A Collaborative Community-Based Treatment Program for Offenders With Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The paper describes initial results of collaboration between a mental health treatment program at a community mental health center in Baltimore and a probation officer of the U.S. federal prison system to serve the mental health needs of offenders on federal probation, parole, supervised release, or conditional release in the community. METHODS: A forensic psychiatrist in the treatment program and a licensed social worker in the probation office facilitate the close working relationship between the agencies. Treatment services provided or brokered by the community mental health center staff include psychiatric and medical treatment, intensive case management, addictions treatment, urine toxicology screening, psychosocial or residential rehabilitation services, intensive outpatient care, partial hospitalization, and inpatient treatment. RESULTS: Among the 16 offenders referred for treatment during the first 24 months of the collaborative program, 14 were male and 14 were African American. Three of the 16 violated the terms of their release due to noncompliance with stipulated mental health treatment; only one of the three had been successfully engaged in treatment. One patient died, two completed their terms of supervision, and ten remained in treatment at the time of the report. CONCLUSIONS: The major strength of this collaboration is the cooperation of the treatment and monitoring agencies with the overall goal of maintaining the offender in the community. Further research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of the clinical model in reducing recidivism and retaining clients.

In 1857 the American Journal of Insanity, which later became the American Journal of Psychiatry, published an article by Edward Jarvis, M.D., of Dorchester, Massachusetts (1), that suggests the plight of criminal offenders with mental illness and their need for care are not recent phenomena. Dr. Jarvis wrote, "The insane criminal has nowhere any home: no age or nation has provided a place for him. He is everywhere unwelcome and objectionable. The prisons thrust him out; the hospitals are unwilling to receive him; the law will not let him stay at his house, and the public will not permit him to go abroad. And yet humanity and justice, the sense of common danger, and a tender regard for a deeply degraded brother-man, all agree that something should be done for him—that some plan must be devised different from, and better than any that has yet been tried, by which he may be properly cared for, by which his malady may be healed, and his criminal propensity overcome."

Today society continues to face the challenge of providing proper care for offenders with mental disorders within the growing population of persons under the jurisdiction of the correctional system in the United States. This paper briefly reviews recent research on the prevalence of mental illness among criminal offenders and the effects of clinical interventions with this population. It describes a small model program for offenders with mental illness that involves collaboration between clinical staff of a community mental health center and a probation officer from the U.S. correctional system.

Background

Persons with mental illness in the correctional system

Between 1980 and 1995, the number of people incarcerated in jails and prisons more than tripled, increasing from 501,886 to 1,577,845. The incarceration rate also nearly tripled during that time, from about 150 per 100,000 persons in 1980 to more than 400 per 100,000 in 1995 (2).

Mirroring the rise in the number of inmates is a tripling in the number of citizens under the community supervision of parole and probation officers. Between 1980 and 1996, this number increased from 1,338,535 to 3,885,072 (2,3). Thus the total correctional population increased threefold between 1980 and 1995, when more than 5.3 million people were serving an institutional or community correctional sentence in the U.S. (2).

The rate of mental illness is two to three times higher among those incarcerated in jails and in prisons than in the general population (4,5,6,7), and a disproportionate number of persons with mental illness are arrested, compared with the general population (4). In addition, the mental health needs of this population are grossly underaddressed while they are incarcerated. Among others, Torrey and colleagues (8) have described the "abuse of jails as mental hospitals" and have called for active diversion programs that will identify offenders with mental illness and their needs for mental health interventions early in the criminal justice process. Such diversion programs often rely on very active and proactive case management to create a community-based treatment plan that will meet the medical and psychiatric needs of the patient while ensuring compliance with public safety mandates (9).

Much less is known of the fate of persons with mental illness who are convicted of serious crimes and are sent to prison. A high rate of mental illness among convicted felons has been reported, with rates ranging from 6 to 15 percent (6). A survey of New York state prison inmates revealed that 8 percent had a severe psychiatric or functional disability, and an additional 16 percent suffered from significant mental disabilities requiring at least periodic care (10).

Even less is known about the treatment received by this population once they leave the prison environment and are on parole (11). Similarly, little is known about treatment received by convicted criminals who are placed on probation and do not serve prison time.

