Best Practices: Use of Risperidone and Olanzapine in Outpatient Clinics at Six Veterans Affairs Hospitals

The atypical antipsychotic medications risperidone and olanzapine are enjoying widespread use in psychiatry. They are considered atypical primarily because of their ability to alter negative symptoms and their relative paucity of side effects. Although the two drugs differ in their pharmacology and side effect profiles (1,2,3), they are grouped together and referred to by the imprecise nomenclature of "atypical." This lack of precision is a danger only if decisions about the drugs are based on the category to which they have been assigned and not on their individual properties.

The study reported here describes patterns of prescribing for risperidone and olanzapine in outpatient clinics at six hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system. Although the data do not identify differences between the two drugs in efficacy, effectiveness, cost, or safety, they do suggest how clinicians have chosen to use the drugs, and that information will ultimately contribute to our knowledge about the best practices for these medications.

Methods

Data on medications dispensed to outpatients at each of six VA hospital pharmacies were collected for each quarter of 1997. The information involved more than 12,000 prescriptions for risperidone and olanzapine. The data were collated by hospital and by drug and included doses, numbers of prescriptions, costs per day, and patient visits per year. In addition, data on average dose by diagnostic group, number of prescriptions by diagnostic group, average dose by age group, and types of drugs prescribed by age group were available for one of the six hospitals.

Results

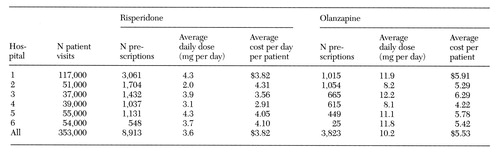

Among the six hospitals, 8,913 prescriptions for risperidone and 3,823 prescriptions for olanzapine were written. Data on average daily doses and average daily costs for these medications and the number of prescriptions written for these medications at each hospital are presented in Table 1. All diagnostic groups are represented in these data.

The total average dose per day was 3.6 mg for risperidone and 10.2 mg for olanzapine. The range of average daily doses of risperidone was only 2.3 mg, with four of the six hospitals within .6 mg of each other. The average dose per day for both medications did not vary more than 4 percent throughout the year. The range of daily doses for olanzapine was similarly restricted. The highest mg-per-day dose was 4.1 mg more than the lowest, and four of the six hospitals had daily doses within 1.1 mg of each other. The average daily cost of the drugs per patient varied among the six hospitals, ranging from $2.91 to $4.31 for risperidone and from $4.22 to $6.29 for olanzapine.

Table 1 also shows the number of outpatient psychiatry visits per year for each hospital. The number of visits did not appear to correlate with any of the other variables included in the description of prescribing patterns.

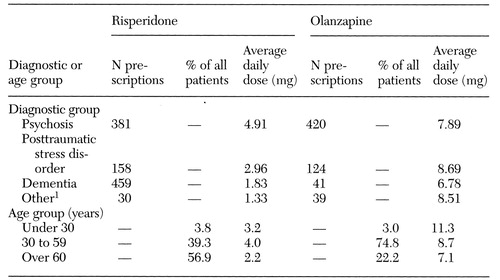

Table 2 shows data for hospital 4, for which more detailed information on doses and number of prescriptions by diagnostic and age groups was available. In this academically affiliated hospital, the average dose of olanzapine was 20 percent lower and the average dose of risperidone was 14 percent lower than the overall average for the rest of the hospitals. A total of 420 prescriptions for olanzapine were written for treatment of psychosis and 41 for treatment of dementia. As for prescriptions of risperidone, 381 were written for treatment of psychosis and 459 for treatment of dementia.

In this hospital, the average daily dose for risperidone was 4.9 mg for patients with psychotic disorders, 3 mg for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, and 1.8 mg for patients with dementia. Olanzapine was used in average daily doses of 7.9 mg for patients with psychotic disorders, 8.7 mg for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, and 6.8 mg for patients with dementia.

