Americans' Attitudes Toward Psychiatric Medications: 1998–2006

This study examined recent trends in opinions of the U.S. general population about benefits and risks of psychiatric medications and willingness to take them. Whereas the rapid increase in the use of psychiatric medications in the United States in recent decades has been well documented ( 1 , 2 ), little is known about changes in public attitudes toward these medications. A study based on data from the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) and National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), found that Americans' attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking in general became more favorable between 1992 and 2003 ( 3 ). That study, however, did not specifically examine trends in attitudes toward the use of psychiatric medications.

Studies from other countries have recorded more favorable public attitudes toward psychiatric medications in recent years compared with earlier times ( 4 , 5 ). For example, national surveys in Australia found that compared with participants in the 1995 survey, respondents in 2003–2004 were more likely to view psychiatric medications as helpful for treatment of patients with depression or schizophrenia and less likely to view the medications as harmful ( 5 ).

In similar population surveys in Germany, the percentage of participants who recommended psychiatric medications for treatment of depression increased from 29% in 1990 to nearly 40% in 2001 ( 4 ). The percentage of participants who advised against use of medications for depression did not change appreciably across the two surveys: 36% versus 38%, respectively. The authors interpreted their results as indicating a growing concordance between the public and mental health professionals regarding views on the treatment of mental disorders ( 4 , 5 ). Furthermore, the authors attributed the changes in public attitudes to improvements in psychiatric treatment, increased public awareness and knowledge about mental disorders and their appropriate treatment, and a general trend in society toward professionalization. Although the reasons for these changes in public attitudes remain to be fully understood, favorable public attitudes are likely to exert a significant impact on demand for such services in the community ( 6 ).

The period since 1998 has witnessed a number of developments in the United States that could affect public attitudes toward psychiatric medications. These include the expansion in the use of mental health services and treatments ( 1 , 7 , 8 ), the rapid growth of the direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals ( 9 , 10 ), the new findings about the relative risks and benefits of antidepressants and antipsychotics for both adults and children ( 11 , 12 ), debates about the value and impact of the Food and Drug Administration's black-box warnings about the use of antidepressants by adolescents and young adults ( 13 , 14 ), and revelations about links between pharmaceutical companies and academic researchers ( 15 , 16 ).

An earlier study by Croghan and colleagues ( 17 ) that examined public attitudes toward psychiatric medications and used data from the 1998 U.S. General Social Survey (GSS) found that most participants had a favorable view of psychiatric medications. The study reported here expanded and updated the findings of that seminal study by comparing 2006 GSS participants' attitudes toward psychiatric medications with those of the 1998 participants. This study further examined whether any changes in opinion were more pronounced about benefits or risks of medications or were more pronounced for some benefits and risks than others; whether willingness to take medications varied to a greater extent for some hypothetical situations than others; and whether any changes in opinions or willingness to take medications were more pronounced in certain sociodemographic groups than in others.

Methods

Sample

The GSS is a biennial cross-sectional survey of behaviors and attitudes of the U.S. general population. It is conducted by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago ( 18 ). The survey is administered in face-to-face interviews that last about 90 minutes. In addition to a core module, which is repeated in each round of the survey and collects basic demographic, behavioral,and attitudinal information, various "topical modules" are administered in each round to all participants or to subsets of participants. For example, the 1998 survey included a module on religious affiliations and practices, and the 2006 survey included a module on opinions about gun control.

Questions about attitudes toward psychiatric medications were included in a health and medical care module in the 1998 and 2006 GSSs. A total of 2,832 adults participated in the 1998 survey and 4,510 participated in 2006, with response rates of 76% and 71%, respectively. Questions about attitudes were administered to 1,387 participants in 1998 and to 1,437 in 2006. The GSS was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Chicago.

