Application of a Firearm Seizure Law Aimed at Dangerous Persons: Outcomes From the First Two Years

In August 2004 Indianapolis police officers responded to a call about a man firing a rifle and were met by a fusillade of bullets from an assault rifle that killed one officer and wounded four others before the shooter was killed by police ( 1 ). Police learned that nine firearms and over 200 rounds of ammunition had been confiscated from the shooter eight months earlier. At that time, police said he was delusional and dangerous and took him to a local hospital, where he was admitted and diagnosed as having paranoid schizophrenia; he was not civilly committed ( 2 ). After his release, the shooter sought the return of his weapons, and despite strong police misgivings, they were returned in March 2004 ( 3 ).

After this tragedy state legislators focused on finding a way to prevent persons with mental illness from gaining access to firearms ( 4 ). The Indiana Commission on Mental Health, already in session, appointed a work group to study this issue ( 5 ), which recommended in early October that the commission propose "legislation that would balance the interest of the public (authorizing the police to seize firearms/weapons from the mentally ill)" with the interest of a person's right to own a firearm ( 6 ). In late October 2004 the commission unanimously approved draft legislation to permit "a law enforcement officer to seize a firearm possessed by an individual whom the officer reasonably believes to be mentally ill and dangerous" ( 7 ).

In January 2005 this bill was introduced in the Indiana legislature as an amendment of the civil commitment statute ( 8 ). The bill was subsequently approved by the House and the Senate after significant amendments. The bill sent to the governor amended Indiana's criminal code; it defined a dangerous person as one who presents an imminent present risk or possible future risk of injury to self or others and who has not consistently taken medication to control "a mental illness that may be controlled by medication" or who has a history to support "a reasonable belief that the person has a propensity for violent or emotionally unstable conduct" ( 9 ). The bill used a very broad preexisting statutory definition of mental illness ( 10 ). An officer could seize a weapon from a dangerous person without a warrant, but he or she was required to submit a written statement to the appropriate court describing the reasons for believing the person was dangerous. The court was required to hold an initial hearing on the firearm seizure within 14 days, and the state had to prove its case for retention by clear and convincing evidence. If this burden of proof was met, the court could order the retention of the weapon by the police and was obliged to suspend the person's license to carry a firearm. If the gun owner did not regain custody of the weapons within five years, the weapons could be ordered destroyed by the court ( 9 ). The bill was signed into law in May 2005 and became effective on July 1, 2005 ( 11 ).

Indiana thus entered the national discussion about the perceived link between mental illness and violence and the debate about whether persons with mental illness should have access to firearms. Indiana became the second state to pass a law specifically authorizing the seizure of firearms from persons with mental illness. Connecticut passed a similar, but narrower, law in 1999, also after a shooting tragedy ( 12 ). The issue of confiscation of legally owned weapons from U.S. citizens is controversial. The second amendment to the Constitution—which reads "A well regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed"—was recently interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court to ensure the right of individuals to own firearms. The majority opinion acknowledged that some gun control provisions were reasonable, noting that "nothing in our opinion should be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons or the mentally ill" ( 13 ).

The legal prohibition of gun ownership by persons with mental illness is a relatively recent phenomenon. Simpson, in a 2007 review ( 14 ), noted that the first federal statute to prohibit gun ownership by persons with mental illness was the Gun Control Act of 1968 ( 15 ), which permanently prohibited persons "adjudicated as a mental defective" or who had been "committed to any mental institution" from purchasing a firearm from a federally licensed firearm dealer. The Firearm Owner's Protection Act of 1986 ( 16 ) provided a means to regain the right to own a firearm and restated that persons who had been committed to a mental institution could not own a firearm. The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act ( 17 ), passed in 1993, required use of the National Instant Criminal Background Check (NICS) by all federally licensed firearms dealers before selling a firearm to an individual. However, state participation in sending data to NICS was voluntary; only 22 states had contributed mental health data by 2007, for a total of 167,903 records, most from Virginia (81,233 records, 48%) and Michigan (73,382 records, 44%). Fifteen states contributed fewer than 100 records each ( 18 ), and Indiana was not a participating state. The Brady Act was amended in the wake of the Virginia Tech shootings by the NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 ( 19 ), which provided financial incentives to the states to contribute mental health records to the NICS database and financial penalties if they did not. States may place a person in the denied persons file of the NICS Index without disclosing that the disqualification was due to a mental health issue. NICS does not request or hold any medical records or any details of an individual's mental health history ( 18 ).

