Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Use of Psychotherapy: Evidence From U.S. National Survey Data

The U.S. Surgeon General's 1999 report on mental health concluded that persons from racial and ethnic minority groups have less access to and are significantly undertreated in mental health services ( 1 ). Studies have shown that among adults with a diagnosed mental disorder, only 22.4% of Latinos and 25.0% of African Americans received any treatment, compared with 37.5% of Caucasians ( 2 ). People from racial-ethnic minority groups are more likely than Caucasians to delay or never seek mental health treatment, even after adjustment for their socioeconomic status ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ).

Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and the combination of these two are the major effective treatments for depression and anxiety ( 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). Racial and ethnic disparities in pharmacotherapy use have been examined extensively in the literature ( 3 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ). Mallinger and colleagues ( 11 ) found that Caucasians are six times more likely than African Americans to use second-generation antipsychotics. Chen and Rizzo ( 15 ) reported that Latinos and African Americans are significantly less likely than Caucasians to take antidepressants. Empirical evidence also shows that treatment preferences differ according to race and ethnicity ( 16 , 17 , 18 ). For example, Givens and colleagues ( 16 ) found significant ethnic differences in medication use for depression. Persons from ethnic minority groups are more likely to believe that antidepressants are addictive, and they are more likely to use prayer and counseling for their depression treatment ( 18 ).

There is no direct evidence, however, of racial and ethnic differences in expenditure on and use of psychotherapy. Some studies examined sociodemographic characteristics associated with psychotherapy use, but they did not include racial and ethnic effects ( 19 , 20 , 21 ). To bridge this gap in the literature, this study used a nationally representative sample from 1996 to 2006 to examine racial and ethnic disparities in expenditure on and use of psychotherapy.

Methods

Data and variables

We used data from the 1996–2006 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) conducted by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ( 22 ). The MEPS database consists of a number of files. The Consolidated File is a person-year-level database, which provides detailed consumer demographic characteristics, socioeconomic characteristics, health status, and health insurance information. The Office-Based Medical Provider Visit file provides detailed types of treatment received during each physician visit, such as psychotherapy and counseling, and types of expenditure (such as out-of-pocket payment and total expenditure) associated with each visit. Patients' medical conditions are also available in the form of ICD-9 codes. Merging these two files enabled us to link patients' demographic and socioeconomic characfor teristics with health care expenditure for and use of psychotherapy by patients with depression and anxiety disorders. (Because we used a public data set that does not identify individuals, institutional review board approval was waived.)

We used a two-part model to examine psychotherapy expenditure and use ( 23 ). Specifically, we constructed binary variables indicating whether the patient had any psychotherapy or counseling during the survey year. If patients had used either, we examined total expenditures for the service. We also calculated the ratio of average out-of-pocket payment to the total expenditures for each visit. These outcomes provided information on racial and ethnic disparities in terms of the likelihood of accessing psychotherapy or counseling, total expenditures for the service, and the patients' cost burden. All expenditures were adjusted to constant 2006 dollars with the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

Variables associated with health care utilization have been categorized as predisposing, need-related, and enabling factors ( 24 ). Predisposing variables included age, gender, marital status, and education. Interview language (a binary variable: 1 if the interview was conducted in English and 0 otherwise) was also included in this category. Need-related factors included in this study were self-reported general health status, self-reported mental health status, and limitations in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. We also included a binary variable indicating whether the patient had depression or an anxiety disorder.

Enabling factors included family income, health care access (whether the patient had a usual source of care), health insurance, metropolitan statistical area, and U.S. census region. We categorized health coverage as uninsured, Medicaid, Medicare, or other public health plan and private health plans. We also included year indicators to capture intertemporal effects on expenditure and use.

We compared racial and ethnic disparities between Caucasian non-Latinos (Caucasians) and Latinos (Latinos) and between Caucasian non-Latinos (Caucasians) and African-American non-Latinos (African Americans). Persons of other races, as well as patients who identified themselves as being of multiple races, were excluded. Thus we had a sample of 7,851 adults at least 18 years of age and who had sought treatment for depression or anxiety in an office visit in a year in which each survey was conducted. After we excluded 475 observations where information on our study variables was missing, our final sample included 5,592 Caucasians, 1,125 Latinos, and 659 African Americans.

Analysis

We performed bivariate and multivariable analyses. Chi square tests were used to test for significant differences among categorical variables, and t tests were used for continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regressions were used to examine the probability of using any psychotherapy or counseling, and odds ratios were reported. Ordinary least-squares regressions were used to examine total expenditure and average out-of-pocket-payment shares among persons using any psychotherapy. We took the natural logarithms of total expenditure to adjust for its skewed distribution ( 25 ). All regressions were adjusted for sampling weights provided in MEPS to ensure that the results were nationally representative of the noninstitutionalized civilian U.S. population.

We then used Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition techniques ( 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ) to determine the extent to which utilization and expenditure disparities reflected differences in observable population characteristics and to identify the most important factors associated with these disparities. The Blinder-Oaxaca approach is a regression-based method. For example, to decompose the disparities of average out-of-pocket-payment shares between Caucasians and Latinos, we estimated multivariable regressions for these two groups separately. We then subtracted these two estimated equations and decomposed these differences into two parts: differences resulting from all of the observed population characteristics (that is, all of the control variables) and differences because of unobserved heterogeneities associated with race and ethnicity, such as cultural background and beliefs ( 15 , 30 ). We repeated this procedure to examine racial disparities for African Americans and for the other study outcomes.

Results

Bivariate analysis

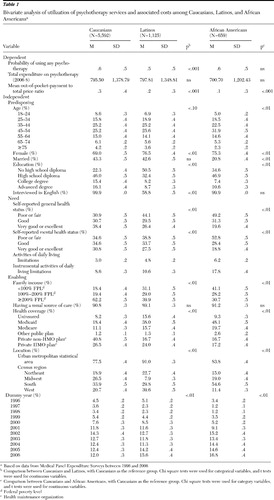

Table 1 summarizes the sample statistics for utilization and expenditures for any psychotherapy and sample characteristics by race-ethnicity for the pooled 1996–2006 sample. Caucasians were significantly more likely than Latinos (p<.001) but not significantly more likely than African Americans to have had any psychotherapy. Conditional on use of any psychotherapy, total expenditures did not differ significantly by race or ethnicity. Caucasians, however, shared 29% of the total cost, compared with only 19% for Latinos (p<.001) and 14% for African Americans (p<.001).

|

Compared with Caucasians, Latinos and African Americans were more likely to be uninsured. They also were more likely than Caucasians to have public health insurance. Approximately 48% of African Americans and 38% of Latinos were enrolled in Medicaid, compared with just 18% of Caucasians. In contrast 34% of African Americans and 41% of Latinos were enrolled in private health insurance, compared with 67% of Caucasians.

Latinos and African Americans were more likely than Caucasians to report worse mental health status (53% of African Americans and 39% of Latinos versus 35% of Caucasians reported poor or fair mental health) and general health status (49% of African Americans and 44% of Latinos versus 31% of Caucasians reported poor or fair general health).

Multivariable regressions

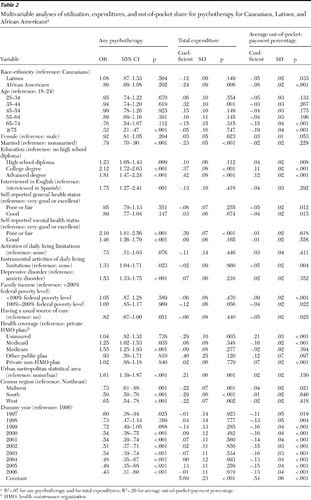

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariable models.

|

Utilization. Utilization no longer varied by race and ethnicity in the multivariable analysis. English-speaking patients were 75% (p=.001) more likely than non-English-speaking patients to receive any psychotherapy or counseling. People who reported being in poor or fair mental health were more than twice as likely to use any psychotherapy as those reporting very good or excellent mental health. Compared with people enrolled in private health maintenance organization (HMO) plans, individuals covered by Medicare were 55% (p<.001) more likely to have had psychotherapy. There were no significant differences in utilization between uninsured persons and those enrolled in private HMO health plans. Having a usual source of care did not affect the probability of receiving psychotherapy. The year indicators demonstrated that in later years participants were less likely to use psychotherapy.

Total expenditure and share of out-of-pocket payment. African Americans had significantly lower total expenditures on psychotherapy than did Caucasians (coefficient=-.24, p<.01). Latinos and African Americans also had significantly lower out-of-pocket-payment shares compared with Caucasians (Latinos, coefficient=-.05, p<.05; African Americans, coefficient=-.08, p<.001). Compared with persons enrolled in private HMO plans, uninsured individuals (coefficient=.21, p<.001) and persons with private non-HMO plans (coefficient=.07, p<.001) had higher out-of-pocket-payment shares, whereas persons enrolled in Medicaid (coefficient=-.16, p<.001) had significantly lower out-of-pocket-payment shares. The results by year showed that out-of-pocket-payment shares for psychotherapy were lower from 1997 onward compared with 1996.

Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition

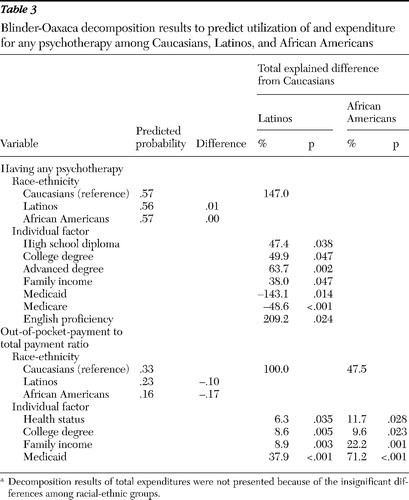

The decomposition results are provided in Table 3 . The most important factor affecting differences in the probability of receiving any psychotherapy or counseling between Caucasians and Latinos was English proficiency. The results suggest that if there were no language barriers, Latinos would be twice as likely as Caucasians to use psychotherapy services. Our results also revealed that Medicaid and Medicare are two major factors that limit racial and ethnic disparities in psychotherapy use. In other words, if fewer Latinos had Medicaid and Medicare coverage, they would be far less likely to use psychotherapy and the disparities would increase significantly.

|

Both observed population characteristics and unobserved heterogeneity were important in explaining racial-ethnic disparities in the out-of-pocket-payment shares for psychotherapy. Observed population characteristics explained almost all of the disparities between Caucasians and Latinos and 47.5% of these disparities between Caucasians and African Americans, respectively ( Table 3 ). Medicaid coverage was by far the most important factor associated with out-of-pocket-payment disparities, accounting for 37.9% of observed differences for Latinos and 71.2% of observed differences for African Americans. Family income explained 8.9% and 22.2% of the observed differences for Latinos and African Americans, respectively, followed by education and health status.

The importance of language barriers. These results highlight the key role of language barriers for obtaining psychotherapy treatment. People with English language barriers were approximately 24% less likely to receive any psychotherapy. In the Latino cohort, just 59% were interviewed in English, compared with nearly 100% of Caucasians and African Americans. When we further divided Latinos into two groups—those interviewed in English and those not—we found no significant differences in utilization between Caucasians (N=5,592) and Latinos who spoke English (N=661, mean±SD probability=.57±.50 versus .58±.49, respectively), but Latinos who were interviewed in Spanish (N=464, mean±SD probability=.43±.50) were 14% less likely than Caucasians to use psychotherapy (p<.001), and this effect remained significant even after we controlled for other covariates. (The full set of regression results was omitted in the interest of brevity but is available from the authors on request.) This pattern was consistent with our decomposition results above, which showed that the most important factor associated with utilization disparities was limited English proficiency.

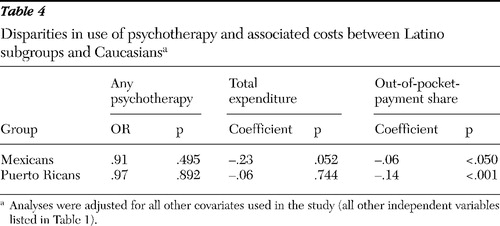

Heterogeneity among Latinos. There is substantial heterogeneity among Latino subgroups in terms of economic status, beliefs about health care use, and other factors. Such heterogeneity could lead to differences in psychotherapy use by different Latino subgroups. To investigate this issue, we reanalyzed the data for subgroups of Latinos, which included 608 Mexicans, 225 Puerto Ricans, 77 Cubans, and 215 other Latinos. Because of the sample size limitations, we reproduced our multivariable results only for Caucasians, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans ( Table 4 ). The analyses in the table controlled for all the other covariates used in the study. However, in the interest of brevity, we report results only for the race-ethnicity variables (the full set of results is available from the authors on request).

|

The Mexican and Puerto Rican indicators showed no significant effects on the probability of having any psychotherapy or on total expenditures, but they both had a significantly lower out-of-pocket-payment share compared with Caucasians. Our decomposition results (not presented) were little changed. Medicaid was again the most significant factor associated with the lower out-of-pocket-payment share for both Mexicans and Puerto Ricans. Medicaid was also the most important reason associated with the use disparities between Caucasians and Puerto Ricans, and English language proficiency was the most important factor in the disparities between Caucasians and Mexicans.

Citizenship status. Citizenship status may also affect patterns of psychotherapy use. The National Health Interview Survey, which can be linked to MEPS, has information on citizenship status for the years 1999–2006. To investigate whether including citizenship status affected the disparity results, we reestimated our models for 1999–2006 and included citizenship status. These results (available from the authors on request) were very similar to those reported here, indicating that the findings were not sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of this variable.

Discussion

Psychotherapy is one of the major treatments for depression and anxiety ( 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 ), yet there is very little evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in expenditure for its use. With a nationally representative data set from 1996 to 2006, we compared the use of, total expenditure on, and average out-of-pocket-payment shares for psychotherapy among Caucasians, Latinos, and African Americans. Previous research has found that persons from racial and ethnic minority groups were more likely to use psychotherapy than pharmacotherapy to treat depression ( 19 , 20 ). We found little evidence of racial and ethnic disparities in the propensity to use psychotherapy—a result that is consistent with previous work.

Language has been considered to be one of the most important barriers for people from racial-ethnic minority groups in accessing mental health care ( 6 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ). Proper treatment of mental disorders depends heavily on communication between physicians and their patients. This is especially true of psychotherapy, which is also known as "talk therapy" and is largely accomplished by the "exchange of verbal communications" ( 1 , 39 , 40 ). However, just 1% of U.S. psychologists are Latinos ( 41 ). Lack of bicultural and bilingual mental health providers thus makes language barriers even more significant ( 42 ).

On the other hand, language may be considered as a proxy indicator for culture. The understanding of and desired treatment for mental disorders may vary among people who speak different languages because their cultures are also different. To illustrate, Zuvekas and Fleishman ( 43 ) found that racial-ethnic differences in service use might arise in the interpretation of emotional symptoms. In some cultures, mental illness is regarded as a punishment from God or as the fault of parents ( 44 ). Magaña ( 44 ) found that individuals from Latino groups often referred in interviews to schizophrenia and other serious mental illness as "nervios" (nerves). Moreover, some individuals from minority groups may feel that admitting to having mental illness is associated with stigma, and therefore they may be less likely to seek treatment ( 34 , 36 , 37 ).

For general medical services, Caucasians usually pay lower out-of-pocket costs compared with persons from minority groups, but we found that this was not true in the case of mental health services. Latinos and African Americans had significantly lower out-of-pocket payments than Caucasians, and higher percentages of Latinos and African Americans were enrolled in Medicaid. But if there were no differences in Medicaid coverage among the racial-ethnic groups, our results indicated that Latinos and African Americans would pay substantially higher out-of-pocket costs than they pay now. Thus any reforms that might affect Medicaid coverage of mental health care would significantly affect the mental health treatment of persons in racial-ethnic minority groups.

The results also suggest that mental health coverage among private health plans should be carefully reviewed. People enrolled in public health plans were more likely to use psychotherapy and to pay less out of pocket than people with private health insurance, even after adjustment for mental health status and other covariates.

We found significant geographic variation in psychotherapy use. People who resided in urban locations were more likely to obtain psychotherapy, suggesting that access to mental health services was better in urban areas than in nonurban areas. Utilization also varied by census region. Policies toward mental health care may vary across states and local governments. It would be interesting to explore these regional effects further.

Both the propensity to use psychotherapy and the portion of out-of-pocket payments declined over time. To some extent, this pattern may reflect the development of safer and more effective antidepressant and anxiety medications that came onto the market in the 1990s (such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors). Thereafter, people were more likely to use pharmacotherapy as their sole treatment for the disorder ( 21 ). But this pattern may also reflect declining benefits over time, leading people to utilize psychotherapy less frequently than before, and when they did seek treatment, only those with more generous therapy coverage (and lower out-of-pocket costs) tended to seek this care.

Most of the differences between Caucasians and Latinos can be explained by observable characteristics, most notably insurance and English language proficiency. In contrast, approximately 50% of the differences in out-of-pocket-payment shares between Caucasians and African Americans reflect unobserved factors. Such unobserved characteristics may include institutional differences (that is, treatment setting), unobserved physician behavior, or cultural factors and beliefs. Future research should recognize that factors that might not be easily observable may nonetheless exert powerful effects on the utilization of psychotherapy services and the cost share burden.

Our results should be interpreted with caution. First, we examined expenditures for and use of psychotherapy services alone. But patients may have used pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy as substitutes for or complements to existing treatment. Thus the lower utilization of psychotherapy does not necessarily mean lower utilization of any mental health services. Second, we examined only office-based psychotherapy. It would be interesting to consider psychotherapy conducted in other settings when appropriate data become available. Third, we explored racial and ethnic disparities among Latinos and African Americans compared with Caucasians. It would be useful to examine how the use and cost of psychotherapy varies for other races, such as Asians. It would also be interesting to see how the use pattern varies among additional Latino subgroups, such as Dominicans, Cubans, and Central and South Americans. Fourth, we used only the broad category of any psychotherapy, without further identifying more specific therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. Finally, although we found that including information on citizenship status did not affect our results, we did not have information on immigrants' legal status, which might have affected the psychotherapy use pattern as well. However, we controlled for interview language and health care access to help minimize this problem.

Conclusions

To reduce utilization disparities in mental health services, policy makers should focus on decreasing language barriers for Latinos. Interpretation services for those who use English as a second language would be helpful. Training more mental health providers in cultural and language issues when working with patients from racial-ethnic minority groups is also important for decreasing these disparities. Finally, any health care reforms that may affect the mental health coverage available through Medicaid would significantly affect psychotherapy use and expenditure among Latinos and African Americans.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

2. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032, 2001Google Scholar

3. Alegría M, Chatterji P, Wells K, et al: Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psychiatric Services 59:1264–1277, 2008Google Scholar

4. Sue S, Zane N, Young K: Research on psychotherapy with culturally diverse populations; in Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed. Edited by Bergin AE, Garfield SL. New York, Wiley, 1994Google Scholar

5. Dobalian A, Rivers P: Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 35:128–141, 2008Google Scholar

6. Sentell T, Shumway M, Snowden L: Access to mental health treatment by English language proficiency and race/ethnicity. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(suppl 2):289–293, 2007Google Scholar

7. Norcross JC, Goldfried MR: Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration (Clinical Psychology), 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2005Google Scholar

8. Jonghe F, Hendricksen M, Dekker J: Psychotherapy alone and combined with pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 185:37–45, 2004Google Scholar

9. AreanP, CookB: Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late life depression. Biological Psychiatry 52:293–303, 2002Google Scholar

10. Delgado P, Alegría M, Cañive J, et al: Depression and access to treatment among US Latinos: review of the literature and recommendations for policy and research. Focus 4:38–47, 2006Google Scholar

11. Mallinger JB, Fisher SG, Brown T, et al: Racial disparities in the use of second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 57:133–136, 2006Google Scholar

12. Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC: Disparities in the adequacy of depression treatment in the United States. Psychiatric Services 55:1379–1385, 2004Google Scholar

13. Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McConagle KA, et al: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:979–986, 1994Google Scholar

14. Blazer DG, Hybels GF, Simonsick EM, et al: Marked differences in antidepressant use by race in elderly community sample: 1986–1996. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1089–1094, 2000Google Scholar

15. Chen J, Rizzo J: Racial and ethnic disparities in antidepressant drug use. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 11:155–165, 2008Google Scholar

16. Givens JL, Houston TK, Van Voorhees BW, et al: Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry 29:182–191, 2007Google Scholar

17. Wittink MN, Joo JH, Lewis LM, et al: Losing faith and using faith: older African Americans discuss spirituality, religious activities, and depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 24:402–407, 2009Google Scholar

18. Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, et al: Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 12:431–438, 1997Google Scholar

19. Briffault X, Sapinho D, Villamaux M, et al: Factors associated with use of psychotherapy. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43:165–171, 2008Google Scholar

20. Olfson M, Marcus S, Druss B, et al: National trends in the use of outpatient psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1914–1920, 2002Google Scholar

21. Wilk JE, West JC, Rae DS, et al: Patterns of adult psychotherapy in psychiatric practice. Psychiatric Services 57:472–476, 2006Google Scholar

22. MEPS HC-105: 2006 Full Year Consolidated Data File. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008. Available at www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h105/h10doc.pdf Google Scholar

23. Jones AM: Health econometrics; in Handbook of Health Economics. Edited by Culyer AJ, Newhouse JP. Amsterdam, North-Holland, 2000Google Scholar

24. Andersen R: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

25. Wooldridge J: Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 4th ed. Boston, South-Western College Pub, 2008Google Scholar

26. Blinder AS: Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. Journal of Human Resources 8:436–455, 1973Google Scholar

27. Oaxaca R: Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. International Economic Review 14:693–709, 1973Google Scholar

28. Fairlie R: An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 10:305–316, 2005Google Scholar

29. Jann B: The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata Journal 8:453–479, 2008Google Scholar

30. Vargas A, Fang H, Rizzo H, et al: Understanding observed and unobserved health care access and utilization disparities among US Latino adults. Medical Care Research and Review 66:561–577, 2009Google Scholar

31. Oquendo MA: Psychiatric evaluation and psychotherapy in the patient's second language. Psychiatric Services 47:614–618, 1996Google Scholar

32. Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, et al: Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Medical Care 40:52–59, 2002Google Scholar

33. Flores G: Language barriers to health care in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 355:229–231, 2006Google Scholar

34. Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, et al: Use of mental health services and subjective satisfaction with treatment among Black Caribbean immigrants: results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health 97:60–67, 2007Google Scholar

35. Stockdale S, Lagomasino I, Siddique J, et al: Ethnic disparities in detection and treatment of depression and anxiety among psychiatric and primary health care visits, 1995–2003. Medical Care 46:668–677, 2008Google Scholar

36. Alegría M, Cao Z, McGuire TG, et al: Health insurance coverage for vulnerable populations: contrasting Asian Americans and Latinos in the United States. Inquiry 43:231–254, 2006Google Scholar

37. Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, et al: Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health 97:76–83, 2007Google Scholar

38. Derose KP, Baker DW: Limited English proficiency and Latinos' use of physician services. Medical Care Research and Review 57:76–91, 2000Google Scholar

39. McGuire T, Miranda J: New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: policy implications. Health Affairs 27:393–403, 2008Google Scholar

40. Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, et al: Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services 54:219–225, 2003Google Scholar

41. Need to increase Latino psychologists in US. Blogspot, Latino Journal E-News, Sept 7, 2008. Available at thelatinojournal.blogspot.com/2008/09/need-to-increase-latinopsychologists.html . Accessed July 14, 2009 Google Scholar

42. Vega C, Moon JR, Aspy CB, et al: A case study in integration. Behavioral Health Management July:34–37, 1999Google Scholar

43. Zuvekas SH, Fleishman JA: Self-rated mental health and racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use. Medical Care 46:915–923, 2008Google Scholar

44. Magaña S: Mental retardation research methods in Latino communities. Mental Retardation 38:303–315, 2000Google Scholar