Mental Health Service Use During the Transition to Adulthood for Adolescents Reported to the Child Welfare System

Mental health problems during the transition to adulthood create unique developmental and service delivery challenges. As youths develop from adolescents into adults, they face increasing expectations of independence that include school completion, stable employment, and the ability to support a household ( 1 ). Such expectations may be especially difficult to meet for young adults with a history of mental health problems. Longitudinal research suggests that mental health problems in adolescence are associated with increased risk in young adulthood of dropping out of school, being unemployed, committing crime, abusing substances, and having an unplanned pregnancy ( 2 , 3 ). Consequently, the need for and receipt of mental health services may be particularly critical during this transition to independence ( 4 , 5 ).

National cross-sectional data suggest that young adults are especially unlikely to access mental health services. The National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) found that, regardless of need, use of outpatient mental health services declines from approximately 21% among 12- to 17-year-olds to about 11% among 18- to 25-year-olds. Among adults from all age groups, young adults used outpatient mental health services least (11%, compared with 14% of 26- to 49-year-olds and 13% of those aged 50 years or older) ( 6 ). High insurance instability ( 7 , 8 , 9 ), the movement from a child- to an adult-oriented system, and more restrictive eligibility criteria for adult mental health services may create special obstacles to successful service engagement ( 10 ). Some have suggested that service access in young adulthood may be limited by the difficulty in navigating a complex, adult-oriented service system with extended waiting periods ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). Service models designed for this population emphasize the coordination of mental health and substance abuse treatment with specially designed "transition services" that include vocational, independent-living, and housing support ( 11 ). However, in most states these services are not tailored to the needs of this age group ( 10 ). To improve this population's access to the service delivery system, patterns of mental health service use from adolescence to young adulthood must be understood, along with factors uniquely associated with young adults' access.

Unmet mental health needs in early adulthood may be particularly problematic for those with a history of maltreatment in adolescence. Effects of maltreatment on adolescents are both immediate and long term, with victims at increased risk during adulthood of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, traumatic stress, and substance abuse ( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ). Studies of maltreated children have found that only about one-fourth of those in need of mental health services receive specialty care ( 17 , 18 ). Although studies show high rates of unmet need among adolescents investigated by the child welfare system ( 17 ), little is known about use of mental health services among maltreated adolescents transitioning to early adulthood.

Leading epidemiological studies on mental health service use focus either on children younger than 18 ( 19 , 20 ) or on adults ( 21 ). Some of these national studies have important limitations. For example, the NSDUH provides data on patterns of service use among adolescents and adults, but it does not include any indicator of overarching mental health need of adolescents or young adults. The study presented here benefits from a longitudinal data set that includes indicators of need and use of services, which permits analysis of mental health service use from adolescence into early adulthood in a particularly at-risk sample: young adults whose maltreatment in adolescence was investigated.

More specifically, this study examined mental health need and service use in young adulthood, patterns of outpatient mental health service use from adolescence to young adulthood, and predictors of mental health service use among 18- to 21-year-olds. It addressed factors identified in previous studies as being associated with use of mental health services in childhood: placement history ( 22 , 23 ), insurance status ( 24 ), gender, age ( 22 , 24 ), and race or ethnicity ( 24 , 25 , 26 ). Similarly, it examined factors associated with use of mental health services in adulthood: gender, age, race or ethnicity, insurance status ( 27 ), marital status ( 28 ), and employment ( 29 ). The study also addressed factors known to be related to mental health problems in young adulthood (for example, criminal justice involvement) ( 30 ) because they affect mental health service use. We hypothesized that adolescents reported to the child welfare system as having been maltreated would show particularly high rates of mental health needs during the transition to adulthood, that they would show a decline in mental health service use from adolescence to early adulthood, and that mental health service use in young adulthood would be associated with some factors unique to childhood (that is, history of out-of-home placement) and others central to adulthood (that is, employment).