The patients who received olanzapine tended to be younger than those who received risperidone. About 75 percent of the patients who received olanzapine were between age 30 and 59, compared with 39 percent of the patients who received risperidone. The age group with the highest use of risperidone was the 70- to 79-year age group. Olanzapine was most frequently prescribed for patients in the 40- to 49-year age group.

As one might expect, the average dose per day generally decreased with advancing age. Among patients prescribed risperidone, those age 30 to 59 had the highest average daily dose (4 mg) and those over age 60 had the lowest (2.2 mg). The highest average daily dose of olanzapine—11.3 mg—was prescribed to patients under age 30; patients over age 60 received the lowest dose, 7.1 mg.

In all the hospitals, for risperidone the average daily dose by quarter for the year 1997 was 3.5 mg in the first quarter, 3.7 mg in the second, 3.6 mg in the third, and 3.6 mg in the fourth. For olanzapine, the average daily doses for the four quarters were 10.5 mg, 10.9 mg, 10 mg, and 10 mg. The quarterly average daily doses of risperidone did not vary by more than .25 mg over the year, and those of olanzapine did not vary by more than 1 mg over the year.

Discussion and conclusions

In the six VA hospitals in this study, clinicians prescribed average daily doses of 10.2 mg of olanzapine and 3.6 mg of risperidone. The variances in dosing between the hospitals—which were less than 4 percent—were not as great as might be expected. Of course, without data for the different locations on the effectiveness of these medications as reflected in hospital admission rates and patient satisfaction, controlling for illness severity, this observation is difficult to interpret.

The average daily costs of the two drugs varied considerably more than their average daily doses. Based on the experience of the hospital for which detailed data were available, this difference could be explained by differences in the diagnostic and age groups of the patients more likely to be prescribed each of the medications. Risperidone appeared to be prescribed more frequently for older patients with dementia, for whom smaller doses are required, while olanzapine was prescribed more frequently for younger patients with psychotic disorders, for whom doses and thus costs are higher.

However, cost analyses such as those reported here, which are based on drug acquisition costs, are seriously limited because they say nothing about the pharmacoeconomic properties of a given drug. The data reported here show that olanzapine has higher acquisition costs. However, this finding does not mean that olanzapine actually "costs" more than risperidone. To reach that conclusion, one would need a pharmacoeconomic analysis in which all direct and indirect costs involved in treatment were measured (4).

In the hospital for which detailed data were available, the use of atypical antipsychotics for treatment of dementia and posttraumatic stress disorder was, at the time of the study, outside of the recommended uses described in the drug manufacturers' product labeling. This observation probably reflects the fact that practice is ahead of science in this area and illustrates the importance of the best-practices exercise in helping systems of care recognize potential uses of medications. Of course, efficacy and effectiveness studies are needed to help conclude that these drugs work better in these populations than the older typical agents. But the finding should caution systems of care to view the prescribing guidelines in manufacturers' labeling as just that: guidelines.

Given the study's limitations, the results suggest that the two most popular atypical antipsychotics are being used differently. The term "atypical" may not be adequate to describe this growing group of drugs, and any attempt to coalesce these very different drugs into a single category will not treat their differences appropriately. It is important to merge other clinical data with dispensing data from pharmacies to help improve our ability to understand best practices in clinical settings.

Dr. Voris is associate professor at the College of Pharmacy of the University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina 29208. Dr. Glazer, the editor of this column, is associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

|

Table 1. Numbers of prescriptions of risperidone and olanzapine, average daily doses and costs, and number of patient visits in 1997 in outpatient clinics at six Veterans Health Administration hospitals

|

Table 2. Average daily doses and numbers of prescriptions for risperidone and olanzapine at hospital 4, by diagnostic and age group

1No "diagnosis" was the primary constituent of the "other" group.

1. Physician's Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics, 1998, pp 1309-1313, 1512-1516Google Scholar

2. Stahl SM: Essential Psychopharmacology. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp 263-288.Google Scholar

3. Richelson E: Preclinical pharmacology of neuroleptics: focus on new generation compounds. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 11):4-11, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

4. Glazer WM, Johnstone BM: Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of antipsychotic therapy for schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58(suppl 10):50-54, 1997Medline, Google Scholar