Implementing the Illness Management and Recovery Program in Japan

Over the past decade the transition from hospital to community-based care has been an objective of mental health policy in Japan. The aim is to gradually reduce the number of beds occupied by psychiatric patients while increasing accessibility to medical and social services in the community ( 1 ). In reality, the transition has been slow.

The 1991 national statistics on psychiatric beds in Japan showed a record high of 29.8 psychiatric beds per 10,000 population. The most recent statistics (2006) show that there are still 27.6 psychiatric beds per 10,000 population. In addition, 68% of inpatients were hospitalized for more than a year ( 1 ). Another study estimated that approximately 70,000 patients were deemed ready for discharge but remained in psychiatric hospitals because they lacked independent living skills and adequate placement options in the community ( 2 ). Increasing and improving opportunities for employment, housing, and social participation and gaining skills for self-management of illness are critical for achieving a productive life.

Guidelines published in Japan in 2004 for the treatment of schizophrenia recommended psychoeducation programs for patients and family members ( 3 ). However, implementation of psychoeducation programs in usual care settings is still insufficient because there are no standardized evidence-based programs in Japan. Historically, Japanese patients have not been expected to be actively involved in treatment. Many live with their families, and family members have traditionally played an important role in helping patients to receive treatment.

In the United States, the rehabilitation of individuals with psychiatric disabilities is based on the concept of recovery as a core value of services. This concept was introduced in the lay writings of consumers beginning in the 1980s. Illness management and recovery is an intervention that was formulated in the United States as a part of the Evidence-Based Practices Implementation Project ( 4 , 5 ). It is a standardized curriculum-based program designed to provide information and skills for self-management of illness and to help clients with severe mental illness achieve life goals (recovery goals). For patients with mental disorders in Japan, who have limited opportunities to self-manage their illness and work on life goals, this program seems to be a practical approach.

The purpose of this study was to establish the feasibility of implementing the illness management and recovery program for the first time in Japan and to evaluate the outcome for participants in the program. We hypothesized that the program would be effective in helping patients acquire knowledge and skills for self-management of illness; improve function and symptoms; and increase quality of life, life satisfaction, and self-efficacy in community living.

Methods

Six clinicians from our research team (a psychiatrist, a nurse, two clinical psychologists, an occupational therapist, and a psychiatric social worker) participated in a one-day training program in California and one-day training program in Japan to learn about the program and in a two-day workshop in California to learn about the concept of recovery. To share information, the clinicians then initiated two-hour study sessions that were held every two weeks during the preparation and implementation period.

This study was conducted from June 2007 to April 2009 at two outpatient facilities at Yokohama City University Hospital (hospital A) and Yokohama City University Medical Center (hospital B). The study was approved by the ethics committee of Yokohama City University School of Medicine. Participants were thoroughly advised about the study, and written informed consent was obtained.

The program consisted of nine modules ( 4 ). Educational handouts were translated into Japanese by our research team ( 6 ). Our research team introduced the program to psychiatrists at clinical conferences, and primary psychiatrists were then asked to identify and recommend patients who would benefit from participating in the program. We recruited 35 study participants with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia given by their primary psychiatrists according to DSM-IV-TR criteria. Ten of the 35 recruited participants were asked to serve as a comparison group before participating in the program. The 35 participants were offered the illness management and recovery program, and a total of 29 agreed to participate in it: 25 agreed to participate in the program, and four agreed to participate in the program after participation in the comparison group. Six agreed to participate in the comparison group only. During the intervention, four patients (14%) dropped out; therefore, 25 patients completed the program.

We employed group and individual formats. The participants attended a 60- or 90-minute session once or twice a week. Patients were encouraged to participate in the group format, but if a participant had excessive social anxiety, individual sessions were provided. Four groups (groups A, B, C, and D) and six individual formats were organized. The program was provided as a day treatment in groups A and B. Group A consisted of nine patients who were receiving ordinary medication treatment and day treatment services at hospital A, and group B consisted of five participants who were receiving the same treatment at hospital B. For scheduling and administrative reasons, group A (N=8 after one dropout) subsequently served as the intervention group for analyses.

The comparison group consisted of ten participants who were receiving ordinary medication treatment and day treatment services at hospital B at the same time as group A. They were wait-listed for the intervention until group A completed the program. While on the wait-list, they were asked to participate in this study as the comparison group. Four participants in the comparison group who participated in the illness management and recovery program after completing the comparison period were included in group B. In Japan the number of day treatment facilities and users is increasing. Therefore, provision of the program in a day treatment service is the most feasible route for widespread use in Japan.

Group C consisted of six participants, and group D consisted of three participants; both these groups were receiving ordinary medication treatment at hospital A. The six participants who participated in the individual (nongroup) format were receiving ordinary medication treatment at hospital A.

After the four participant groups and the six individual-format participants had completed the third module of the program, the research team used the Illness Management and Recovery Fidelity Scale to assess the adequacy of implementation. (At the time there were no trained fidelity assessors in Japan.) The mean fidelity score for the groups and individuals was 4.90±.17. (Possible scores on this scale range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater adequacy of implementation.)

Baseline and posttreatment assessments for all study participants included several standardized instruments. Participants in the comparison group were assessed at the same time as those in group A. The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) is a standardized assessment of several functional dimensions. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) is a 16-item scale with nine items on general symptoms, five items on positive symptoms, and two items on negative symptoms. The scale's interrater reliability has been validated ( 7 ). The GAF and BPRS were administered to participants by their primary psychiatrists.

The Patient Activation Measure for Mental Health (PAM13-MH) is a 13-item instrument that assesses the activation level in self-management of mental illness. Elements of knowledge, skill, and confidence in self-management are assessed. Research has provided evidence for the scale's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and concurrent validity ( 8 ). The Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-item Health Survey Acute Version (SF-36) is designed to capture self-reported health-related quality of life. The SF-36 yields scores for eight domains (physical functioning, role-physical, role-emotional, general health, social functioning, bodily pain, vitality, and mental health) and a single health utility index. SF-36 has been widely used, and its internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent, discriminant, and construct validity have been established ( 9 ).

The Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) is a 31-item measure that assesses the life satisfaction of patients with mental illness. The LSS yields scores for six domains (life in general, physical functioning, environment, social skills, social relationships, and psychological functioning). Research has provided evidence for the scale's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and concurrent and construct validity ( 10 ). The Self-Efficacy for Community Life Scale for Schizophrenia (SECL) is an 18-item measure that yields scores for six domains (daily living, treatment-related behavior, coping with symptoms, social life, and social relationships). The scale's internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and content, concurrent, construct, and factorial validity have been established ( 11 ). The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire–8 (CSQ-8) is an eight-item measure designed to measure client satisfaction with services. Possible scores range from 8 to 32, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. Research has provided evidence for the scale's internal consistency and criterion-related validity ( 12 ). The PAM13-MH, SF-36, LSS, SECL, CSQ-8 were completed as self-report instruments.

We conducted statistical analyses with t tests for continuous variables using data from baseline to posttreatment for participants who completed the program. Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate whether the illness management and recovery intervention improved particular outcomes compared with usual services (medication and day treatment). This study was quasi-experimental, and assignment to the two groups was not random. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed probability of less than .05, because analyses of domains for each instrument were explorative. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS, version 11.0.

Results

The mean±SD number of months of the intervention was 8.38±1.51, and the mean number of sessions provided to participants was 27.50±3.97. Four intervention participants dropped out: three because they stopped using all outpatient services, and one specifically asked to leave the program.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for participants who completed the program (N=25) were documented. The mean age was 33.02±8.82, 11 (44%) were men, all were unmarried, and 24 (96%) were not working. The mean duration of illness was 10.80±7.30 years. The mean GAF score was 45.26±13.06, and the mean BPRS score was 34.36±9.60. These scores indicated that participants had severe disabilities in general functioning and moderate symptoms.

Changes from baseline to posttreatment for the 25 participants indicated significant improvement in functioning as measured by the GAF (p<.001), in severity of symptoms as measured by the BPRS (p<.01), and in activation level in self-management as measured by the PAM13-MH (p<.01). The health-related quality of life of participants improved in the social functioning domain on the basis of SF-36 scores (p<.05). Participants' satisfaction in various aspects of community living also improved, which was shown by the LSS subscale scores (p<.01). In terms of self-efficacy, two factors—daily living and social relationships—showed significant improvement (p<.05 and p<.001, respectively). The average dosage of antipsychotic medication did not change significantly between baseline and posttreatment (from 6.12±4.40 mg to 5.71±4.21 mg in risperidone equivalents).

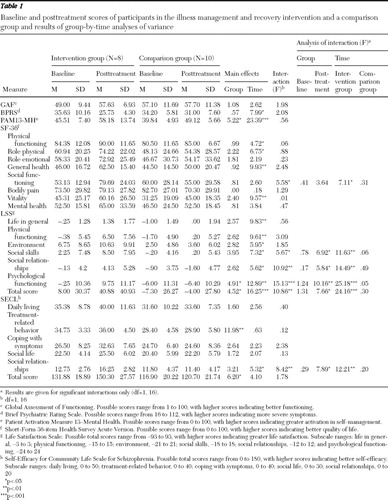

No significant differences were found by Mann-Whitney U test between the eight participants in group A (intervention group) and the ten participants in the comparison group in age, number of hospitalizations, baseline GAF scores, baseline BPRS scores, and average dosage of antipsychotic medication. Duration of illness was significantly longer in the intervention group (p<.05). As shown in Table 1 , the results from group-by-time ANOVA (intervention group and comparison group by baseline and posttreatment) showed significant interaction effects for time and group for the social functioning subscale of the SF-36; for the total score and the LSS subscales of social skills, social relationships, and psychological functioning; and for the SECL social relationships subscale. Analyses of interaction for these variables found significant effects of the group factor for posttreatment and of the time factor for intervention group. Participants in the illness management and recovery program significantly improved on subscales of the SF-36, LSS, and SECL, whereas participants in the comparison group did not change significantly from baseline.

|

The average CSQ-8 score among participants was 26.20±3.86, indicating a high level of satisfaction.

Discussion

In this study, exploratory findings suggested that participants in the illness management and recovery program showed significant improvement in psychiatric symptoms and overall functioning, as well as self-reported improvement in health-related quality of life, activation level for self-management of illness, and satisfaction and self-efficacy in community living. Compared with those in the comparison group, participants in the intervention group, who were all actively engaged in the day treatment program at baseline, showed an increased quality of life in social functioning; increased satisfaction with social skills, social relationships, and psychological functioning; and increased self-efficacy in social relationships in community living. Overall, participant satisfaction was high.

In a study conducted in the United States and Australia, participants in illness management and recovery reported high satisfaction and showed positive changes in illness self-management, hope, global functioning, knowledge, distress related to symptoms, and goal orientation ( 13 ). In another study conducted in the United States, participants reported significant changes in illness self-management and hope ( 14 ). A randomized controlled trial in Israel found that the program was effective in increasing participants' knowledge and progress toward personal goals ( 15 ). These findings are consistent with our findings. Furthermore, our study in Japan suggested that provision of the program at a day treatment service is effective. This is important knowledge for providers in Japan, where provision of this setting is the most feasible route for widespread use.

Previous studies reported increased hope among participants in regard to self and recovery and greater movement toward personal goals ( 14 , 15 ). Although we were not able to objectively measure personal feelings of achievement, most of the participants in our study reported subjective progress toward their personal recovery goals. A variety of achievements were reported, including being employed and having richer daily living experiences, more opportunities to go out, and a wider variety of social relationships.

Previous studies have documented dropout rates from 10% to 50% ( 13 , 14 , 15 ). The rate in our study was relatively low (14%). Of the four individuals who dropped out, only one dropped out for a reason directly related to the program. That patient complained that the educational handouts were too difficult to understand, and she felt that her lack of progress was being unfavorably compared with the progress of other participants. It would have been helpful to elicit more feedback from the other individuals who discontinued the program to help ensure that it is responsive to the needs of all participants.

Participants who were participating in day treatment had easy access to the program. For those not participating in day treatment, the program could be provided in a variety of settings, including outpatient treatment facilities and community support centers.

The study had several limitations. The sample was small, the participants were not randomly assigned to treatment, the objective assessments were not obtained by blind interviews, and the long-term effects of the program need to be investigated. Additional research is needed to validate our findings.

Conclusions

This study suggests that the illness management and recovery program is an effective program for participants with severe mental illness in Japan. The promising outcomes of our study suggest that more rigorously controlled research on the effects of the program is warranted. We hope to provide the program to many individuals with psychiatric difficulties in Japan and help them move toward achieving their personal recovery goals.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study was supported in part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 21791141 from the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology; Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 0990890031 from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare; a grant from Pfizer Health Research Foundation, Japan; and a grant from the Research Group for Schizophrenia, Japan.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Mental Health and Welfare Data in Japan, 2006 [in Japanese]. Tokyo, Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, 2006Google Scholar

2. Isolated 550,000 Consumers With Mental Illness [in Japanese]. Tokyo, Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Hirakawa H Research Division, Jan 6, 2009Google Scholar

3. Sato M, Inoue S: Guideline for Treatment of Schizophrenia [in Japanese]. Tokyo, Igaku-Shoin, 2004Google Scholar

4. Gingerich S, Mueser K: Illness Management and Recovery. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2003. Available at mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/cmhs/communitysupport/toolkits/illness Google Scholar

5. Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behavior Modification 27:387–411, 2002Google Scholar

6. Fujita E, Kuno E, Suzuki Y, et al: Introduction of Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) [in Japanese]. Seishin Igaku 50:709–715, 2008Google Scholar

7. Miyata R, Fujii Y, Inagaki A, et al: Reliability of the Japanese version of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scales (BPRS) [in Japanese]. Rinsho Hyoka 23: 357–367, 1995Google Scholar

8. Fujita E, Kato D, Kuno E, et al: Development and validation of the Japanese version of the Patient Activation Measure 13 for Mental Health [in Japanese]. Seishin Igaku, Seishin Igaku 52:765–772, 2010Google Scholar

9. Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, et al: Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 51:1037–1044, 1998Google Scholar

10. Kadoya K: Development of life satisfaction scale for evaluating the quality of life of patients with mental illness [in Japanese]. Journal of Kyoto Prefectual University of Medicine 104:1413–1424, 1995Google Scholar

11. Okawa N: Development of Self Efficacy for Community Life Scale for Schizophrenia: reliability and validity [in Japanese]. Seishin Igaku 43:727–735, 2001Google Scholar

12. Tachimori H, Ito H: Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of Client Satisfaction Questionnaire [in Japanese]. Seishin Igaku 41:711–717, 1999Google Scholar

13. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al: The Illness Management and Recovery program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:32–43, 2006Google Scholar

14. Salyers MP, Godfrey JL, McGuire AB, et al: Implementing the illness management and recovery program for consumers with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 60:483–490, 2009Google Scholar

15. Hasson-Ohayon I, Roe D, Kravetz S: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program. Psychiatric Services 58:1461–1466, 2007Google Scholar