Prevalence of Physical Illness Among Psychiatric Inpatients Who Die of Natural Causes

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The state psychiatric hospital is experiencing an increase in medically sick and aging patients who die of natural causes while hospitalized. This study explored the "medicalization" of the state hospital by examining the prevalence of medical illness and its relationship with psychiatric illness and age among state hospital psychiatric inpatients who died of natural causes—deaths that were not accidents, homicides, or suicides. METHODS: A total of 179 inpatients who died of natural causes at Western State Hospital in Washington State between 1989 and 1994 were studied retrospectively through case file review. Their demographic and institutional characteristics and psychiatric diagnoses were compared with those of others treated at the hospital (N=9,258). The medical diagnoses of patients who died were analyzed by age and psychiatric condition. RESULTS: The patients who died were much older than the other patients treated during the study period. Two-thirds of those who died had organic mental disorders, mostly dementia, whereas only a fifth of the other patients had these disorders. The patients who died had a mean of eight physical illnesses, with a range from none to 21. Circulatory and respiratory conditions were most prevalent, affecting half to two-thirds of patients; these conditions had high rates of comorbidity with organic mental disorders. CONCLUSIONS: The characteristics of the state hospital population and the services provided are shifting in response to mental health reform and new policies on patient self-determination. Increased emphasis on medical care added to traditional psychiatric services will require increased financial and personnel resources.

The state mental hospital has traditionally provided primary psychiatric care and limited medical treatment, routinely referring patients with major physical illnesses to a general hospital. As the state hospital's population declines, approaches to patient care are changing, and patient self-determination policies—the "right to die" and "death with dignity"—offer new options to the residual population of older, difficult-to-manage patients with severe medical needs (1).

This "medicalization" of the state hospital results in high costs for equipment, drugs, and staffing; longer hospital stays; an increasingly aged population; and increasing death rates (2). Even as the patient population and total staff decline, expenditures and professional care staff continue to increase at the state hospital (3).

This paper presents the results of research on the prevalence of physical illness and its relationship with psychiatric illness and aging among psychiatric inpatients who died of natural causes at Western State Hospital. Opened in 1871 at Fort Steilacoom, the facility is one of two state psychiatric hospitals in Washington. As of July 1997, the bed capacity was 1,002. The catchment area is the western half of the state, which includes about 3 million of the state's 5 million inhabitants.

The hospital has four programs: the adult psychiatric unit, the geriatric-medical unit, the legal offender unit, and the program for adaptive living skills. Patients on the adult unit, who are between the ages of 18 and 65, constitute 43 percent of the inpatients. The mean length of stay is two weeks for acute care and six months for extended care. The geriatric-medical unit has 23 percent of the patients, most of whom are older than 60, and a few of whom are younger and have serious medical conditions. The current mean stay is about three years. Ninety-five percent of patients on the adult and geriatric-medical units are civilly committed, and 5 percent are voluntary.

Patients on the legal offender unit, which has 20 percent of the hospital's patients, are admitted for court-ordered evaluations and commitments. They include persons who are found not guilty by reason of insanity or judged not competent to stand trial. The average stay is two and a half years. The program for adaptive living skills, a 180-day transitional residential program, was started in 1984 for patients on less restrictive court orders who are making a transition to the community but do not have readily available placement resources. This unit has 14 percent of the hospital's patients.

Methods

Data were collected retrospectively from case file reviews for 179 inpatients who died of natural causes between 1989 and 1994. Deaths due to accidents, homicides, or suicides were excluded. The final DSM-III-R psychiatric diagnosis and the axis III medical diagnosis were analyzed (4). Although medical illness is not viewed as the cause of psychiatric problems (5), a strong association has been found among patients with many somatic symptoms (6). Further, among mental patients, physical illness is a key contributor to both treatment success and natural death (7).

To assess this relationship, physical illness was categorized in this study according to major ICD-9 codes (8) based on the affected organ without using inclusion or exclusion criteria (9,10,11). Demographic and institutional characteristics of patients who died between 1989 and 1994 were compared with those of all patients treated between 1991 and 1994. For those who died, the interrelationships among psychiatric condition, age, and medical illness were analyzed.

Results

Patient characteristics

The mean±SD age of the 179 patients who died of natural causes during the study period was 73±15.03 years, with a range of 19 to 101 years. For the 9,258 patients treated at the hospital between 1991 and 1994, the mean age was 43±15.99 years (range=18 to 98 years).

