Health Insurance Coverage Among Persons With Schizophrenia in the United States

Schizophrenia is a chronic illness with a significant economic impact to the U.S. health care system. In 2002 excess direct health care costs for persons with schizophrenia in the United States were estimated to be $22.7 billion ( 1 ). Health insurance is especially important for persons with schizophrenia because they not only require comprehensive health services to treat their psychiatric symptoms over the life course, but they also are at greater risk of a number of general medical diseases and premature death.

Despite these considerations, health insurance coverage is not well characterized for this population. Previous studies have relied on persons who were institutionalized or regularly using psychiatric clinic-based health services ( 2 ), data from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) ( 3 ), or Medicaid or Medicare claims data ( 4 ). Because much of the literature focuses on one health care insurer at a time, comparison of health services across insurance systems is limited.

On the basis of these considerations, the objective of this study was to estimate the rates of insurance coverage among the civilian noninstitutionalized population with schizophrenia in the Unites States and to assess whether basic access to health care varied across health insurance categories. This information is essential to help guide decision makers as they allocate resources for health services for this vulnerable population.

Methods

We conducted an analysis of data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Household Component, made publicly available by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The Household Component of the MEPS is a nationally representative household survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. The survey collects data from a subsample of the U.S. National Health Interview Survey and uses a stratified and clustered random sample with weights that produce nationally representative estimates for health insurance coverage, as well as other health-related demographic and socioeconomic variables ( 5 ). Households are interviewed five times over a two-year period. At various interviews, respondents are asked questions about insurance status as of December 31 of each year, in addition to questions relating to health care services. Individual respondents are issued both a household number and an individual number within their household, which when combined provide an individual-level identifier.

Persons were included in the analytic sample if they were older than 17 years and were identified as having schizophrenia by respondent report. We pooled years 2002 through 2006 to enhance our ability to analyze the subgroup of people with schizophrenia. To properly account for the MEPS survey design when making estimates for this small subgroup, we extracted records from all respondents and constructed a flag to identify which respondents were in the analytic sample. Although only persons with an ICD-9 code of 295 made up our study sample, all observations were kept in the analytic file to maintain the survey structure and create the appropriate standard errors ( 6 ). In accordance with MEPS guidelines for pooling years of data, we factored the weights by five, the number of years in our data set ( 7 ). With this adjustment to the sampling weights, the estimates of totals (and their standard errors) and proportions reflect the new multiyear period.

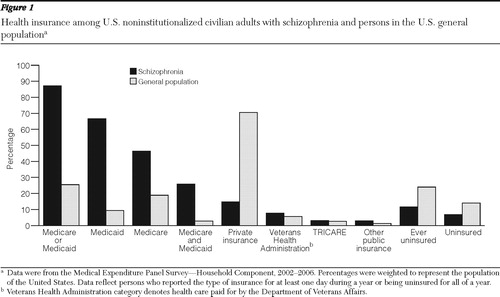

The primary variable of interest was type of health insurance coverage. This was examined in two ways. First, we displayed proportions with various types of health insurance using summary variables that indicated whether the person reported health insurance coverage for at least one day during the year. We then created an indicator to capture persons who received care from the Veterans Health Administration if the VA paid any amount during the year. These variables were not mutually exclusive, so comparisons along person characteristics could not be performed. We also present categories of health insurance for the MEPS general population as a point of reference.

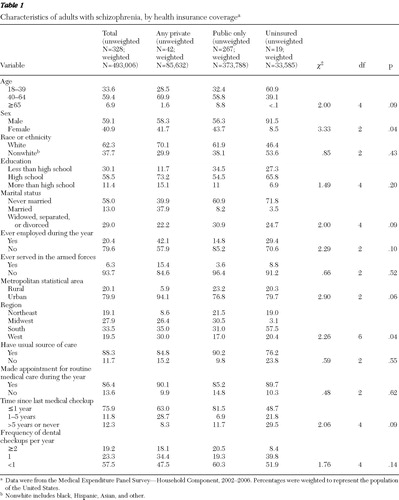

Second, a summary insurance coverage indicator consisting of the mutually exclusive categories of any private insurance any time during the year, only public insurance, and uninsured all of the year was used to compare sociodemographic and access-to-care variables by insurance type. The private category consisted of general private insurance, TRICARE, employer or union group, self-employed, nongroup coverage, other group coverage, coverage through an unknown private category, and coverage from a policyholder living outside the reporting unit. The public category included Medicare, Medicaid, and other public hospital or physician coverage.

Nationally weighted proportions of health insurance coverage for persons with schizophrenia and for the U.S. general population were estimated. We also determined whether type of health insurance was related to differences in demographic characteristics and access to care in this population with chi square tests. SAS-Callable SUDAAN was used for all analyses to account for the complex sampling design of the MEPS.

The study protocol was reviewed by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, which deemed this study exempt because data were publicly available and deidentified.

Results

The analytic sample contained 328 records representing 493,006 U.S. noninstitutionalized, civilian adults per year with schizophrenia. Sixty-seven percent reported they had Medicaid, 46% had Medicare, 87% had either Medicaid or Medicare, 26% had both Medicaid and Medicare, 8% received care from the Veterans Health Administration, 6% had other public insurance or TRICARE, and 15% reported having private insurance for at least one day during a given year ( Figure 1 ). About 7% were uninsured all of the year. In the U.S. general population, the analytic sample included 117,532 records representing 220,280,457 adults per year. Twenty-six percent of the general population reported having Medicare or Medicaid, 71% reported having private insurance, and 14% reported being uninsured throughout the year.

Type of insurance coverage was examined across demographic and access-to-care variables among persons with schizophrenia. Persons with schizophrenia who were uninsured tended to be male (92%), nonwhite (54%), and unmarried (97%) ( Table 1 ). Those with private insurance had a higher employment rate (42%) than those with public insurance (15%) or the uninsured (29%). Access to care also tended to be reduced among persons without insurance in terms of having a usual source of care and time since last medical checkup. Thirty percent of persons who were uninsured reported that more than five years had elapsed since their last medical checkup, about three times the rate of those with health insurance.

|

Discussion

This study investigated the rates and types of health insurance coverage among adults in a civilian, noninstitutionalized U.S. population-based sample who reported having schizophrenia. We documented the high prevalence of public insurance among those with schizophrenia, with almost 90% having either Medicare or Medicaid. Although there was a lower rate of uninsurance (7%) compared with the general population (14%), almost all persons with schizophrenia should be eligible for public insurance.

Uninsured persons with schizophrenia tended to be men who had never married or who were widowed, separated, or divorced, representing a population of persons with a serious illness who are likely to be socially isolated. Lack of insurance was marginally associated with not having a recent medical checkup (p=.09). Because recent medical checkups are associated with higher completion of prevention recommendations, lack of insurance may affect medical outcomes for this group.

A previous study by Yanos and colleagues ( 8 ) examined the association of insurance status with demographic characteristics and service use in a group of 539 persons with schizophrenia spectrum disorders from a statewide behavioral health care system ( 8 ). The investigators found a 20% rate of unisurance, which was substantially higher than our findings. They also found that uninsurance was associated with younger age, Latino ethnicity, and male sex. However, the sample in Yanos and colleagues' study was not a household survey; rather it captured those who had presented for services, so it included people who may have been homeless or institutionalized and who may be more likely to be uninsured.

Stable and comprehensive health insurance coverage is particularly important for persons with schizophrenia, because they require long-term health services to treat this chronic illness. In addition to improving the quality of life in schizophrenia, effective treatment reduces the burden to caregivers, reduces health care costs, and improves overall physical health ( 9 ). In contrast, persons with schizophrenia who do not take antipsychotic medications as recommended have increased hospitalizations, use of emergency psychiatric services, violence, victimization, and substance abuse and reduced mental functioning, all of which increase costs ( 10 ). Health insurance for persons with schizophrenia also pays for ongoing psychotherapy and engagement in rehabilitation or assertive community treatment programs, which are recommended by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) guidelines ( 11 ). A recent examination of Florida Medicaid claims records from 1996 to 2001 for persons with schizophrenia found that only 18% of acute treatment and 7% of maintenance treatment met all PORT quality standards ( 12 ). The investigators found that although there was a greater likelihood of receiving an antipsychotic over time, there was also a lower likelihood of mental health visit continuity.

There were several limitations regarding our sample of persons with schizophrenia. Although it is a population-based survey weighted to the national population, the MEPS is not intended to estimate prevalence of medical conditions; rather it is designed to provide estimates of insurance and health service access and utilization ( 13 ). Although the estimated prevalence of schizophrenia is between .5% and 1.1%, the MEPS estimate was lower ( 14 ). Because it is a household survey, it likely does not capture persons with schizophrenia living in supported arrangements, such as group homes, or institutional settings, such as prisons. It may also underrepresent undocumented immigrants and persons who are homeless, groups that are more likely to be uninsured ( 15 ). It is also possible that schizophrenia was underreported because one respondent provides information for the entire household and the medical condition enumeration comes from an open-ended question. In addition, persons with schizophrenia who do not go to a medical provider would not have that data imputed. Finally, even after several years of MEPS data were combined, the sample of persons with schizophrenia may have been too small to detect significant differences between health insurance type and demographic variables and access to care.

Conclusions

We used a national survey to estimate health insurance coverage among noninstitutionalized adults with schizophrenia. Almost all U.S. adults with schizophrenia are eligible for government health insurance, but a nonnegligible minority were uninsured. This is an especially vulnerable population because they not only have an increased risk of many physical diseases, but they also are in need of lifelong psychiatric care. These health insurance estimates highlight opportunities for improving health service delivery for this vulnerable population, particularly because almost all of those with health insurance were covered by government administered programs. However, the high proportion of persons with schizophrenia covered by public insurance programs suggests that future provision of universal coverage for this diagnostic group would not have a strong effect on overall costs. Future directions for research may include determining the risk factors for uninsurance among persons with schizophrenia and finding opportunities for improving care for the vast majority who are receiving public insurance.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by the Psychiatric Epidemiology Training Program and through grant 5-T32-MH014592 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al: The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:1122–1129, 2005Google Scholar

2. Compton MT, Weiss PS, Phillips VL, et al: Determinants of health plan membership among patients in routine US psychiatric practice. Community Mental Health Journal 42:197–204, 2006Google Scholar

3. Zeber JE, Grazier KL, Valenstein M, et al: Effect of a medication copayment increase in veterans with schizophrenia. American Journal of Managed Care 13:335–346, 2007Google Scholar

4. Yanos PT, Crystal S, Kumar R, et al: Characteristics and service use patterns of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 52:1644–1650, 2001Google Scholar

5. Ezzati-Rice TM, Frederick Rohde F, Janet Greenblatt J: Methodology Report #22: Sample Design of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component, 1998–2007. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008. Available at meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb////data_files/publications/mr22/mr22.pdf Google Scholar

6. Machlin S, Yu W, Zodet M: Computing Standard Errors for MEPS Estimates. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005. Available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/survey_comp/standard_errors.jsp Google Scholar

7. MEPS HC-036: 1996–2007 Pooled Estimation File. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2009. Available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h36/h36u07doc.shtml Google Scholar

8. Yanos PT, Lu W, Minsky S, et al: Correlates of health insurance among persons with schizophrenia in a statewide behavioral health care system. Psychiatric Services 55:79–82, 2004Google Scholar

9. Tandon R, Targum SD, Nasrallah HA, et al: Strategies for maximizing clinical effectiveness in the treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 12:348–363, 2006Google Scholar

10. Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al: Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:453–460, 2006Google Scholar

11. Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–217, 2004Google Scholar

12. Busch AB, Lehman AF, Goldman H, et al: Changes over time and disparities in schizophrenia treatment quality. Medical Care 47:199–207, 2009Google Scholar

13. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: Survey Overview. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007. Available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/workbook/WB-Survey_Overview.pdf Google Scholar

14. Eaton WW, Martins SS, Nestadt G, et al: The burden of mental disorders. Epidemiologic Reviews 30:1–14, 2008Google Scholar

15. Ku L: Health insurance coverage and medical expenditures of immigrants and native-born citizens in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 99:1322–1328, 2009Google Scholar