Some research has focused on the criminal recidivism of the mentally ill offender. A recent study found that the offenders with mental illness had a rate of recidivism equivalent to that of a matched control group of non-mentally-ill offenders (12). However, the same group of researchers have reported that the introduction of pre- and postrelease interagency coordination significantly reduced the recidivism risk in a pilot study (13). Another study recently reported that the introduction of case management services led to a significant decrease in the recidivism rate of offenders with mental illness (14). Yet another demonstrated that judicially monitored treatment resulted in good outcomes during a one-year follow-up phase (15). Taken together, this work indicates that offenders with mental illness are highly likely to have ongoing contact with the criminal justice and correctional systems and that clinical interventions may affect their recidivism rate.

A clash of two systems

One of the biggest barriers to care for offenders is the mutual distrust that exists between mental health providers and the community correctional system. Frequently, the mental health system is seen by corrections as "soft" on crime, as uninterested in public safety, and as having the tendency to make excuses for criminals with mental illness. In addition, mental health care providers are often thought not to understand the special forensic needs of this population.

Conversely, mental health professionals often view the correctional system as lacking any understanding of the mental health needs of its charges. In particular, community mental health providers frequently assume that community corrections personnel often seek revocation of the client's probation or parole. Mental health providers may also come to the treatment process with the belief that "forced treatment doesn't work" (16,17). Simple fear is often the covert reason for providers' refusal to accept referrals of clients who have committed crimes. Responding in part to their fear, providers may not accept a referral until they receive documentation about prior treatment, which is not always available to the probation officer. Providers also may be reluctant to treat offenders with mental illness because of the potential for court appearances.

These barriers may be overcome in exceptional cases by proactive work from either the clinical or the correctional side (18). For instance, Sluder and associates (19) reviewed a philosophy of probation in which the probation officers are "resource brokers" whose responsibilities include not only ensuring public safety but also helping their clients meet their social needs, including mental health needs, where appropriate. Their review also includes a summary of the literature documenting the importance of treatment in lowering recidivism rates.

However, rehabilitation and the role of treatment continue to be controversial in corrections. Such interventions are frequently labeled "intermediate sanctions" and are viewed as part of a higher-intensity model of probation based on the premise that providing treatment in whatever area it is required will reduce recidivism. Some research supports this hypothesis (20). Conversely, one of the drawbacks of intensive supervision is that increased monitoring appears to increase the likelihood that problematic behavior will be noticed and the offender's probation revoked (19,21). It is important for researchers to distinguish the increase in the recidivism rate related to higher-intensity supervision from the increase related to the higher risk inherent in the group of offenders assigned to intermediate sanctions.

To effectively serve this population, a collaborative and proactive approach involving mental health care providers and corrections personnel is clearly needed (22,23). Ideally, cross-trained workers from each discipline would become partners in this effort and would share common goals. Work from several countries over a long period of time has supported this thesis (23,24,25,26,27).

For example, in the United Kingdom, national policy supports efforts to ensure that offenders with mental illness receive necessary treatment in the community rather than while incarcerated (23). A number of systemic interventions have been undertaken to ensure that this policy receives attention from both the legal sector and the mental health and social services sector (28,29). The importance of interagency cooperation and coordination is emphasized, and funding has been allocated when necessary to ensure this cooperation (29).

This paper describes a small model program involving the collaboration of a community mental health center and the United States Probation Office to address the complex needs of this population. The program was developed to ensure high-quality coordination of care, with ongoing feedback between clinical and probation personnel. Characteristics of the clientele and preliminary descriptive outcome data are presented here.

Methods

In response to a wide disparity in ease of access to neighborhood clinics, the second author, a probation officer with the United States Probation Office in Baltimore City, determined that an alternative approach was needed if his clients were to receive adequate mental health and addiction services. In April 1996, he contracted with a specific provider of care for services to his caseload of offenders on federal parole, probation, and supervised release who were mentally ill.