Assessments

Questions about attitudes toward psychiatric medications were somewhat more detailed in the 1998 survey than in the 2006 survey. However, to make results of both surveys comparable, the analyses reported here were limited to questions asked in both surveys. These comprised four questions assessing opinions about the benefits of psychiatric medications, including helping people deal with day-to-day stresses, making relationships with family and friends easier, helping people control their symptoms, and helping people to feel better about themselves. Two questions assessed opinions about risks of medications, including potential physical harm and interference with daily activities. Four questions assessed willingness to take these medications in different hypothetical situations, including trouble in personal life, difficulty coping with stresses, symptoms of major depression (feeling depressed, tired, or worthless and having trouble sleeping and concentrating), and symptoms of panic attacks (having periods of intense fear with no apparent reason and trembling, sweating, feeling dizzy, and fearing loss of control or going crazy). Responses were rated on 5-point Likert scales ranging from strongly agree, 5, to strongly disagree, 1, for opinions about benefits and risks of medications. Willingness to take medications was rated from very likely, 5, to very unlikely, 1.

The participants' basic sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, race and ethnicity, and education, were also recorded and adjusted for in the multivariate analyses. Several previous studies have shown these variables to be associated with public attitudes toward mental health treatments ( 1 , 17 , 19 ).

Analysis

Analyses were conducted in four stages. First, change across survey years was examined for each question. In a series of bivariate ordinal logistic regression models the rating of opinion or willingness to take medications was the dependent variable and survey year (0 for 1998 and 1 for 2006) was the independent variable of interest. The odds ratios from these analyses reflect the likelihood of having a higher degree of agreement with the opinion statements or a greater willingness to take medications in 2006 compared with 1998. "Don't know" and missing responses were excluded from these analyses. Missing data were found in 3% to 10% of responses, depending on the specific question.

Further analyses showed a greater number of cases with missing data among black respondents and in the group aged 65 and older. The median percentage with missing values on ratings of opinions and willingness to take medications was 12% (range 5%–16%) among black respondents and 15% (range 6%–22%) in the ≥65-year age group. Furthermore, on four of the ten ratings, 1998 respondents had a greater number of missing values compared with 2006 respondents. However, the median percentage of missing responses in 1998 was 8% (range 3%–12%). Thus, even in these groups with a higher prevalence of missing data, the percentage was relatively small.

In the second stage of analysis, opinions within each category (that is, the two categories of opinions about benefits and risks) were compared with each other, as were ratings of willingness to take medications in different hypothetical situations. Analyses were conducted with bivariate ordinal logistic regression models; the ordinal response categories were the dependent variable, and dummy variables identifying each question within the category were the independent variables. These analyses examined whether certain opinions were more strongly held than others and whether the participants were more willing to use medication for certain conditions than others. In addition the interaction terms of the time variable with these dummy variables were tested. These terms assessed whether changes in time varied across different opinions or willingness ratings.

In the third stage of analysis, changes in attitudes were examined in multivariate models that adjusted for gender, age, race-ethnicity, and education. To avoid spurious results from multiple testing, the models computed average scores for ratings of opinions and willingness to take medications. Furthermore, interaction terms of each sociodemographic characteristic with the survey year variable were entered into the models to examine whether changes in time differed across sociodemographic groups.

The fourth stage assessed the association of the respondents' willingness to use psychiatric medications with their opinions about benefits or risks of medications. Bivariate analyses were conducted separately for the two survey years, and a multivariate analysis was conducted in the combined sample. The summary rating of willingness to take medications (the average of the willingness ratings) was the dependent variable in these ordinal logistic regression analyses. Individual opinion scores as well as the averaged opinion scores were the independent variables of interest in the bivariate models, and the summary opinion scores were the independent variables of interest in the combined model. The multivariate analyses also adjusted for the sociodemographic variables noted earlier.