Simpson's review ( 14 ) of state statutes on gun ownership by persons with mental illness found that four states had no laws on this issue, 12 states prohibited persons with mental illness from obtaining a permit to carry a concealed weapon, and 34 states had varying prohibitions on gun ownership by persons with mental illness. In states with bans on ownership, at a minimum, persons who had been involuntarily hospitalized or found incompetent could not buy, receive, or own a firearm. The duration of the bar on ownership varied from state to state, as did the possibility of restoration of the right to own a firearm. In Indiana a license is required to carry a handgun but no license is needed to possess a firearm; also, it is unlawful in Indiana to sell a firearm to someone who is "mentally incompetent" ( 20 ).

Connecticut was the first state to allow police to legally seize firearms from citizens on the basis of the presence of "risk of imminent personal injury to self or others" ( 21 ). Police in that state must file an affidavit and obtain a warrant before seizure, and a court hearing must be held within 14 days of the seizure, at which time the judge decides whether the police may retain the weapons for one year. As of 2008 the Connecticut law had been used 222 times over the course of nearly nine years, leading to the seizure of 1,713 weapons ( 22 ).

The study presented here was undertaken to examine the use of Indiana's statute in Marion County, which shares the same boundaries as the city of Indianapolis. Marion County police and prosecutors began to use the 2005 gun seizure law shortly after its effective date of July 1, 2005. This article describes the demographic characteristics of the persons in possession of the weapons at the time of confiscation and the circumstances of all of the firearm seizure cases heard in the Marion County court system in calendar 2006 and 2007 and describes the changes in the use of the seizure law over those two years.

Methods

All cases filed in Marion County under the gun seizure law were heard by one judge in her misdemeanor and minor felony criminal court. With the assistance of court personnel, all firearm seizure cases that had a final hearing in 2006 and 2007 were identified. Using a standardized data collection form, demographic information was recorded about the individual from whom the firearm was seized. Several cases were initiated based on incidents that occurred before the effective date of the law; in these cases, a seizure date of July 1, 2005, was used for the purpose of calculating the time to the hearing date. The officer's written statement was used to determine the circumstances of the seizure, using one or more of the following categories: risk of suicide, risk of violence, domestic disturbance, intoxication on alcohol or drugs, active psychosis, and other. The officer's written statement was also used to determine the resolution of the situation, using one or more of the following categories: immediate detention (involuntary transport for psychiatric evaluation), arrest, voluntary transport to the hospital, no police action, and other.

The outcome of the court hearing was drawn from the court order or the clerk's notation in the file as to the judge's decision, using the following categories: firearms to be retained based on clear and convincing evidence, firearms to be retained with the consent of owner, firearms to be returned to owner, failure of owner to appear for the hearing, inability to serve owner with notification of hearing, and license suspended.

The data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and were analyzed with GraphPad online software to determine the t test or Fisher's exact test; p<.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance.

This study was granted exempt status in February 2007 by the Institutional Review Board of Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

Results

The court held final firearm retention hearings for 55 cases in 2006 and 78 cases in 2007. The defendants were predominantly white (N=111, 83%), male (N=107, 81%) and middle aged (mean±SD=42.1±14.0); the percentage of black defendants (N=22, 17%) was less than that for Indianapolis overall (26%). The mean number of firearms seized per incident was 3.0±4.4 (range, 1–25) in 2006 and 2.5±3.2 (range, 1–18) in 2007. In 2006, 26 (47%) of the defendants had a prior arrest record in Marion County, and 18 (23%) had such a record in 2007 (p=.005), but only a minority of these had a prior conviction (N=11, 42%, in 2006; N=7, 39%, in 2007). Of these, in each year, only two persons had a prior conviction for a violent offense (battery, resisting arrest, and pointing a firearm). Most of the prior arrests were drug related (N=18, 69%, in 2006; N=9, 50%, in 2007). Among the prior arrests for crimes against a person (N=10, 38%, in 2006; N=8, 44%, in 2007), only one of the offenses appeared serious (aggravated assault).

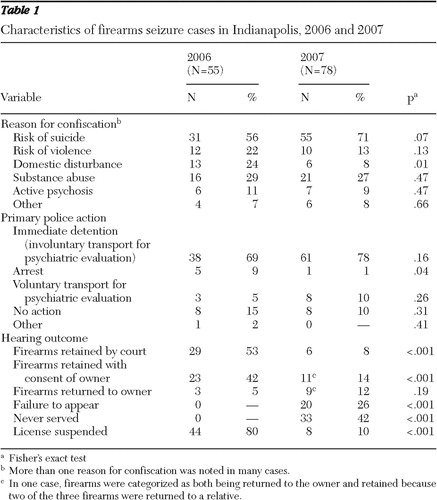

As shown in Table 1 , the most common reasons for firearm seizure were risk of suicide, substance abuse, risk of violence, domestic disturbance, and psychosis, in that order. The pattern of seizure circumstances changed over the two years of the study. The frequency of firearm seizure because of domestic disturbance significantly declined between 2006 and 2007 (from 24% to 8%; p=.01). Over the same period, the frequency of seizure because of risk of suicide increased (from 56% to 71%) and the frequency of seizure because of risk of violence declined (from 22% to 13%), although these changes were not significant. It should be noted that all of the cases of risk of violence were a result of threats or fear of violence and not actual violence. The prevalence of substance abuse and psychosis as reasons for confiscation was stable.

|

A large majority of the individuals from whom firearms were confiscated were immediately detained at the time of confiscation; the frequency of this outcome increased over the study, from 69% to 78%. Police took no action in 15% of the cases in 2006 and 10% of the cases in 2007. In 2006, 9% of the cases resulted in an arrest, but only 1% of the cases led to an arrest in 2007 (p=.04). A few individuals were voluntarily transported to the hospital (5% in 2006 and 10% in 2007).

In 2006 final hearings took place an average of 174±110 days after the date of the seizure, but in 2007 the hearings occurred significantly later (323±158 days) (t=2.88, df=131, p=.005). The court came to a clear determination of the fate of the confiscated weapons in every case heard in 2006: in 53% of the cases, the court retained the weapons based on clear and convincing evidence; in nearly all of the remaining cases (42%), the gun owners voluntarily gave up their weapons. Only in 6% of the cases were the guns returned to their owners. In accordance with the statute, which required suspension of the person's license to carry a firearm after a finding of dangerousness (10), in 80% of cases the owner either agreed to surrender his or her license (N=15, 27%) or lost it by court order (N=29, 53%).

The pattern of hearing outcomes changed significantly in 2007 ( Table 1 ). Retention of firearms by decision of the court dropped to only 8% of cases, and only 14% of cases were resolved by voluntary surrender of the weapons. Instead, in more than two-thirds of the cases, the individual either could not be found for service of notification of the court hearing (42%) or did not appear in court (26%). In these cases, the court ordered the police to retain the weapons for five years and set the cases for rehearing at that time. Overall, the court deferred final judgment in two-thirds of the cases heard in 2007 but ordered the police to retain the weapons, in contrast to 2006 when all of the cases heard were resolved. Finally, in 2007 only eight cases (10%) resulted in suspension of the license to own a firearm: six by court order and two by agreement.

Further analysis of the database revealed no significant differences between white persons and black persons who had guns seized, except whites were more likely than blacks to have substance abuse listed as a reason for confiscation (N=35 of 111, 32%, versus N=2 of 22, 9%) (p=.04). No significant differences were found between the men and women who had firearms confiscated from them. Finally, the reasons for confiscation did not differ significantly among those with and without prior arrest records.

Discussion

Marion County's use of Indiana's firearm seizure law showed significant changes over the course of the first two calendar years of its implementation. Based on the number of cases resolved in court, the law was used 55 times in 2006 and 78 times in 2007. To put this in context, the overall rate of use of the firearm seizure law in 2006 and 2007 in Indianapolis, a city of 781,000 persons in 2000, was 8.5 cases per year per 100,000 residents, which far exceeded the rate in Connecticut (.43 cases per year per 100,000), the only other state with such a law ( 22 ), even when factoring in the relative prevalence of gun ownership in Indiana (39.1%) versus Connecticut (16.7%) ( 23 ).

The pattern of the reasons for gun seizure changed over the first two years of the law's use in Indianapolis—that is, the number of confiscations because of risk of suicide increased (p=.07) while the number of confiscations because of risk of violence or in the context of a domestic disturbance decreased (p<.01). The reasons for these changes could not be discerned from the police reports on the incidents. The number of seizures in the context of domestic disturbances over the two years was an unexpected finding. Although domestic violence is a major issue for society and often presents police officers with challenging situations, this scenario was not among the reasons for firearm confiscation envisioned by the authors of the firearm seizure legislation. The proportion of firearm seizures related to active psychosis was steady over the two-year study period and was one of the least frequent reasons for confiscation, even though the tragic shooting that led to the passage of the firearm seizure law was most likely a result of paranoid psychosis.

The pattern of disposition of the firearm seizure cases also changed over the two-year study period. In 2006 cases took nearly 180 days to go to a final hearing, but in 2007 hearings took place an average of almost one year after the confiscation. This significant change can be accounted for, in large part, by the number of cases that were resolved without the presence of the gun owner; in 53 cases in 2007 the owner either could not be found to be served with notice of the hearing or did not appear after having been served. In contrast, all of the 55 cases in 2006 were decided based on a hearing in which the defendant was present.

In 2006, 95% of the cases resulted in retention of the weapons, either by court order or by voluntary surrender. In 2007, of the 26 cases that went to a formal hearing, only 65% resulted in retention and the weapons were returned in 35%. However, in 2007 the court also began to clear a backlog of unheard cases by issuing five-year retention and review orders in cases where the defendant either did not show up for scheduled court hearings or could not be located for service of notice of the court hearings; the court resolved nearly as many cases in this manner in 2007 (N=53) as it did by formal hearing in 2006 (N=55). Thus, despite the decline in the number of cases formally adjudicated and an increase in the number of cases where firearms were returned to the gun owner, the net effect of the court's strategy for disposing of backlogged cases was to continue to retain weapons seized by the police from dangerous persons at a fairly constant rate over the two-year study period.

Conclusions

Indianapolis' experience with the introduction and implementation of a firearm seizure law, which had its origins in the political response to a police shooting death at the hands of a person with very probable psychosis, showed that active symptoms of psychosis were rarely a cause for confiscation. Instead, risk of suicide and risk of substance abuse were the predominant reasons for gun seizure. In addition, the implementation of the law in the court proved as important as its use in the community. Although formal hearings increasingly led to return of weapons over the study period, retention for failure to appear or inability to locate the defendant assumed a major role in the second year of the bill's implementation. Although the seizure law has been a useful tool for police in decreasing the risk of firearm use in volatile situations, its overall impact must be considered minimal, because only 360 weapons were seized in two years in a city of more than 780,000 persons, nearly 40% of whom own a firearm.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The author thanks Judge Barbara Collins and court reporter Linda Broadus, of the Marion Superior Court, Criminal Division 8, for facilitating access to the court records of the firearm seizure cases and Benjamin May, M.D., for data collection for the 2006 cases.

The author reports no competing interests.

1. Spalding T, Ryckaert V: IPD officer fatally shot. Indianapolis Star, Aug 18, 2004. www2.indystar.com/articles/4/171264-1254-228.html Google Scholar

2. Kim T, Kelly F: A neighborhood mystery: "everyone around here thought he was sick." Indianapolis Star, Aug 19, 2004. Available at www2.indystar.com/articles/7/171569-5557-228.html Google Scholar

3. Strauss J, Spalding T, Ryckaert V: Gunfire spurred a flurry of 911 calls: IPD confiscated, then returned guns to shooter. Indianapolis Star, Aug 19, 2004. Available at www2.indystar.com/articles/0/171577-6940-228.html Google Scholar

4. Schneider MB, Solida MM, Strauss J: Assault-gun ban unlikely: survey of state lawmakers shows many wary of limits on weapons. Indianapolis Star, Aug 22, 2004. Available at www2.indystar.com/articles/7/172435-4847-P.html Google Scholar

5. Minutes of the September 21, 2004, Meeting of the Indiana Commission on Mental Health. Indianapolis, Ind, 2004. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/interim/committee/2004/committees/minutes/COMH7AL.pdf Google Scholar

6. Culver RD: Memo to the Members of the Indiana Commission on Mental Health Regarding the Report of the Indiana Commission on Mental Health Work Group on the Seizure of Firearms/Weapons From the Mentally Ill. Oct 7, 2004. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/interim/committee/2004/committees/minutes/MRDD79T.pdf Google Scholar

7. Minutes of the October 28, 2004, Meeting of the Indiana Commission on Mental Health. Indianapolis, Ind, 2004. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/interim/committee/2004/committees/minutes/COMH7AS.pdf Google Scholar

8. House Bill No 1776, Introduced Version. Indiana Legislature, 2005 Regular Session. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/bills/2005/IN/IN1776.1.html Google Scholar

9. House Enrolled Act No 1776. Indiana Legislature, 2005 Regular Session. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/bills/2005/HE/HE1776.1.html Google Scholar

10. Indiana Code, Title 12, Article 7, Chapter 2, Section 130 (IC 12-7-2-130), Mental Illness. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/ic/code/title12/ar7/ch2.html Google Scholar

11. Indiana Code, Title 35, Article 47, Chapter 14 (IC 35-47-14), Proceedings for the Seizure and Retention of a Firearm. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/ic/code/title35/ar47/ch14.html Google Scholar

12. Buckley F: Connecticut allowing police to seize firearms from potential criminals. Atlanta, Ga, Cable News Network, Jul 2, 1999. Available at www.cnn.com/US/9907/02/gun.seizures Google Scholar

13. District of Columbia v Heller, 554 US (2008). Available at www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/07-290.ZO.html Google Scholar

14. Simpson JR: Bad risk? An overview of laws prohibiting possession of firearms by individuals with a history of mental illness. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 35:330–338, 2007Google Scholar

15. Public Law No 90-618, 82 Stat 1213Google Scholar

16. Public Law No 99-308, 100 Stat 449Google Scholar

17. Public Law No 103-159, 107Stat1536Google Scholar

18. Statement of Rachel Brand, Assistant Attorney General for Legal Policy, Department of Justice, Before the Subcommittee on Domestic Policy, Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Washington, DC, US House of Representatives, May 10, 2007. Available at www.usdoj.gov/archive/opa/mediashield/rlb-testimony061407.pdf Google Scholar

19. Public Law No 110-180, 121 Stat 2559Google Scholar

20. Indiana Code, Title 35, Article 47, Chapter 2 (IC 35-47-2), Regulation of Handguns. Available at www.in.gov/legislative/ic/code/title35/ar47/ch2.html Google Scholar

21. General Statutes of Connecticut, Title 29, Chapter 529, Section 29-38cGoogle Scholar

22. Rose V, Reilly M: Gun Seizure Law: OLR Research Report 2008-R-0280. Hartford, Conn, State of Connecticut General Assembly, Jun 25, 2008. Available at www.cga.ct.gov/2008/rpt/2008-R-0280.htm Google Scholar

23. BRFSS Survey Results for 2001: Nationwide Firearms. Raleigh, North Carolina State Center for Health Statistics. Available at www.schs.state.nc.us/SCHS/brfss/2001/us/firearm3.html Google Scholar