Correlates of Perceived Need for Mental Health Care Among Active Military Personnel

Theoretical models of help-seeking behavior suggest that people progress through several stages before seeking mental health care ( 1 , 2 ). These stages include experiencing symptoms, evaluating the severity and consequences of symptoms, assessing whether treatment is required, assessing the feasibility of and options for treatment, and deciding whether to seek treatment ( 2 ). Studies of general population samples in several countries have increasingly focused on understanding the prevalence and correlates of self-perceived need for mental health treatment ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). These studies have shown that there is not a close relationship between a DSM diagnosis, self-perceived need for mental health treatment, and mental health service use ( 3 , 6 , 7 ). In the general population, a range of sociodemographic factors, chronic physical conditions, suicidal ideation, and exposure to childhood traumatic events have been found to be associated with self-perceived need for mental health treatment ( 5 , 8 ).

Emerging data suggest that active military personnel have high rates of mental disorders and self-perceived need for mental health care, as well as somatic complaints ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ). As in research on the general population, the few epidemiologic studies in military samples have demonstrated that most military personnel who meet criteria for one or more mental disorders do not perceive a need for mental health treatment or receive any mental health services ( 12 , 13 ). In addition, our previous work in a military population showed that self-perceived need for mental health care was differentially associated with type of mental disorder diagnosis ( 13 ). Panic disorder had the strongest association with perceived need, and alcohol dependence had the weakest association.

There are two specific limitations of the literature on perceived need for mental health care among active military personnel. First, no systematic evaluation of the correlates of self-perceived need has been conducted in an active military population. Military culture may attract soldiers who are "invulnerable heroes" who believe in a specific cause and who may not receive support from leaders in regard to their mental health issues. Therefore, the prevalence and correlates of self-perceived need for mental health care found in civilian populations may not apply to military populations. Second, evidence is emerging that deployment-related factors, such as exposure to combat ( 14 ), longer deployments ( 15 ), and type of service personnel (regular or reserve) ( 16 ), are associated with the onset of mental disorders and perceived need. However, it remains unclear which sociodemographic, deployment-related, and disability variables are associated with self-perceived need for mental health care after adjustment for the effects of common axis I mental disorders.

To address these limitations, we utilized a large population-based sample of active military personnel, the Canadian Community Health Survey Cycle 1.2 Canadian Forces Supplement (CCHS-CFS 1.2) ( 13 ). This survey is unique because it used a well-validated measure of perceived need called the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ). This measure assesses whether the respondent feels that care is needed and determines the form of care need: information, medication, counseling, social intervention, or skills training. The PNCQ has been validated and used in clinical and epidemiologic general population samples ( 3 , 4 , 17 ).

The study reported here had three specific objectives. First, we examined sociodemographic and military duty characteristics associated with perceived need. Second, we explored mental disorder correlates, quality of life, and suicidality in relation to perceived need. Finally, we aimed to determine the unique associations between several deployment-related factors and self-perceived need after we adjusted for the presence of common mental disorders.

Methods

Survey

Data were from a cross-sectional population-based survey of Canadian Forces personnel collected between May and December 2002 ( 13 ). The CCHS-CFS 1.2 employed a multistage sampling framework to ensure the representativeness of the sample in relation to the Canadian military (details of the sampling frame of the survey are available on request) ( 13 ). The sample consisted of 5,155 regular force members (response rate 80%) and 3,286 reserve force members (response rate 84%). Reserve members were included in the target population if they had been active in the Canadian Forces in the six months before data collection.

To preserve anonymity, no information was available about the specific deployment location of these soldiers. However, on the basis of the age range of the sample, it is likely that the soldiers were involved in several missions, including those to Iraq (the first Gulf War), Rwanda, Somalia, and the former Yugoslavia.

Measures

Perceived need for mental health care. The PNCQ, developed by Meadows and colleagues ( 4 , 17 ), was included in the CCHS-CFS 1.2. Data on the reliability and validity of the PNCQ have been previously reported. The PNCQ assesses whether in the past year a respondent perceived a need or received help for problems with emotions, mental health, or use of alcohol or drugs. Five types of need are assessed: information about mental health problems and available treatments and services, medication, therapy or counseling, social intervention (for financial or housing problems), and skills training (for employment status, work situation, or personal relationships).

Sociodemographic factors. Sociodemographic factors assessed included sex, age, marital status, income, education, military rank (junior, senior, or officer), type of service (regular or reserve), and type of personnel (land, air, sea, or communications).

Deployment variables. Deployment was defined as "deployed in support of a mission, such as a NATO mission or a UN tour. These deployments must be of at least 3 months duration." Number of deployments was assessed: "How many deployments lasting 3 months or more have you had in your career? Include deployments as a regular or reserve Canadian Forces member." Participants could endorse zero, one, two, three, four, or five or more deployments. Any individual who indicated one or more deployments was classified as having been deployed. Another question with a dichotomous response assessed the tempo of deployment: "During your career, was there ever a period of less than 12 months between the time you completed one deployment and the time you started another?" The notice given to the participant before deployment was also assessed: "Thinking about your most recent deployment, how much notice did you receive prior to the deployment?" Participants could choose less than one month, one to three months, four to six months, or more than six months. Family members' concerns about deployment were assessed: "Did your immediate family express any concerns regarding this deployment?" A single question examined whether the participant had ever been deployed as an augmentee, defined as being "deployed with a unit other than [his or her] home unit." Finally, participants reported the length of time away from home because of work-related activities (zero to five months, six to 12 months, and more than 12 months).

Separate questions were asked about combat exposure, peacekeeping operations, and witnessing atrocities. In conjunction with the deployment variable, we created a three-level categorical variable to account for different types of deployment-related experiences (not deployed, deployed with no exposure to combat or atrocities, and deployed with exposure to combat or atrocities). Because our previous work emphasized the poor mental health outcomes related to combat and witnessing atrocities ( 13 ), these events were grouped together and separate from peacekeeping operations.

Mental disorders. The content of the survey was partly based on a selection of mental disorders from the World Mental Health Survey initiative (WMH 2000) ( 18 , 19 , 20 ). The World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 2.1 was used to generate diagnoses according to both ICD-10 and DSM-IV definitions and criteria. The CIDI is a fully structured instrument for use by lay interviewers who do not have clinical experience; it has high levels of reliability and consistency with the clinician-based diagnoses of DSM disorders assessed in this survey. The interviewers were trained according to WMH 2000 standards ( 20 ). The CCHS-CFS 1.2 methodology has been described elsewhere ( 21 ). Past-year prevalence rates of five DSM-IV mental disorders were assessed: major depressive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The CIDI Short Form was used to assess alcohol dependence based on DSM-IV criteria; three symptoms or more indicated alcohol dependence ( 22 ).

Long-term restriction of activities. Participants were asked if a long-term physical health condition, mental health condition, or health problem had reduced the amount or kind of activity "at home," "at school," "at work," or "in other activities, for example, transportation or leisure." For each of the areas of reduced functioning, the respondent had the choice of sometimes, often, or never. Because of the skewed distribution of this variable, it was dichotomized. Respondents endorsing never for all areas of functioning were categorized as "not restricted," and the others were categorized as "restricted."

Past-year suicidal ideation. Participants were asked whether they had seriously thought about committing suicide in the past 12 months.

Analyses

To account for the design effects of the CCHS-CFS 1.2 and to ensure that the data are representative of the Canadian Forces target population, Statistics Canada recommends a bootstrap procedure that uses a set of replicate weights supplied by Statistics Canada. For all analyses, we provide the unweighted Ns that are based on the interviewed sample (N=8,441). All percentages and regression analyses are based on the weighted sample, which takes nonresponse into account and provides estimates that are generalizable to the Canadian military population. Design-based standard errors and confidence intervals were also calculated by the bootstrap. All analyses were performed using SUDAAN, version 9.0.1 ( 23 ).

Using multiple logistic regression analyses, we examined the correlates of perceived need for care in models unadjusted and adjusted for mental disorders. For the adjusted models, we entered each past-year disorder separately as a covariate (major depression, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, PTSD, and alcohol dependence). Because of the multiple comparisons, we used a conservative alpha of .01 for statistical significance. Previous work has suggested that adjustment for multiple tests (for example, the Bonferroni correction) is not required for these types of analyses ( 24 ); however, we felt that given the number of analyses a more conservative approach was appropriate.

Results

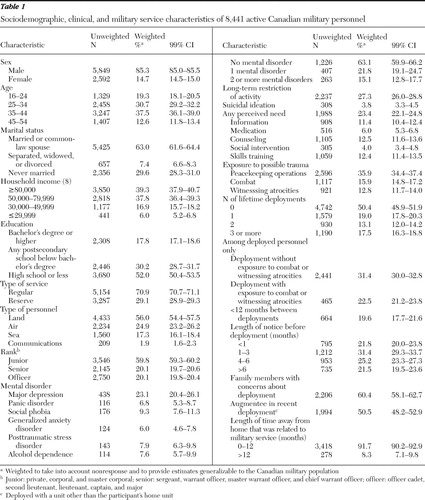

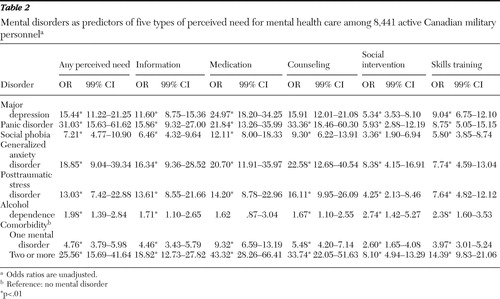

Table 1 presents data on the sociodemographic, clinical, and military service characteristics of the sample. Table 2 shows the relationship between perceived need for mental health care and each type of mental disorder examined and comorbid mental disorders. Panic disorder had the strongest association with perceived need. Each mental disorder was associated with each type of perceived need, with the exception of alcohol dependence, which was not associated with perceived need for medication. Having comorbid mental disorders was also strongly associated with perceiving need for care.

|

|

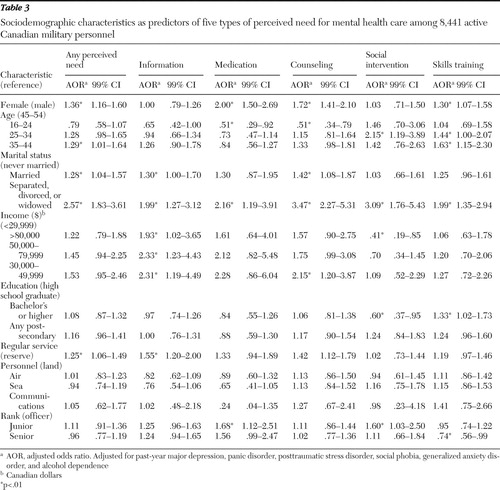

Table 3 presents data on the association of sociodemographic factors with each of the subtypes of perceived need, adjusted for mental disorders. (Unadjusted models are not presented for the sake of brevity, but are available from the authors on request.) Female sex, age range of 35–44, marital status other than never married, middle income, regular service membership, and junior rank were positively associated with self-perceived need for mental health treatment. These findings were not consistent across each of the subtypes of perceived need. Participants with a higher income were more likely to report perceived need for information but less likely to perceive a need for skills training.

|

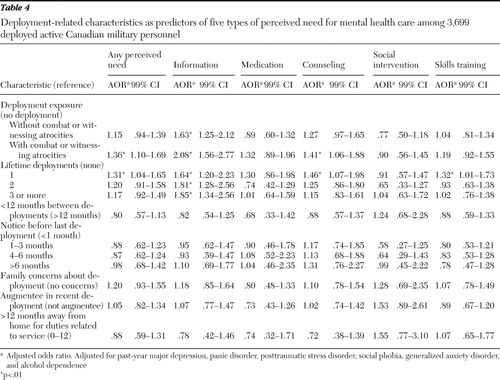

Table 4 presents data on the association between deployment-related variables and perceived need. After adjustment for mental disorders, lifetime deployment with exposure to combat and witnessing atrocities and the number of deployments were associated with any perceived need and perceived need for information and for counseling. Deployment without exposure to combat and to witnessing atrocities was associated only with perceived need for information. Length of deployment and time between deployments did not predict perceived need.

|

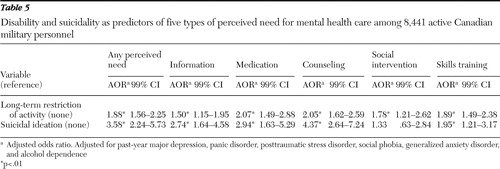

Data in Table 5 indicate that long-term restriction of activities and past-year suicidal ideation were strongly associated with perceived need. These factors were associated with each type of perceived need.

|

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide a detailed examination of the correlates of self-perceived need for mental health treatment in an active military sample. The study adds to the literature by delineating a range of correlates of perceived need, including sociodemographic, deployment-related, and disability variables and suicidality.

The findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, although mental disorders and perceived need were assessed with standardized, validated measures, these measures may not be as accurate as clinician-based assessments. Second, because of the cross-sectional nature of the study, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Third, although alcohol dependence was assessed in the survey, alcohol abuse, a prevalent mental health problem in military populations, was not assessed ( 25 ). The lack of adjustment for alcohol abuse may have affected some of the associations. However, many of the associations shown between perceived need and sociodemographic factors, disability, and suicidality have been found in previous general population samples in which alcohol abuse was included as a covariate ( 5 , 6 ). Fourth, other mental disorders, such as drug use disorders and personality disorders, were not assessed and may have had an impact on some of the associations. Finally, the findings may not be generalizable to military populations in other countries because of differences in recruitment and selection processes, as well as differences in health care systems. In the context of these limitations, there are several important findings.

First, this study is the first to show that being deployed with exposure to combat or witnessing atrocities was associated with an increased likelihood of perceived need for mental health care, even after the analyses adjusted for common mental disorders. Also, deployment without exposure to combat was associated with perceived need for information. These findings suggest that soldiers returning from deployment should be assessed not only for mental disorders ( 26 ) but also for self-perceived need for mental health treatment. Previous work has shown that people may perceive a need for mental health treatment or seek treatment even though they do not meet criteria for a mental disorder ( 7 , 13 , 27 ). Although there has been concern that this subgroup may use services inappropriately, studies have suggested that self-perceived need for treatment even in the absence of an assessed mental disorder is associated with reduced quality of life, disability, and suicidality ( 7 , 13 , 27 ). Some individuals without assessed mental disorders may fall short of DSM thresholds but may still be significantly distressed or impaired by their symptoms. Data from this study suggest that there is a need to screen for self-perceived need for mental health care.

On the other hand, several deployment factors that have been shown in other studies to be associated with distress and mental disorders ( 28 , 29 ), such as the tempo of deployment, duration of deployment, and concerns from family members about deployment, were not associated with an increased likelihood of perceived need. These findings might be attributable to actual differences between the correlates of distress and perceived need or might be related to differences in exposure to stress between Canadian soldiers and other military samples from the United States and United Kingdom.

Second, long-term restriction in activities was among the strongest correlates of perceived need for mental health treatment. This finding is consistent with increasing evidence of a strong relationship between disability and perceived need in general population samples ( 5 ). Restriction in activities may be especially problematic for military personnel who need to be physically fit in order to be deployed and to carry out a number of occupation-related duties. Physical injury, pain, and disability are strongly associated with PTSD related to combat and peacekeeping operations ( 10 , 30 , 31 ). Our findings suggest that long-term disability is independently associated with self-perceived need for treatment even after adjustment for common mental disorders. These findings also suggest that physically injured or disabled soldiers should be carefully screened for self-perceived need for mental health treatment and, if appropriate, offered treatment to reduce their symptom burden with the aim of increasing functionality.

Third, suicidal ideation was strongly associated with perceived need. Although suicidal ideation often develops in the context of a mental disorder, it can occur in the context of significant interpersonal stress, poor coping, and personality disorders. The survey did not assess participants for personality disorders. It is possible that the association between suicidal ideation and perceived need is mediated by personality disorders. Further studies are required to explore this link.

Fourth, several sociodemographic factors (age, female gender, and marital status), mental disorders, and comorbidity of mental disorders were associated with perceived need in this military sample. These associations were consistent with previous findings in general population samples ( 3 , 5 , 6 ). Men in this study were less likely than women to perceive any overall need or any need for medications or counseling. More work, ideally with multiple informants (clinician assessment and assessment of family members), needs to be done to examine the accuracy of lower self-perceived need for mental health care among men. It is important to note that most military samples consist largely of men. Studies of large samples of male military veterans have demonstrated that negative perceptions of mental health treatment among leadership and unit members and being perceived as weak are the most commonly reported barriers to mental health care ( 12 , 13 , 32 ). Few data exist on optimal methods of reducing these types of barriers. However, a recent study found that soldiers endorsed encouragement by family members and friends as a preferred approach to reducing barriers to mental health care ( 32 ).

Finally, this study showed that marital status was associated with perceived need, even after adjustment for common mental disorders. Compared with never being married, being separated or divorced had the strongest positive associations with all of the perceived-need variables, whereas being married was less consistently associated with perceived need. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies in general population samples ( 5 ) and suggest that the stress of marital breakups can precipitate consideration of mental health treatment. In addition, being married may also be stressful for soldiers who are deployed away from their families for several months. Absence from home might be associated with marital discord as well as separation and divorce. Family-based interventions may help military families cope with deployments.

Conclusions

This study examined the correlates of self-perceived need for mental health care in a nationally representative sample of Canadian soldiers. In addition to common mental disorders, lifetime deployment, certain sociodemographic factors, disability, and suicidality were found to be associated with perceived need. The study adds to the literature suggesting that soldiers should be screened not only for common mental disorders but also for self-perceived need for mental health care. The findings also add to the growing body of literature in civilian populations indicating the importance of assessing self-perceived need for mental health care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Preparation of this article was supported by New Emerging Team Grant PTS-63186 from Mental Health and Addiction, Institute of Neurosciences, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); a CIHR operating grant; CIHR New Investigator Grant 152348; Career Development (K24) Award MH64122 from the National Institutes of Health to Dr. Stein; a CIHR Investigator Award to Dr. Sareen; and a Fredrick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship-Doctoral Award to Ms. Belik. The opinions expressed in this article do not represent the opinions of Statistics Canada.

1. Andersen RJ: National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Medical Care 46:647–653, 2008Google Scholar

2. Goldberg D, Huxley P: Mental Health in the Community: The Pathways to Psychiatric Care. London, Tavistock, 1980Google Scholar

3. Meadows G, Burgess P, Bobevski I, et al: Perceived need for mental health care: influence of diagnosis, demography and disability. Psychological Medicine 32:299–309, 2002Google Scholar

4. Meadows G, Burgess P, Fossey E, et al: Perceived need for mental health care, findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Psychological Medicine 30:645–656, 2000Google Scholar

5. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77–84, 2002Google Scholar

6. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Perceived need for mental health treatment in a nationally representative Canadian sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:447–455, 2005Google Scholar

7. Sareen J, Stein MB, Campbell DW, et al: The relationship between perceived need for mental health treatment, DSM diagnosis and quality of life: a Canadian population-based survey. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:173–180, 2005Google Scholar

8. Sareen J, Fleisher W, Cox BJ, et al: Childhood adversity and perceived need for mental health care: findings from a Canadian community sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 193:396–404, 2005Google Scholar

9. Hotopf M, Hull L, Fear NT, et al: The health of UK military personnel who deployed to the 2003 Iraq war: a cohort study. Lancet 367:1731–1741, 2006Google Scholar

10. Hoge CW, Terhakopian A, Castro CA, et al: Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:150–153, 2007Google Scholar

11. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS: Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295:1023–1032, 2006Google Scholar

12. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351:13–22, 2004Google Scholar

13. Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al: Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care: findings from a large representative sample of military personnel. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:843–852, 2007Google Scholar

14. Dohrenwend BP, Turner JB, Turse NA, et al: The psychological risks of Vietnam for US veterans: a revisit with new data and methods. Science 313:979–982, 2006Google Scholar

15. Rona RJ, Fear NT, Hull L, et al: Mental health consequences of overstretch in the UK armed forces: first phase of a cohort study. British Medical Journal 335:603–604, 2007Google Scholar

16. Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW: Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq War. JAMA 298:2141–2148, 2007Google Scholar

17. Meadows G, Harvey C, Fossey E, et al: Assessing perceived need for mental health care in a community survey: development of the Perceived Need for Care Questionnaire (PNCQ). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:427–435, 2000Google Scholar

18. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593–602, 2005Google Scholar

19. Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:93–121, 2004Google Scholar

20. Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, et al: Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:122–139, 2004Google Scholar

21. Gravel R, Beland Y: The Canadian Community Health Survey: mental health and well-being. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 50:573–579, 2005Google Scholar

22. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171–185, 1998Google Scholar

23. SUDAAN, release 9.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 2005Google Scholar

24. Bender R, Lange S: Adjusting for multiple testing: when and how? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 54:343–349, 2001Google Scholar

25. Jacobson IG, Ryan MA, Hooper TI, et al: Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA 200:663–675, 2008Google Scholar

26. Seal KH, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, et al: Getting beyond "Don't ask; don't tell": an evaluation of US Veterans Administration postdeployment mental health screening of veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. American Journal of Public Health 98:714–720, 2008Google Scholar

27. Druss BG, Wang PS, Sampson NA, et al: Understanding mental health treatment in persons without mental diagnoses: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:1196–1203, 2007Google Scholar

28. Bartone PT, Adler AB, Vaitkus MA: Dimensions of psychological stress in peacekeeping operations. Military Medicine 163:587–593, 1998Google Scholar

29. Adler AB, Huffman AH, Bliese PD, et al: The impact of deployment length and experience on the well-being of male and female soldiers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 10:121–137, 2005Google Scholar

30. Asmundson GJG, Stein MB, McCreary DR: Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms influence health status of deployed peacekeepers and nondeployed military personnel. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190:807–815, 2002Google Scholar

31. Grieger TA, Cozza SJ, Ursano RJ, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in battle-injured soldiers. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1777–1783, 2006Google Scholar

32. Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Mullen K, et al: Soldier attitudes toward mental health screening and seeking care upon return from combat. Military Medicine 173:563–569, 2008Google Scholar