A level of p<.01 was used for judging the statistical significance of the results. Stata statistical software, release 10.0, was used for the analyses ( 20 ). Analyses adjusted for survey weights, and all percentages reported are weighted.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

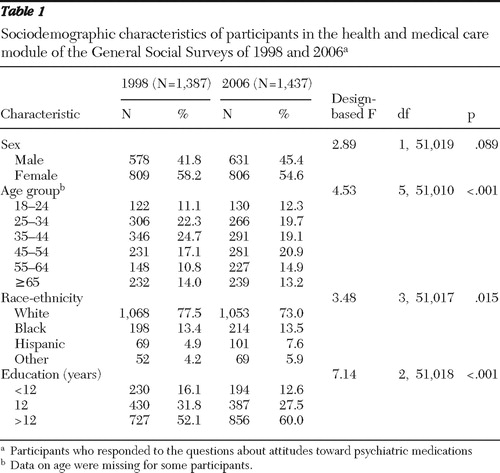

A majority of participants in 1998 and 2006 were female and white and had at least a high school education ( Table 1 ). Although there were statistically significant differences in age and education in the two samples, these differences were small. The mean and the 99% confidence intervals (CIs) for age of the sample were 44.0 (CI=43.1–45.0) in 1998 and 44.9 (CI=43.9–45.9) in 2006; education averaged 13.3 years (CI=13.1–13.4) and 13.7 years (CI=13.5–13.9), respectively.

|

Bivariate analyses of opinions and willingness to take medications

Participants in 2006 agreed more strongly than those in 1998 with statements about the benefits of psychiatric medications ( Table 2 ). Opinions became more favorable at a statistically significant level on all items. The one exception was the opinion that medications help people control their symptoms (p=.013), which was already strongly endorsed in 1998. The percentages of participants who thought (agreed or strongly agreed) that medications help people to deal with day-to-day stresses increased from 77.8% in 1998 to 83.4% in 2006; those who thought that medications make things easier in relationships with family and friends increased from 68.4% to 75.9%; and those who thought that medications help people feel better about themselves increased from 60.1% to 68.0% ( Table 2 ). Changes in opinions about medication risks were smaller, and neither reached a statistically significant level ( Table 2 ). Participants were also significantly more willing to take medications in all hypothetical situations in the later survey.

|

The percentages of participants who were willing (likely or very likely) to take medications because of having trouble in their personal life increased from 23.3% in 1998 to 29.1% in 2006. The percentage who were willing to take medications to cope with stresses of life increased from 35.5% to 46.6%. Those who were willing to take medications for depression increased from 41.2% to 49.1%, and those who were willing to take medications for panic attacks increased from 55.6% to 63.7% ( Table 2 ).

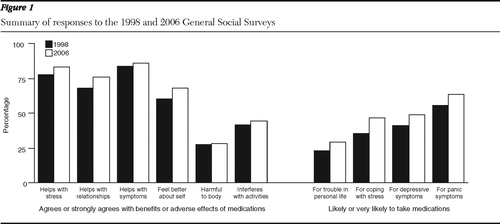

Variations in ratings of opinions and willingness to take medications

Within opinion categories (benefits and risks) and willingness ratings, time trends were similar across specific opinions and willingness ratings. That is, the differences among specific opinions within each category and among specific willingness ratings were similar across the two survey years ( Figure 1 ). The analyses for comparing different opinions and willingness ratings were therefore conducted with the 1998 and 2006 samples combined.

These analyses showed that the participants distinguished between different benefits of psychiatric medications (F=141.37, df=3 and 2,682, p<.001). They were more likely to agree or strongly agree with the statement that taking medications helps people control their symptoms (85.1%), followed by the statement that it helps people deal with day-to-day stresses (80.7%), makes relationships easier with family and friends (72.3%), and helps people feel better about themselves (64.2%).

The participants also distinguished between different risks of psychiatric medications (F=164.36, df=1 and 2,640, p<.001). They were more likely to agree or strongly agree that taking medications interferes with daily activities (43.3%) than that medications are harmful to the body (28.0%).

Furthermore, comparisons of average ratings across opinions about benefits and risks of medications indicated a statistically significant difference (F=650.45, df=1 and 2,714, p<.001). Participants were more likely to agree with statements regarding benefits of medications than with statements regarding risks.

The participants also reported different levels of willingness to take medications in various hypothetical situations (F=320.79, df=3 and 2,751, p<.001). They were most willing to take medications for symptoms of panic attacks (59.8% reported being very likely or somewhat likely to take medications), followed by relief of depressive symptoms (45.2%), inability to cope with stresses of life (41.1%), and troubles in personal life (26.2%).

Changes in average opinion ratings and willingness

Despite variation within categories of opinions and willingness to take medications, responses within each category were strongly correlated. For opinions about benefits of medications, Spearman correlations ranged between .42 and .60 in the 1998 GSS and between .45 and .65 in the 2006 GSS. For opinions about risks, the correlations between the two items were .42 in 1998 and .49 in 2006. For willingness to take medications, correlations ranged between .45 and .76 in 1998 and between .41 and .74 in 2006. Correlations between opinions about benefits of medications and opinions about their risks ranged between -.21 and -.31 in 1998 and between -.16 and -.31 in 2006.

In view of the strong correlations within categories, ratings within each category were combined and three averaged scores were computed: one for opinions about benefits of medications (1998 Cronbach's α =.80, 2006 α =.82), one for opinions about their risks (1998 α =.61, 2006 α =.68), and one for willingness to take medications ( α =.88 and .80, respectively).

Analyses using these averaged scores revealed more favorable opinions about benefits of psychotropic medications (unadjusted odds ratio [UOR]=1.46, CI=1.19–1.79, p<.001) and greater willingness to take them (UOR=1.62, CI=1.34–1.96, p<.001) in 2006 than in 1998. Change in average rating of opinions about risks of medications did not reach a significant level.

Multivariate analyses

The results of bivariate analyses were confirmed in multivariate models that adjusted for sex, age, race-ethnicity, and education. Survey year remained a statistically significant predictor of opinions about benefits of psychiatric medications (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.46, 99% CI=1.19–1.79, p<.001) and willingness to take medications (AOR=1.66, CI=1.36–2.02, p<.001). In addition, women were more likely than men to endorse opinions about benefits of medications (AOR=1.23, CI=1.00–1.50, p=.009), to disagree with statements about risks (AOR=.69, CI=.57–.85, p<.001), and to be willing to take medications (AOR=1.25, CI=1.03–1.52, p=.003). Participants from racial-ethnic minority groups were more likely than majority whites to endorse opinions about risks of medications (AOR for black respondents=1.97, CI=1.46–2.65, p<.001; Hispanics, AOR=1.86, CI=1.33–2.62, p<.001; and for respondents from other racial-ethnic minority groups, AOR=2.07, CI=1.33–3.25, p<.001). Black respondents were less willing than others to take medications (AOR=.54, CI=.40–.71, p<.001).

Compared with the participants with less than 12 years of education, those with more than 12 years of education endorsed opinions about risks of medications less strongly (AOR=.45, CI=.32–.62, p<.001). However, the participants with 12 years or more of education were less willing than those with less than 12 years of education to take psychiatric medications (for participants with 12 years of education, AOR=.71, CI=.51–.98, p=.006; for those with ≥12 years of education, AOR=.73, CI=.54–.99, p=.007). None of the interaction terms with survey year were statistically significant, suggesting that changes in time were not significantly different across sociodemographic groups.

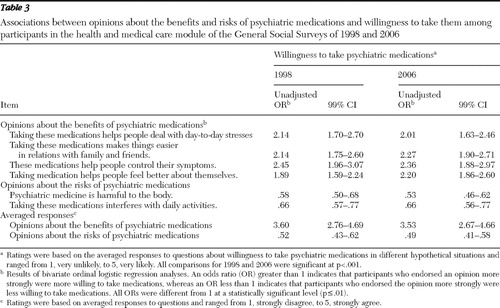

Opinions on effects of medications and willingness to take them

In bivariate ordinal regression analyses within each survey year, greater agreement with statements about benefits of psychiatric medications were associated with greater willingness to take these medications, whereas greater agreement with statements about risks were associated with less willingness ( Table 3 ). Results from the multivariate analysis of the combined 1998 and 2006 samples in which survey year and sociodemographic characteristics were entered along with averaged opinion ratings as independent variables were consistent with these results. Participants with greater agreement with statements about the benefits of psychiatric medications were more willing to take medications (AOR=2.87, CI=2.33–3.53, p<.001), whereas those with greater agreement with statements about the risks of medications were less willing to take them (AOR=.61, CI=.54–.70, p<.001). However, opinions about the effects of medications explained only part of the change in willingness to take medications in this analysis because the coefficient for survey year remained statistically significant (AOR=1.55, CI=1.26–1.90, p<.001), indicating that variations across time in willingness to take medications cannot be fully explained by changes in opinions about the benefits and risks of medications.

|

Discussion

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, the examination of benefits and risks of medications and situations in which persons are willing to take medications was not exhaustive. For example, a common concern of many consumers of psychiatric medications is the fear of dependency on medications, which was not assessed in this study. Furthermore, perceptions of severity of illness and the resultant impairment, which likely influence attitudes toward the use of medications, were not assessed.

Second, the 1998 survey included a question regarding whether the participant or someone whom the participant knew had seen a mental health professional. Participants who responded positively to this question also reported being more willing to use psychiatric medications ( 17 ). Because of the increased use of mental health services in recent years, a larger proportion of the participants in the more recent survey likely either used services or knew people who used services, which could partly explain greater willingness to use medications in more recent years. However, the questions about service use and knowledge of others who have used services were very different in the 1998 and 2006 GSSs. Therefore, the impact of changes in service use on changes in opinions and willingness to take medications could not be assessed.

Third, this study examined attitudes toward psychiatric medications as a whole. However, members of the general public appear to be able to distinguish between different types of psychiatric medication and their indications for specific conditions ( 5 ). Future studies need to assess attitudes toward specific medication groups separately.

Fourth, this study was based on attitudes measured at two time points. Establishing time trends would require assessments at a greater number of time points. Fifth, the observed changes in opinions and willingness might be a result of changes in the interpretation of the questions across time. However, the changes in attitudes and willingness ratings occurred almost uniformly on all questions, whereas one might expect the changes in interpretation to affect some questions more than others.

In the context of these limitations, the results of this study reveal significant consistencies as well as changes in public attitudes toward psychiatric medications between 1998 and 2006. At both time points, the American public appeared to have a generally favorable attitude toward psychiatric medications. A large majority were of the opinion that psychiatric medications help people to deal with day-to-day stresses, control their symptoms, and make relationships with family and friends easier. A majority also thought that psychiatric medications help people feel better about themselves. In contrast, only a minority thought that psychiatric medications are harmful to the body or interfere with daily activities. Thus, overall, Americans hold a favorable view of psychiatric medications and their attitudes toward them have become more favorable in more recent years.

The discrepancy in patterns of change in opinions about benefits of medications and their risks is intriguing. Research in other countries regarding variations in time trends in attitudes toward the benefits and risks of medications has produced mixed results ( 4 , 5 ).

In both Australia and Germany, participants in recent surveys were more likely than those participating in surveys in the 1990s to have a favorable attitude toward the use of psychiatric medications when presented with case vignettes describing individuals with depression and schizophrenia ( 4 , 5 ). Furthermore, in the Australian study, participants in 2003–2004 were less likely than those in 1995 to rate antidepressants as harmful for treatment of depression and antipsychotics as harmful for treatment of schizophrenia. The trend in attitudes toward use of antipsychotic medications to treat schizophrenia, however, did not reach statistical significance in the Australian study.

In the German study, which did not distinguish between types of psychiatric medications, participants in 2001 were less likely than those in 1990 to advise against using psychiatric medications after reviewing a vignette about a person with schizophrenia. However, given a depression vignette, about the same percentage of participants advised against using psychotropic medications in 2001 as in 1990, similar to the GSS results reported here.

Unlike the Australian and the German studies, the GSS items regarding attitudes toward medications did not distinguish between different psychiatric medications or different psychiatric conditions. The comparison with other settings is further complicated by the growth of direct-to-consumer advertising in the United States over the past decade ( 21 ). Much of the advertising in the mass media about psychiatric medications describes the benefits of these medications in vague and qualitative terms ( 22 ). Also, more information is provided about benefits than is provided about side effects ( 23 ). Future research needs to examine whether these factors have contributed to the patterns of change in opinions about benefits and risks of psychiatric medications.

The consistency of findings in this study with those of other countries regarding more favorable attitudes toward the use of psychiatric medications in more recent years suggests a global trend. The reasons for this trend, however, are less well understood. Possible contributors include the continued medicalization of individual and social problems, the introduction and wider availability of newer medications with arguably fewer side effects ( 24 , 25 , 26 ), increased knowledge of mental health conditions and their appropriate treatments as a result of media and information campaigns ( 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ), and greater use of mental health services and psychiatric medications in the individual's social circle ( 2 , 31 ).

Not surprisingly, more favorable opinions were associated with an increased willingness to take psychiatric medications. However, whereas a majority of participants endorsed most questions regarding the beneficial effects of medications, only a minority expressed willingness to take them for most hypothetical situations presented. As noted by Croghan and colleagues in their study of the 1998 GSS ( 17 ), "Americans believe that psychiatric medications are effective at relieving symptoms associated with mental disorders, yet they are relatively unwilling to use them in most situations." This relative unwillingness persisted in 2006.

It is also notable that opinions about benefits of medications and concerns about their risks could not fully explain the change in willingness to take medications across time, given that the variable of survey year remained statistically significant in the multivariate model. These findings suggest that other factors besides considerations about benefits or risks of medications likely contributed to willingness to take psychiatric medications. The role of these other factors needs to be explored in future studies.

Another consistent finding in the 1998 and 2006 surveys was that the participants were more likely to express willingness to take medications for symptoms of panic attacks and depression than for conditions that do not conform to specific psychiatric syndromes, such as having trouble in personal life or an inability to cope with stresses. However, remarkably, willingness to use psychiatric medications increased in all four hypothetical situations. This finding is consistent with the finding of growing use of antidepressant medications in the community among individuals who do not meet the criteria for mood or anxiety disorders ( 2 , 32 , 33 , 34 ). Because the prevalence of problems such as trouble in personal life and inability to cope with stresses is likely to be higher than the prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders, changes in willingness to take medications for these conditions would likely have a large impact on the demand for psychiatric medications in coming years. This finding calls for a more targeted and selective approach in public information campaigns aimed at improving public understanding of the proper uses of psychiatric medications.

Conclusions

Traditionally, negative attitudes have been among the greatest challenges in treatment of common mental health conditions in the community. Therefore, a more favorable public attitude toward mental health treatments in general, and psychiatric medications in particular, is a welcome development. However, with the increasing public acceptance of treatments, psychiatry faces the new and growing challenge of educating the public and providers to correctly identify conditions that merit the use of psychiatric medications and to distinguish these conditions from self-limited stresses of daily life that do not require medication treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Mojtabai has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals.

1. Mojtabai R: Increase in antidepressant medication in the US adult population between 1990 and 2003. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 77:83–92, 2008Google Scholar

2. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Strombom IM, et al: Ecological studies of antidepressant treatment and suicidal risks. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 15:133–145, 2007Google Scholar

3. Mojtabai R: Americans' attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking: 1990–2003. Psychiatric Services 58:642–651, 2007Google Scholar

4. Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H: Have there been any changes in the public's attitudes towards psychiatric treatment? Results from representative population surveys in Germany in the years 1990 and 2001. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 111:68–73, 2005Google Scholar

5. Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM: The public's ability to recognize mental disorders and their beliefs about treatment: changes in Australia over 8 years. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40:36–41, 2006Google Scholar

6. Jorm AF, Angermeyer MC, Katschnig H: Public knowledge of and attitudes to mental disorders: a limiting factor in the optimal use of treatment services; in Unmet Need in Psychiatry. Edited by Andrews G, Henderson S. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2000Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar

8. Paulose-Ram R, Safran MA, Jonas BS, et al: Trends in psychotropic medication use among US adults. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 16:560–570, 2007Google Scholar

9. Donohue JM, Cevasco M, Rosenthal MB: A decade of direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription drugs. New England Journal of Medicine 357:673–681, 2007Google Scholar

10. Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, et al: Influence of patients' requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293:1995–2002, 2005Google Scholar

11. Jureidini JN, Doecke CJ, Mansfield PR, et al: Efficacy and safety of antidepressants for children and adolescents. British Medical Journal 328:879–883, 2004Google Scholar

12. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 353:1209–1223, 2005Google Scholar

13. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, et al: Early evidence on the effects of regulators' suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1356–1363, 2007Google Scholar

14. Simon GE, Savarino J: Suicide attempts among patients starting depression treatment with medications or psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1029–1034, 2007Google Scholar

15. DeAngelis CD, Fontanarosa PB: Impugning the integrity of medical science: the adverse effects of industry influence. JAMA 299:1833–1835, 2008Google Scholar

16. Harris G: Top psychiatrist didn't report drug makers' pay. New York Times, Oct 4, 2008, p A1Google Scholar

17. Croghan TW, Tomlin M, Pescosolido BA, et al: American attitudes toward and willingness to use psychiatric medications. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:166–174, 2003Google Scholar

18. Davis JA, Smith TW, Marsden PV: General Social Surveys: 1972–1998. Chicago, National Opinion Research Center, 1998Google Scholar

19. Angermeyer MC, Breier P, Dietrich S, et al: Public attitudes toward psychiatric treatment: an international comparison. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 40:855–864, 2005Google Scholar

20. Stata Statistical Software, Release 10. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2008Google Scholar

21. Jeffords JM: Direct-to-consumer drug advertising: you get what you pay for. Health Affairs Web Exclusives W4-253–255, 2004Google Scholar

22. Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Tremmel J, et al: Direct-to-consumer advertisements for prescription drugs: what are Americans being sold? Lancet 358:1141–1146, 2001Google Scholar

23. Kaphingst KA, Dejong W, Rudd RE, et al: A content analysis of direct-to-consumer television prescription drug advertisements. Journal of Health Communication 9:515–528, 2004Google Scholar

24. Healy D: Let Them Eat Prozac: The Unhealthy Relationship Between the Pharmaceutical Industry and Depression. New York, New York University Press, 2006Google Scholar

25. Anderson IM: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Journal of Affective Disorders 58:19–36, 2000Google Scholar

26. Arroll B, Macgillivray S, Ogston S, et al: Efficacy and tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs compared with placebo for treatment of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Annals of Family Medicine 3:449–456, 2005Google Scholar

27. Paykel ES, Hart D, Priest RG: Changes in public attitudes to depression during the Defeat Depression Campaign. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:519–522, 1998Google Scholar

28. Jorm AF, Christensen H, Griffiths KM: The impact of Beyondblue: The National Depression Initiative on the Australian public's recognition of depression and beliefs about treatments. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 39:248–254, 2005Google Scholar

29. Jacobs DG: National Depression Screening Day: Educating the public, reaching those in need of treatment, and broadening professional understanding. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 3:156–159, 1995Google Scholar

30. Olfson M, Guardino M, Struening E, et al: Barriers to the treatment of social anxiety. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:521–527, 2000Google Scholar

31. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203–209, 2002Google Scholar

32. Croghan TW: The controversy of increased spending for antidepressants. Health Affairs 20(2):129–135, 2001Google Scholar

33. Druss BG: Rising mental health costs: what are we getting for our money? Health Affairs 25:614–622, 2006Google Scholar

34. Walton SM, Schumock GT, Lee KV, et al: Prioritizing future research on off-label prescribing: results of a quantitative evaluation. Pharmacotherapy 28:1443–1452, 2008Google Scholar