Methods

Sample

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) is the first national longitudinal study of the well-being of 5,501 children aged 14 or younger who had contact with the child welfare system for allegations that they were maltreated during a 15-month period starting October 1999. Two-stage random sampling was conducted to select 92 primary sampling units located in 97 counties nationwide. The secondary sampling units were children selected from lists of closed investigations or assessments from the sampled agencies. To be eligible for the sample, children had to enter child welfare services through an investigation of child abuse or neglect by Child Protective Services. The sample design required oversampling of infants and sexual abuse cases. The age of children at investigation was capped at 14 years at the time of sampling. Data were collected at baseline and at follow-ups conducted one year (wave 2), 1.5 years (wave 3), three years (wave 4), and five to six years (wave 5) after the investigation. Response rates were 64.2% at baseline, 86.7% at wave 2, 86.6% at wave 3, 85.3% at wave 4, and 85.0% at wave 5. (Percentages are weighted.)

Additional information on NSCAW methods appears elsewhere ( 31 ). The analysis presented here focused on the 620 young adults aged 18 to 21 years at final follow-up (they would have been aged 12 to 15 years at baseline). For this subsample, response rates were 77.6% at wave 3, 77.0% at wave 4, and 81.0% at wave 5. (Percentages are weighted.) Among the young adults, 616 met inclusion criteria (four were excluded for lack of services data).

Procedures

Field representatives trained intensively for 12 days, with emphasis on the practice and administration of child assessment instruments ( 31 ). At baseline, field representatives contacted caregivers and asked permission to interview them and assess their child. These interviews were by computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) in English (N=5,281, 96%) or Spanish (N=220, or 4%) at the children's homes. Caregivers received approximately $40 for participation in each interview. NSCAW also conducted one-hour CAPI sessions with child welfare system caseworkers. At the final follow-up, young adults were directly contacted. Data analyzed here were drawn from baseline and the 1.5-year, three-year, and five- to six-year follow-ups; the final wave was conducted from July 2006 to January 2007. NSCAW, the consent protocols, and this study received institutional review board approval from RTI International and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Measures

Sociodemographic characteristics and placement history. At the five- to six-year follow-up young adults were asked their sex, age, race and ethnicity, household income ( 32 ), insurance, and marital status, whether they had children, and whether they lived with a caregiver ( Table 1 ). They were also asked what their living situation had been (in home versus foster and kinship care) between baseline and the three-year follow-up.

|

Employment. Young adults responded yes or no to the following question regarding employment status: "Are you currently working at a full- or part-time job or jobs?"

Involvement with the law. Young adults answered yes or no to the following question: "In the last 12 months, have you been arrested for any offense?"

Mental health needs. Five measures were used to assess young adults' mental health at the five- to six-year follow-up. The first measure, which indicated whether the respondent felt he or she needed to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital or detox unit in the 12 months preceding the assessment, was based on the following question: "How much would you say you needed to be admitted to a detox unit or inpatient drug or alcohol unit or hospital medical inpatient unit?" Possible responses were 1, a lot; 2, somewhat; and 3, a little. A response of "a lot" or "somewhat" indicated clinical need.

The second measure came from sections of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF) on major depression, alcohol dependence, and drug dependence. The CIDI-SF was developed with use of data from the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey. Internal consistency for the sections ranged from .70 to .94. A respondent was thought to likely have drug or alcohol dependence if he or she declared having used any drug or alcohol in the past 12 months and also gave responses indicating the presence of three or more symptoms of substance dependence. A respondent was thought to likely have experienced major depression if he or she reported three or more symptoms of depression and responded affirmatively to either experiencing two or more weeks of dysphoric mood or anhedonia or to using medication for depression. The time frame examined with this measure is the 12 months preceding assessment ( 33 ).

The intrusive thoughts and dissociation sections of the Trauma Symptoms Inventory (TSI) was the third measure. The TSI is used in the evaluation of acute and chronic posttraumatic symptomatology, including the effects of sequelae of childhood abuse and other early traumatic events. The clinical scales of the TSI have Cronbach's alphas over .80. Young adults classified as having trauma had standardized scores at or above 64 on at least one of the scales ( 34 ).

The externalizing, internalizing, and total problems subscales of the Adult Self-Report (ASR) provided the fourth measure. The ASR is a self-report scale completed by persons aged 18 years or older to describe their own functioning. Cronbach's alphas range from .78 to .94. Young adults classified as having clinical or subthreshold problem behaviors had standardized scores at or above 64 on at least one of the subscales. This scale examines current behavioral problems ( 35 ).

The mental health component of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) provided the fifth measure. The SF-12 includes 12 items selected from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey. It has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity. Young adults classified as having mental health problems had scores two standard deviations below the mean. The time frame examined with this measure is the four weeks preceding assessment ( 36 ).

Mental health services. With an adapted version of the Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA) ( 37 ), information on specialty outpatient mental health service use was collected from caregivers (mostly biological mothers) between baseline and the three-year follow-up and directly from young adults at the five- to six-year follow-up. All questions used as a time frame the past 12 months and described the type of services as being "for emotional, behavioral, learning, attentional, or substance abuse problems." Specialty outpatient service items selected from the CASA were consistent with other leading studies of childhood mental health service use ( 26 , 38 ). From baseline to the three-year follow-up, adolescents also answered two questions on such service use: "In the past six months did you get any kind of professional treatment for an alcohol or drug problem (not provided by a caseworker)?" and "In the past six months did you get any counseling from a school counselor, doctor, or therapist to help you deal with feeling depressed or blue?" A summary variable for outpatient specialty services was created: any use of services was classified as a yes if a respondent answered positively to any question. Although NSCAW asks about inpatient and residential service use, at the five- to six-year follow-up such service use was found to be so infrequent (only 8.5% received inpatient services) that this study restricted analysis to outpatient services.

Analyses

All analyses used weighted data that were calculated with the SUDAAN statistical package, version 9.0.1, to take into account NSCAW's complex sampling design ( 39 , 40 ). Thus all percentages are adjusted (weighted) for sampling probabilities; listed sample sizes are not adjusted. Analyses addressed predictors of use of outpatient specialty mental health services. Pearson chi square tests adapted for complex samples were used to test differences between users and nonusers of outpatient specialty mental health services. Logistic regression analyses modeled mental health services use as a function of mental health problems and young adult characteristics. To avoid very low numbers in the multivariate analysis, the model included only variables statistically significant in the bivariate analysis (p≤.05) or conceptually relevant to the literature.

Results

Mental health needs during young adulthood

Only 2.6% of young adults at the five- to six-year follow-up reported an unmet need to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital; the same percentage reported an unmet need for admission to a detox unit. Scores on the various measures indicated that more than a fourth (27.5%) had experienced major depression, 10.2% had experienced intrusive thoughts, and 6.2% had experienced traumatic dissociation. According to scores on the ASR, 16.0% scored in the clinical range for the internalizing subscale, 18.9% for the externalizing subscale, and 13.4% for the total problem subscale (27.2% had elevated scores in at least one of the ASR subscales); 11% had poor mental health, according to the SF-12; 6.6% had alcohol dependence and 6.5% had drug dependence, according to the CIDI-SF. Overall, 48.1% of young adults had one or more indicators of current mental health needs.

Mental health service use during young adulthood

During the 12 months preceding the final follow-up interview, 14.3% of young adults received outpatient specialty mental health services. Among those identified as having one or more indicators of a mental health need, 23.2% reported having used an outpatient mental health service. For all young adults, use of outpatient specialty mental health services varied significantly by insurance status, and mental health needs ( Table 1 ).

Mental health service use from adolescence to young adulthood

Overall, 47.6% received outpatient specialty mental health services at baseline, 41.0% received them at the 1.5-year follow-up, 33.5% received them at the four-year follow-up, and 14.3% received them at the five- to six-year follow-up. Across all follow-ups the percentage receiving any outpatient specialty mental health services declined significantly ( χ2 =4.44, df=3, p<.001).

Very small percentages of young adults surveyed at the five- to six-year follow-up received day-treatment mental health services and outpatient services at drug or alcohol units ( Table 2 ). Although the decline between baseline and the final follow-up in receipt of services was significant in four of six services, the decline was consistently most marked after baseline for mental health services that were provided in mental health or community health centers. For private services from mental health professionals, strong declines were observed from baseline to the final follow-up. The greatest declines were in use of mental health or community health centers (decline of 80% in use between baseline and the five- to six-year follow-up) and in use of private services from mental health professionals (decline of 73% in the same period).

|

At the five- to six-year follow-up, 8.4% of young adults received inpatient mental health services. Among those in need of mental health services, only 13.3% received inpatient mental health services. These services included use of a psychiatric hospital (4.2%), use of a general hospital for emotional and substance abuse problems (2.3%), residential or group home treatment (1.0%), and emergency department visits for emotional and substance abuse problems (4.5%). Because of the limited number of young adults receiving specialty (psychiatric) inpatient mental health services (15 patients), no further analyses were completed on inpatient services.

