Part D and Dually Eligible Patients With Mental Illness: Medication Access Problems and Use of Intensive Services

Approximately one-third (34%) of individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid benefits have a mental disorder. These individuals rely on pharmacotherapy as a key element of mental health treatment ( 1 ). Traditionally, "dual-eligibles" received coverage for prescription drugs through the Medicaid program. Under the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003, drug coverage for this population was shifted from Medicaid to the new Medicare Part D program, and all dually eligible people were randomly assigned to a private Part D plan. Although there have been general concerns about the impact of this change on the dually eligible population, there has been particular concern about how Part D enrollment might affect access to needed psychiatric medications and thus a desire to monitor the consequences of any disruption to pharmacotherapies that might result in negative clinical outcomes ( 2 ).

To examine the occurrence of medication access problems resulting from the transition to Part D for dually eligible beneficiaries, we used psychiatrist reports of their dually eligible patients' post-Part D experiences. We compared psychiatric emergency department use and use of inpatient care among patients who experienced or did not experience a medication access problem after Part D implementation. We hypothesized that compared with individuals who did not experience an access problem, individuals who did would be more likely to receive emergency or inpatient psychiatric care.

Dually eligible beneficiaries are randomly assigned to a Part D plan with a premium at or below the annual regional benchmark set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) (hereafter, "benchmark plan"). In 2006 there were a total of 409 benchmark plans across the United States ( 3 ). In most states, there were at least ten benchmark plans, although that number has decreased in many regions ( 3 ). For example, as of 2009, six states have five or fewer benchmark plans, and Nevada has only one ( 3 ).

Dually eligible beneficiaries are permitted to switch monthly to another benchmark plan in their region, and several states provide substantial assistance to help people switch to plans that may be a better match for their medication needs ( 4 ). An estimated 11% of noninstitutionalized persons with dual eligibility switched plans in 2006 ( 5 ). If a plan's annual premium bid for the coming year exceeds the new benchmark set by CMS, dually eligible beneficiaries enrolled in the plan are reassigned to another benchmark plan.

Under Part D, dually eligible beneficiaries pay no premiums and only nominal copayments for medications. In 2006 full-benefit dual-eligibles paid $1.00–$2.00 for generic medications and $3.00–$5.00 for brand-name medications, depending on their income. Problems with charging patients incorrect cost-sharing amounts were, however, documented in the program's initial implementation ( 6 ). Although Medicaid regulations stipulate that beneficiaries unable to pay copayments required by their state Medicaid program cannot be denied their prescription medications, there is no such regulation under Part D.

Dually eligible beneficiaries are also subject to the formulary and utilization management procedures of the plan in which they are enrolled. Part D plans are required to cover only two medications in each drug class, but antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants were given special protections under the regulations implemented by CMS. For these classes, plans must cover "all or substantially all drugs"—meaning that they must cover at least one, but not all, formulations of each molecule in the class. For example, plans must cover branded Paxil, generic paroxetine, or branded Paxil-CR but are not required to cover all three formulations of paroxetine. However, recent legislation codifying this requirement allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services to specify exceptions that allow Part D plans to exclude a drug in the protected classes from its formulary ( 7 ).

Even though plans are required to include at least one formulation of every drug, plans can use various management tools to control utilization of these drugs. For example, before granting coverage a plan can require an enrollee to obtain prior authorization. Alternatively, some plans require enrollees to try one or more less expensive medications and document a poor response to these drugs before they are granted coverage of a more expensive medication (such rules are known as step therapy or "fail first"). Beneficiaries using established therapies are now exempt from utilization management requirements for medications in these classes, although this policy was not in place when the program was implemented in 2006 ( 8 ). Huskamp and colleagues ( 9 ) found that certain product formulations in these classes were not covered by a number of plans that served dually eligible beneficiaries in 2006, and use of prior authorization was common for a minority of plans. Donohue and colleagues ( 2 ) documented that utilization management requirements for second-generation antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants have increased since 2006.

Many Medicaid programs use management tools similar to those used by Part D plans (such as prior authorization and step therapy) for some medications, and thus the use of certain utilization management methods may not be new to dually eligible beneficiaries. However, even if the rules of a Part D plan are as restrictive as those used under a state Medicaid program, these beneficiaries may be required to switch to a different set of rules than had applied to them in the past. Thus some patients whose condition was stable on a particular medication may have found that the medication was not covered by their new Part D plan in 2006, or perhaps the plan required the enrollee to obtain prior authorization or undergo step therapy before securing coverage. Some enrollees also may have had difficulty paying the copayments required under Part D.

