The Effects of Animal-Assisted Therapy on Anxiety Ratings of Hospitalized Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Animal-assisted therapy involves interaction between patients and a trained animal, along with its human owner or handler, with the aim of facilitating patients' progress toward therapeutic goals. This study examined whether a session of animal-assisted therapy reduced the anxiety levels of hospitalized psychiatric patients and whether any differences in reductions in anxiety were associated with patients' diagnoses. METHODS: Study subjects were 230 patients referred for therapeutic recreation sessions. A pre- and posttreatment crossover study design was used to compare the effects of a single animal-assisted therapy session with those of a single regularly scheduled therapeutic recreation session. Before and after participating in the two types of sessions, subjects completed the state scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, a self-report measure of anxiety currently felt. A mixed-models repeated-measures analysis was used to test differences in scores from before and after the two types of sessions. RESULTS: Statistically significant reductions in anxiety scores were found after the animal-assisted therapy session for patients with psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and other disorders, and after the therapeutic recreation session for patients with mood disorders. No statistically significant differences in reduction of anxiety were found between the two types of sessions. CONCLUSIONS: Animal-assisted therapy was associated with reduced state anxiety levels for hospitalized patients with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses, while a routine therapeutic recreation session was associated with reduced levels only for patients with mood disorders.

Within the last decade, studies supporting the health benefits of companion animals have emerged (1,2,3,4). Cardiovascular effects are often the focus, due partly to findings from a 1980 study that reported longer survival rates following myocardial infarction for pet owners compared with people with no pets (5). More recent evidence of cardiovascular benefit was documented in an Australian study involving 5,741 participants (6). The authors found that pet owners had significantly lower blood pressure and triglyceride levels compared with non-pet-owners, and the differences could not be explained by differences in cigarette smoking, diet, body mass index, or socioeconomic profile.

Stress and anxiety are considered contributory factors to cardiovascular disease. Investigators have hypothesized that companion animals may serve to lower levels of stress and anxiety (4,7,8). Several authors have reported lower blood pressure readings among adults and children when a previously unknown companion animal is present during various stressful activities (5,9,10,11,12,13,14).

Animals have been associated with positive effects on patients in a variety of health care settings (15). When animals were first introduced to these settings, they were generally brought for visits that were incidental to the treatment program. Currently, animals are purposely included in treatment through various interventions broadly known as animal-assisted therapy.

Animal-assisted therapy involves the use of trained animals in facilitating patients' progress toward therapeutic goals (16). Interventions vary widely, from long-term arrangements in which patients adopt pets to short-term interactions between patients and a trained animal in structured activities.

Although animals have typically been well received on psychiatric services, much of the data attesting to their benefits has been anecdotal (17,18,19). Several decades ago, Searles (20) and Levinson (21) addressed the therapeutic benefit of a companion dog for patients with schizophrenia, contending that the caring, human-canine relationship helped ground the patient in reality. Chronic mentally ill residents in supportive care homes who were visited by puppies had decreased depression after the visits, compared with a matched control group (22).

More recently, Arnold (23) described the use of therapy dogs with patients with dissociative disorders. Benefits included the dog's calming influence, ability to alert the therapist early to clients' distress, and facilitation of communication and interaction. Others have proposed that an animal can serve as a clinical bridge in psychotherapy, providing an entree to more sensitive issues (16,24,25).

On an inpatient psychiatric unit, animal-assisted therapy was found to attract the greatest number of patients among those who selected groups to attend voluntarily and was found to be the most effective in attracting isolated patients (26). Other researchers found that a group meeting for psychiatric inpatients held in a room where caged finches were located had higher attendance and higher levels of patient participation, and was associated with more improvement in scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, compared with a matched group held in a room without birds (27). Anecdotally, psychiatric patients who are withdrawn and nonresponsive have been described as responding positively to a therapy dog with smiles, hugs, and talking (16). For elderly patients with dementia, lower heart rates and noise levels were associated with the presence of a therapy dog (28), and patients with Alzheimer's disease significantly increased socialization behaviors when a therapy dog was nearby (29).

Based on the evidence in the literature associating companion animals with anxiety reduction and with positive responses from clinical populations, this study investigated the effect of an animal-assisted therapy group session on the anxiety levels of psychiatric inpatients. Also of research interest was whether any anxiolytic effect found varied by diagnostic group.

Methods

A pre- and posttreatment crossover design was used for this study. Changes in anxiety ratings were compared for the same patients under two conditions: a single animal-assisted therapy group session and a single therapeutic recreation group session that served as a comparison condition. The setting for this study was the inpatient psychiatry service of an urban academic medical center. The service treats adult patients with a full range of acute psychiatric disorders. The average length of stay is seven to eight days.

The animal-assisted therapy session consisted of approximately 30 minutes of group interaction with a therapy dog and the dog's owner. During the semistructured session, which was held once a week, the owner talked generally about the dog and encouraged discussion about patients' pets as the dog moved freely about the room interacting with patients or carrying out basic obedience commands.

The comparison condition was a therapeutic recreation group session held on the unit on the day following the animal-assisted therapy session. Therapeutic recreation sessions were held daily on the unit. They varied in content, including education about how to spend leisure time, presentations to increase awareness of leisure resources in the community, and music and art activities. Coordination of both the animal-assisted therapy sessions and the therapeutic recreation sessions was shared by three recreational therapists.

The study used the state scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory to measure patients' levels of anxiety before and after the animal-assisted therapy session and the therapeutic recreation session (30). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory is a brief, easy-to-administer self-report measure that is widely used in research and clinical practice.

The state scale, which measures the level of anxiety felt at the present time, has been found to be sensitive to changes in transitory anxiety experienced by patients in mental health treatment. The inventory consists of 20 items related to feelings of apprehension, nervousness, tension, and worry. For each item, subjects circle one of four numbers corresponding to ratings of not at all, somewhat, moderately so, or very much so. Instruments are scored by calculating the total of the weighted item responses. Scores can range from 20 to 80, with greater scores reflecting higher levels of anxiety.

The internal consistency for the state scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory is high; median alpha coefficient is .93 (30). The construct validity is supported by studies showing that state scale scores are higher under stressful conditions.

Procedures

A total of 313 adult psychiatric patients consecutively referred for therapeutic recreation over an eight-month period in 1996 were eligible for the study. Patients are referred for therapeutic recreation as soon as they are stable enough to participate in group activities, generally within 24 to 72 hours of admission.

When patients were initially referred for therapeutic recreation, they were asked to sign a consent form to participate in a group session involving a therapy dog. Patients were not eligible to participate if they had any known canine allergies, were fearful of dogs, or did not sign a consent form. Study subjects attended both an animal-assisted therapy group session and a therapeutic recreation group session. The two types of sessions were held once a week on consecutive days at the same time on each day.

The three recreational therapists providing services to the inpatient psychiatry unit volunteered to assist with the study. Because the therapists were not blind to the treatment condition, steps were taken to minimize bias by training the therapists in standard data collection procedures. At the beginning and end of each animal-assisted therapy group session and the comparison therapeutic recreation group session the following day, the recreational therapist administered the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. The therapists read the instrument verbatim to any patient who had difficulties reading. For the animal-assisted therapy group, the pretreatment instrument was completed before the dog entered the room.

Two female owners of therapy dogs volunteered to provide the animal-assisted therapy sessions. The first volunteer provided the therapy for the initial four months of the study; then she became ill and could not continue. The second volunteer agreed to continue the study following the same format used by the first volunteer. Her participation required reversing the days that the animal-assisted therapy session and the therapeutic recreation session were offered.

The dogs and owners met hospital policy for participating in animal-assisted therapy, including documentation of the dog's current vaccinations, controllability, and temperament. The volunteers were advised of the animal-assisted therapy group session and given direction on how to lead the therapy group.

Analysis

Instruments were scored twice for accuracy by one of the authors using the scoring keys for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. A mixed-models repeated-measures analysis was used to compare pre- and posttreatment differences in anxiety scores between and within the animal-assisted therapy condition and the therapeutic recreation condition by diagnostic category.

Results

Because this study was conducted in a clinical setting, pre- and posttreatment measures on all subjects under both conditions were difficult to obtain. Six patients refused to participate because of canine allergies or fear of dogs. Of the 313 patients who were eligible for the study, 73 percent (N=230) participated in at least one animal-assisted therapy group session or one recreation group session and completed a pre- and a posttreatment measure for the session. Fifty patients completed a pre- and a posttreatment measure for both types of sessions. Failure to complete all four measures was primarily due to time conflicts with medical treatments and patient discharges.

Patient characteristics

The mean±SD age of the 313 patients referred for therapeutic recreation was 37±12 years, and their mean length of stay was 10.98±8.88 days. A total of 174 patients were women, and 139 were men. The majority were black (169 subjects, or 54 percent) and single (195 subjects, or 63 percent). They had completed an average of 11.3±2.6 years of education.

For analysis, patients were categorized by primary discharge diagnosis. The diagnoses were collapsed into four categories: mood disorders, including all depressive, bipolar, and other mood disorders, for 154 patients (49.2 percent); psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and other psychotic disorders, for 80 patients (25.6 percent); substance use disorders, for 52 patients (16.6 percent); and all other disorders, including anxiety, cognitive, personality, and somatization disorders, for 27 patients (8.6 percent).