Predictors of mental health service use in young adulthood

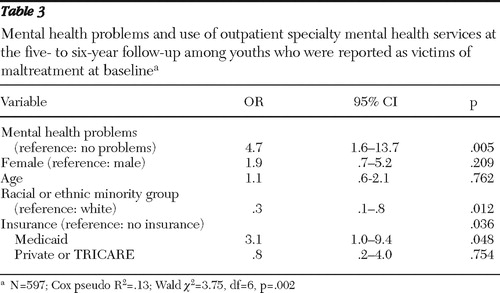

Table 3 reports results of a logistic regression model for examining how young adults' mental health problems, sex, age, race or ethnicity, and insurance status were associated with use of outpatient specialty mental health services during the 12 months before the final follow-up interview. In order to improve the precision of estimates, the racial and ethnic categories were reduced to white versus racial or ethnic minority group and age was used as a continuous variable. Overall, the model significantly predicted outpatient mental health service use for the young adult population with a history of suspected maltreatment (Wald χ2 =3.75, df=6, p=.002). The adjusted odds that youths with mental health needs received outpatient specialty mental health services were more than four times the odds for youths without mental health needs. Young adults from racial or ethnic minority groups were less likely than white young adults to receive outpatient specialty services. Young adults with Medicaid were more than three times as likely as young adults without insurance to receive outpatient specialty mental health services; no significant service use difference was found between young adults with private insurance and those without insurance.

|

Discussion

Services researchers, practitioners, and policy makers have suspected an increase in unmet mental health service needs during the transition to adulthood ( 41 ), but it has never before been documented through prospective methods. This is the first longitudinal study empirically supporting a substantial decline in mental health service use from adolescence to young adulthood in a vulnerable population. Studies of childhood mental health service use have found consistently higher rates of use in adolescence than in childhood ( 22 , 24 ). This study shows a gradual decline in such use throughout adolescence and a sharp decline by young adulthood. These declines hold true across types of services received and across respondents (caregivers and adolescents).

Rates of mental health needs in this young adult population at the five- to six-year follow-up were very high. By the time adolescents who had been investigated for maltreatment reached young adulthood, about half had one or more indicators of mental health needs—almost double the national 12-month estimates for English-speaking respondents aged 18 years or older for any mental disorder (26.2%), as measured by diagnostic interviews ( 42 ).

Comparisons between our sample of young adults at the five- to six-year follow-up and previous studies of maltreated youths show somewhat similar levels of high need. One Midwestern prospective study found major depression rates of 24% to 31.4% among young adults with court-substantiated childhood maltreatment ( 43 ). This is similar to the rate for depression among young adults in our sample at wave 5 (27.5%). Rates of mental health problems among young adults were somewhat higher than among 17-year-olds in the foster care system in eight of Missouri's largest counties, where 37% had some disorder ( 44 ). Nevertheless, comparisons to local samples of young adults maltreated during childhood are problematic—not only because they are not representative of the national child welfare system population but also because local samples use self-report to determine childhood maltreatment or they assess a limited number of mental health needs. Although mental health needs among young adults at the five- to six-year follow-up exceeded national estimates for the general population, they resembled those from earlier studies of young adults previously reported to or placed in the child welfare system ( 45 , 46 , 47 ).

High rates of unmet mental health needs are not unique to young adults with a history of suspected childhood maltreatment. A national study in the general population found that only 21.7% of English-speaking adults aged 18 years or older with a diagnosable mental disorder reported receiving specialty treatment within a 12-month period ( 28 ). Even so, rates of unmet mental health needs are especially high for young adults for whom maltreatment was investigated in adolescence. Given the special risks this population faces, it is not surprising that its mental health service use is slightly higher than the 11% found for 18- to 24-year-olds in the NSDUH general population survey ( 48 ). However, the high number of young adults at the five- to six-year follow-up with indicators of mental health needs (48.1%) contrasts markedly with the limited number of young adults who used an outpatient specialty mental health service in the previous 12 months (23.2%).

Factors in addition to mental health need predicted young adults' use of mental health services. Consistent with the literature on child and adult mental health services ( 28 , 49 , 50 , 51 ), our findings showed that use of these services differed significantly by young adults' race or ethnicity and insurance status. Young adults from racial or ethnic minority groups were less likely than white young adults to receive outpatient specialty mental health services. This finding is consistent with previous studies of maltreated youths in foster care that found that in addition to need (based on behavioral problems), a number of sociodemographic characteristics—such as age and racial or ethnic minority group—are related to service use. Particularly concerning are findings that children from racial or ethnic minority groups are less likely than white children to receive mental health services ( 49 , 50 , 51 ). Ethnic disparities in access to mental health services highlight a significant public health concern for transition-aged youths with a history of child maltreatment. Interventions to improve the quality of care for this high-risk population should particularly support outreach to and engagement of young adults from racial or ethnic minority groups who have a history of involvement in the child welfare system to better tailor interventions to meet their unique developmental needs.

Young adults with Medicaid coverage were more likely to use mental health services than those with no insurance or those with private insurance. Previous NSCAW research has not demonstrated the positive influence of Medicaid on mental health service access ( 17 , 22 ), probably because of this population's lack of variability in insurance status during childhood: most children with a history of involvement in the child welfare system are covered by Medicaid. In the NSCAW sample of young adults, however, insurance status did vary. Moreover, the influence of Medicaid on mental health service access may have special significance for transition-aged youths: many transition-aged youths are ineligible for Medicaid, and Medicaid eligibility may be particularly critical for youths aging out of foster care. Although the Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 allows states to extend Medicaid coverage to 18-, 19-, and 20-year-olds who have been emancipated from foster care, not all states have chosen to implement this option. Our finding that young adults with private insurance were not significantly more likely than those with no insurance to access services also warrants further study.

Surprisingly, mental health service use by young adults was not associated with factors traditionally found in child mental health services research (for example, out-of-home placement) or adult mental health services research (for example, employment). The transition to adulthood is likely not only a unique period developmentally but also a unique period with regard to mental health service use. Employment in early adulthood, for example, has been found to be less stable than in adulthood generally. Perhaps consequently, young adults are less likely to have higher income, as well as health insurance ( 52 ). Similarly, although several studies show that children in the child welfare system with a history of out-of-home placement are better connected with mental health services than children who live at home with their biological parents, because it is hypothesized that the child welfare system acts as a "service gateway" ( 53 ); however, this association probably does not extend to young adulthood, when few, if any, are still connected with the child welfare system.

Some limitations qualify our conclusions. Determination of need cannot be considered equivalent to results of a comprehensive clinical mental health assessment. The needs described here do, however, likely warrant at least referral of the young adult for further assessment of mental health service need. A second limitation is this study's broad definition of mental health service use; this definition should not be construed as service system engagement. Nevertheless, the data suggest that for this population, the rate of service use fails to match need. By any measure, less than a quarter of those in need received outpatient specialty mental health services.

Conclusions

The mental health, social, and financial needs of youths transitioning to adulthood differ from the needs of their child and adult cohorts. Young adults need the support of good health, adequate finances, and helpful communities to bolster their achievement of critical developmental milestones, such as education completion, relationship and financial stability, and parenthood. The attainment of these milestones varies drastically across vulnerable populations ( 5 ) and is likely affected by emotional health status; consequently, theoretical models explaining the complex relationships among need for, access to, and engagement in mental health services should be adapted for the unique needs of a young adult population.

This study benchmarks mental health service use for the vulnerable population of young adults for whom suspected maltreatment as adolescents was reported, offering findings on barriers to and facilitators of such use. These findings are a platform for expanding existing theoretical models to predict access to health services for vulnerable populations ( 54 ). Findings also support calls for models of "transition" services, beginning in adolescence and continuing through young adulthood ( 11 ), that will facilitate positive development into adulthood and support transition from child- to adult-oriented mental health service systems. Future research should explore whether racial or ethnic disparities existing in adolescence widen in early adulthood and should examine the course of inpatient or residential care use from young adulthood to adulthood, characteristics of consistent as opposed to inconsistent service users from adolescence into young adulthood, and the long-term detrimental consequences of young adults' limited use of mental health services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being was developed under contract to RTI International from the Administration of Children and Families (ACF) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The work of this study was partially funded by support from the ACF for the production of the report Adolescents Involved With Child Welfare: A Transition to Adulthood, available at www.acf.hhs.gov . Conclusions do not necessarily represent those of the ACF. The authors thank Jenny Jennings Foerst, Ph.D., for her review and comments on the manuscript.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Settersten RA, Frustenberg FF, Rumbaut RG: On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research, and Public Policy. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005Google Scholar