A transition policy required plans to provide a transition supply of medications during the first 90 days of enrollment, which may have reduced medication access issues during the first few months of implementation. However, despite the transition policy, West and colleagues ( 10 ) documented that a large proportion of dually eligible patients experienced problems in the first four months of 2006.

Methods

Data

Observational, clinician-reported surveys tracked patients' experiences during the first 12 months of the implementation of Medicare Part D. Data collection consisted of three cross-sectional assessments: January–April 2006, May–August 2006, and September–December 2006. The target population consisted of all practicing psychiatrists in the United States with a deliverable address who treated dually eligible patients. To allow the maximum time for a patient to have experienced a medication access issue, we used data from only the third cycle of data collection (September–December 2006).

A total of 5,833 psychiatrists were randomly selected from the American Medical Association's Physicians Masterfile of U.S. psychiatrists (N=55,000). After excluding psychiatrists not currently practicing and those with undeliverable addresses, responses were obtained from 66% of the sample (N=3,361) during the first data collection cycle. Of these respondents, 35% met the study eligibility criteria of treating dually eligible patients during their last typical work week and participated in this study, providing clinically detailed data on 1,193 systematically selected patients. For the third data collection cycle (September–December 2006), the 1,189 psychiatrists who participated in the first cycle and 1,600 new psychiatrists randomly selected from the Physician Masterfile were sampled. Responses were obtained from 68% of previous participants (N=803) and 67% of the new sample (N=914). Of those who responded, 56% met the study eligibility criteria, providing data on 986 systematically selected patients.

For this analysis, we excluded 31 nursing home residents, five children under 18, and eight individuals whose only diagnosis was either substance abuse or dependence, mental retardation, mood disorder not otherwise specified, or a non-mental health condition. Thirty-four observations were dropped because of missing data on age or gender. Our final sample size was 908.

Each psychiatrist was randomly assigned one of 21 start days and times to report on the next dually eligible patient treated during the psychiatrist's last typical work week. For each patient included in the study for whom the psychiatrist reported, we obtained data on the patient's sociodemographic characteristics, treatment setting, diagnosis, and clinical characteristics and whether the patient experienced specific medication access problems (no patient-identifying information was obtained, however). We also obtained information on emergency department visits related to the patient's psychiatric illness and psychiatric hospitalizations since January 1, 2006. The average patient in the third data collection sample had 42.1 weeks (95% confidence interval=41.8–42.4) in which to accrue a medication access problem. Of the 908 patients in our sample, 37 had a psychiatrist who reported on the experience of more than one patient (17 psychiatrists reported for two patients and one psychiatrist reported for three patients). All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education.

Analytical approach

We first identified a subgroup of patients who experienced a problem accessing a psychopharmacologic medication after Part D implementation, as reported by their psychiatrist. Psychiatrists were asked whether their patients had experienced the following since January 1, 2006: first, being unable to access clinically indicated medication refills or new prescriptions because the medications were not covered or approved; second, being stable on clinically desired or indicated medication but being switched to a different medication because clinically preferred medication refills were not covered or approved; or third, having problems accessing medications because of inability to pay copayments. If the psychiatrist affirmed any one of these problems, we considered the patient to have experienced a medication access problem. Of our final sample of 908, a total of 400 patients reportedly experienced a medication access problem according to our criteria.

We used propensity score matching, a method of adjusting for observed characteristics of patients nonrandomly assigned to differing interventions ( 11 ), to create pairs who appeared similar in terms of observed characteristics. Each pair of patients included a dually eligible beneficiary who had experienced a problem accessing medications and a similar individual who had not. We performed a 1:1 matched analysis on the basis of the estimated propensity score of each patient. The propensity score model included the following variables: patient sex, patient age group (40 and under, 41–64, or 65 and over), race or ethnicity (white or nonwhite), diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder versus no such diagnosis, and region (Midwest, South, West, and Northeast).

After creating a matched sample of individuals who did and individuals who did not experience a medication access problem, we estimated two types of multivariate models: logistic regression models of the likelihood of having any emergency department visits and any hospitalization days for a psychiatric illness since January 1, 2006, and linear regression models of the number of emergency department visits conditional on having at least one emergency visit and the number of hospitalization days conditional on having at least one psychiatric hospitalization since January 1, 2006. We included as covariates the same variables used in the propensity score matching model to correct for any specification errors in the propensity score models ( 12 ). We also included variables indicating the severity of each patient's symptoms. Physicians were asked to rate the severity of six symptoms (depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, psychotic symptoms, manic symptoms, alcohol or other substance use symptoms, or sleeping problems) as severe, moderate, mild, none, or "don't know." All models included six dummy variables (one for each symptom) indicating whether the psychiatrist reported that the patient experienced a severe form of the symptom. In addition, the regression models included a variable indicating whether the patient's psychiatrist had reported on more than one patient.

We replicated the propensity score matching 300 times in order to obtain more stable estimates of the parameters. On average, we matched 97% of individuals who experienced an access problem with a similar individual who had not. For each of the 300 sets of matched pairs, we estimated the two multivariate models. We present mean results across the 300 replications.

Results

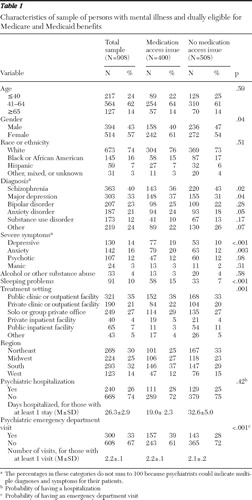

The dually eligible patients in our sample were disproportionately female (57%) and 41–64 years of age (62%) ( Table 1 ). Almost three-quarters (74%) were white, and 16% were black or African American, 7% were Hispanic, and 3% were classified as being of other race or ethnicity. Almost two-thirds (63%) had a diagnosis of either schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

|

Among dually eligible patients in our sample, 318 (35%) were unable to access clinically indicated refills or new prescriptions because the drugs were not covered or approved, 170 (19%) were stable on a clinically desired or indicated medication but switched to a different drug because refills were not covered or approved, and 200 (22%) had problems accessing medications because of copayments. As noted above, a total of 400 patients (44%) experienced one or more of these problems. Compared with patients who did not experience a problem accessing medications, those who experienced a medication access problem were more likely to be women; less likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia; more likely to have a diagnosis of major depression or anxiety; and more likely to have severe depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, or sleeping problems ( Table 1 ).

We found that the mean odds ratio (OR) of having any emergency department visits was higher for those who experienced a medication access problem than for similar individuals who did not (OR=1.75, mean p=.003) ( Table 2 ). The mean predicted probability of visiting an emergency department was .41 for patients with an access issue and .27 for those with no access issue (data not shown). Although the likelihood of using emergency department care was higher for those with an access issue, among patients who had at least one emergency department visit there was no statistically significant difference in the number of emergency visits between those who did and those who did not experience medication access problems. Neither the likelihood of having any psychiatric hospitalization nor the number of hospitalization days for those who had at least one psychiatric hospitalization was significantly different for those who did and those who did not experience a medication access problem.

|

Discussion

Dually eligible persons with a psychiatric illness are a particularly vulnerable subgroup of Medicare beneficiaries. Some patient advocates and policy makers were concerned that the shift from Medicaid drug coverage to enrollment in a private Part D plan would result in difficulties accessing medications and possibly lead to negative mental health outcomes for this group. The special protections for medication classes used commonly by individuals with mental disorders were intended to address this concern by guaranteeing formulary coverage of these medications. However, many plans use management tools such as prior authorization and step therapy to control utilization of psychopharmacologic medications. Although use of these tools may lead to a more efficient allocation of resources and could possibly result in higher-quality care in some cases, utilization management requirements can also create access issues for enrollees. For example, Soumerai and colleagues' study ( 13 ) of the policies for prior authorization of second-generation antipsychotics and step therapy that were implemented in Maine's Medicaid program indicated that these policies were associated with a 29% greater risk of antipsychotic discontinuations than would have occurred in a comparison state, with no associated cost savings in drug expenditures. The requirement that all dually eligible beneficiaries make copayments to receive medications may also create access barriers for some of these beneficiaries.

In fact, we found that almost half of the dually eligible patients in our sample experienced some form of medication access problem in 2006. Although one might expect rates of access problems to decline over the course of the year, West and colleagues ( 14 , 15 ) found no decline; in fact, the rate of access problems reported by psychiatrists actually increased slightly as the year progressed, perhaps somewhat as a result of the transition policy. Rates of difficulties with accessing medications might also be expected to decrease after the first year of implementation, although a large number of dually eligible beneficiaries either switch plans or are reassigned to a different benchmark plan each year. Between 2006 and 2007, for example, 1.1 million of these beneficiaries were reassigned to another plan when their plan's premium bid exceeded the new benchmark for the coming year; between 2007 and 2008, a total of 2.1 million were reassigned ( 3 ). Thus, during a given year a large proportion of dually eligible beneficiaries will likely face different coverage and utilization management requirements under a new plan and therefore may be at particular risk of access problems. Access problems may also occur among beneficiaries who remain in the same plan if that plan changes formulary coverage and management procedures.

Although disruptions in medication continuity among psychiatric patients have been shown to be associated with high rates of symptom relapse or exacerbation, hospitalization, and other adverse consequences ( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ), some of the access issues we observed may have been resolved expeditiously, with little harm to the patient. For example, if a claim was initially rejected because prior authorization was required and authorization was granted quickly, the enrollee may have been able to fill the original prescription before a negative health outcome occurred. The timeliness of authorizations has been shown to be critically important for patients with schizophrenia ( 21 ). Consequently, patients who experienced significant disruptions or gaps in medication continuity may have been more likely to relapse and seek emergency care.

Other patients may have switched medications in response to Part D coverage rules, and the effectiveness or tolerability of the substitute medication could have been either better or worse than the prior medication for each patient. Findings from the CATIE study (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) indicate that individuals randomly assigned to receive olanzapine or risperidone who were continuing with the medication they were taking at baseline had a longer time to discontinuation compared with individuals assigned to switch antipsychotics ( 22 ). The consequences of switching medications may vary, however, based on the nature of the switch (such as a therapeutic substitution from one molecule to another versus a generic substitution). We found that patients who experienced an access problem were significantly more likely to have an emergency department visit for the treatment of a psychiatric illness but were not more likely to have a psychiatric hospitalization.

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, we measured patients' experience of a medication access problem and their use of psychiatric emergency department care and hospital care in the first 12 months after Part D's implementation by using reports from their psychiatrist. The psychiatrists may not have been aware of all access problems experienced by their patients and all services used, or recall bias could be an issue if a psychiatrist did not provide sufficient documentation in patients' medical records regarding these issues. We did not have data on the timing of access problems, use of emergency services, and hospitalizations within the 12-month period, which limited our ability to fully examine the relationship between medication access problems and use of these intensive services. Also, the high proportion of patients who experienced medication access problems during 2006, the first year of Part D implementation, likely reflects in part the widespread confusion when Part D was first implemented. The relatively high rate of reported access problems motivated us to use propensity score matching to allow us to compare individuals who were similar with respect to observable demographic and clinical characteristics.

Second, our propensity score models were only able to reduce differences between the intervention and comparison groups in observed confounders; we were unable to control for differences in unobserved confounders. Third, we did not have information on additional office visits that may have resulted from medication access problems (such as a follow-up visit to check on a patient who had to switch medications because of lack of coverage). Finally, the dually eligible patients in our study were all in the care of a psychiatrist, so our findings may not be generalizable to all dually eligible beneficiaries with a psychiatric disorder. However, psychiatrists treat most individuals receiving treatment for schizophrenia and many individuals with other severe mental illnesses, and a disproportionate share of dually eligible beneficiaries have one of these conditions ( 23 , 24 ).

Conclusions

This study documents various ways that dually eligible patients with a psychiatric disorder experienced difficulty accessing medications in the first year after their drug coverage was switched from Medicaid to Part D. We found that patients who experienced a medication access problem were more likely to use emergency psychiatric care but were not more likely to use inpatient psychiatric care. These findings raise concerns about potential offsets and possible negative effects on quality of care that should be examined with other data sources, including the Medicare and Medicaid claims, once available. Additional study of the impact of Part D on use of other social services, on the criminal justice sector, and, more importantly, on the effects on mental health outcomes and functioning for the dually eligible population with psychiatric disorders is also needed.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grants K01-MH-66109 and 1R01-MH-069721 and by a personal services contract from the National Institute of Mental Health. Dr. Huskamp and Dr. Frank were not involved in the collection of the data for this analysis and received no support from the American Psychiatric Foundation (APF). Dr. West, Dr. Rae, and Dr. Rubio-Stipec were supported by a grant from the APF. Although a consortium of industry supporters, including AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Forest, Janssen, Pfizer, and Wyeth, provided financial support to the APF for this research, the authors were given complete discretion and control over the design and conduct of this study and analyses of the resulting database.

1. Donohue J: Mental health in the Medicare Part D drug benefit: a new regulatory model? Health Affairs 25:707–719, 2006Google Scholar

2. Donohue JM, Huskamp HA, Zuvekas SH: Dual-eligibles with mental disorders and Medicare Part D: how are they faring? Health Affairs 28:746–759, 2009Google Scholar

3. Summer L, Hoadley J, Hargraves E, et al: Medicare Part D Data Spotlight: Low-Income Subsidy Plan Availability. Menlo Park, Calif, Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, Nov 2008. Available at www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7836.pdf Google Scholar

4. Hoadley J, Summer L, Thompson J, et al: The Role of Beneficiary-Centered Assignment for Medicare Part D. Pub no 07-4. Washington, DC, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, June 2007. Available at www.medpac.gov/documents/June07_Bene_centered_assignment_contractor.pdf Google Scholar

5. Neuman P, Strollo MK, Guterman S, et al: Medicare prescription drug benefit progress report: findings from a 2006 national survey of seniors. Health Affairs 26:w630–w643, 2007Google Scholar

6. Smith V, Gifford K, Kramer S, et al: The Transition of Dual Eligibles to Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Coverage: State Actions During Implementation. Washington, DC, Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Feb 2006. Available at www.kaiserfamilyfoundation.org/medicaid/upload/7467.pdf Google Scholar

7. Department of Health and Human Services: Medicare program: Medicare Advantage and prescription drug programs, MIPPA drug formulary and protected classes policies. Federal Register 74:2881–2888, 2009Google Scholar

8. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual. Chapter 6. Baltimore, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, July 2008. Available at www.cms.hhs.gov/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/downloads/R2PDBv2.pdf Google Scholar

9. Huskamp HA, Stevenson DG, Donohue JM, et al: Coverage and prior authorization of psychotropic drugs under Medicare Part D. Psychiatric Services 58:308–310, 2007Google Scholar

10. West JC, Wilk JE, Muszynski IL, et al: Medication access and continuity: the experiences of dual-eligible psychiatric patients during the first 4 months of the Medicare prescription drug benefit. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:789–796, 2007Google Scholar

11. D'Agostino RB Jr: Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Statistics in Medicine 17:2265–2281, 1998Google Scholar

12. Imbens GM, Wooldridge JM: Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. Journal of Economic Literature 47:5–86, 2009Google Scholar

13. Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, et al: Use of atypical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia in Maine Medicaid following a policy change. Health Affairs 27:w185–w195, 2008Google Scholar

14. West JC, Wilk JE, Rae DS et al: Medicare prescription drug benefits: medication access and continuity among dual eligible psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

15. West JC, Wilk JE, Rae DS, et al: Medicaid prescription drug policies and medication access and continuity: findings from ten states. Psychiatric Services 60:601–610, 2009Google Scholar

16. Drake RJ, Pickles A, Bentall RP, et al: The evolution of insight, paranoia, and depression during early schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 34:285–292, 2004Google Scholar

17. Opler LA, Caton CL, Shrout P, et al: Symptom profiles and homelessness in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:174–178, 1994Google Scholar

18. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:241–247, 1999Google Scholar

19. Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK: Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatric Services 52:805–811, 2001Google Scholar

20. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Borm R, et al: Involuntary out-patient commitment and reduction of violent behavior in persons with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:324–331, 2000Google Scholar

21. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al: Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 55:886–891, 2004Google Scholar

22. Essock SM, Covell NH, Davis SM, et al: Effectiveness of switching antipsychotic medications. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:2090–2095, 2006Google Scholar

23. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, Survey Co-Investigators of the PORT Project: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–20, 1998Google Scholar

24. Pingitore DP, Scheffler RM, Sentell T, et al: Comparison of psychiatrists and psychologists in clinical practice. Psychiatric Services 53:977–983, 2002Google Scholar