Public Awareness Campaigns About Depression and Suicide: A Review

Suicide prevention is an international public health priority, and many countries have established national action plans ( 1 , 2 ) that combine various strategies to prevent suicidal behavior ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ). Numerous institutions, including the World Health Organization, recommend targeting education campaigns to the general public to improve awareness of suicidal crises and, more broadly, to improve awareness of depression ( 11 , 12 ), which is a major risk factor for suicidal behavior ( 13 , 14 ). Lack of public information and stigmatization of persons with depression are major barriers to care and to the occupational and social integration of these individuals ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). Given the increasing use of campaigns to heighten public awareness and disseminate information, it is important to assess the effectiveness of these efforts in changing population attitudes and behaviors ( 19 , 20 , 21 ).

At the request of the French Southeast Regional Health and Welfare Bureau, we conducted a literature review with the goal of describing public awareness and information campaigns conducted that focus on depression or suicide and that aim to reduce suicide rates or the discrimination that limits care seeking by persons in need. A second goal of the review was to assess the effectiveness of these campaigns in changing attitudes and behaviors.

Methods

We searched for articles and reports published between 1987 and 2007, using MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, HDA (Health Development Agency) Evidence Base, DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects), and ISI Web of Science. The following keywords, separately or in combination, were used: suicide, mental health, depression, mass media, health promotion, health education, and evaluation. We also examined references in the identified publications.

We selected publications in English about public information and awareness programs that focused specifically on depression or suicide or that addressed mental illness more generally if the program included specific educational components on depression or suicide and reported evaluation data—either pre- and posttest evaluations or evaluations that involved a comparison group and defined objectives, target populations, assessment tools, and indicators. Programs delivered in schools or directed solely at health care professionals were excluded, because they were included in recent reviews ( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ). When a publication described a program that was addressed to both professionals and the general public, we present only the results concerning the public.

Results

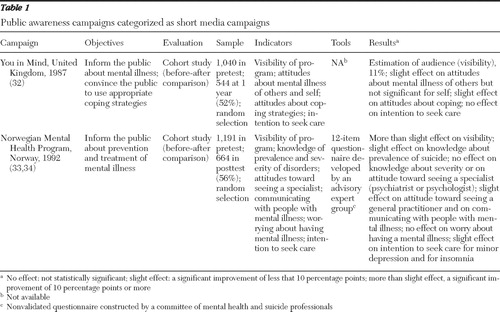

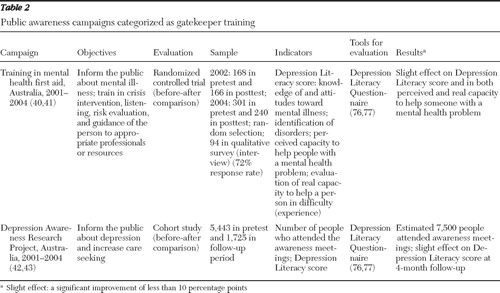

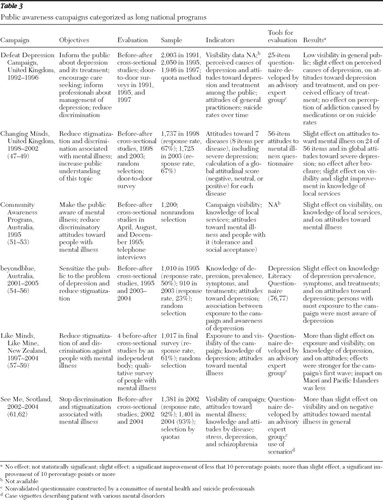

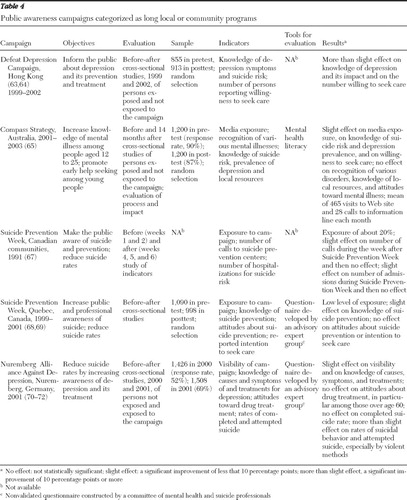

The search yielded 200 reference citations, and 43 of the cited publications met our inclusion criteria. They covered 15 programs in eight countries. We found publications describing U.S. programs, but we did not include them in the review because they did not meet our inclusion criteria. We classified the programs into four categories: short media campaigns, which involved a single exposure ( 32 , 33 , 34 ) ( Table 1 ); gatekeeper training programs ( 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ) ( Table 2 ); and long programs involving repeated exposures, conducted on either a national scale ( 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 ) ( Table 3 ) or a local scale ( 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 ) ( Table 4 ). In addition to describing the programs, the tables present evaluation information. Almost all the programs sought to improve knowledge about depression or suicidal crises—that is, at a minimum the program had one or both of these specific aims—and to reduce discrimination, counter misconceptions, and enhance help seeking. Only three programs, all local, were aimed specifically at reducing suicide risks ( 67 , 68 , 71 ).

|

|

|

|

Short media campaigns

Table 1 describes programs in the category of short media campaigns. A television series called You in Mind was broadcast in the United Kingdom in 1987 to sensitize the public about mental illness ( 32 ). Seven ten-minute episodes covered various topics—for example, Overcome Your Depression, Overcome Your Fears, and Express Your Feelings—and showed the audience examples of coping strategies. They offered a positive presentation of people describing their problems and how they deal with them. An information booklet about the topics covered and mental health services was available on request. The evaluation found that 11% of the people questioned had seen the program and they reported that it had a positive impact on their attitudes toward mental illness. Three-quarters of respondents reported that the portraits of individuals with mental illness in the series resembled people they knew. In addition, half the respondents reported that as a result of what they learned from the series, they had tried—or intended to try—to deal with their own mental health problems in a way that they had not done so in the past.

The Norwegian Mental Health Program was conducted in Norway in 1992 to improve public understanding of mental illnesses (including depression) and suicide and to diminish taboos about them ( 33 , 34 ). Its primary component was a six-hour information program that was broadcast during prime time on a national network. The broadcast was preceded by a month-long publicity campaign. The articles reviewed provide no details about how the campaign addressed depression. The evaluation showed that 94% of the people questioned reported that they had heard of the program and 62% had watched it. The proportion of people who correctly reported the ratio of mortality by suicide to mortality by traffic accidents increased; among men, the proportion increased from 28% before the campaign to 49% afterward (p<.001), with a similar but nonsignificant trend among women. In contrast, knowledge of the prevalence of mental illness and treatment sites did not improve significantly. The results suggest that viewers had a greater tolerance for mental illness after the program. Before the program 74% of women respondents reported being willing to talk openly about a close friend or family member admitted to a psychiatric hospital, and the proportion rose to 81% after the campaign (p<.01), with a similar but nonsignificant trend among men. After the program, the proportion of respondents who reported that they would recommend that someone close to them see a general practitioner in the case of a minor psychiatric disorder—notably symptoms of depression—increased from 19% to 31% among men (p< .001) and from 22% to 34% among women (p<.001).

Gatekeeper training

Gatekeeper training—training community members to identify people with problems and direct them toward assistance—has been applied in the workplace, in the military, ( 35 , 36 , 37 ), and among police officers ( 38 ). It has been shown to reduce suicide rates ( 35 , 36 , 38 ) and suicide risks ( 37 ). Because these programs targeted specific occupations, they are not described in Table 2 , which presents information on programs in the gatekeeper training category.

The 1997 Australian Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing showed that a substantial proportion of individuals did not know how to behave with people who have mental illness, especially during crises ( 39 ). The "mental health first aid" program was set up in 2001 in Australia to teach professionals and the general population how to help "a person developing a mental health problem or in a mental health crisis … until appropriate professional treatment is received or until the crisis resolves." The course, initially nine hours long and subsequently expanded to 12 hours, described steps for providing early help to adults in crisis situations or developing a mental illness: assess the risk level, listen nonjudgmentally, reassure and inform, and encourage the person to see a professional. By the end of 2007 a total of 600 instructors had been trained in Australia. The program has been replicated in numerous countries. Successive assessments suggest that the training increases participants' capacity to recognize mental illness, raising their knowledge to a level close to that of mental health professionals, and reduces stigmatizing attitudes and social distance between participants and people with mental illness ( 40 , 41 ). After training, participants reported increased confidence that they could help people in crisis. The improvements continued to be evident at six-month follow-up ( 40 ). A qualitative study of former participants' experiences showed that 78% had used what they learned in the mental health first aid program to help people and 79% were sure that they had been able to help people with problems ( 41 ).

A program of this type was set up in the Australian state of Victoria from 2001 to 2004. The Depression Awareness Research Project sought to make communities aware of depression and to reduce its associated stigma ( 42 , 43 ). The principle was to recruit and train "educators"—more than 200 in three years—who were then assigned to lead awareness meetings within their communities. The following key messages were delivered: depression is common, it is a disease and not a charactertrait, and it is a serious but treatable disease. The evaluation indicated that among people who attended the community meetings, mental health education levels remained significantly elevated four months later.

Long national programs

Table 3 provides information on long national programs. Most long programs used several concomitant strategies, including, for example, screening, professional training, media education, and restriction of access to lethal means.

In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Psychiatrists implemented the Defeat Depression Campaign in 1992 ( 44 , 45 , 46 ). It lasted five years and had three principal objectives: educate health care professionals, especially general practitioners, to recognize and manage depression; make the public aware of depression and of various treatment options to encourage early care seeking; and reduce discrimination associated with depression. The key message—that depression is a common disease, serious but treatable—was disseminated to the public in a three-week media campaign each year in 1994, 1995, and 1996. More detailed messages were disseminated by use of audio- and videocassettes and books aimed at several population subgroups, and these messages were debated during seminars and conferences. Brochures addressing certain aspects of depression (for example, among elderly persons, among coworkers, or among postnatal women) were translated into several languages and made available at the campaign's Web site.

Evaluations indicated that this program was barely visible to the public; it was estimated that 5% of the public were aware of the campaign in 1995 and 2% in 1997 ( 44 , 45 ). The Defeat Depression Campaign increased population awareness of depression and various treatment options only slightly. For example, from 1991, before the campaign began, to 1997, a year after it ended, the proportion of respondents who recognized that depression is a disease increased by less than 10%. The perception of available treatments also changed little: in both 1991 and 1997 most respondents considered both antidepressants and tranquilizers to be addictive. Finally, suicide rates did not change significantly.

The Royal College of Psychiatristslaunched its next program, Changing Minds, in 1998 ( 47 , 48 , 49 ). Over a five-year period, the program addressed six of the most common mental disorders, including depression, in order to reduce the stigma and discrimination associated with them. The campaign relied on distribution of educational material in various formats for each disorder. They included a book of first-hand accounts by people with mental illness, brochures and books aimed at various target populations, and a scientific report on attitudes and behaviors among health care professionals that maintained discrimination and stigmatization ( 50 ). Several media campaigns were conducted simultaneously. The evaluation of this program indicated a significant reduction of several percentage points in the proportion of people expressing negative attitudes toward individuals with mental illness. Nineteen percent of interviewees in 2003 reported that persons with severe depression were dangerous, compared with 23% in 1998. In addition, 56% reported in 2003 that it was difficult to talk with severely depressed persons, compared with 62% in 1998.

A mental health educational campaign, the Community Awareness Program, was launched in April 1995 in Australia to inform the public about mental illness, including depression, and reduce discrimination toward people with these illnesses ( 51 , 52 , 53 ). The program included a campaign that presented advertisements on television and in movie theaters as well as on a billboard and in other types of displays. The campaign involved two successive phases of exposure, two months apart, and distribution of an information kit for mental health professionals, general practitioners, and schools. It delivered the following key messages: anyone can have a mental illness, mental illness is a disease like any other, help is available for people with mental illnesses, and mental illnesses can be cured. Brochures were edited to address the various mental illnesses targeted in the campaign.

Assessments indicated that awareness of mental illness among persons who were questioned increased: before the campaign 61% reported having seen, heard, or read something about mental health, and after the first and the second waves of the campaign, the proportions were 66% and 70%, respectively. People who were exposed to the campaign were more likely than those who were not to report that they would be willing to engage in social or work relationships with people with mental illness. A slight increase in knowledge of available services was also observed after the campaign. However, to the best of our knowledge, no specific results about depression were published.

In 2001 Australia launched the national "beyondblue" project to increase the population's ability to prevent and respond to depression ( 54 , 55 , 56 ). This program combined various levels of actions and aimed especially to create community awareness and mobilization about depression, reduce discrimination, and improve support of people with mental illness. A media campaign presented the experiences of Australians affected by depression and delivered the following message: depression is a major health problem in Australia that can be recognized by specific signs and symptoms. The presentations also explained how to react to a person with depression and how to find help. People with mental illness participated in the project's design and implementation. The evaluation showed improvements in public knowledge and attitudes about depression (for example, fewer false beliefs), especially in the states where the campaign was most active ( 56 ).

The Like Minds, Like Mine project began in 1997 in New Zealand to change attitudes about and behavior toward people with mental illness, including depression, by reducing negative stereotypes ( 57 , 58 , 59 ). People with mental illness participated in all stages of the program, which combined regional and community action, training and education of professionals and media, and a media campaign (waves of exposure in 2000, 2002, and 2004) with other communication strategies—for example, a Web site and four newsletters a year. The first wave of the media campaign presented accounts by celebrities and "ordinary"people who had had a mental illness. During the second wave, well-known personalities talked about the importance of social support. The last wave challenged some common ideas about people with mental illness and disseminated the slogan "Learn to know people before you judge them." Specific ads were addressed to different communities (Maori, Pacific Islanders, and Pakeha).

In evaluations half of the people questioned reported that they had seen or heard at least one of the campaign's ads after the first wave of exposure, and the proportion was 75% after the second wave. Recall of the principal messages about support and discrimination increased with the number of waves of exposure (from 32% to 50%), as did recall of the availability of help (from 7% to 17%). The results also suggested improvement in knowledge of mental illness and attitudes toward people with mental illness. In particular, awareness of depression increased from 28% to 49% between the first and fourth surveys. The impact was smaller in some ethnic communities, such as the Maori and Pacific Islander communities. An evaluation in which people with mental illness were interviewed found that 85% considered the campaign to have "helped a little or a lot to reduce the stigmatization and discrimination associated with mental illness"( 58 ).

At the end of 2002 Scotland launched a national suicide prevention plan, Choose Life ( 60 ). A key activity was a media campaign against stigmatization, See Me, which was based on accounts of people with mental illness ( 61 , 62 ). This campaign, organized in four waves, included a billboard and display campaign, distribution of educational materials, and creation of a Web site. Evaluations showed that the program increased the general public's awareness of mental health. Seventy-two percent of those questioned in 2004 reported having seen, heard, or read something about mental health during the year, compared with 43% in 2002. Television was the campaign's most effective and visible medium. Moreover, 60% of those questioned believed that the campaign was likely to modify their attitudes toward people with mental illness. Over two years, a significant reduction was noted in reported negative attitudes. For example, the proportion of people who agreed with the following statement fell by 5 percentage points: "If I had a mental illness, I would not want anyone to know," and the proportion who agreed that "people with mental illness are often dangerous" fell by 17 percentage points. A very slight increase in positive attitudes was also found.

Local and community programs

Table 4 presents information on local and community programs. The Defeat Depression Campaign was a four-year program established in 1999 in western Hong Kong to inform Chinese-speaking communities about depression and its prevention and treatment ( 63 , 64 ). After a preliminary study of inhabitants' needs, it distributed educational material, in particular brochures from the U.K. Defeat Depression Campaign that were translated into Chinese. With the help of local media and a Web site, the campaign also organized more than 30 events on the topic of depression, including road shows and exhibitions. In 2001 and 2002 a radio series broadcast 20-minute case studies about depression in several at-risk groups. A training kit was also distributed to professionals, particularly to physicians. The pre-post evaluation study showed a significant improvement in public knowledge about depression; 54% of respondents understood that depression was a mental illness in 1999, compared with 77% in 2002 (p<.01). Moreover, more people reported seeking formal treatment—2.1% in 1999, compared with 9.1% in 2002 (p<.01).

The Compass Strategy program, conducted in the Melbourne, Australia, region from 2001 through 2003, targeted the population aged 12 to 25 years to promote early diagnosis and treatment of mental illness ( 65 ). It was based on the Precede-Proceed health promotion model ( 66 ) and on a detailed study of the epidemiologic, environmental, cultural, and social context in which the program was to be implemented and used a variety of media: a large billboard campaign, distribution of educational material, a Web site, and a telephone information service. The evaluation indicated that in the exposed region, knowledge of suicide risks associated with depression and of the prevalence of mental illness improved, negative attitudes toward help seeking were reduced, perception of treatments and their effectiveness became more positive, the proportion of people who considered themselves depressed increased slightly but significantly, help-seeking behavior increased significantly but not among those who perceived themselves as depressed, and knowledge of resources and recognition of various mental illnesses did not improve.

Local and community programs to reduce suicide rates

Thematic days or weeks organized each year in various countries, such as international suicide day and mental health information week, aim to increase population awareness and mobilize professionals around the issue of suicide—and mental illness more broadly—to reduce stigmatization and promote care seeking. More specifically, Suicide Prevention Week (SPW) is an annual event organized to reduce suicide rates over the long term. Generally, the broad themes are decided upon each year at the national level, and local or community implementation is then organized. As part of SPW in Canada, assessments were conducted locally in 1991 ( 67 ) and in Quebec province from 1999 to 2001 ( 68 , 69 ). Suicide prevention centers prepare and distribute promotional material and organize local media campaigns, training workshops, and seminars. The 1991 evaluation indicated that the number of calls and visits to suicide prevention centers increased, as did hospital admissions for mental illness, but only in the week following SPW. From 1999 to 2001 evaluations in Quebec revealed the poor visibility of SPW: knowledge about suicide crises improved but not negative attitudes toward people who are suicidal. Statements of intent to seek help and the number of calls and visits to suicide prevention centers did not change.

The Nuremberg Alliance Against Depression was launched in 2001 in Germany for two years to improve the identification and management of depression and to reduce suicide rates ( 70 , 71 , 72 ). It combined a public awareness campaign, cooperation with general practitioners, gatekeepers (for example, teachers, priests, and police officers), and support of self-help activities by people with mental illness. The evaluation of the awareness campaign found improved knowledge about depression and its treatment; a significant reduction—approximately 20%—in suicidal behavior (attempted and completed suicides) in Nuremberg compared with Wurzburg, a city that was not exposed to the program; and no significant effect on negative public attitudes about antidepressants ( 70 ). The project was replicated in several regions of Germany and served as a model for the European Alliance Against Depression, a project launched in 16 European regions in 2004 ( 73 ).

Discussion

The studies reviewed above have several limitations in terms of their characterization of context, their program design, and their evaluation methods. Few of the published reports described preliminary "diagnostic" surveys intended to pinpoint the epidemiologic, environmental, social, and cultural context in which the program was to be introduced. Such surveys are essential for determining what has been already done and what is needed by various population subgroups, for designing the programs (objectives, target populations, methods, and means), and for collecting data for pre-post comparisons. Preliminary surveys should document viewpoints of various stakeholders and of people with mental illness.

Few programs appeared to be based on theoretical foundations or to follow a model for their implementation and evaluation. (An exception is the Precede-Proceed model [66].) Models and theories from social sciences and notably health and social psychology—social representations, reasoned action, and planned behavior theories ( 74 , 75 )—as well as health promotion, communication, and social marketing models are examples of theories useful for designing and implementing awareness programs.

Certain programs were very ambitious because they had several objectives (improvement of knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking behavior), were targeted to the entire population, and focused on mental illness—that is, on disorders with various symptoms, origins, and treatments, such as depression, suicidal behavior, anorexia, and schizophrenia. The published material did not always make it clear how depression or suicide were addressed ( 33 , 57 ). Moreover, this heterogeneity and ambition may perhaps explain the lack of effectiveness of certain programs.

Program evaluation

Study design. The evaluations were not all published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Only one evaluation study was a randomized controlled trial (of a gatekeeper training program [40,41]), because public campaigns are collective interventions that cannot be randomly allocated to individuals. Three evaluations were based on cohort studies ( 32 , 33 , 42 ) with pre- and postintervention comparisons; all included a control (unexposed) group, but the studies also had a high rate of loss to follow-up. Most of the remaining 11 evaluation studies were repeated cross-sectional studies, conducted before and after the intervention. Three included a control group ( 51 , 54 , 70 ), but two ( 51 , 54 ) had serious methodological limitations, such as nonrandom sample selection, low response rates, or small sample sizes.

Indicators and instruments. We observed substantial between-study variation in the indicators used to measure the visibility and effects of programs, which was partly but not entirely attributable to variations in objectives. For example, visibility was measured by different variables: having heard of the program, having seen it, or remembering its messages. Evaluation of knowledge about mental illness focused on several items that raise the question of what most adults in the general population should reasonably know about various mental illnesses: prevalence, symptoms, treatments, or types and places of care. Attitudes toward mental illness and people with mental illnesses considered in each study varied substantially. In campaigns aimed at several mental illnesses, specific results about depression or suicide were not always presented, so that it was unclear whether the evaluation included indicators about these problems ( 49 , 51 , 57 ). Instruments used to assess the population's knowledge about and attitudes toward mental illness and people with mental illnesses frequently appeared to be ad hoc instruments and were rarely standardized or validated, although some validated tools exist and have been used, such as the Depression Literacy Questionnaire ( 39 , 76 , 77 ). Substantial variations existed in the timing of posttests.

Indicators of behavior and intended behavior were considered less frequently: six programs used none. For the others, the indicators differed between studies: intention to seek help ( 32 , 34 , 64 , 65 , 68 ), seeking mental health care services or seeing professionals ( 55 , 67 ), and rates of suicide or attempted suicide ( 45 , 71 ). Assessing the impact of campaigns on rates of suicide or attempted suicide is especially difficult, because of the relative rarity of suicide in the overall population and the large population size required to demonstrate an effect ( 78 ).

Limited evaluations. Few studies assessed the persistence of the attitudinal and behavior changes beyond six months. None of the studies estimated the cost-effectiveness of the interventions.

Impact on knowledge, attitudes, and behavior

Despite the limitations described above, this literature review suggests that public awareness and information programs about suicide or depression improve knowledge and awareness of mental illness in the population, at least in the short term. On the other hand, improvement in knowledge of key places to obtain information and professional help was less evident. This review also suggests that with two exceptions, the campaigns contributed to improving public attitudes toward mental illness and its treatment and attitudes toward people with mental illness and therefore contributed to increasing social acceptance of persons with mental illness. Nonetheless, the first campaign in the United Kingdom ( 45 ) and the Nuremberg project ( 70 ) did not affect negative attitudes about medication treatments, which were still perceived to be highly addictive. Moreover, improvements noted in knowledge and changes in attitudes, although significant, were often modest (fewer than 10 percentage points).

On the other hand, the effects of these campaigns on public behavior (intention to seek care, care seeking, and suicidal behavior) are uncertain. Only three programs led to a significant increase in reports of intention to seek professional care ( 34 , 63 , 65 ). The programs that evaluated changes in seeking specialist treatment produced positive results only in the very short term ( 67 ). Two projects included suicide rate trends in their evaluations ( 45 , 71 ), and neither generated a significant reduction in suicide rates. However, the Nuremberg program led to a large and significant reduction in rates of suicidal behavior and attempted suicide ( 71 ).

Some program characteristics appear to be associated with a positive impact. Simultaneous application of several strategies, such as distribution of educational material, a media campaign, and training of gatekeepers and health care professionals, appears more effective in achieving significant results than the distribution of educational material alone. Although implementation of programs at the national level is appealing because of the size of the potentially exposed population, it appears necessary to organize programs at a local level, to target relatively limited and homogeneous populations, and to adapt the messages to them. Similarly, it appears more appropriate to target one or two diseases rather than attempt to make the population aware of mental illness in general, because of the heterogeneity of mental illnesses and their different characteristics and treatment approaches.

Repeated exposure to the campaign also seems to be associated with the best results, because it reinforces the messages. Similarly, it appears to be important to employ several types of exposure (for example, television, print media, and billboards) and to focus on the clarity and specificity of the messages. The involvement of people with mental illness appears useful. By sharing their experiences they can promote a reduction in stigmatization. Nonetheless, media exposure may entail uncontrollable and unpredictable risks for them and for the campaign. Gatekeeper training has the advantage of being applicable on a local or community scale ( 40 , 42 , 71 ) and has yielded some very positive results in the workplace ( 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ).

Conclusions

To heighten public awareness of mental illness, an increasing number of countries are establishing action programs, which sometimes but not always target depression or suicide. The results of this review suggest that these programs improve the general public's knowledge of suicide and depression and contribute at least moderately to better social acceptance of people with depression and other mental illnesses. However, it is difficult to establish whether these programs help to increase care seeking or to reduce suicidal behavior.

Comprehensive evaluation of the impact of these programs presents several difficulties, particularly because of the lack of comparability between programs and between the methods used to evaluate them. Efforts should be made to consolidate international expertise and knowledge and develop guidelines to help design programs and their evaluation. We particularly recommend that guidelines focus on the types of information and data that need to be gathered in order to appropriately assess needs and context before the program is designed; a review of existing theoretical models and the criteria for selecting a model and program objectives; standardized indicators for evaluation of visibility and effects, especially regarding attitudes and behavior; and a review of validated instruments for measuring these indicators or identifying the necessary steps to develop them. We also recommend that research focus on the duration of attitudinal and behavioral changes and on the cost-effectiveness of programs with various characteristics.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This review was supported by the French Southeast Regional Health and Welfare Bureau (DRASS). The authors thank Jo Ann Cahn for translating the manuscript and Xavier Briffault and Enguerrand du Roscoat for their invaluable advice.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Taylor SJ, Kingdom D, Jenkins R: How are nations trying to prevent suicide? An analysis of national suicide prevention strategies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 95:457–463, 1997Google Scholar

2. Beautrais AL: National strategies for the reduction and prevention of suicide. Crisis 26:1–3, 2005Google Scholar

3. Burns JM, Patton GC: Preventive interventions for youth suicide: a risk factor-based approach. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:388–407, 2000Google Scholar

4. Althaus D, Hegerl U: The evaluation of suicide prevention activities: state of the art. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 4:156–165, 2003Google Scholar

5. Guo B, Scott A, Bowker S: Suicide Prevention Strategies: Evidence From Systematic Reviews. Edmonton, Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 2003Google Scholar

6. Gunnell D, Frankel S: Prevention of suicide: aspirations and evidence. British Medical Journal 308:1227–1233, 1994Google Scholar

7. Guo B, Harstall C: For Which Strategies of Suicide Prevention Is There Evidence of Effectiveness? Copenhagen, World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2004Google Scholar

8. Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al: Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 294:2064–2074, 2005Google Scholar

9. Goldney RD: Suicide prevention: a pragmatic review of recent studies. Crisis 26:128–140, 2005Google Scholar

10. Beautrais A: Suicide prevention strategies 2006. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health 5(1), 2006Google Scholar

11. WHO Health Report 2001. Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2001Google Scholar

12. Consensus Statement on Preventive Psychiatry. Geneva, World Psychiatric Association, 2002. Available at www.wpanet.org Google Scholar

13. Lecrubier Y: The influence of comorbidity on the prevalence of suicidal behaviour. European Psychiatry 16:395–399, 2001Google Scholar

14. Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al: Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. British Journal of Psychiatry 192:98–105, 2008Google Scholar

15. Hayward P, Bright J: Stigma and mental illness: a review and critique. Journal of Mental Health 6:435–454, 1997Google Scholar

16. Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, et al: Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:4–7, 2000Google Scholar

17. Byrne P: Psychiatric stigma. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:281–284, 2001Google Scholar

18. Corrigan P, Kerr A, Knudsen L: The stigma of mental illness: explanatory models and methods for change. Applied and Preventive Psychology 11:179–190, 2005Google Scholar

19. Freimuth V: Effectiveness of mass-media health campaigns. Presented at the Second International Symposium on the Effectiveness of Health Promotion, Toronto, May 28–31, 2001. Toronto, Ontario, University of Toronto, Centre for Health Promotion. Available at www.utoronto.ca/chp/Symposium.htm Google Scholar

20. Evans WD: How social marketing works in health care. British Medical Journal 332:1207–1210, 2006Google Scholar

21. Merzel C, D'Afflitti J: Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance, and potential. American Journal of Public Health 93:557–574, 2003Google Scholar

22. Ploeg J, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al: A systematic overview of adolescent suicide prevention programs. Canadian Journal of Public Health 87:319–324, 1996Google Scholar

23. Ploeg J, Ciliska D, Brunton G, et al: The Effectiveness of School-Based Curriculum Suicide Prevention Programs for Adolescents. Dundas, Ontario, Social and Public Health Services Division, Community Support and Research Branch, Effective Public Health Practice Project, 1999Google Scholar

24. Guo B, Harstall C: Efficacy of Suicide Prevention Programs for Children and Youth. Edmonton, Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research, 2002Google Scholar

25. Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, et al: Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: a review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:386–405, 2003Google Scholar

26. Crowley P, Kilroe J, Burke S: Youth Suicide Prevention: An Evidence Briefing. Dublin, Institute of Public Health in Ireland, Health Development Agency, 2004. Available at www.publichealth.ie Google Scholar

27. Julien M, Laverdure J: Scientific recommendation for preventing suicide among young people [in French]. Quebec, Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec, Direction Développement des Individus et des Sociétés, 2004Google Scholar

28. Davis D, O'Brien MA, Freemantle N, et al: Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA 282:867–874, 1999Google Scholar

29. Kroenke K, Taylor-Vaisey A, Dietrich AJ, et al: Interventions to improve provider diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care: a critical review of the literature. Psychosomatics 41:39–52, 2000Google Scholar

30. Hodges B, Inch C, Silver I: Improving the psychiatric knowledge, skills, and attitudes of primary care physicians, 1950–2000: a review. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1579–1586, 2001Google Scholar

31. Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, et al: Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA 289:3145–3151, 2003Google Scholar

32. Barker C, Pistrang N, Shapiro DA, et al: You in Mind: a preventive mental health television series. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 32:281–293, 1993Google Scholar

33. Fonnebo V, Sogaard A: The Norwegian Mental Health Campaign in 1992: part I. population penetration. Health Education Research 10:257–266, 1995Google Scholar

34. Sogaard A, Fonnebo V: Norwegian Mental Health Campaign in 1992: part II: changes in knowledge and attitudes. Health Education Research 10:267–278, 1995Google Scholar

35. Melhum L, Schwebs R: Suicide prevention in the military: recent experiences from the Norwegian armed forces. International Review of the Armed Forces Medical Services 74:71–74, 2001Google Scholar

36. Rozanov VA, Mokhovikov AN, Stiliha R: Successful model of suicide prevention in the Ukraine military environment. Crisis 23:171–177, 2002Google Scholar

37. Knox KL, Litts DA, Talcott GW, et al: Risk of suicide and related adverse outcomes after exposure to a suicide prevention programme in the US Air Force: cohort study. British Medical Journal 327:1376, 2003Google Scholar

38. Mishara B: Evaluation of the Suicide Prevention Program for Police Officers in Montreal [in French]. Montréal, Université du Québec, Centre de Recherche et d'Intervention sur le Suicide et l'Euthanasie (CRISE), 2002Google Scholar

39. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al: Mental health literacy: a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia 166:182–186, 1997Google Scholar

40. Kitchener BA, Jorm AF: Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry 2:10, 2002Google Scholar

41. Jorm AF, Kitchener BA, Mugford SK: Experiences in applying skills learned in a mental health first aid training course: a qualitative study of participants' stories. BMC Psychiatry 5:43, 2005Google Scholar

42. Sundram S, Cole N, McGuiness M, et al: Report on the Depression Awareness Research Project. Parkville, Victoria, Mental Health Research Institute of Victoria, 2004Google Scholar

43. Rutter A, McGuiness M, Sundram S, et al: Satisfying competing stakeholder needs in a Depression Awareness Program. Evaluation Journal of Australasia 5(1):25–32, 2005Google Scholar

44. Priest RG, Vize C, Roberts A, et al: Lay people's attitudes to treatment of depression: results of opinion poll for Defeat Depression Campaign just before its launch. British Medical Journal 313:858–859, 1996Google Scholar

45. Paykel ES, Hart D, Priest RG: Changes in public attitudes to depression during the Defeat Depression Campaign. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:519–522, 1998Google Scholar

46. Rix S, Paykel ES, Lelliott P, et al: Impact of a national campaign on GP education: an evaluation of the Defeat Depression Campaign. British Journal of General Practice 49:99–102, 1999Google Scholar

47. Crisp AH: Changing Minds: every family in the land: a campaign update. Psychiatric Bulletin of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. 25:444–446, 2001Google Scholar

48. Office of National Statistics: Stigmatisation of People With Mental Illness: Report of the Research Carried out in July 1998 and July 2003. London, Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2003Google Scholar

49. Crisp A, Gelder M, Goddard E, et al: Stigmatization of people with mental illnesses: a follow-up study within the Changing Minds campaign of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. World Psychiatry 4:106–113, 2005Google Scholar

50. Mental Illness: Stigmatisation and Discrimination Within the Medical Profession. Council Report CR91. London, Royal College of Psychiatrists, Feb 2001Google Scholar

51. Community Attitudes Toward People With Mental Illness: Advertising Tracking, Wave 2. Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Human Services and Health, Public Affairs and International Branch, 1996Google Scholar

52. Evans Research: Report on the Review of Mental Health Information Brochures Produced Under the Community Awareness Program (CAP). Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Mental Health Branch, 1999Google Scholar

53. Rosen A, Walter G, Casey D, et al: Combating psychiatric stigma: an overview of contemporary initiatives. Australasian Psychiatry 8:19–26, 2000Google Scholar

54. Hickie I: Can we reduce the burden of depression? The Australian experience with beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Australasian Psychiatry 12(suppl):S38–S46, 2004Google Scholar

55. Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM: Changes in depression awareness and attitudes in Australia: the impact of beyondblue: the national depression initiative. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40:42–46, 2006Google Scholar

56. Highet NJ, Luscombe GM, Davenport TA, et al: Positive relationships between public awareness activity and recognition of the impacts of depression in Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40:55–58, 2006Google Scholar

57. Akroyd S, Wyllie A: Impacts of a National Media Campaign to Counter Stigma and Discrimination Associated With Mental Illness: Survey 4. Research report for the Ministry of Health. Auckland, New Zealand, Phoenix Research, Dec 2002Google Scholar

58. Akroyd S, Wyllie A: People With Experience of Mental Illness: Perceptions of "Like Minds" Project. Research Report for the Ministry of Health. Auckland, New Zealand, Phoenix Research, Mar 2003Google Scholar

59. Vaughan G, Hansen C: "Like Minds: Like Mine": a New Zealand project to counter the stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness. Australasian Psychiatry 12:113–117, 2004Google Scholar

60. Choose Life: A National Strategy and Action Plan to Prevent Suicide in Scotland. Edinburgh, Scottish Executive, 2002Google Scholar

61. Glendinning R, Buchanan T, Rose N: Well? What Do You Think? A National Scottish Survey of Public Attitudes to Mental Health, Well Being and Mental Health Problems. Edinburgh, Scottish Executive, 2002Google Scholar

62. Braunholtz S, Davidson S, King S: Well? What Do You Think? The Second National Scottish Survey of Public Attitudes to Mental Health, Well Being and Mental Health Problems. Edinburgh, Scottish Executive, 2004Google Scholar

63. Institute of Mental Health: Community Survey on the Public Awareness of Depression in New Territories West District of Hong Kong. Hong Kong, Lingnan University, 1999Google Scholar

64. Institute of Mental Health: Post-Project Community Survey on the Public Awareness of Depression in New Territories West District of Hong Kong. Hong Kong, Lingnan University, 2002Google Scholar

65. Wright A, McGorry PD, Harris MG, et al: Development and evaluation of a youth mental health community awareness campaign: the Compass Strategy. BMC Public Health 6:215, 2006Google Scholar

66. Green L, Kreuter M: CDC's Planned Approach to Community Health as an Application of PRECEDE and an inspiration for PROCEED. Journal of Health Education 23:140–147, 1992Google Scholar

67. Dyck R: Suicidal awareness weeks: the outcomes; in Proceedings of the 16th Congress of the International Association for Suicide Prevention. Regensburg, Germany, International Association for Suicide Prevention, 1993Google Scholar

68. Daigle M, Beausoleil B, Brisoux J, et al: Suicide Prevention Week: Evaluation Report [in French]. Trois Rivières, Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Québec, 2002Google Scholar

69. Daigle M, Beausoleil L, Brisoux J, et al: Reaching suicidal people with media campaigns: new challenges for a new century. Crisis 27:172–180, 2006Google Scholar

70. Hegerl U, Althaus D, Stefanek J: Public attitudes towards treatment of depression: effects of an information campaign. Pharmacopsychiatry 36:288–291, 2003Google Scholar

71. Lehfeld H, Althaus DA, Hegerl U, et al: Suicide attempts: results and experiences from the German Competency Network on Depression. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine 26:137–143, 2004Google Scholar

72. Hegerl U, Althaus D, Schmidtke A, et al: The alliance against depression: 2-year evaluation of a community-based intervention to reduce suicidality. Psychological Medicine 36:1225–1233, 2006Google Scholar

73. Hegerl U, Wittmann M, Arensman E, et al: The European Alliance Against Depression (EAAD): a multifaceted, community-based action programme against depression and suicidality. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 9:51–58, 2008Google Scholar

74. Fishbein M, Ajzen I: Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Reading, Mass, Addison Wesley, 1975Google Scholar

75. Fishbein M, Ajzen I: The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50:179–211, 1991Google Scholar

76. Jorm A: Mental health literacy: public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:396–401, 2000Google Scholar

77. Jorm AF, Christensen H., Griffiths, KM: The public's ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about treatment: changes in Australia over 8 years. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40:36–41, 2006Google Scholar

78. Jenkins R: Making psychiatric epidemiology useful: the contribution of epidemiology to government policy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 103:2–14, 2001Google Scholar