2. Vander Stoep A, Davis M, Collins D: Transition: a time of developmental and institutional clashes; in Transition to Adulthood: A Resource for Assisting Young People With Emotional or Behavioral Difficulties. Edited by Clark HB, Davis M. Baltimore, Brookes, 1995Google Scholar

3. Armstrong KH, Dedrick RF, Greenbaum PE: Factors associated with community adjustment of young adults with serious emotional disturbance: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 11:66–77, 2003Google Scholar

4. Arnett JJ: Emerging adulthood: what is it and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives 1:68–73, 2007Google Scholar

5. Osgood DW, Foster ME, Flanagan C, et al: Introduction: why focus on the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations?; in On Your Own Without a Net. Edited by Osgood DW, Foster ME, Flanagan C, et al. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005Google Scholar

6. Keenan HT, Runyan DK, Nocera M: Child outcomes and family characteristics 1 year after severe inflicted or noninflicted traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics 117:317–324, 2006Google Scholar

7. Callahan ST, Cooper WO: Gender and uninsurance among young adults in the United States. Pediatrics 113:291–297, 2004Google Scholar

8. Lyons PM, Melton GB: Coping with mental health problems in young adulthood: diversity of need and uniformity of programs; in On Your Own Without a Net. Edited by Osgood DW, Foster ME, Flanagan C, et al. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005Google Scholar

9. Park M, Mulye T, Adams S, et al: The health status of young adults in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health 39:305–317, 2006Google Scholar

10. Davis M, Geller JL, Hunt BA: Within-state availability of transition-to-adulthood services for youths with mental health conditions. Psychiatric Services 57:1594–1599, 2006Google Scholar

11. Clark H, Deschenes N, Jones J: A framework for the development and operation of a transition system; in Transition to Adulthood: A Resource for Assisting Young People With Emotional or Behavioral Difficulties. Edited by Clark HB, Davis M. Baltimore, Brookes, 2000Google Scholar

12. Liebschutz J, Savetsky JB, Saitz R, et al: The relationship between sexual and physical abuse and substance abuse consequences. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 22: 121–128, 2002Google Scholar

13. Speech-Language Disorders and the Speech-Language Pathologist. Rockville, Md, American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Available at www.asha.org/careers/professions/overview/sld.htm Google Scholar

14. Widom CS, Marmorstein NR, White HR: Childhood victimization and illicit drug use in middle adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 20:394–403, 2006Google Scholar

15. Widom CS, Weiler BL, Cottler LB: Childhood victimization and drug abuse: a comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:867–880, 1999Google Scholar

16. Lo CC, Cheng TC: The impact of childhood maltreatment on young adults' substance abuse. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 33:139–146, 2007Google Scholar

17. Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, et al: Mental health need and access to mental health services by youth involved with child welfare: a national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 43:960–970, 2004Google Scholar

18. McCarthy J, Van Buren E, Irvine E: Child and family services reviews: 2001–2004: a mental health analysis. Washington, DC, National Technical Assistance Center for Children's Mental Health, Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, Technical Assistance Partnership for Child and Family Mental Health, American Institutes for Research, 2007. Available at gucchd.georgetown.edu/files/products_publications/TACenter/cfsr_analysis.pdf Google Scholar

19. Leaf PJ, Alegria M, Cohen P, et al: Mental health service use in the community and schools: results from the four-community MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:889–897, 1996Google Scholar

20. Costello E, Angold A, Burns BJ, et al: The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:1129–1136, 1996Google Scholar

21. Kessler RC, Merikangas KR: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:60–68, 2004Google Scholar

22. Hurlburt MS, Leslie LK, Landsverk J, et al: Contextual predictors of mental health service use among children open to child welfare. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:1217–1224, 2004Google Scholar

23. Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, Landsverk J, et al: Outpatient mental health services for children in foster care: a national perspective. Child Abuse and Neglect 28:699–714, 2004Google Scholar

24. Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB: Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1548–1555, 2002Google Scholar

25. McMiller WP, Weisz JR: Help-seeking preceding mental health clinic intake among African-American, Latino, and Caucasian youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:1086–1093, 1996Google Scholar

26. Garland AF, Lau AS, Yeh M, et al: Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:1336–1343, 2005Google Scholar

27. Elhai JD, Ford JD: Correlates of mental health service use intensity in the National Comorbidity Survey and National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychiatric Services 58:1108–1115, 2007Google Scholar

28. Wang MQ, Matthew RF, Bellamy N, et al: A structural model of the substance use pathways among minority youth. American Journal of Health Behavior 29:531–541, 2005Google Scholar

29. Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H: Help seeking for psychiatric disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:935–942, 1997Google Scholar

30. Vander Stoep A, Beresford SA, Weiss NS, et al: Community-based study of the transition to adulthood for adolescents with psychiatric disorder. American Journal of Epidemiology 152:352–362, 2000Google Scholar

31. NSCAW Research Group. Methodological lessons from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being: the first three years of the USA's first national probability study of children and families investigated for abuse and neglect. Children and Youth Services Review 24:513–541, 2002Google Scholar

32. Dalaker J: Poverty in the United States: 2000. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2001. Available at www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/p60-214.pdf Google Scholar

33. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171–185, 1998Google Scholar

34. Briere J: Trauma Symptom Inventory (TSI) Professional Manual. Lutz, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1996Google Scholar

35. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA: Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms and Profiles. Burlington, University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth and Families, 2003Google Scholar

36. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34:220–233, 1996Google Scholar

37. Ascher BH, Farmer EMZ, Burns BJ, et al: The Child and Adolescent Services Assessment (CASA): description and psychometrics. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 4:12–20, 1996Google Scholar

38. Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, Stiffman AR, et al: Reliability of the services assessment for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 52:1088–1094, 2001Google Scholar

39. SUDAAN User's Manual, Release 9.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC, RTI International, 2007Google Scholar

40. Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, et al: The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:979–986, 1994Google Scholar

41. Davis M, Vander Stoep A: The transition to adulthood among children and adolescents who have serious emotional disturbance: part I. developmental transitions. Journal of Mental Health Administration 24:400–427, 1997Google Scholar

42. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:593–602, 2005Google Scholar

43. Widom CS, White HR, Czaja SJ, et al: Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on alcohol use and excessive drinking in middle adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 68:317–326, 2007Google Scholar

44. McMillen JC, Zima BT, Scott LD Jr, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:88–95, 2005Google Scholar

45. Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT: Physical punishment/maltreatment during childhood and adjustment in young adulthood. Journal of Child Abuse and Neglect 21:617–630, 1997Google Scholar

46. MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, et al: Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:1878–1883, 2001Google Scholar

47. Silverman AB, Reinherz HZ, Giaconia RM: The long-term sequelae of child and adolescent abuse: a longitudinal community study. Child Abuse and Neglect 20:709–723, 1996Google Scholar

48. Results From the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. DHHS pub no SMA 06-4194, NSDUH Series H-30. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2006. Available at oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k5nsduh/2k5Results.pdf Google Scholar

49. McMillen JC, Scott LD, Zima BT, et al: Use of mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatric Services 55:811–817, 2004Google Scholar

50. Garland AF, Besinger BA: Racial/ethnic differences in court referred pathways to mental health services for children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review 19:651–666, 1997Google Scholar

51. Horowitz LA, Putnam FW, Noll JG, et al: Factors affecting utilization of treatment services by sexually abused girls. Child Abuse and Neglect 21:35–48, 1997Google Scholar

52. Bernhardt A, Morris M, Handcock MS, et al: Trends in job instability and wages for young adult men. Journal of Labor Economics 17:S65–S90, 1999Google Scholar

53. Leslie LK, Hurlburt MS, James S, et al: Relationship between entry into child welfare and mental health service use. Psychiatric Services 56:981–987, 2005Google Scholar

54. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar