The Role of Religion in the Well-Being of Older Adults With Schizophrenia

Religion is thought to assist in the recovery of persons with schizophrenia ( 1 ). Among older adults, religion has been associated with enhanced well-being ( 2 ). Because older persons tend to be more religious ( 3 ), it is plausible that religion may have a greater impact on the well-being of older adults with schizophrenia than on younger adults with schizophrenia. However, despite an anticipated doubling of the older population with schizophrenia over the next two decades ( 4 ), the impact of religion in this age group has been largely neglected. This study examined the role of religion on the clinical and social well-being of older adults (55 and older) with schizophrenia.

Religion has been conceptualized in various ways. Spirituality refers to viewing one's self as part of a larger spiritual force—for example, the sacred, transcendent, or ultimate reality ( 1 , 5 , 6 ). Religiosity concerns how the experience of a transcendent being is expressed through a social organization ( 7 ). Religiousness is a broader concept that comprises an extrinsic component, such as religious attendance and behavior, and an intrinsic or subjective component that includes spirituality and religious belief and knowledge of, attitudes toward, and salience (perceived importance) of religion ( 8 ). In this study we used the three dimensions of religiousness most commonly identified in the literature that incorporates intrinsic and extrinsic elements: salience, frequency of formal religious activities, and religion as a coping strategy ( 8 , 9 , 10 ).

In studies of older persons in general, religiousness has been associated with greater physical well-being, self-esteem, coping, and life satisfaction ( 11 ). These outcomes are thought to be due to its value as a psychological and social resource—that is, it may have a positive impact on life stressors and the ability to provide meaning and coherence to life and communal support ( 6 , 12 ). Despite evidence for its beneficial influences, religiousness may sometimes have negative effects ( 13 ).

Studies on religiousness and schizophrenia have focused primarily on religious delusions and hallucinations, but recently, the role of religion as a mediator of health and well-being has received attention ( 14 ). Investigators have found both positive and negative effects of religious coping in schizophrenia ( 6 ). For example, a Swiss study of 115 patients with schizophrenia found that 45% of patients considered religion to be the most important element in their lives, and religious coping induced positive effects (for example, hope, meaning, and purpose) and negative effects (for example, despair and suffering) in 71% and 14% of the sample, respectively ( 15 ). More studies are needed to determine under which circumstances religion will have a beneficial or pernicious role ( 16 ).

The World Health Organization considers religion to be an important element in the evaluation of quality of life ( 17 ). Huguelet and Mohr ( 16 ) found that continuous positive religious coping can improve outcomes in schizophrenia, including quality of life, and they argued that any model examining the impact of religion must consider its ability to increase support or relieve stress. Pearlin and colleagues' Stress Process Model ( 18 ) is well suited for this type of analysis because it examines stressors that affect quality of life and the role that various buffers, such as religiousness, social support, and coping strategies, have in modifying stress. In this study, we used an adaptation of this model to explore the effects of religion on life quality.

We addressed the issues described above by using a large, multiracial, urban sample of persons aged 55 and older with schizophrenia. We examined the following questions. First, are older persons with schizophrenia different from their age peers in the general community with respect to religiousness? Second, what is the relationship between religiousness and psychotic symptoms among older persons with schizophrenia? And finally, for older persons with schizophrenia, how does religiousness affect quality of life in the Stress Process Model?

Methods

Sample

Details of the study methods and instruments and the rationale for the age criteria are provided elsewhere ( 19 ). Briefly, during the period 2002–2004 we recruited participants aged 55 and older living in the community with early-onset schizophrenia (onset before age 45) using a stratified sampling method in which we attempted to interview approximately half the participants from outpatient clinics and day programs and the other half from supported community residences in New York City. Inclusion was based on a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder that was given by clinical agency staff and by a lifetime illness review adapted from Jeste and associates ( 20 ). We excluded persons with moderate or severe cognitive impairment.

We recruited a community comparison group using Wessex Census STF3 files for Kings County (Brooklyn), New York. We used randomly selected block groups as the primary sampling unit. An effort was made to interview all persons aged 55 and older in a selected block group by knocking on doors. In order to enhance response rates, participants from the selected block group were also recruited at senior centers, at churches, and through personal references. We excluded persons with a history of treatment for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. The study had institutional review board approval, and we obtained written informed consent.

The rate of declining to participate in the study was 7% (N=15 of 213) in the schizophrenia group and 48% (N=190 of 396) in the community group. The schizophrenia group consisted of 198 persons with schizophrenia, among whom 39% (N=77) were living independently in the community and 61% (N=121) were living in supported community residences. We initially matched the original community comparison group (N=206) with the schizophrenia group by race, then gender, and as closely as possible by age; the final sample comprised 113 persons.

Measures

We used an adaptation of Pearlin and colleagues' Stress Process Model ( 18 ) in order to situate religiousness within a framework that would allow for the assessment of its direct and buffering effects on quality of life. The model consisted of nine primary and intrapsychic stress variables (measures of daily functioning, physical illness, financial strain, lifetime traumatic events, acute stressors, depression, self-esteem, depression, and positive and negative symptoms) and three coping variables (religiousness, the extent of use of cognitive coping strategies, and the number of confidantes). Primary and intrapsychic stressors were selected according to their theoretical importance or their having been identified in the literature as having an impact on quality of life ( 17 , 21 ). Five demographic variables were used as covariates: age, gender, race (white versus nonwhite), education, and residential type (supported or independent). The dependent variable was quality of life.

The following instruments were used to generate the variables in the analysis: the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) ( 22 ); the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) ( 23 ); the Financial Strain Scale ( 24 ); the Multilevel Assessment Inventory ( 25 ), from which we derived a summed score of the number of physical illnesses; as well as the nine-item Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale (IADL); the Cognitive Coping Scale, which was derived from coping items proposed by Pearlin and coauthors ( 18 ); the Lifetime Trauma and Victimization Scale ( 26 ); the Self Esteem Scale ( 27 ); the Network Analysis Profile ( 28 ); the Acute Stressors Scale ( 29 ); and the Quality of Life Index (QLI) ( 30 ). The religiousness scale, which was developed for this study, is based on seven items encompassing the three principal domains of religiousness identified in the literature (salience, formal religious activities, and coping). The possible total score ranges from 1 to 25, with higher scores indicating higher levels of religiousness.

The internal reliability (Cronbach's alpha) scores of the scales were as follows: CES-D, .88; PANSS positive scales, .83; PANSS negative scales, .78; Acute Stressors Scale, .88; Financial Strain Scale, .79; IADL scale, .77; Cognitive Coping Scale, .78; Self-Esteem Scale, .82; religiousness scale, .75; and QLI, .97. All scales attained recommended alphas of .60 or higher ( 31 ). The intraclass correlations ranged from .79 to .99 on the various scales.

Data analysis

To compare the schizophrenia and the community groups we used the Mann-Whitney U test. For the schizophrenia group, we used a stepwise hierarchical linear regression analysis to assess the impact of the religiousness variable on quality of life in the Stress Process Model. Variables were entered in five steps in the following order: demographic variables, stress variables, scores on the religiousness scale, other buffering variables, and an interaction term between scores on the religiousness scale and the stress variables. To examine the mediating effects of religiousness on various stress variables associated with the QLI, we examined whether the religiousness scale had any effect in reducing the beta values of the significant stress variables. We examined moderating effects by using the product terms between the religiousness scale and each of the significant stress variables. A centroid transformation was used to avoid problems with collinearity. The dependent variable was normally distributed, and there was no evidence of collinearity among the independent variables.

Results

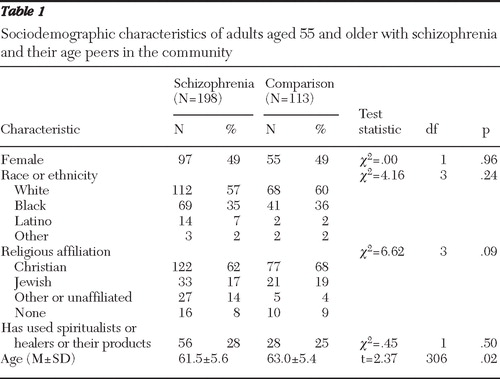

There were no significant differences between the group with schizophrenia and the group in the community by gender, race, religious preferences, or use of spiritualists or healers ( Table 1 ). There was a small difference in age (1.5 years) between the two groups that attained statistical significance. Both groups were in the same median personal income category ($7,000–$12,999).

|

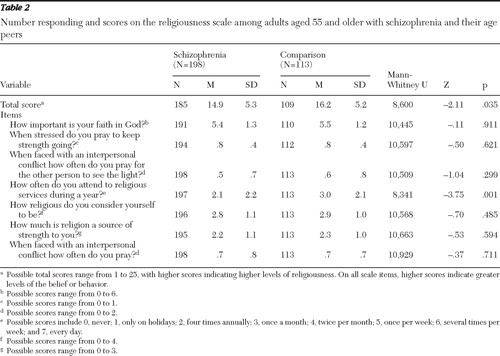

Older persons with schizophrenia scored significantly lower on religiousness than their age peers in the community, although the absolute difference was only 1.3 points on a 25-point scale ( Table 2 ). Of note, 59% (N=115) of the schizophrenia group and 60% (N=68) of the community comparison group responded "a great deal" to the item asking how much religion or God was "a source of strength" to them (score of 3). Among the seven items in the religiousness scale, the two groups significantly differed only on frequency of attending religious services, with community residents participating more frequently than the schizophrenia group—that is, four times per year versus about once a month ( Table 2 ).

|

With respect to psychosis and religiousness among persons with schizophrenia, although there was an association between greater religiousness and lower PANSS positive scores, this did not attain significance. Thirty-two percent (N=64) of the sample with schizophrenia reported auditory hallucinations. Among those hearing voices, 27% (N=17) attributed them to God or other supernatural causes, 25% (N=16) attributed them to biomedical or clinical causes, 30% (N=19) attributed them to miscellaneous causes, and 20% (N=13) weren't sure. Nine percent (N=17) of the schizophrenia sample reported specific auditory hallucinations from God (N=13, 7%), the devil (N=2, 1%), or both (N=2, 1%). Among those hearing voices of God, 11 (85%) said they were pleasant, one (8%) said they were unpleasant, and one (8%) said they were both pleasant and unpleasant. In a hierarchical regression analysis, we found a significant inverse association between the PANSS positive scores and the QLI scores ( β =-.21, t=-2.91, df=180, p=.004). When religiousness was added to the analysis, there was essentially no change (that is, a .01 decline in the beta value) in the association between the PANSS positive scores and the QLI scores. When the interactional term (with centroid transformation) of religiousness × PANSS positive scores was added to the analysis, we found no significant association with the QLI scores.

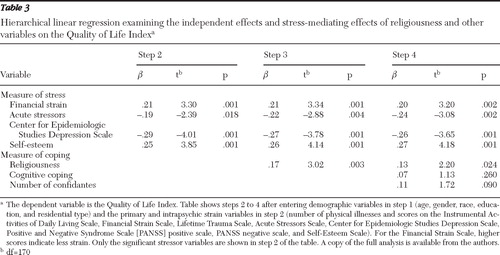

Next, we examined the relationship between stressors, religiousness, and quality of life in the schizophrenia group. As shown in Table 3 , in a hierarchical regression analysis, we found that four of the nine primary and intrapsychic stressors in the model—financial strain, acute stressors, depression, and self-esteem—were significantly associated with the QLI scores. (The PANSS positive score was no longer significantly associated with the QLI scores when entered with other variables.) When scores on the religiousness scale were added to the model, we found a significant association between religiousness and the QLI scores. However, the addition of scores on the religiousness scale did not diminish the beta values of the stress variables that had been significantly associated with the QLI scores in step 2. After two other mediating variables (cognitive coping techniques and number of confidantes) were added, the association of the religiousness scale scores with the QLI scores remained significant. Finally, we assessed the moderating effects of religiousness with each of the significant stress variables by separately testing the significance of the interactional term in the model. None of the following interactional terms were significant: Financial Strain Scale × religiousness scale, Acute Stressors Scale × religiousness scale, CESD × religiousness scale, and Self-Esteem Scale × religiousness scale.

|

In order to examine the potential role of religion to cope with alcoholism, we conducted a post hoc analysis and found no significant correlations between scores on the religiousness scale and current CAGE scores or past CAGE scores.

Discussion

With respect to whether there would be differences in religiousness scores between older persons with schizophrenia and their age peers in the community, we found the latter had significantly higher levels of religiousness, although the absolute differences were very modest. Moreover, the differences could be attributed largely to formal religious attendance—that is, the community group had roughly three times more frequent attendance. Thus attendance differed between the groups, but older adults with schizophrenia and their age peers were equally likely to report using religion as a coping strategy and to view it as important in their lives.

Our findings were similar to those of a Swiss study with a broad age range of respondents in which persons with schizophrenia had about half the level of group religious attendance as their the counterparts without psychiatric disorders ( 32 ). Huguelet and Mohr ( 16 ) concluded that although a majority of persons with psychotic symptoms use religious coping, many pray alone and are often not involved in religious communities. Huguelet and Mohr ( 33 ) observed that such persons "repeat in religious settings what happens in other areas of their lives," presumably because of difficulties creating and maintaining social networks. Fallot ( 6 ) noted that religious communities can sometimes be rejecting for persons with schizophrenia because of their difficulties meeting expectations in behaviors, dress, or financial support.

With respect to the second question concerning the relationship between psychotic symptoms and religiousness, although persons with schizophrenia who had greater levels of religiousness had lower PANSS positive scores, this association was not significant. We also found that religiousness had no mediating or moderating effects on the relationship between quality of life and the PANSS positive scores among persons with schizophrenia. These findings are somewhat perplexing because previous literature had indicated that a large proportion of persons with schizophrenia use religion to cope with their daily symptoms ( 5 ), although it may be less often used for coping with the psychotic symptoms per se. For example, Huguelet and Mohr ( 16 ) believe that religious coping works primarily by providing a positive sense of self, guidelines for interpersonal behavior, and resources to cope with their symptoms. Moreover, in our sample, levels of psychotic symptoms were fairly low (N=125, or 63%, scored below 4 on all of the PANSS positive items), and consequently, any relationship between religion and psychotic symptoms may have been attenuated.

With respect to the last question—the role religiousness plays in the Stress Process Model—we found that religiousness had no mediating or moderating effects on the four stressors found to be associated significantly with the QLI scores. However, religiousness was associated with a significant, albeit modest, 2.4% increase in the explained variance in the QLI scores. Even after the addition of other mediating variables, such as the number of confidantes and cognitive coping strategies, religiousness retained an independent effect on the QLI scores. Thus the benefit of religiousness in our sample was due to its independent, additive effects on life quality rather than its impact on stressors. Because our data are cross-sectional, this finding must be interpreted cautiously because it is possible that higher quality of life may promote greater religiousness.

Although the evidence for the independent effects of religiousness on the physical well-being of older adults has been overwhelmingly positive, the evidence for its independent effects on psychiatric well-being has been less clear. Strawbridge and coauthors ( 34 ) have pointed to evidence both for and against a buffering effect for religiousness on stressors that affect psychiatric well-being of older persons, which they attributed to the differences in the types of stressors that were involved. Our findings were consistent with an independent effect of religiousness on quality of life, and the absence of any buffering effects may also reflect differences from other studies in types of stressors examined, the measure of religiousness, or the outcome variable.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the role of religion among older adults with schizophrenia. Our study has several strengths, including a large multiracial sample, a community comparison group, a psychometrically reliable measure of religiousness, and the use of a theoretical model to assess the role that religiousness plays in the Stress Process Model of quality of life. However, our study is limited by the use of cross-sectional data that precludes the determination of causality between religiousness and other variables, it is confined to one geographical area, there was a low participation rate in the community sample (52%), and the multiple comparisons increase the possibility of a type I error. Nevertheless, because this is an exploratory study, we wished to avoid type II errors, especially in the interpretation of the regression analysis. Finally, the religiousness measure, although having adequate reliability and content validity, will require further validation.

Conclusions

This study found that persons with schizophrenia have lower levels of religiousness than their age peers, although this was primarily due to differences in the rates of formal religious attendance. It also found that religiousness was not significantly associated with psychotic symptoms, nor did it have any buffering effects on the relationship between psychosis and quality of life. And finally, this study found that religiousness had a significant, albeit modest, independent additive effect on quality of life and that it did not have any buffering effects on the four stressors that were significantly associated with quality of life.

Mental health professionals have been found to be much less religious than their patients ( 1 ), and often they are not aware of their patients' religious involvement ( 32 ). Such blind spots may diminish cultural competence ( 1 , 35 ). As our findings suggest, clinicians may overlook a therapeutically important agent.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grants SO6-GM-74923 and SO6-GM-54650 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The authors thank Community Research Applications and Paul M. Ramirez, Ph.D., for their assistance.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Corrigan P, McCorkle B, Schell B, et al: Religion and spirituality in the lives of people with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 39:487–499, 2003Google Scholar

2. Fry PS: Religious involvement, spirituality and personal meaning for life: existential predictors of psychological wellbeing in community-residing and institutional care elders. Aging and Mental Health 4:375–387, 2000Google Scholar

3. Levin J: Religion; in The Encyclopedia of Aging. Edited by Schulz R, Noelker LS, Rocwood K, et al. New York, Springer, 2006Google Scholar

4. Cohen CI, Vahia I, Reyes P, et al: Schizophrenia in later life: clinical symptoms and well-being. Psychiatric Services 59:232–234, 2008Google Scholar

5. Fallot RD: Spirituality and religion in recovery: some current issues. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 30:261–270, 2007Google Scholar

6. Fallot RD: Spirituality and religion; in Clinical Handbook of Schizophrenia. Edited by Mueser KT, Jeste DV. New York, Guilford, 2008Google Scholar

7. Piedemont RL: Personality, spirituality, religiousness, and the personality disorders; in Religion and Spirituality in Psychiatry. Edited by Huguelet P, Koenig HG. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2009Google Scholar

8. Zuraida NZ, Ahmad HS: Religiosity and suicide ideation in clinically depressed patients. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry 16:12–15, 2007Google Scholar

9. Pickard JG: The relationship of religiosity to older adults' mental health service use. Aging and Mental Health 10:290–297, 2006Google Scholar

10. Baetz M, Griffin R, Bowen R, et al: The association between spiritual and religious involvement and depressive symptoms in a Canadian population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192:818–822, 2004Google Scholar

11. Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, et al: Religious coping and depression among elderly, hospitalized medically ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1693–1700, 1992Google Scholar

12. Mohr S, Gillieron C, Borras L, et al: The assessment of spirituality and religiousness in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 195:247–253, 2007Google Scholar

13. Huguelet P, Mohr S, Jung V, et al: Effect of religion on suicide attempts in outpatients with schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorders compared with inpatients with non-psychotic disorders. European Psychiatry 22:188–194, 2007Google Scholar

14. Mohr S, Huguelet P: The relationship between schizophrenia and religion and its implications for care. Swiss Medical Weekly 134:369–376, 2004Google Scholar

15. Mohr S, Brandt PY, Borras L, et al: Toward an integration of spirituality and religiousness into the psychosocial dimension of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1952–1959, 2006Google Scholar

16. Huguelet P, Mohr S: Religion/spirituality and psychosis; in Religion and Spirituality in Psychiatry. Edited by Huguelet P, Koenig HG. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2009Google Scholar

17. WHOQOL and Spirituality, Religiousness, and Personal Beliefs: Report of WHO Consultation. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1998Google Scholar

18. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, et al: Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 30:583–594, 1990Google Scholar

19. Bankole AO, Cohen CI, Vahia I, et al: Factors affecting quality of life in a multiracial sample of older persons with schizophrenia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 15:1015–1023, 2007Google Scholar

20. Jeste DV, Symonds LL, Harris MJ, et al: Nondementia nonpraecox dementia praecox? Late-onset schizophrenia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 5:302–317, 1997Google Scholar

21. Borge L, Martinsen EW, Ruud T, et al: Quality of life, loneliness, and social contact among long-term psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services 50:81–84, 1999Google Scholar

22. Radloff LS: The Centre for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale: a self-report depression for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements 3:385–401, 1977Google Scholar

23. Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale User's Manual. North Tonawanda, NY, Multi-Health Systems, 1992Google Scholar

24. Pearlin NJ, Menaghan EG, Leiberman MA, et al: The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22:337–356, 1981Google Scholar

25. Lawton MP, Moss M, Fulcomer M, et al: Research and service-oriented multilevel assessment instrument. Gerontology 37:91–99, 1982Google Scholar

26. Cohen CI, Ramirez M, Teresi J, et al: Predictors of becoming redomiciled among older homeless women. Gerontologist 37:67–74, 1997Google Scholar

27. Rosenberg M: Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1965Google Scholar

28. Sokolovsky J, Cohen CI: Toward a resolution of methodological dilemmas in network mapping. Schizophrenia Bulletin 7:109–116, 1981Google Scholar

29. Chatters LM: Health disability and its consequences for subjective stress; in Aging in Black America. Edited by Jackson JS, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar

30. Ferrans CE, Powers MJ: Quality of Life Index: development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing Science 8:15–24, 1985Google Scholar

31. Nunnally JC: Psychometric Theory. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1967Google Scholar

32. Huguelet P, Mohr S, Borras L, et al: Spirituality and religious practices among outpatients with schizophrenia and their clinicians. Psychiatric Services 57:366–372, 2006Google Scholar

33. Huguelet P, Mohr S: Conclusion: summary of what clinicians need to know; in Religion and Spirituality in Psychiatry. Edited by Huguelet P, Koenig HG. New York, Cambridge University Press, 2009Google Scholar

34. Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Cohen RD, et al: Religiosity buffers effects of some stressors on depression but exacerbates others. Journal of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 53:S118–S126, 1998Google Scholar

35. Hill PC, Pargament KI, Hood RW, et al: Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 30:51–77, 2000Google Scholar