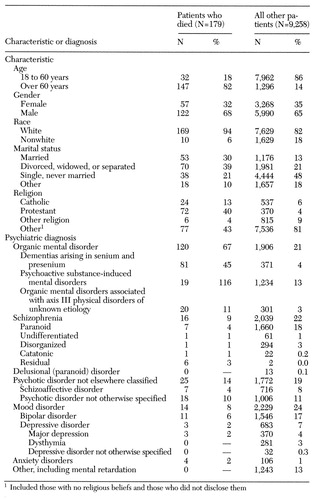

As Table 1 shows, 82 percent of patients who died of natural causes were over 60 years old, compared with 14 percent of all patients treated. Gender proportions were similar in the two groups, but the majority of natural deaths occurred among Caucasians, patients belonging to any religion, and those currently or previously married. The mean length of stay of patients who died was twice that of the other patients (1.61±1.38 years versus .72±1.27 years).

The total natural death rate was 1 percent in 1989, .89 percent in 1990, 1.01 percent in 1991, .64 percent in 1992, 1.71 percent in 1993, and 2.36 percent in 1994. Annual admissions declined from 2,911 in 1989 to 1,759 in 1994. The age-related admission trend shows an increase in new admissions of patients over age 60, from 4 percent a year in 1989 to more than 12 percent in 1994. Considering the decline in overall admissions and the longer stays, the rate of accumulation of older patients is considerable.

Psychiatric diagnoses

Table 1 also shows psychiatric diagnoses at death or discharge for the two groups. Of the patients who died of natural causes, 120 (67 percent) had organic mental disorders (12). In comparison, only 21 percent of all patients who were treated had organic mental disorders. Psychotic disorders not otherwise specified affected 14 percent of those who died; schizophrenia, 9 percent; and mood disorders, 8 percent. For all other patients, mood disorders affected 24 percent; schizophrenia, 22 percent; and psychotic disorders not otherwise specified, 19 percent.

Twenty-eight percent of all deaths from natural causes in 1989 were of patients between the ages of 18 and 60, declining to 16 percent in 1994. Deaths of those over age 60 increased from 72 percent of the total in 1989 to 84 percent in 1994. Although standardized mortality ratios reported for younger psychiatric patients are higher than national norms (12,13), older patients seem to present a higher mortality risk (7,,14).

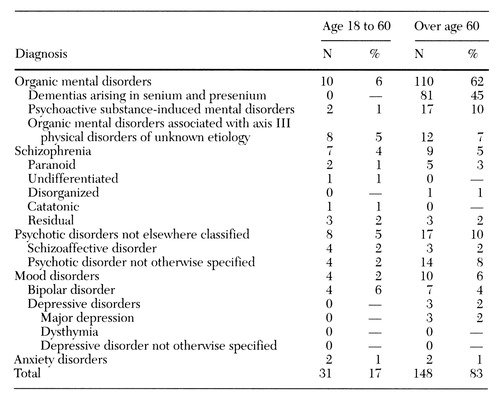

As Table 2 shows, during the study period, 83 percent of deaths from natural causes occurred among patients over 60 years old. Of the 148 patients in this age group who died, 110 (74 percent) had organic mental disorders. All dementia patients who died of natural causes were over age 60.

Medical diagnoses

A primary index of physical illness is the patient's total number of medical disorders. The 179 patients who died had a total of 1,437 physical conditions. The mean number of disorders per patient in this group was eight, with a median and mode of eight and a range of none to 21. Twenty-seven percent of the patients who died had from four to six medical disorders, 37 percent had from seven to nine disorders, 17 percent had from ten to 12 disorders, and 11 percent had 13 or more disorders. Although other studies have pointed out the high comorbidity of physical illness in elderly psychiatric patients (6,11,15), the physical conditions observed in this group were unusually numerous.

The mean±SD number of medical conditions of those between the ages of 18 and 60 was 6.9±3.2, compared with 8.26±3.5 for those over age 60. The difference was highly significant (χ2=73.9, df=18, p<.001).

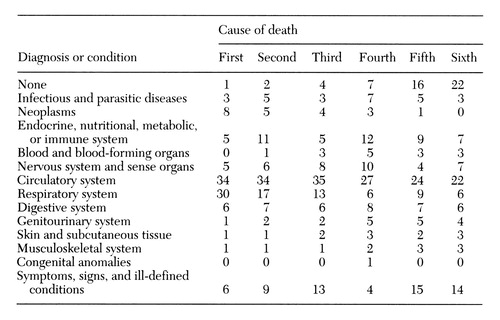

Table 3 lists the medical diagnoses and debilitations at death of the 179 patients. The rankings from first to sixth represent the order in which they were diagnosed at the hospital; the most severe conditions are listed first. Ninety-eight percent of patients had two or more serious problems, 96 percent had three or more, 93 percent had four or more, 84 percent had five or more, and 78 percent had six or more. Problems of the circulatory and respiratory systems were the most prevalent (16). From 34 to 35 percent of the first three diagnoses at death were circulatory illnesses; in 22 percent of the deaths, they were listed as the sixth diagnosis. In 30 percent of the deaths, respiratory problems were listed as the first diagnosis, and in 6 percent the sixth diagnosis. Together, circulatory and respiratory illnesses accounted for 64 percent of the first diagnosis at death and were the sixth diagnosis in 28 percent of the deaths. Other serious conditions leading to death were neoplasms (cancers) and digestive, neurological, and endocrine illnesses.

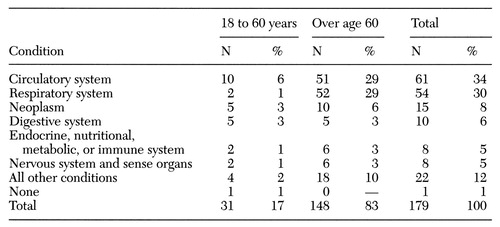

Table 4 shows the relationship between age and major medical conditions among the patients who died. Among the older patients who died, circulatory and respiratory problems were the most severe, each affecting about a third of the patients. Thirty-nine percent of the patients in the 18- to 60-year age group who died had one or both of the conditions, compared with 70 percent of those over age 60.

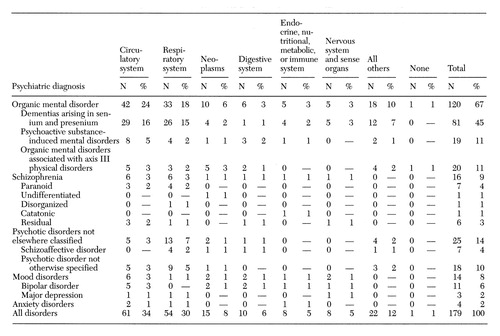

Organic mental disorders, which affected 67 percent of the patients who died, had a high rate of comorbidity with circulatory and respiratory conditions, which accounted for 64 percent of the first diagnosis at death. As shown in Table 5, among patients who had organic mental disorders, 24 percent had a circulatory condition, and 18 percent had a respiratory condition. Thus 42 percent of the patients who died had an organic mental disorder and at least one of these two types of conditions. Patients with dementia were the largest subgroup of those with psychiatric disorders.

Discussion

A 1989 Washington State statute, the Mental Health Reform Law (17), established regional support networks to administer community programs that provide locally based services to help mentally ill people "retain a respected and productive position in the community." The reform had the intended result of reducing the size of the inpatient population. However, in diverting higher-functioning patients to community programs, it produced an unanticipated effect—a relative increase in high-risk, old, and medically fragile patients at Western State Hospital who have more complicated conditions than younger patients and who are more difficult to treat both psychiatrically and medically.

In addition to the reform, a policy change by the Washington Aging and Adult Services Administration also contributed to the increase of older adults at the state hospital. The change resulted in declines in admissions of Medicare and Medicaid patients to nursing homes, and it limited the number of private-pay patients already admitted to nursing homes who attempt to adjust their pay status to Medicaid or Medicare. A number of these nursing home clients ended up at the state hospital. Among the 179 patients who died, 74 (41 percent) were referred to the hospital from nursing homes, which was partly a result of this policy change.

The influence of medical care on psychiatric treatment outcome differs for young and old patients (18). For older patients, such as the majority of patients in the group in this study who died of natural causes, special care provided by hospitalization may result in improvement in functioning and quality of life even for low-functioning demented patients (19). However, outcome is affected when physical symptoms are masked by psychiatric illness (20,21), and the extra effort required for diagnosis may result in longer hospital stays (22,23) and a higher cost of care.

Elderly psychiatric patients and patients with organic mental disorders present the greatest risk of comorbid physical illness (12,24), with high prevalence rates of such illnesses (11,25). Lung and respiratory illnesses are the most common (13,14). Our findings are consistent with those observations. However, the number of somatic conditions noted among the elderly patients in this study was substantially higher than in other studies (6,11,15).

Consistent with the Patient Self Determination Act (26), the Western State Hospital advance directives include living wills that address the right to die and death with dignity. The right-to-die policy is a prior authorization by a competent patient or surrogate for withholding or withdrawing life-prolonging treatment and preventing the use of invasive procedures at a future date when the patient is incapable of making that decision (such as in a terminal or permanently unconscious state), unless it affects a compelling state interest. This policy appears to hasten death where it might have been delayed. Also, for older patients both mean age at death and length of hospital stay before death might decline (22). In a facility with a high proportion of elderly patients, a high death rate might be sustained even with declining admissions.

The do-not-resuscitate order, also referred to as death with dignity, preauthorizes withholding cardiopulmonary resuscitation when a respiratory or cardiac arrest occurs, except for an accident or suicide attempt. Nonetheless, oxygen administration, oropharyngeal suction, and the Heimlich maneuver would be performed. Early in the 1990s few elderly patients used advance directives (27). However, more recent studies have noted a high rate of do-not-resuscitate orders among critical care patients over age 75 regardless of illness (28). Even though the purpose of such orders is to preserve an individual's dignity, the fact that age is a primary consideration in their use may signal an undue influence on death. Like the right-to-die policy, this policy will continue to influence deaths, and both mean age and length of stay may decline.

In Oregon advance directives are reported to honor patients' wishes, to empower them, and to enrich the informed consent process (29). At Western State Hospital advance directives facilitate hospice-like treatment, which offers patients satisfactory choices that appear to be responsive to their needs.

Conclusions

As the state mental hospital continues to reduce its population in response to expanding community programs (30,31), it has also been struggling with the crisis of defining its changing identity (32,33). The older, medically sick psychiatric patient continues to place costly demands for specialized "residual" services of acute medical care and hospice management (32,34,35,36). These demands are shifting the focus of the state hospital in a new direction: how to deal with increasing medical problems of older adults who often have terminal illnesses. Meeting the needs of this task in terms of financial resources, equipment, and personnel poses serious challenges to the survival of the state hospital (37). These challenges may be different from one situation to the next or even periodically. However, it is clear that they are defining a new role and direction for the state mental hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Diane Pearson and Sharon Abele-Hall of the Washington Institute; Dennis McBride, Ph.D., Georgette Armstrong, and Ken Kirkwood of the quality assurance section of Western State Hospital; and Robert Putnam, Melinda Small, and Celeste Poechhacker of the medical records section of Western State Hospital.

Dr. Kamara is clinical assistant professor and research manager and Dr. Peterson is clinical professor and director at the Washington Institute for Mental Illness Research and Training, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, 9601 Steilacoom Boulevard, S.W., Tacoma, Washington 98498-7213 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Dennis is chief executive officer of Western State Hospital in Tacoma.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and psychiatric diagnoses at death or discharge of state hospital patients who died of natural causes between 1989 and 1994 and all other patients treated at the hospital between 1991 and 1994

|

Table 2. Psychiatric diagnoses of 179 state hospital patients who died of natural causes between 1989 and 1994, by age group

|

Table 3. Medical diagnoses or conditions listed for 179 state hospital patients who died, in order of importance of the condition as a cause of death, by percentage of patients

|

Table 4. Major medical conditions at death among 179 state hospital patients who died, by age group

|

Table 5. Co-occurrence of psychiatric diagnoses and medical illness among 179 state hospital patients who died

1. White L, Parella M, McCrystal SJ, et al: Characteristics of elderly psychiatric patients retained in a state hospital during downsizing: a prospective study with replication. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 12:474-480, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Burvill PW, Hall WD: Predictors of increased mortality in elderly depressed patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 9:219-227, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Witkin MJ, Atay J, Manderscheid RW: Trends in state and county mental hospitals in the US from 1970 to 1992. Psychiatric Services 47:1079-1081, 1996Link, Google Scholar

4. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

5. Maricle R, Leung P, Bloom JD: The use of DSM-III axis III in recording physical illness in psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:1484-1486, 1987Link, Google Scholar

6. Kisely SR, Goldberg DP: Physical and psychiatric comorbidity in general practice. British Journal of Psychiatry 169:236-242, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Langley AM: The mortality of mental illness in older age. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology 5:103-112, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

8. ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, 9th ed: Clinical Modification, 4th ed, vols 1 and 2. Los Angeles, Product Management Information Corp, 1993.Google Scholar

9. Sox HC, Koran LM, Sox CH, et al: A medical algorithm for detecting physical disease in psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1270-1276, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Koran LM, Sox HC, Marton KI, et al: Medical evaluation of psychiatric patients: I. results in a state mental health system. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:733-740, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Sheline YI: High prevalence of physical illness in a geriatric psychiatric inpatient population. General Hospital Psychiatry 12:396-400, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D: Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:1356-1363, 1996Link, Google Scholar

13. Amaddeo F, Bisoffi G, Bonizzato P, et al: Mortality among patients with psychiatric illness: a ten-year case register study in an area with a community-based system of care. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:783-788, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Licht RW, Mortensen PB, Gouliaev G, et al: Mortality in Danish psychiatric long stay patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 87:336-341, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kovar M: Health of the elderly and use of health services. Public Health Report 92:9-19, 1977Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kendrick T: Cardiovascular and respiratory risk factors and symptoms among general practice patients with long-term mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 169:733-739, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. State Senate Bill 5400: County-Based Mental Health Services. Laws of Washington, 1989 (Chapter 205). Olympia, Washington Legislature, 1989Google Scholar

18. Weingarten CH, Rosoff LG, Eisen S, et al: Medical care in a geriatric psychiatry unit: impact on psychiatric outcome. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 30:738-743, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Bakey AA, Kunick ME, Orengo CA, et al: Outcome of psychiatric hospitalization for very low-functioning demented patients. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 10:55-57, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Hall RCW, Gardner ER, Stickney SK, et al: Physical illness manifesting as psychiatric disease. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:989-995, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kisely SR, Goldberg DP: The effect of physical ill health on the course of psychiatric disorder in general practice. British Journal of Psychiatry 170:536-540, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sharma SD, Kurien C: The length of stay of psychiatric inpatients. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 29:315-323, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

23. Schubert DSP, Yokely J, Sloan D, et al: Impact of the interaction of depression and physical illness on a psychiatric unit's length of stay. General Hospital Psychiatry 17:326-334, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Suagstad LF, Odegard O: Mortality in psychiatric hospitals in Norway, 1950-1974. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 59:431-477, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Maguire GP, Granville-Grossman KL: Physical illness in psychiatric patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 115:1365-1369, 1968Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA 1990), Public Law No 101-508, Sec 4206 (Medicare) and Sec 4751 (Medicaid), 1990Google Scholar

27. High DM: Why are elderly people not using advance directives? Journal of Aging and Health 5:497-515, 1993Google Scholar

28. Boyd K, Teres D, Rapoport J, et al: The relationship between age and the use of DNR orders in critical care patients. Archives of Internal Medicine 156:1821-1826, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Backlar P, McFarland BH: A survey on use of advance directives for mental health treatment in Oregon. Psychiatric Services 47:1387-1389, 1996Link, Google Scholar

30. Okin LR: Expand the community care system: deinstitutionalization can work. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:742-745, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

31. Okin LR: Testing the limits of deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Services 46:569-574, 1995Link, Google Scholar

32. Bachrach LL: The future of the state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:467-474, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Bachrach LL: The state of the state mental hospital in 1996. Psychiatric Services 47:1071-1078, 1996Link, Google Scholar

34. Gralnick A: Build a better state hospital: deinstitutionalization has failed. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:738-741, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

35. Semke J, Fisher WH, Goldman HH, et al: The evolving role of the state hospital in the care and treatment of older adults: state trends, 1984-1993. Psychiatric Services 47:1082-1087, 1996Link, Google Scholar

36. Saravay SM: Medical and depressive comorbidity in psychiatric patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 17:321-323, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Thompson JW, Belcher JR, DeForge BR, et al: Changing characteristics of schizophrenic patients admitted to state hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:231-235, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar