Low Socioeconomic Status and Mental Health Care Use Among Respondents With Anxiety and Depression in the NCS-R

A number of studies have shown that low socioeconomic status is associated with premature mortality and poor physical health ( 1 , 2 ). Studies have also shown that low socioeconomic status is related to an increased point prevalence of psychological distress ( 3 ) and depression ( 4 ) and to a more chronic course of depression ( 4 , 5 ). Because some ( 6 , 7 ) but not all ( 8 , 9 ) studies have linked poor general medical outcomes among patients of low socioeconomic status to lower quality of general medical care, it is plausible that some of the association between low socioeconomic status and poorer mental health is the result of disparities in the extent and quality of treatment for mental disorders obtained by socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals compared with those without such disadvantage.

Consistent with this notion, results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) indicated that unmet need for treatment among respondents who had a mental disorder in the past 12 months was greater among those with low incomes than among other respondents ( 10 ). Furthermore, among NCS-R respondents with lifetime mental disorders, less education was related to delays in making initial treatment contact ( 11 ). However, not all studies have shown a strong and definitive relationship between low socioeconomic status and lower probability of receiving mental health care ( 12 , 13 ). Finally, although one study showed that the quality of care among patients in treatment for depression and anxiety disorders was poorer among those with less education ( 14 ), other analyses have not found evidence that quality of care among patients in treatment was significantly related to any measure of socioeconomic status ( 10 , 15 ).

The studies described above varied in the types of mental illnesses that were included. Many analyses of the NCS-R data, for example, combined all mental disorders and did not investigate the possibility that the association of socioeconomic status with treatment might vary by type of disorder. Previous studies have also varied in the treatment sectors that they considered (for example, specialty, general medical, human services, and self-help) and in the dimensions of socioeconomic status that they included (for example, education and income), and few studies have included multiple measures of socioeconomic status.

The study reported here focused on anxiety and mood disorders, because they are the most common mental disorders in the United States ( 16 ) and they are also the mental disorders for which evidence-based treatments have been most extensively investigated. The purpose of the study was to use NCS-R data to examine the associations of socioeconomic status with treatment for anxiety and mood disorders in the sectors that are able to deliver evidence-based treatments—that is, the specialty mental health sector and the general medical sector. We examined receipt of any treatment, and among those who received treatment, we examined receipt of treatment that was at least minimally adequate according to published evidence-based treatment guidelines. Unlike previous studies, this study assessed socioeconomic status in a multidimensional manner, using measures not only of education and income but also of assets. The analyses reported here controlled for race-ethnicity to ensure that associations involving socioeconomic status were not confounded by race-ethnicity, because previous studies have shown that persons in ethnoracial minority groups are more likely to receive lower-quality mental health care for depression and anxiety ( 14 , 15 ).

Methods

Sample

The NCS-R was a nationally representative household survey of respondents aged 18 years and older in the coterminous United States ( 16 , 17 ). Face-to-face interviews were carried out with 9,282 respondents between February 5, 2001, and April 7, 2003. Respondents were paid $50 for participation. Verbal informed consent was obtained before the interviews were conducted. Consent was verbal rather than written to be consistent with procedures used in the baseline NCS ( 18 ). The NCS-R recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the human subjects committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. The survey response rate was 70.9%.

The interview was administered in two parts. Part I included a core diagnostic assessment that was administered to all 9,282 respondents. Part II assessed risk factors and their correlates, service use, and additional disorders. Part II was administered to all part I respondents with a lifetime mental disorder plus a probability subsample of other part I respondents, for a total sample of 5,692 in part II. A more detailed description of field methods and procedures is presented elsewhere ( 19 ).

In the study reported here the respondents were the 1,772 part II respondents who met criteria either for a 12-month nonbipolar mood disorder or a 12-month anxiety disorder The part II sample was used rather than the part I sample because use of services was assessed in part II.

Measures

Diagnostic assessment of 12-month mental disorders. DSM-IV diagnoses were based on version 3.0 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) ( 20 ), a fully structured, lay-administered diagnostic interview that generates ICD-10 and DSM-IV diagnoses. This study focused on 12-month DSM-IV diagnoses of mood disorders (major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder) and anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and separation anxiety disorder). Blind clinical reappraisals with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) showed generally good concordance between CIDI and SCID lifetime diagnoses of anxiety and mood disorders ( 21 ).

Twelve-month use of mental health services. All part II respondents were asked whether they ever received treatment for "problems with your emotions or nerves or your use of alcohol or drugs." A list of types of treatment providers was presented in a respondent booklet to provide a visual recall aid. The list included psychiatrists; general and specialist physicians, including physician's assistants and nurse practitioners; and mental health professionals, such as social workers, counselors, and therapists. Treatment received from the various types of professionals and for the settings in which treatment was received were assessed separately. Reports of 12-month service use were classified into mental health specialty (psychiatrist or other mental health professional) and general medical (nonpsychiatrist physician, physician's assistant, or nurse-practitioner).

Minimally adequate treatment. Minimally adequate treatment was defined by use of an approach described previously ( 10 ) and according to evidence-based guidelines ( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ). Treatment was defined as at least minimally adequate if the patient received either two months of an appropriate medication (antidepressants for depression and either antidepressants or anxiolytics for anxiety disorders) plus at least four visits either to a psychiatrist or to the general medical sector for medication monitoring or if the patient received at least eight psychotherapy sessions with any health care professional lasting an average of at least 30 minutes each. The rationale for these criteria has been articulated elsewhere ( 10 ). Treatment adequacy was defined separately for each 12-month disorder. Among patients with comorbid disorders, receipt of adequate treatment for at least one disorder was considered adequate treatment.

Socioeconomic status and sociodemographic variables. Indicators of socioeconomic status included completed years of education, family income, and assets. Family income was assessed relative to the federal poverty line, which was categorized as low income (less than 1.5 times the poverty line), low-average income (1.5–3.0 times the poverty line), high-average income (three to six times the poverty line), and high income (greater than six times the poverty line). Nonincome assets were categorized as negative assets (debt) or no assets, less than $10,000 in assets, and $10,000 or more in assets. If a respondent had nonincome assets but was unsure of the amount, the asset category "amount unknown" was used. For income and assets, the cutoff points were selected to generate categories with roughly equal numbers of respondents.

We also included the following sociodemographic variables as controls: respondent age at interview, gender, race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other), marital status (married or cohabiting, previously married, and never married), urbanicity (based on the 2000 census definitions of counties in major metropolitan areas, nonmetropolitan urban areas, and rural areas), and health insurance coverage (yes or no). These variables were included as controls because they are correlates of socioeconomic status and are also related to health care utilization. However, these variables are not mediators of the potential effects of socioeconomic status on treatment utilization, and thus they are not pathways through which any socioeconomic effects would occur.

Analysis procedures

The part II NCS-R data were weighted to adjust for differences in probabilities of selection, differential nonresponse, residual differences between the sample and the U.S. population on a wide range of sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables, and oversampling in the part II sample. Data analysis was carried out using the Taylor series linearization method, implemented in the SUDAAN software system, to adjust for the weighting and clustering of the data. Frequencies, means, and standard deviations were calculated first to generate basic descriptive data about respondents with anxiety and mood disorders. Bivariate logistic regression analyses were then conducted to evaluate the predictive effect of each socioeconomic and sociodemographic variable for each of the three types of treatment. Subsequent logistic models were estimated that included all predictors at once. Logistic regression coefficients and their standard errors were exponentiated for ease of interpretation and are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical significance was consistently assessed with two-sided tests at the .05 level.

Results

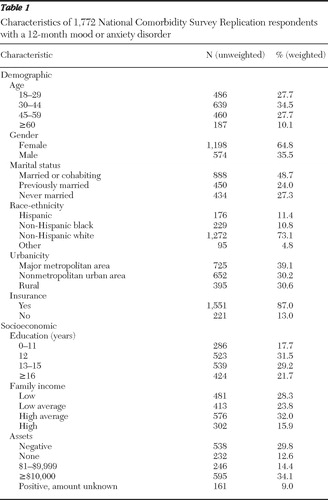

Data on the characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1 and indicate wide variation in three socioeconomic variables of interest (education, income, and assets). Of the 1,772 respondents with mood or anxiety disorders, 424 (23.8%) received treatment in the general medical sector, 383 (20.8%) in the mental health specialty sector, and 662 (36.6%) in either sector. Of the 1,469 patients who received treatment, the treatment was minimally adequate for 51 patients (12.7%) in the medical sector, 183 (46.4%) in the mental health specialty sector, and 217 (32.1%) who received treatment in either sector. (All percentages are weighted.)

|

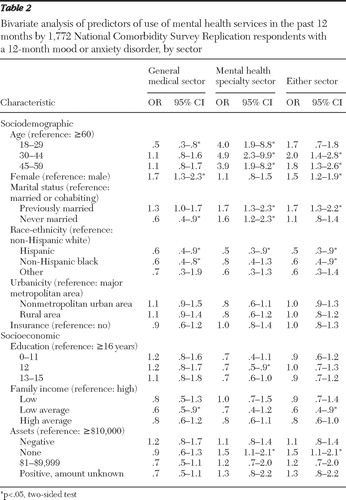

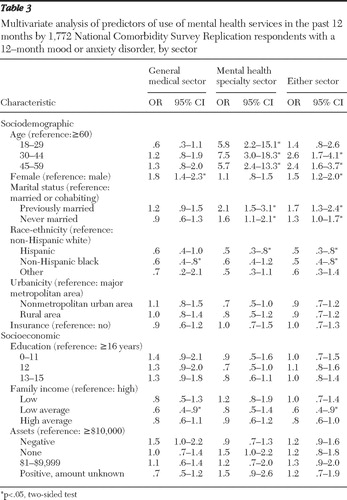

Tables 2 and 3 show bivariate and multivariate relationships between socioeconomic and sociodemographic measures and use of mental health services in the general medical sector, the mental health specialty sector, and overall (either sector). Age, gender, marital status, and race-ethnicity were strong and fairly consistent predictors of mental health services use, with some modest variations by sector. In contrast, socioeconomic characteristics were limited predictors of mental health services use. In both bivariate and multivariate analyses, respondents with low-average income were less likely to use services overall and in the general medical sector. In bivariate analyses, respondents with a 12th-grade education were less likely to use services in the mental health specialty sector, and respondents with no assets were more likely to use mental health services in the specialty sector or in either sector, but these associations were not significant in the multivariate analysis.

|

|

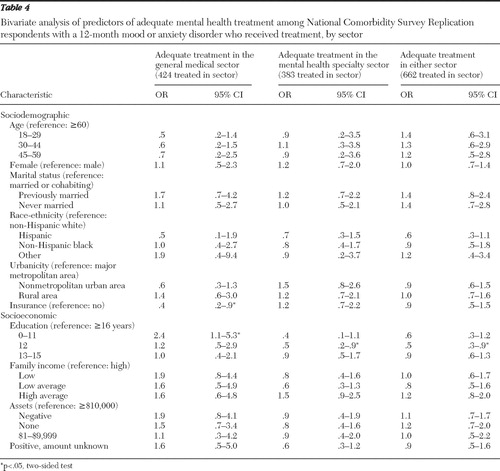

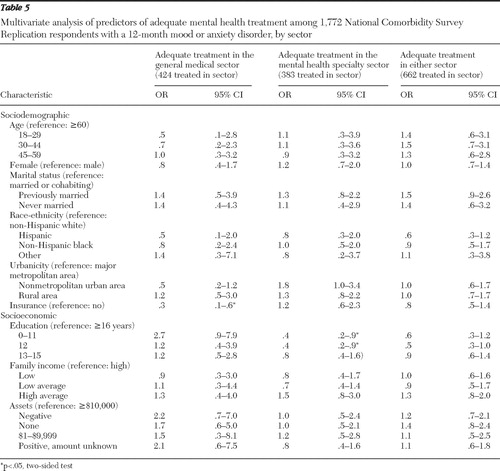

Predictors of receipt of adequate mental health care were assessed in bivariate ( Table 4 ) and multivariate ( Table 5 ) analyses. Only one significant predictor was found in the final multivariate analysis: having less than a 12th-grade education predicted less adequate care in the specialty mental health setting.

|

|

Analyses were also conducted to test for interactions between race-ethnicity and the three socioeconomic status variables with respect to both receipt of any mental health care in any sector and receipt of adequate care. None of the interactions were statistically significant.

Discussion

This study was limited by the exclusion of homeless people and institutionalized patients and by the possibility of systematic survey nonresponse or of nonreporting related to depression and anxiety among respondents. In addition, diagnoses and reports of treatment were based on lay interviews rather than on clinician-administered interviews and treatment records; however, as noted above, a clinical reappraisal study documented good concordance between the CIDI diagnoses and independent clinical diagnoses on the basis of blinded reinterviews. Also, the definitions of minimally adequate treatment, though based on several expert guidelines, have not been extensively validated.

Within the context of these limitations, the findings are of interest given the wide range of the socioeconomic status measures, the large sample, and the fact that the sample was nationally representative. Furthermore, our findings of an association between mental health service use and sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, and marital status replicate results of previous studies that used data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study ( 13 ), the original NCS ( 26 ), and the National Survey of American Life ( 27 ),which suggests that our approach has validity. In contrast to previous findings in regard to socioeconomic status and general medical illness, the results reported here suggest that socioeconomic status does not play a major role in determining aspects of the treatment of the mental disorders that were considered in this report. This finding is consistent with previous studies that found either weak or nonsignificant associations between mental health service use and both income and education in heterogeneous groups of psychiatric patients (that is, the sample included patients with diagnoses in addition to depression and anxiety) ( 12 , 13 ). It is, of course, possible that socioeconomic status is related to other aspects of treatment, such as the type of setting in which treatment is received (for example, community mental health center, health clinic, and private physician's office), the types of medications received (for example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants), the quality of the psychotherapies received, and other aspects of treatment quality that were not tapped by our rough measure of minimally adequate treatment.

Patients with anxiety and depression who were from minority groups, specifically Hispanic and non-Hispanic black respondents, were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to receive mental health services, which is consistent with previous findings ( 27 , 28 ). Our finding suggests that the poorer outcomes of patients with depression and anxiety who come from ethnoracial minority backgrounds may be partly related to less frequent receipt of any treatment. In contrast, the poorer outcomes of patients with depression and anxiety who had socioeconomic disadvantages (in education, income, and assets) appear not to be attributable to less frequent receipt of any treatment or to their treatment's being below the minimal standard of adequacy defined here. It remains possible, however, that socioeconomic status is related to the quality of treatment in the subsample of patients who received minimally adequate treatment. We have no way of evaluating this possibility with the available data.

The single statistically significant finding in regard to socioeconomic status was that patients with low-average incomes received less care overall and in the general medical sector. A similar curvilinear relationship between income and mental health service use was observed in a study of children's use of mental health care ( 29 ) and in a study examining need-adjusted costs of general medical care ( 30 ), but the relationships were at the trend level and not significant. Our finding may reflect the fact that respondents with the lowest incomes are likely to be eligible for public health insurance, whereas those with low-average incomes may represent the working poor or recently unemployed individuals without insurance. However, the presence or absence of insurance per se was unrelated to receipt of care.

The absence of predictors of receipt of adequate mental health care is noteworthy and may reflect the relatively small subgroups in the sample and limited analytic power. Patients with the least education were less likely to receive adequate mental health care in the specialty mental health setting. Some characteristics of this setting or context may make less educated patients more vulnerable to not having their care optimized.

Finally, we performed multiple additional analyses to confirm that collinearity did not play a role in obscuring relationships between any of the three specific socioeconomic measures and receipt of any mental health care or receipt of adequate care. All analyses yielded the same substantive results.

Conclusions

This study found minimal evidence of the importance of socioeconomic factors in determining receipt of treatment for depression or anxiety or receipt of minimally adequate treatment for these disorders among persons who received care. These findings suggest that the poorer outcomes of individuals of low socioeconomic status who have depression or anxiety might be attributable to differences in the quality of care beyond the minimally adequate level measured here or differences in factors unrelated to the quality of care, such as the presence of chronic stress, which may partly counteract the effects of treatment. However, we should emphasize that the survey was conducted earlier in this decade, when the socioeconomic environment was dramatically different from the current environment of economic crisis. In previous crises, such as Hurricane Katrina ( 31 , 32 ) or the 1997 financial meltdown in Korea of the International Monetary Fund ( 33 , 34 ), individuals at or near poverty levels experienced the greatest reductions in needed care and the worst mental health outcomes, including suicide ( 34 ). Thus the current crisis may necessitate new and more targeted therapeutic and preventive interventions to avoid poor allocation of resources and disparities in mental health treatment and outcomes along socioeconomic status lines.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Kaiser Permanente, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly and Company and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has received research support for epidemiological studies from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis.

The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AJ, et al: Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. New England Journal of Medicine 358:2468–2481, 2008Google Scholar

2. Marmot M: Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 365:1099–1104, 2005Google Scholar

3. Kessler R, Neighbors H: A new perspective on the relationships among race, social class and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 27:107–115, 1986Google Scholar

4. Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, et al: Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology 157:98–112, 2003Google Scholar

5. Lorant V, Croux C, Weich S, et al: Depression and socio-economic risk factors: 7-year longitudinal population study. British Journal of Psychiatry 190:293–298, 2007Google Scholar

6. Byers TE, Wolf HJ, Bauer KR, et al: The impact of socioeconomic status on survival after cancer in the United States: findings from the National Program of Cancer Registries Patterns of Care Study. Cancer 113:582–591, 2008Google Scholar

7. Jacobi CE, Mol GD, Boshuizen HC, et al: Impact of socioeconomic status on the course of rheumatoid arthritis and on related use of health care services. Arthritis and Rheumatism 49:567–573, 2003Google Scholar

8. Rathore SS, Masoudi FA, Wang Y, et al: Socioeconomic status, treatment, and outcomes among elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the National Heart Failure Project. American Heart Journal 152:371–378, 2006Google Scholar

9. Bernheim SM, Spertus JA, Reid KJ, et al: Socioeconomic disparities in outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. American Heart Journal 153:313–319, 2007Google Scholar

10. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

11. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al: Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:603–613, 2005Google Scholar

12. Alegria M, Bijl RV, Lin E, et al: Income differences in persons seeking outpatient treatment for mental disorders: a comparison of the United States with Ontario and the Netherlands. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:383–391, 2000Google Scholar

13. Leaf PJ, Livingston MM, Tischler GL, et al: Contact with health professionals for the treatment of psychiatric and emotional problems. Medical Care 23:1322–1337, 1985Google Scholar

14. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61, 2001Google Scholar

15. Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC: Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:284–292, 2000Google Scholar

16. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593–602, 2005Google Scholar

17. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, et al: The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:69–92, 2004Google Scholar

18. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Google Scholar

19. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, et al: The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:69–92, 2004Google Scholar

20. Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:93–121, 2004Google Scholar

21. Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, et al: Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 15:167–180, 2006Google Scholar

22. Katon W, von Korff M, Lin EH, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026–1031, 1995Google Scholar

23. Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB, et al: A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication for primary care panic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:290–298, 2005Google Scholar

24. Foa EB, Davidson JRT, Frances A: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 16):1–76, 1999Google Scholar

25. Stein MB: Anxiety disorders: somatic treatment; in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Edited by Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 2005Google Scholar

26. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: Mental health care use, morbidity, and socioeconomic status in the United States and Ontario. Inquiry 34:38–49, 1997Google Scholar

27. Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al: Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:485–494, 2007Google Scholar

28. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

29. Cohen P, Hesselbart CS: Demographic factors in the use of children's mental health services. American Journal of Public Health 83:49–52, 1993Google Scholar

30. Chen AY, Escarce JJ: Quantifying income-related inequality in healthcare delivery in the United States. Medical Care 42:38–47, 2004Google Scholar

31. Wang PS, Gruber MJ, Powers RE, et al: Mental health service use among hurricane Katrina survivors in the eight months after the disaster. Psychiatric Services 58:1403–1411, 2007Google Scholar

32. Wang PS, Gruber MJ, Powers RE, et al: Disruption of existing mental health treatments and failure to initiate new treatment after Hurricane Katrina. American Journal of Psychiatry 165:34–41, 2008Google Scholar

33. Khang YH, Lynch JW, Kaplan GA: Impact of economic crisis on cause-specific mortality in South Korea. International Journal of Epidemiology 34:1291–1301, 2005Google Scholar

34. Kim H, Song YJ, Yi JJ, et al: Changes in mortality after the recent economic crisis in South Korea. Annals of Epidemiology 14:442–446, 2004Google Scholar