Comparison of therapy groups

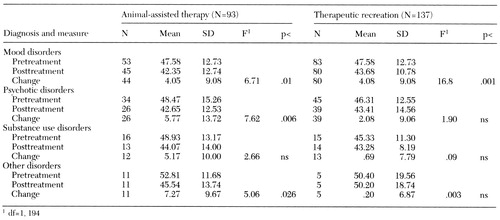

Table 1 shows the mean scores of the 230 study participants on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory before and after attending an animal-assisted therapy group session and a therapeutic recreation group session as well as the mean change scores. Change scores were calculated using data from patients with measures at both pre- and posttreatment time points. The F test and p values show the significance of the change across time. No statistically significant differences in anxiety change scores were found between animal-assisted therapy and therapeutic recreation. Although no significant between-group differences were found, within-group differences were statistically significant for both animal-assisted therapy and therapeutic recreation (F=6.71, df= 1, 194, p=.01, and F=16.81, df=1, 194, p<.001, respectively).

Among patients who participated in therapeutic recreation, only patients with mood disorders had a significant mean decrease in anxiety. Among patients who participated in animal-assisted therapy, patients with mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and other disorders had a significant mean decrease in anxiety. This finding suggests that animal-assisted therapy reduces anxiety for a wider range of patients than the comparison condition of therapeutic recreation.

Discussion and conclusions

Spielberger (30) provided normative State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scores for neuropsychiatric patients based on data from male veterans. Compared with the normative patients with depressive reaction, the patients with mood disorders in the study reported here had somewhat lower mean pretreatment scores (47.58± 12.73, compared with 54.43±13.02). The pretreatment scores of the patients with psychotic disorders in this study were slightly higher than the scores for the normative patients with schizophrenia (48.47±15.26, compared with 45.70±13.44).

In this study, no significant difference was found between the anxiety change scores after patients participated in animal-assisted therapy and after patients participated in therapeutic recreation. However, this lack of difference could be due to the small number of patients (N=50) who completed all four study measures. A power analysis of the magnitude of differences between the change scores for animal-assisted therapy and therapeutic recreation indicated that larger samples would be needed to achieve an 80 percent power level at an alpha of .05: a sample of 300 patients with psychotic disorders, 125 patients with substance use disorders, and 61 patients with other disorders. For patients with mood disorders, the difference in anxiety change scores was too small for any reasonably sized study to detect a significant difference.

For within-group differences, a significant reduction in anxiety after therapeutic recreation was found only for patients with mood disorders, whereas a significant reduction after animal-assisted therapy was found for patients with mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and other disorders. The size of these reductions was similar to differences reported by Wilson (13) for college students whose anxiety scores were measured under varying levels of stress.

No significant reduction was found in anxiety scores for patients with substance use disorders after either animal-assisted therapy or therapeutic recreation. This lack of difference may be due to the small sample size or due to a relationship between state anxiety and physiological withdrawal that is less amenable to change within one session of animal-assisted therapy or therapeutic recreation.

The reduction in anxiety scores for patients with psychotic disorders was twice as great after animal-assisted therapy as after therapeutic recreation. This finding suggests that animal-assisted therapy may offer patients with psychotic disorders an interaction that involves fewer demands compared with traditional therapies. As Arnold (23) contends, perhaps the therapy dog provides some sense of safety and comfort not found in more traditional inpatient therapies. Alternatively, the dog may provide a nonthreatening diversion from anxiety-producing situations (31). Or perhaps it is the physical touching of the dog that reduces patients' anxiety, as has been reported for other populations (12).

In this study setting, animal-assisted therapy was offered only one day each week. It would be interesting to study the effect of more frequent exposure to determine if the reduced anxiety is partly due to novelty or if increased exposure results in further anxiety reductions. Although some patients in the study remained hospitalized long enough to participate in more than one animal-assisted therapy session, there were not enough such patients to permit investigation of the effect of repeated exposure. Therefore, data from their initial animal-assisted therapy and therapeutic recreation sessions were used for analyses.

It is not possible to determine how much the dog or the owner contributed independently to the reductions in anxiety found in this study. Although the study's purpose was to examine the effect of animal-assisted therapy, further examination of the effect of its components is needed.

Because many owners of therapy dogs volunteer their time to come to psychiatric units, animal-assisted therapy appears to be a cost-effective intervention. However, volunteers may not participate consistently. In this study, a second therapy dog and owner, a potential confounding variable, were introduced after the first owner became ill. Use of nonvolunteers could strengthen future studies by providing more consistent treatment conditions.

Finally, although the results provide evidence of the immediate effect on state anxiety of a single session of animal-assisted therapy, further study is needed to determine if patients' overall level of anxiety is affected. Further studies of the effect of animal-assisted therapy on psychiatry services are needed to replicate the findings from this study and to advance our understanding of the therapeutic benefits of the human-animal interaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Al Best, Ph.D., for his assistance with statistical analysis and Pat Conley, Helen Brown, and Claudette McDaniel for their assistance with data collection.

Dr. Barker is associate professor of psychiatry, internal medicine, and anesthesiology and Dr. Dawson is affiliate assistant professor of biostatistics at the Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University, P.O. Box 980710, Richmond, Virginia 23298. Dr. Barker's e-mail address is [email protected].

|

Table 1. Mean pretreatment, posttreatment, and change scores on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for hospitalized psychiatric patients with various diagnoses who participated in an animal-assisted therapy session or therapeutic recreation

1. Akiyama A, Holtzman JM, Britz VVE: Pet ownership and health status during bereavement. Omega 17:187-193, 1986Google Scholar

2. Rowan AN: Do companion animals provide a health benefit? (edtl). Anthrozoös 4:212, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Serpell J: Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behavior. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 84:717-720, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Siegel JM: Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: the moderating role of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58:1081-1086, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Friedman E, Katcher AH, Lynch JJ, et al: Animal companions and one-year survival of patients after discharge from a coronary care unit. Public Health Reports 95:307-312, 1980Medline, Google Scholar

6. Anderson WP, Reid CM, Jennings GL: Pet ownership and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Medical Journal of Australia 157:298-301, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Davis JH: Animal-facilitated therapy in stress mediation. Holistic Nursing Practice 2:75-83, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Patronek GJ, Glickman LT: Pet ownership protects against the risks and consequences of coronary heart disease. Medical Hypotheses 40:245-249, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Baun M, Bergstrom N, Langston N, et al: Physiological effects of petting dogs: influence of attachment, in The Pet Connection. Edited by Anderson RK. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1984Google Scholar

10. Friedman E, Katcher AH, Thomas SA, et al: Social interaction and blood pressure: influence of companion animals. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 171:461-465, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Katcher AH, Friedman E, Beck AM, et al: Looking, talking, and blood pressure: the physiological consequences of interaction with the living environment, in Our Lives With Companion Animals. Edited by Katcher AH, Beck AM. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1983Google Scholar

12. Vormbrock JK, Grossberg JM: Cardiovascular effects of human-pet dog interactions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 11:509-517, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wilson CC: The pet as an anxiolytic intervention. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:482-489, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Nagengast SL, Baun MM, Leibowitz MJ, et al: The effects of the presence of a companion animal on physiological and behavioral distress in children during a physical examination. Abstracts of the Delta Society Twelfth Annual Conference. Renton, Wash, Delta Society, 1993Google Scholar

15. Barba BE: The positive influence of animals: animal-assisted therapy in acute care. Clinical Nurse Specialist 9:199-202, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Voelker R: Puppy love can be therapeutic, too. JAMA 274:1897-1899, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Beck A: The therapeutic uses of animals. Veterinary Clinics of North America, Small Animal Practice 15:2, 1985Google Scholar

18. Beck A, Katcher A: A new look at animal-assisted therapy. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 184:414-421, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

19. Draper RJ, Gerber GJ, Layng EM: Defining the role of pet animals in psychotherapy. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa 15:169-172, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

20. Searles H: The Non-Human Environment. New York, International Universities Press, 1960Google Scholar

21. Levinson BM: The dog as co-therapist. Mental Hygiene 46:59-65, 1962Medline, Google Scholar

22. Francis G, Turner J, Johnson S: Domestic animal visitation as therapy with adult home residents. International Journal of Nursing Studies 22:201-206, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Arnold JC: Therapy dogs and the dissociative patient: preliminary observations. Dissociation 8:247-252, 1995Google Scholar

24. Barker SB, Barker RT, Dawson KS, et al: The use of the family life space diagram in establishing interconnectedness: a preliminary study of sexual abuse survivors, their significant others, and pets. Individual Psychology, in pressGoogle Scholar

25. Mallon GP: Utilization of animals as therapeutic adjuncts with children and youth: a review of the literature. Child and Youth Care Forum 21:53-67, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Holcomb R, Meacham M: Effectiveness of an animal-assisted therapy program in an inpatient psychiatric unit. Anthrozoös 2:259-264, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Beck A, Seraydarian L, Hunter G: The use of animals in the rehabilitation of psychiatric inpatients. Psychological Reports 58:63-66, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Walsh PG, Mertin PG, Verlander DF, et al: The effects of a "pets as therapy" dog on persons with dementia in a psychiatric ward. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 42:161-166, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Batson K, McCabe BW, Baun MM, et al: The effect of a therapy dog on socialization and physiologic indicators of stress in persons diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, in Animals, Health, and Quality of Life: Abstract Book. Paris, France, AFIRAC, 1995Google Scholar

30. Spielberger CD: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, Calif, Mind Garden, 1977Google Scholar

31. Arkow P: How to Start a Pet Therapy Program. Alameda, Calif, Latham Foundation, 1982Google Scholar