescents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Risperidone was administered twice a day in doses that ranged from 4 to 10 mg per day (mean=6.6 mg per day). The investigators found that risperidone was efficacious but that its use was associated with weight gain, sedation, and extrapyramidal symptoms including acute dystonic reactions. Currently, Armenteros is conducting a double-blind and placebo-controlled study of risperidone for adolescents with schizophrenia. Several case reports and a retrospective chart review describe the use of risperidone in treatment of schizophrenia or psychosis (23,24,25,26,27,28).

Risperidone has been used to treat pervasive developmental disorder in small open trials (29,30,31,32), and a few case reports have described this use (33,34). Controlled trials of this drug for pervasive developmental disorder, as for schizophrenia, have been conducted with only adult subjects (35).

The only reports of the use of risperidone in treatment of Tourette's disorder have been descriptions of open trials (36) and a retrospective chart review (37), although the findings suggest that the drug is efficacious. The most common side effect reported was weight gain. It is important to note that dyskinesias related to risperidone have been reported among children and adolescents (31, 38), and cases of hepatotoxicity have also been reported (39).

In summary, risperidone has not been studied systematically and critically for use among children and adolescents, although such studies are under way. However, the reports to date are encouraging and suggest that risperidone may be useful for treating some children and adolescents.

Olanzapine

Olanzapine is an novel thienobenzodiazepine introduced to the market in 1996. No controlled trials of olanzapine in treatment of children and adolescents have been reported, although, as mentioned above, a controlled trial comparing clozapine, olanzapine, and placebo for childhood-onset schizophrenia is under way. Kumra and colleagues (16) reported on an open trial in which olanzapine was effective for symptoms of childhood-onset schizophrenia. In this study eight subjects aged ten to 17 years were treated with olanzapine in doses ranging from 12.5 to 20 mg per day (mean±SD dose=17.5±2.3 mg). The main side effects were increased appetite, constipation, nausea or vomiting, headache, somnolence, insomnia, difficulty concentrating, sustained tachycardia, transient elevation of liver transaminase levels, and increased agitation. During the trial period, abnormal movements and extrapyramidal symptoms were minimal.

The remainder of the literature on olanzapine consists of case reports of its use in treatment of Tourette's disorder (40), pervasive developmental disorder (30), and mental retardation (41). Controlled studies of this novel antipsychotic in the treatment of children and adolescents are needed.

Quetiapine

Quetiapine fumarate is a novel dibenzothiazepine (42) first marketed in 1997. There are no published controlled trials examining its use in the treatment of children and adolescents. McConville and associates (43) reported results from an open-label study of the pharmacokinetics and tolerability of this agent among ten adolescents with psychotic disorders who were between ages 12 and 17. Subjects received the drug twice a day for 21 days, and doses were increased in a stepwise fashion to 100 mg per day and then to 400 mg per day. The results suggested that quetiapine may be tolerable in short-term usage and may hold promise as a treatment for this population.

In some animal studies, quetiapine was found to be associated with the development of cataracts. Although no clear evidence suggests that lens changes will occur in humans, the possibility cannot be ruled out. The manufacturer recommends that patients' lenses should be examined for signs of cataracts before beginning the drug and at six-month intervals while on the drug (44). Again, controlled studies of this novel antipsychotic involving children and adolescents are lacking.

Discussion

The novel antipsychotics show promise in the treatment of some psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents. However, the promise may be related more to the novel agents' similarities to the conventional antipsychotics, for which we have more data and experience, than to the limited data on the novel agents themselves. Although controlled trials of the novel antipsychotics are being conducted, few such studies have been completed.

The lack of controlled trials is not surprising—with the exception of stimulants, few psychoactive agents have been tested in controlled clinical drug trials involving children and adolescents (45). The lack of controlled trials is of particular concern when one considers the high rate of psychotherapeutic drug treatment among children and adolescents (46,12), especially in light of the sociological issues and controversy surrounding the use of these agents for the young (47). Furthermore, psychotropic medications are administered clinically to children and adolescents, often for prolonged periods of time. From the data available, it is difficult to assess the effects that the novel antipsychotics will have on learning and cognition, areas of importance in developing children and adolescents.

Because these drugs are likely to be used for the long term, it is important to investigate the risk of dyskinesias among children and adolescents. It should not be forgotten that the conventional antipsychotics were used for several years before drug-related dyskinesias were described. In a prospective study of haloperidol in treatment of children with autism, dyskinesias were found to occur. This finding led to the recommendation that the drug be withdrawn periodically to assess the need for its continued use and to observe for withdrawal dyskinesias, which may be an early form of tardive dyskinesia (10). This recommendation should also apply to the novel antipsychotics, particularly as data on their long-term use among children and adolescents are lacking.

Perhaps of greater concern is the potential effect these drugs may have on weight gain. Weight gain is a risk factor for many health conditions, including cardiovascular diseases and diabetes (48), and can affect patients' self-esteem and their willingness to comply with treatment.

Unlike the conventional antipsychotics, the novel agents, apart from risperidone, generally do not cause increases in prolactin. By increasing prolactin, conventional antipsychotics may cause amenorrhea and thereby decrease the fertility of female patients. Thus, when female patients are switched from conventional to novel agents, the possibility of pregnancy may be increased.

Conclusions

Very few systematic studies of the novel antipsychotics in the treatment of children and adolescents have been done. Many psychopharmacologists say that the conventional antipsychotics play a reduced role in modern treatment of adults. Although conventional antipsychotics may also eventually play less of a role in the treatment of some diagnoses among children and adolescents, we need more data before such a conclusion can be drawn. It is understandable that those who thoughtfully treat children and adolescents often prescribe drugs that have not been labeled or studied for use in this population. However, more efforts to systematically study the effects of the novel antipsychotics among children and adolescents are crucial, particularly as evidence suggests an increase in clinical usage.

Acknowledgment

This work was partly supported by grant MH-00979 from the U.S. Public Health Service to Dr. Malone.

Dr. Malone is associate professor and Dr. Sheikh is clinical instructor in the department of psychiatry at MCP Hahnemann University School of Medicine in Philadelphia. Dr. Malone is also director of child and adolescent psychiatry research in the department of psychiatry at Eastern Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute in Philadelphia. Dr. Zito is associate professor in the department of pharmacology practice and science at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. Address correspondence to Dr. Malone at Eastern Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute, 3200 Henry Avenue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19129 (e-mail, [email protected]). George M. Simpson, M.D., is editor of this column.

Figure 1. Prevalence of the use of conventional and novel antipsychotics among youths nder age 20 in large Midwestern Medical population, per 100 youths, 1990-1996

1. Pool D, Bloom W, Mielke D, et al: A controlled evaluation of loxitane in seventy-five adolescent schizophrenic patients. Current Therapeutic Research 19:99-104, 1976Medline, Google Scholar

2. Spencer E, Kafantaris V, Padrone-Gayol MV, et al: Haloperidol in schizophrenic children: early findings from a study in progress. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 28:183-186, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

3. Campbell M, Small AM, Green WH, et al: Behavioral efficacy of haloperidol and lithium carbonate: a comparison in hospitalized aggressive children with conduct disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:650-656, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Greenhill LL, Barmack JE, Spalten D, et al: Molindone hydrochloride in the treatment of aggressive hospitalized children. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 17:125-127, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

5. Gittelman-Klein R, Klein DF, Katz S, et al: Comparative effects of methylphenidate and thioridazine in hyperkinetic children: clinical results. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:1217-1231, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Shapiro E, Shapiro AK, Fulop G, et al: Controlled study of haloperidol, pimozide, and placebo for the treatment of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:722-730, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Anderson LT, Campbell M, Grega DM, et al: Haloperidol in the treatment of infantile autism: effects on learning and behavioral symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:1195-1202, 1984Link, Google Scholar

8. Anderson LT, Campbell M, Adams P, et al: The effects of haloperidol on discrimination learning and behavioral symptoms in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 19:227-239, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Campbell M, Anderson LT, Meier M, et al: A comparison of haloperidol and behavior therapy and their interaction in autistic children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 17:640-655, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Campbell M, Armenteros JL, Malone RP, et al: Neuroleptic-related dyskinesias in autistic children: a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:835-843, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cohen IL, Campbell M, Posner D, et al: Behavioral effects of haloperidol in young autistic children: an objective analysis using a within-subjects reversal design. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 19:665-677, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Zito JM, Craig TJ, Wanderling J: Pharmacoepidemiology of 330 child/adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Pharmacoepidemiology 3(1):47-62, 1994Google Scholar

13. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:789-796, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kumra S, Frazier JA, Jacobsen LK, et al: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: a double-blind clozapine-haloperidol comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:1090-1097, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Gordon CT, Frazier JA, McKenna K, et al: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: an NIMH study in progress. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:697-712, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kumra S, Jacobsen LK, Lenane M, et al: Childhood-onset schizophrenia: an open-label study of olanzapine in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:377-385, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Frazier JA, Gordon CT, McKenna K, et al: An open trial of clozapine in 11 adolescents with childhood-onset schizophrenia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:658-663, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Remschmidt H, Schultz E, Martin M: An open trial of clozapine in thirty-six adolescents with schizophrenia. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 4:31-41, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Birmaher B, Baker R, Kapur S, et al: Clozapine for the treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:160-164, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Kowatch RA, Suppes T, Gilfillan SK, et al: Clozapine treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a clinical case series. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 5:241-253, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Mozes T, Toren P, Chernauzan N, et al: Clozapine treatment in very early onset schizophrenia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:65-70, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Armenteros JL, Whitaker AH, Welikson M: Risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open pilot study. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:694-700, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Cozza SJ, Edison DL: Risperidone in adolescents (ltr). Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 33:1211, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Cosgrove F: Recent advances in paediatric psychopharmacology (ltr). Human Psychopharmacology 9:381-382, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Dryden-Edwards RC, Reiss AL: Differential response of psychotic and obsessive symptoms to risperidone in an adolescent. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 6:139-145, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Lykes WC, Cueva JE: Risperidone in children with schizophrenia (ltr). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:405-406, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Quintana H, Keshavan M: Case study: risperidone in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:1292-1296, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Grcevich SJ, Findling RL, Rowane WA, et al: Risperidone in the treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia: a retrospective study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 6:251-257, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Findling RL, Maxwell K, Wiznitzer M: An open clinical trial of risperidone monotherapy in young children with autistic disorder. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 33:155-159, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

30. Horrigan JP, Barnhill LJ, Courvoisie HE: Olanzapine in PDD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:1166-1167, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Malone RP, Rowan AB, Blaney BL, et al: Open risperidone in pervasive developmental disorder (abs). Psychopharmacology Bulletin 33:553, 1997Google Scholar

32. Perry R, Pataki C, Munoz-Silva DM, et al: Risperidone in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorder: a pilot trial and follow-up. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 7:167-179, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Demb HB: Risperidone in young children with pervasive developmental disorders and other developmental disabilities (ltr). Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 6:79-80, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Hardan A, Johnson K, Johnson C, et al: Case study: risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with developmental disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1551-1556, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. McDougle CJ, Holmes JP, Carlson DC, et al: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone in adults with autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:633-641, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Lombroso PJ, Scahill L, King RA, et al: Risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with chronic tic disorders: a preliminary report. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:1147-1152, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Mandoki MW: Risperidone in the treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette's disorder (abs). Biological Psychiatry 37:618, 1995Google Scholar

38. Rowan AB, Malone RP: Tics with risperidone withdrawal (ltr). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:162-163, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Kumra S, Herion D, Jacobsen LK, et al: Case study: risperidone-induced hepatotoxicity in pediatric patients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:701-705, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Bhadrinath BR: Olanzapine in Tourette syndrome (ltr). British Journal of Psychiatry 172:366, 1998Google Scholar

41. Rubin M: Use of atypical antipsychotics in children with mental retardation, autism, and other developmental disabilities. Psychiatric Annals 27:219-221, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Small JG, Hirsch SR, Arvanitis LA, et al: Quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia: a high- and low-dose double-blind comparison with placebo. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:549-557, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. McConville B, Arvanitis LA, Wong J, et al: Pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and clinical effectiveness of quetiapine fumerate in adolescents with selected psychotic disorders. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, Ont, May 30-June 4, 1998Google Scholar

44. Seroquel package insert. Wilmington, Del, Zeneca Pharmaceuticals, 1997Google Scholar

45. Jensen PS, Vitiello B, Leonard H, et al: Design and methodology issues for clinical treatment trials in children and adolescents. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 30:3-8, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

46. Kaplan SL, Simms RM, Busner J: Prescribing practices of outpatient child psychiatrists. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:35-44, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Zito JM, Riddle MA: Psychiatric pharmacoepidemiology for children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 4:77-95, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

48. Pi-Sunyer FX: Medical hazards of obesity. Annals of Internal Medicine 119(7, pt 2):655-660, 1993Google Scholar