The clinical model in use in this program—a fairly typical community mental health model—is described in detail elsewhere (30). Briefly, each patient, or offender, is assigned to a psychiatrist, the first author, and one of the program's two master's-level therapists is assigned to work with the probation officer. Care within the community mental health center is coordinated by the clinicians and may include medical treatment, intensive case management, addictions treatment, urine toxicology screening, and psychosocial or residential rehabilitation services. Services are provided elsewhere for patients who may need a period of more intensive care, such as intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization, or inpatient treatment. These services are brokered by the community mental health center's clinical team.

All patients who are referred to the community mental health center are informed at the beginning of the evaluation process and throughout treatment of the close connection and frequent contact between the clinicians and the probation officer. The probation officer is routinely kept informed of patients' clinical progress. If a patient misses an appointment or the treatment team notices other forms of treatment noncompliance, the probation officer may act in an outreach function for the clinical program. Decisions about changes in patients' housing, major alterations of the treatment plan, or discontinuation of services always involve the probation officer's input.

Results

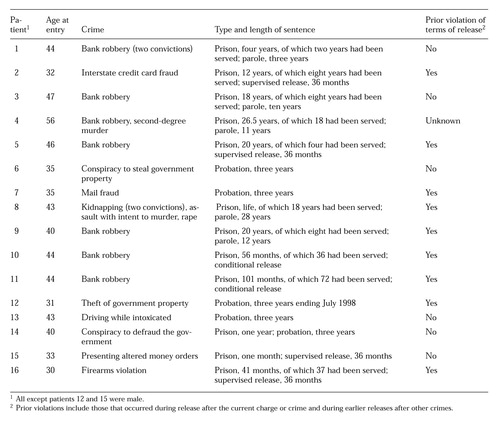

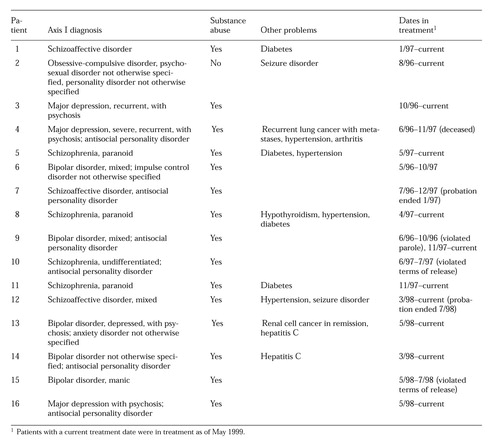

We present descriptive data from the first group of offenders enrolled in this clinical model, with emphasis on length of tenure in the treatment program. As of May 1998 a total of 16 patients had been referred for treatment by the probation officer. Table 1 and Table 2 show the legal and clinical characteristics of the patients. Fourteen were male, and 14 were African American, reflecting the offender population of Baltimore City. They ranged in age from 30 to 56 years. All had been accepted into treatment, although one patient kept only two appointments and another kept just one. Both of these patients violated the terms of their community supervision by noncompliance with stipulations for mental health treatment. One other patient violated the terms of his parole because of noncompliance with treatment; however, the noncompliance occurred after he was hospitalized in an attempt to keep him in active treatment. After he was released and referred back to the treatment team, he did well in treatment.

Thus of the 16 referrals, three patients received criminal sanctions due to noncompliance with treatment. Only one of these patients had been successfully engaged in treatment before violating the terms of his release. As noted in Table 1, nine of the 16 patients in this cohort had a history of parole or probation violations.

The terms of supervision for two patients had expired or were terminated as of May 1999. One completed his term eight months after beginning treatment under the contracted arrangement. He remained a voluntary patient with the treatment team for 11 months after his supervision was terminated and then failed to keep appointments, and his case was closed. The probation of another patient was terminated within four months after she started treatment; she remained in treatment in May 1999, ten months after her probation ended.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper is the first we have found that reports data from a collaborative clinical-probation treatment model for offenders with mental illness. Because the program was designed as a clinical intervention, without prospective research questions, the conclusions that can be drawn from the clinical data are limited. Nonetheless, the data are intriguing and suggest the need for further study.

In the cohort of patients described, the rate of violation of probation, parole, or supervision was 19 percent. This same group of offenders had a violation rate of 56 percent before their current release. Several of the patients had violated the terms of their release numerous times in the past, but the data presented here suggest that the program's intervention may have had an impact on the level of compliance with conditions of release.

We suggest that this result can be attributed in part to the close working relationship between the clinical team and the probation officer. The ongoing regular contact has allowed the clinicians who work with these clients to develop an understanding of the community supervision system and of its responsibilities for public safety. In turn, the social work background of the probation officer has helped him understand his clients' mental health needs and the operation of the mental health treatment system. In situations where many probation officers might rapidly seek revocation of supervision, the existence of this contract and the cooperation between the contracting agencies allows all treatment options, including voluntary and involuntary hospitalization, to be exhausted before sanctions are deemed necessary.

An important facet of this program is its capacity to address co-occurring mental and addictive disorders in an integrated fashion. Most of the patients referred to the mental health center have already been involved in the center's substance abuse program. Often their mental health needs were initially met by consulting psychiatrists working in the addictions treatment program. However, the needs of many patients for therapy or case management outstripped the capacity of the addiction treatment staff, and many patients were referred to the mental health program. In all of these cases, the patient continued to be involved in the substance abuse program, which includes urine toxicology screens and drug counseling. The two programs are located in the same building, which facilitates their collaboration to successfully treat dual diagnoses and to respond to the public safety requirements of the probation officer.

The contractual arrangement has enhanced the probation officer's access to a wide range of mental health services for his clients. Before the development of the contract, sources of mental health care were chosen based on the catchment area in which the client lived. The probation officer repeatedly faced the need to educate new clinicians about the corrections system, and development of a firm working alliance was unlikely because only one or two clients were being treated in any particular clinic.

The contract has made the mental health center's clinicians accountable to the probation officer both clinically and fiscally. In return, the probation officer can assure the clinicians of his ongoing support. In some cases, the probation officer has served as an outreach contact when patients begin to decompensate or to miss appointments. This added outreach has allowed the mental health center clinicians to provide fairly intensive treatment, without having to refer these offenders to more costly treatment programs. The collaboration has hinged on the consensus that information sharing would be used in the interest of patients' treatment needs and that legal sanctions for patients' violation of the terms of release would be a last resort.

A major problem for widespread application of the treatment model is the lack of coordination between the prison system and the community correctional system. For example, because the federal prisons constitute a nationwide system, an offender with mental illness may be housed in a prison located hundreds of miles from his or her eventual community placement. Prison staff are unlikely to be aware of the resources in the city where the inmate is to be released and must rely on the local probation officer's knowledge of community resources for essential prerelease case management. However, not all probation officers are aware of community resources that would be appropriate for offenders with mental illness.

As noted, the program described here was not designed with a priori research questions in mind. Thus a major drawback of this descriptive study is the absence of a control group, making it impossible to form conclusions about the effectiveness of the clinical model in retaining its clients or in reducing recidivism. Using the cohort as its own control might lead to the conclusion that the treatment model is effective, at least in broad terms of violations of parole or probation. In our opinion, this conclusion is not valid, given the large number of uncontrolled variables, including length of time in the community before violation of release terms and reason for the violation.

Although we have the impression that the model has resulted in reduced burden of illness to the offenders enrolled in the program and to a lower rate of criminal activity, these findings may be the result of the cohort's older age range, from 30 to 56 years. Older age has been associated with remission of antisocial symptoms (31).

Despite these drawbacks of the study, this collaborative model appears to be applicable to many settings in which the mental health and community correctional systems interact. Research should be conducted to test the cost-effectiveness and clinical and criminal justice outcomes of this approach. Although our model involves the federal correctional system, it could also be used in other correctional systems. The working relationship of clinical and community correctional personnel meets the mental health needs of the patients while ensuring that the safety interests of the courts and the public are protected, in a cost-effective, efficacious, and humane manner.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Fred Osher, M.D.

Dr. Roskes is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore and with the Walter P. Carter Clinics of the University of Maryland Medical System, Box 291, 22 South Greene Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 (e-mail, [email protected]). Mr. Feldman is with the U.S. Probation Office in Baltimore. This paper is part of a special section on mentally ill offenders.

|

Table 1. Legal characteristics of 16 offenders with mental illness who participated in a model community-based treatment program between May 1996 and May 1999

|

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of 16 offenders with mental illness who participated in a model community-based treatment program between May 1996 and May 1999

1. Jarvis E: Criminal insane: insane transgressors and insane convicts. American Journal of Insanity 13:195-231, 1857Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Corrections Facts at a Glance. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, May 27, 1997. Available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/glance/corr2.txtGoogle Scholar

3. Nation's probation and parole population reached almost 3.9 million last year (press release). Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Aug 14, 1997. Available at http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/pub/bjs/press/papp96.prGoogle Scholar

4. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483-492, 1998Link, Google Scholar

5. Metzner JL: An introduction to correctional psychiatry, part I. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:375-381, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

6. Veysey BM: Annual report, in Challenges for the Future: Topics in Community Corrections. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice and the National Institute of Corrections, 1994Google Scholar

7. Fryers T, Brugha T, Grounds A, et al: Severe mental illness in prisoners. British Medical Journal 317:1025-1026, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Torrey EF, Stieber J, Ezekiel J, et al: Criminalizing the seriously mentally ill: the abuse of jails as mental hospitals. Innovations and Research 2(1):11-14, 1993Google Scholar

9. Steadman HJ, McCarty DW, Morrissey JP: The Mentally Ill in Jail: Planning for Essential Services. New York, Guilford, 1989Google Scholar

10. Steadman HJ, Fabisiak S, Dvoskin J, et al: A survey of mental disability among state prison inmates. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:1086-1090, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Solomon P, Draine J: Issues in serving the forensic client. Social Work 40:25-33, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

12. Harris V, Koepsell TD: Rearrest among mentally ill offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 26:393-402, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

13. Harris V, Trupin E, Wood P: Mentally ill offenders and community transitions. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, New Orleans, Oct 24, 1998Google Scholar

14. Ventura LA, Cassel CA, Jacoby JE, et al: Case management and recidivism of mentally ill persons released from jail. Psychiatric Services 49:1330-1337, 1998Link, Google Scholar

15. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Reston-Parham C: Court intervention to address the mental health needs of mentally ill offenders. Psychiatric Services 47:275-281, 1996Link, Google Scholar

16. Commitment to outpatient treatment, in Forced Into Treatment: The Role of Coercion in Clinical Practice. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry report 137. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

17. Involuntary Commitment to Outpatient Treatment. APA task force report 26. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

18. Peters RH, Hills HA: Intervention Strategies for Offenders With Co-Occurring Disorders: What Works? LaCrosse, Wisc, International Community Corrections Association, Dec 1997Google Scholar

19. Sluder RD, Sapp AD, Langston DC: Guiding philosophies for probation in the 21st century. Federal Probation 58(2):3-10, 1994Google Scholar

20. Byrne J, Brewster M: Choosing the future of American corrections: punishment or reform? Federal Probation 57(4):3-9, 1993Google Scholar

21. Solomon P, Draine J, Myerson A: Jail recidivism and receipt of community mental health services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:793-797, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Dvoskin JA, Steadman HJ: Using intensive case management to reduce violence by mentally ill persons in the community. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:679-684, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Vaughan PJ, Badger D: Working With the Mentally Disordered Offender in the Community. London, Chapman & Hall, 1995Google Scholar

24. De Reuck AVS, Porter R: The Mentally Abnormal Offender. Boston, Little, Brown, 1968Google Scholar

25. Stafford KP, Karpawich JJ: Conditional release: court-ordered outpatient treatment for insanity acquittees. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 75:61-72, 1997Google Scholar

26. Forced Into Treatment: The Role of Coercion in Clinical Practice. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry report 137. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

27. Prins H: The care of the psychiatric prisoner: discharge into the community and its implications. Medicine, Science, and the Law 23(2):79-86, 1983Google Scholar

28. Provision for Mentally Disordered Offenders. Home Office circular 66/90. London, Home Office, Sept 3, 1990Google Scholar

29. Mentally Disordered Offenders: Inter-Agency Working. Home Office circular 12/95. London, Home Office, May 9, 1995Google Scholar

30. Roskes E, Feldman R, Arrington S, et al: A model program for the treatment of mentally ill offenders in the community. Community Mental Health Journal 35:461-472, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Meloy JR: Antisocial personality disorder, in Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Gabbard GO. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar