Dropout From Outpatient Mental Health Care in the United States

Many outpatients fail to complete the recommended course of treatment ( 1 , 2 ). Patient-initiated treatment dropout is widespread ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ) and limits treatment effectiveness ( 8 , 9 ). Because patients commonly receive mental health treatment from several different professionals ( 10 , 11 ), focusing on a single treatment sector may overstate dropout from all sources of care.

Few studies have compared treatment dropout across multiple treatment sectors. One recent Canadian study reported that dropping out of treatment—defined as stopping before completing recommended treatment or before improvement—was lowest for patients treated by primary care physicians (12%), followed by psychologists (22%), psychiatrists (23%), and nurses (29%) ( 1 ). A combined analysis of data from the National Comorbidity Survey (1990–1992) and the Ontario Health Survey (1990) found that dropout was lower among patients treated within settings that could provide psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy than among other settings ( 12 ). Neither study assessed treatment continuity for individuals across sectors, a key domain of care continuity.

Gender has not been found to predict dropout ( 12 ), although younger adults may be more likely than older clients to drop out ( 1 , 12 , 13 ). Ethnic minority status ( 1 ) and socioeconomic disadvantage, including low income ( 12 ), lack of health insurance ( 2 , 12 ), lower educational attainment ( 13 ), and unemployment ( 13 ), have been linked to dropout. Findings have been inconsistent across studies, however, perhaps because of methodological differences.

In the study reported here, a uniform definition of treatment dropout was applied to a nationally representative sample of adults with a range of disorders who received care from several treatment sectors. We explored patient sociodemographic and clinical factors related to early and late dropout. We seek to inform efforts to understand the clinical significance of dropout and improve treatment engagement and outcomes.

Methods

Sample

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is a nationally representative household survey of adults aged 18 and older in the coterminous United States ( 14 ). Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 9,282 respondents from 2001 through 2003 by professional interviewers. The response rate was 70.9%. Part I included a core diagnostic assessment of DSM-IV mental disorders that was administered to all 9,282 respondents, along with questions on service use and pharmacology. Part II included questions about correlates and additional disorders. Part II was administered to a probability subsample of 5,692 part I respondents that included all of those who met lifetime criteria for any disorder in the part I assessment and a probability subsample of other respondents. The analysis for the study reported here was limited to part II respondents who reported treatment in the past 12 months for problems with "emotions or nerves" or drug or alcohol use (N=1,164). NCS-R procedures were approved by the human subjects committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

Measures

Mental health service sectors. Sources of care were classified into four sectors: psychiatrist, other mental health specialty sector treatment (a psychologist or other nonpsychiatrist mental health professional in any setting or a social worker or counselor in a mental health specialty setting, or use of a mental health hotline), treatment in the general medical sector (a primary care doctor, other general medical doctor, nurse, or any other health professional not previously mentioned), and human services treatment (social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting or a religious or spiritual advisor). In the NCS-R the complementary and alternative medicine sector is defined as treatment from healers and self-help groups.

Sociodemographic predictor variables. Sociodemographic variables included age (age groups: 18–29, 30–44, 45–59, and 60 and above), gender, race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), marital status (married or cohabitating, previously married, or never married), number of completed years of education (0–15 and 16 and above), urbanicity, and family income. Family income was defined by multiples of the poverty line as either low (≤1.5 times), low-average (>1.5 to three times), high-average (more than three times to six times), and high (more than six times). Health insurance for treatment of mental disorders (yes or no) was also examined as a predictor of dropout.

Health service predictor variables. Respondents were classified by any lifetime mental health care utilization, including inpatient care, outpatient counseling or psychotherapy, or use of psychotropic medications. Number of different provider groups seen in the past 12 months for mental health treatment and treatment stage (measured by the number of visits at the time of dropout) were also examined as predictors.

Diagnostic predictor variables. In the NCS-R, DSM-IV ( 15 ) diagnoses were made with the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Version 3.0 ( 16 ), a fully structured, lay-administered diagnostic interview for the presence of any DSM-IV mood, anxiety, or substance use disorder and intermittent explosive disorder. A blind clinical reappraisal study that used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) ( 17 ) as the validation standard showed generally good concordance between DSM-IV CIDI and SCID diagnoses for anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders. The CIDI diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder was not validated.

Treatment dropout. For each treatment sector, respondents were asked whether they received treatment in the past 12 months and, if so, whether treatment had stopped or was ongoing. Respondents who stopped treatment in that sector were asked whether they "quit before the [provider(s) in that sector] wanted you to stop." Respondents who reported quitting before the provider or providers wanted them to stop were classified as having dropped out from that treatment sector. Respondents who reported 20 or more visits in the past 12 months in any single sector were classified as being stably in treatment whether or not they subsequently dropped out. A separate variable (overall dropout) denoted dropping out from all sectors. Because self-help groups have no providers, it was not possible to determine whether treatment stopped before the provider wanted. In addition, the number of respondents seeking treatment from healers in the past 12 months (N=62) was too small to analyze independently. Therefore, analyses of dropout predictors from the complementary-alternative medicine sector were not conducted, although adjunctive complementary-alternative treatment in the past 12 months was used as a predictor of dropout from other sectors.

Analysis procedures

NCS-R data were weighted to adjust for differences in selection probabilities, differential nonresponse, and residual differences on sociodemographic variables between the sample and the U.S. population. An additional weight was used for the part II sample to adjust for oversampling of part I cases ( 14 ). Twelve-month treatment episodes were aggregated into the four treatment sectors. Within each sector, basic patterns were examined of the median number and interquartile range of visits and the proportion of patients who had dropped out, completed, and were still in treatment. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to examine dropout by number of visits. Predictors of dropout were examined with discrete-time survival analysis. Separate models examined dropout after the first two visits versus later visits. Differences in predictors across sectors were examined with interaction terms between predictors and dummy variables for the sector. Standard errors were estimated with the SUDAAN ( 18 ) software system to adjust for clustering and weighting data. Multivariate significance tests were conducted with Wald χ2 tests based on coefficient variance-covariance matrices that were adjusted for design effects by use of the Taylor series method. Statistical significance was evaluated with two-sided design-based tests ( α =.05).

Results

Treatment within sectors

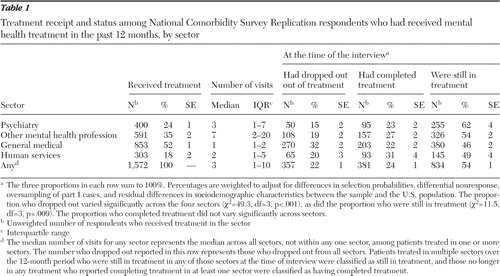

Of the 1,164 respondents who had received mental health treatment in the 12 months before the interview, approximately one-fifth (22.4%) dropped out of treatment. The general medical sector was the most common treatment sector, accounting for approximately half of treatment episodes ( Table 1 ). However, the longest treatment episodes, measured by average number of visits, were to other mental health professionals, followed by psychiatrists. A majority of respondents who had received services in the past 12 months were in treatment at the time of the interview. The proportion of patients who dropped out differed significantly across sectors, from 32% for the general medical sector, followed by 20% for human services, 19% for other mental health professionals, and 15% for psychiatrists ( Table 1 ).

|

The cumulative probability of dropout varied significantly across the four sectors ( Figure 1 ). Survival curves indicate that nearly 60% of patients eventually dropped out of treatment from the general medical sector. Among patients who dropped out, the median number of visits until dropout was four to six in the specialty mental health sector (psychiatrist or other mental health professional) and three in the general medical and human services sectors.

Dropout across sectors

In multivariable models pooled across sectors, elevated odds of dropout were significantly predicted by initial phase of treatment, absence of health insurance, provision of care in one or two sectors (versus three or four), not receiving complementary-alternative treatment, and treatment in the general medical sector ( Table 2 ). Treatment in the mental health specialty sector was associated with significantly reduced odds of dropout. [A version of Table 2 that includes the chi square test data is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

|

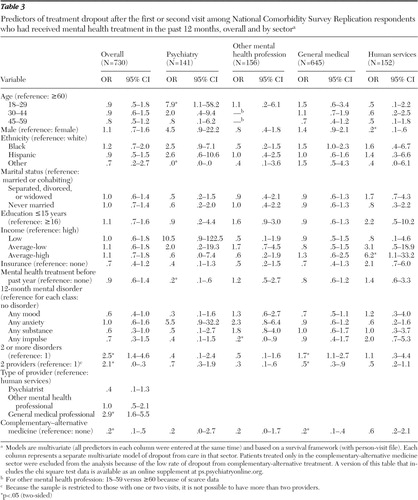

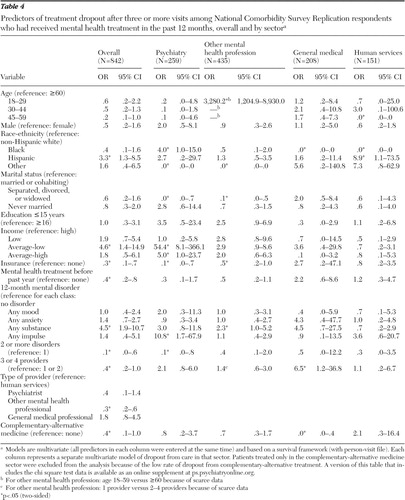

Dropout after the first or second visit was significantly associated with psychiatric comorbidity, care in only one sector, treatment in the general medical sector, and receipt of complementary-alternative treatment ( Table 3 ). Dropout after the third or later visit was significantly associated with Hispanic ethnicity, average-low income, substance use disorder, treatment in the general medical sector or human services sector, absence of health insurance, previous mental health treatment, and psychiatric comorbidity ( Table 4 ). [Versions of Tables 3 and 4 that include the chi square test data are available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

|

|

Several predictors differed significantly across sector or by timing of dropout, which required a disaggregated analysis of predictors separately in each sector for early and later phases of treatment ( Tables 2 – 4 ). The probability of treatment dropout in the general medical and mental health specialty sectors (nonpsychiatrists) was much higher after the first two visits than after subsequent visits.

Age. Younger age significantly predicted dropout among patients treated by psychiatrists, an association limited to dropout after the first two visits. There was also a suggestion of a nonlinear association of age with dropout after three or more visits to the human services sector, with highest odds of dropout among middle-aged patients.

Gender. Men were significantly less likely than women to leave treatment in the human services sector (odds ratio [OR]=.3) ( Table 2 ). This association was confined to the first two visits.

Race-ethnicity. Compared with non-Hispanic whites, patients in the ethnic group "other" were less likely to drop out of care provided by a psychiatrist, whereas non-Hispanic black patients were more likely to drop out, an association limited to dropout after the third visit. Although patients' race-ethnicity did not significantly predict dropout from treatment by other provider groups in the overall model, several associations between race-ethnicity and dropout were evident among patients who made at least three visits ( Table 4 ).

Marital status. Compared with patients who were previously married, those who were married or cohabiting had higher odds of dropout from the mental health specialty sector.

Income. Income had a nonlinear association with dropout from human services treatment, with the highest odds of dropout among patients with average-high incomes. Average-high (versus high) income predicted dropout from human services treatment only after the first two visits. Average-low income was associated with increased odds of dropout from care from a psychiatrist but only after three or more visits.

Education. Low education (15 years or less) was associated with elevated odds of dropout from treatment with mental health professionals other than psychiatrists (OR=1.9) but not from other sectors ( Table 2 ).

Mental health insurance. Mental health care insurance was significantly associated with low odds of dropout from treatment provided by a psychiatrist (OR=.3) and by other mental health professionals (OR=.5) but not from treatment from other sectors ( Table 2 ). Significant effects in the specialty sector, however, were confined to dropout after three or more visits.

Past mental health treatment. Any lifetime mental health treatment was significantly associated with low odds of dropout from care provided by a psychiatrist (OR=.3) ( Table 2 ) but not from care in other sectors, and this finding was limited to dropout after two or more visits (OR=.2) ( Table 3 ).

Mental disorders. Compared with patients who did not have a mental disorder, those with a substance use disorder were at significantly elevated risk of dropout from treatment provided by mental health professionals other than psychiatrists. This association was significant for patients with three or more visits. Impulse control disorder predicted dropout only from treatment provided by human services professionals. A comparison of patients with and without serious mental illnesses revealed no significant associations with dropout overall or from any of the individual sectors ( 19 ). (Results are available on request.) Given the large number of associations examined, this small number of individually significant associations could occur by chance.

Psychiatric comorbidity. Patients who met criteria for two or more classes of psychiatric disorders were at significantly elevated risk of dropout overall from care received in the general medical sector (OR=1.5) ( Table 2 ) and before the third visit (OR=1.7) ( Table 3 ). However, psychiatric comorbidity was associated with reduced dropout from treatment provided by a psychiatrist after three or more visits (OR=.1) ( Table 4 ).

Number of sectors in which treatment was obtained. A total of 26.6% of patients received care in more than one sector (data not shown). Among patients with three or more visits, receipt of care from three or four sectors was associated with elevated odds of dropout from care provided in the general medical sector (OR=6.5) ( Table 4 ).

Complementary-alternative medicine. Use of complementary-alternative medicine was associated with significantly reduced odds of treatment dropout from the general medical sector and from treatment provided by mental health professionals other than psychiatrists. These associations were limited to dropout after three or more visits, although the association for other mental health professionals in this subanalysis did not reach statistical significance. Complementary-alternative medicine was also associated with reduced odds of dropout from treatment in the general medical sector after three or more visits.

Discussion

The overall services dropout rate (22.4%) resembles previous national estimates for the United States (19%) ( 12 ) and Canada (17%–22%) ( 1 ). In Canada lower dropout was found from care provided by primary care physicians than from care by psychiatrists or psychologists ( 1 ). However, in this U.S. study, we found the highest dropout for the general medical sector. Compared with Americans, Canadians may have closer and more established relationships with their primary care providers. In the United States, the brevity of general medical visits ( 20 ) offers little opportunity to develop patient rapport, trust, and participation ( 21 ) and may contribute to risk of dropout. Although general medical care has traditionally been delivered by individual practitioners ( 22 ), newer models involve collaborations between general medical and mental health professionals ( 23 , 24 ). The finding of lower rates of dropout among patients receiving care from multiple sectors supports the potential of this approach.

We found that the first two visits are a period of high risk of dropout, especially in the general medical and nonpsychiatrist mental health sectors. The initial two visits are likely critical for patient engagement and diagnostic evaluation. A high risk of early dropout highlights the importance of understanding the consequences of dropout and of effective engagement in care ( 5 ).

Risk factors for dropout

The behavioral model of access to health care ( 25 ) offers one framework for organizing findings about client-level predictors of dropout. Under this framework, dropout risk can be viewed as a joint function of predisposing demographic factors (for example, gender and age) and social factors (for example, race-ethnicity, marital status, and education), enabling factors (for example, health insurance, income, and number of providers), and need (for example, psychiatric disorder, comorbidity, and past treatment). Below we review these factors, considering stage and sector of treatment.

In keeping with NCS data ( 12 ) and clinical research ( 7 ), patient gender was not significantly related to overall risk of treatment dropout. However, women were significantly more likely than men to drop out early from treatment in the human services sector. The reasons for this are unclear, although this finding might be related to lower levels of illness severity among women compared with men who are treated in this sector. This gender difference in early dropout persisted despite adjustment for number and type of mental disorders. Patient age also was not significantly associated with overall dropout, although young age was associated with increased risk of early dropout from care provided by a psychiatrist ( 12 ).

Aspects of social structure, including marital status, education, and race-ethnicity, had complex relationships with dropout risk. Compared with patients who were separated, divorced, or widowed, those who were married were significantly more likely to drop out from specialty mental health care later in treatment. This finding is in accord with evidence that spouses of patients receiving individual psychotherapy sometimes respond negatively to their partner's treatment ( 26 , 27 , 28 ). Alternatively, patients without partners may tend to become more dependent on their psychotherapist and more likely to comply with treatment recommendations ( 29 ).

Although education was not related to overall treatment dropout, 16 or more years of education was associated with a lower risk of dropout from care provided by mental health professionals other than psychiatrists. Acceptance ( 30 ), utilization ( 31 ), and completion ( 32 , 33 ) of psychotherapy have been directly linked to patients' level of education. Patients who have more education may also be more responsive to certain forms of psychotherapy ( 34 , 35 ).

Patient race-ethnicity had no overall association with odds of dropout. Non-Hispanic blacks, however, were significantly more likely than whites to drop out of care provided by a psychiatrist. Racial-ethnic differences in quality of mental health care ( 36 , 37 ) may contribute to racial-ethnic differences dropout.

Health insurance, higher income, and care coordination may enable service use and reduce dropout. The effect of health insurance in reducing dropout risk was evident after the first two visits, perhaps because having insurance lowers what otherwise would be mounting out-of-pocket treatment costs. The recent increase in uninsured Americans ( 38 ) may increase the risk of dropping out of specialty mental health treatment. Similarly, high-income patients were less likely than patients with low-average incomes to drop out ( 39 ), especially later in the course of care provided by a psychiatrist. Receiving mental health care from a larger number of provider sectors also reduced the probability of treatment dropout, but this could reflect a selection effect—more adherent or more assertive patients may be more apt to visit multiple sectors.

Use of complementary-alternative medicine was associated with a marked reduction in the odds of dropout from traditional mental health care services. These protective effects were greatest early in treatment. Self-help group attendance has been shown to enhance adherence to conventional mental health services ( 40 ). Participation in self-help groups and other forms of complementary-alternative medicine has also been found to increase appreciation or satisfaction with mental health services ( 41 ), which in turn may enhance retention in treatment ( 42 ). Self-help groups tend to be used as supplements rather than alternatives to traditional care ( 43 ). Our results raise the possibility that greater coordination of professional services with self-help and other complementary-alternative medicine services might help reduce dropout from professional care, a hypothesis that requires experimental evaluation.

Need—as measured by individual mental disorders, comorbid disorders, and past treatment—demonstrated complex relationships with risk of dropout. In the aggregate, substance use disorders were related to dropout after the first two visits, a finding consistent with reports of high dropout rates from specific substance abuse treatment programs ( 44 , 45 , 46 ) and low perceived need for such treatment ( 47 ). This is a particularly concerning finding, given that longer-term treatments tend to be more successful than brief treatments for substance use disorders ( 48 ).

Overall, mood and anxiety disorders appeared to exert little influence on the propensity to drop out, although dropout from treatment provided in the general medical sector was significantly lower among respondents with mood disorders than without them. In evaluating dropout risk, consideration should be given to factors beyond measured clinical symptoms. Concepts such as predisposition to use services and enabling resources that have been primarily studied as predictors of service use ( 25 ) may also guide assessment of treatment dropout risk.

Early in treatment, patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders were more likely than patients with one disorder to leave treatment delivered in the general medical sector, whereas later in treatment the reverse was true. General medical professionals likely have less experience managing patients with psychiatric comorbidities ( 10 , 49 ). Mismatches of clinical complexity and provider skill and resources may contribute to risk of treatment dropout.

Previous mental health treatment was linked to lower risk of dropout from care provided by a psychiatrist. This was observed early in such treatment and overall after two or more visits and is consistent with evidence that previous mental health service use tends to predict future use ( 50 ). Stigma or embarrassment, which can contribute to treatment refusal or dropout ( 51 ), may be more pronounced among new patients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, because psychiatric disorders, service use, and treatment dropout were retrospectively assessed by self-report, the results are subject to recall bias. In community surveys, distressed respondents may tend to overstate the number of visits to a care provider ( 52 ). Second, the duration of recommended treatment may vary between provider groups and among the providers within these groups, and patients' perceptions of providers' intentions introduce another level uncertainty. Third, treatment episodes were measured by number of visits. Provider groups may vary in the time between scheduled visits ( 53 ), and treatment duration may be more important than number of visits ( 54 ). Fourth, many potentially relevant patient characteristics (such as stigma, functional impairment, and satisfaction with treatment), professional characteristics (such as communication skills and clinical expertise), and service characteristics (such as copayments and environmental obstacles) were not examined. Fifth, the tendency of high service users to seek care from several sectors may explain their lower rate of dropout. Sixth, because a large number of comparisons were examined, some associations found to be significant may have occurred by chance. Seventh, the survey captured only visits from the most recent 12 months in what may have been long treatment episodes. However, because only 21% of all treatment episodes included more than 12 visits, it is unlikely that this truncation substantially influenced reported treatment dropout patterns. Finally, we were unable to account for aspects of care for the same episode occurring in the period before or after the 12-month reporting interval.

Conclusions

It may be fruitful to study treatment dropout in national surveys, an aspect of quality of care usually reserved for studies of clinical populations. The findings of this study highlight the importance of research to understand the clinical significance of dropout, especially for populations at high risk. Progress in this area will require a broadening of the concepts of treatment and dropout, to consider the value of services provided or discontinued across multiple, often uncoordinated sectors.

Several clinical strategies may reduce dropout ( 5 ), including appointment reminders ( 55 ), treatment contracts ( 56 ), case management ( 57 ), and patient education and activation ( 58 ). For example, communications from primary care physicians about medication treatment plans and education about side effects may reduce early treatment termination ( 59 ). Our findings help clarify which patients, at which stage of treatment, and in what sector may benefit most from such strategies to optimize treatment goals.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by grant U01-MH60220 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, grant 044780 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the John W. Alden Trust. Collaborating NCS-R investigators include Ronald C. Kessler, Ph.D. (principal investigator), Kathleen Merikangas, Ph.D. (coprincipal investigator), James Anthony, M.Sc., Ph.D., William Eaton, Ph.D., Meyer Glantz, Ph.D., Doreen Koretz, Ph.D., Jane McLeod, Ph.D., M.P.H., Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., Harold A. Pincus, M.D., Greg Simon, M.D., M.P.H., Michael Von Korff, Sc.D., Philip S. Wang, M.D., Dr.P.H., Kenneth Wells, M.D., M.P.H., Elaine Wethington, Ph.D., and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen, Ph.D. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations or agencies or the U.S. government. The NCS-R is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. The authors thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation and fieldwork and consultation on data analysis. The activities of the WMH Survey Initiative are supported by NIMH grant R01-MH070884; the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; the Pfizer Foundation; grants R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01-DA016558 from the U.S. Public Health Service; grant FIRCA R03-TW006481 from the Fogarty International Center; the Pan American Health Organization; Eli Lilly and Company; Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals; GlaxoSmithKline; and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Dr. Olfson has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company and AstraZeneca, has served as a consultant to Pfizer and AstraZeneca, and has served as a speaker for Janssen. Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, Kaiser Permanente, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly and Company and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has received research support for epidemiological studies from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Wang J: Mental health treatment dropout and its correlates in a general population sample. Medical Care 45:224–229, 2007Google Scholar

2. Wang PS, Gilman SE, Guardino M, et al: Initiation of and adherence to treatment for mental disorders: examination of patient advocate group members in 11 countries. Medical Care 38:926–936, 2000Google Scholar

3. Goldenberg V: Ranking the correlates of psychotherapy duration. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 29:201–214, 2002Google Scholar

4. Hatchett GT, Han K, Cooker PG: Predicting premature termination from counseling using the Butcher Treatment Planning Inventory. Assessment 9:156–163, 2002Google Scholar

5. Ogrodniczuk JS, Joyce AS, Piper WE: Strategies for reducing patient-initiated premature termination of psychotherapy. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 13:57–70, 2005Google Scholar

6. Hunt C, Andrews G: Drop-out rate as a performance indicator in psychotherapy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 85:275–278, 1992Google Scholar

7. Green CA, Polen MR, Dickinson DM, et al: Gender differences in predictors of initiation, retention, and completion in an HMO-based substance abuse treatment program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23:285–295, 2002Google Scholar

8. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, et al: Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance: characteristics and outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:160–165, 2000Google Scholar

9. Melartin TK, Rytsala HJ, Leskela US, et al: Continuity is the main challenge in treating major depressive disorder in psychiatric care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:220–227, 2005Google Scholar

10. Uebelacker LA, Wang PS, Berglund PA, et al: Clinical differences among patients treated for mental health problems in general medical and specialty mental health settings in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. General Hospital Psychiatry 28:387–395, 2006Google Scholar

11. Sturm R, Meredith LS, Wells KB: Provider choice and continuity for the treatment of depression. Medical Care 34:723–734, 1996Google Scholar

12. Edlund MJ, Wang PS, Berglund PA, et al: Dropping out of mental health treatment: patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:845–851, 2002Google Scholar

13. De Mello MF, Myczcowisk LM, Menezes PR: A randomized controlled trial comparing moclobemide and moclobemide plus interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of dysthymic disorder. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 10:117–123, 2001Google Scholar

14. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, et al: The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:69–92, 2004Google Scholar

15. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

16. Kessler RC, Ustun TB: The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:93–121, 2004Google Scholar

17. First MB, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

18. SUDAAN, Version 8.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 2002Google Scholar

19. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617–627, 2005Google Scholar

20. Hing E, Cherry DK, Woodwell BA: National Ambulatory Care Survey: 2004 summary. Advance Data 372:1–34, 2006Google Scholar

21. Gross DA, Zyzanski SJ, Borawski EA, et al: Patient satisfaction with time spent with their physician. Journal of Family Practice 47:133–137, 1998Google Scholar

22. Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, et al: Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ 327:1219–1221, 2003Google Scholar

23. Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al: Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1455–1462, 2004Google Scholar

24. Katon W, Unützer J: Collaborative care models for depression: time to move from evidence to practice. Archives of Internal Medicine 166:2304–2306, 2006Google Scholar

25. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

26. Roberts J: Perceptions of the significant other of the effects of psychodynamic psychotherapy: implications for thinking about psychodynamic and systemic approaches. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:87–93, 1996Google Scholar

27. Schwartz RS: Psychotherapy and social support: unsettling questions. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 13:272–279, 2005Google Scholar

28. Sandell R, Blomberg J, Lazar A, et al: Varieties of long-term outcome among patients in psychoanalysis and long-term psychotherapy: a review of findings in the Stockholm Outcome of Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy Project (STOPP). International Journal of Psychoanalysis 81:921–942, 2000Google Scholar

29. Bornstein RF: Dependency and patienthood. Journal of Clinical Psychology 49:397–406, 1993Google Scholar

30. Furnham A, Wardley Z: Lay theories of psychotherapy: I. attitudes toward, and beliefs about, psychotherapy and therapists. Journal of Clinical Psychology 46:878–890, 1990Google Scholar

31. Wei W, Sambamoorthi U, Olfson M, et al: Use of psychotherapy for depression in older adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:711–717, 2005Google Scholar

32. Howard KI, Cornille TA, Lyons JS, et al: Patterns of mental health service utilization. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:696–703, 1996Google Scholar

33. Nakao M, Fricchione G, Myers P, et al: Depression and education as predicting factors for completion of a behavioral medicine intervention in a mind/body medicine clinic. Behavioral Medicine 26:177–184, 2001Google Scholar

34. Schaefer BA, Koeter MW, Wouters L, et al: What patient characteristics make clinicians recommend brief treatment? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 107:188–196, 2003Google Scholar

35. Valbak K: Suitability for psychoanalytic psychotherapy: a review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109:164–178, 2004Google Scholar

36. Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, et al: Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:2027–2032, 2001Google Scholar

37. Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC: Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:284–292, 2000Google Scholar

38. Garson A Jr: The uninsured: problems, solutions, and the role of academic medicine. Academic Medicine 81:798–801, 2006Google Scholar

39. Weinick RM, Byron SC, Bierman AS: Who can't pay for health care? Journal of General Internal Medicine 20:504–509, 2005Google Scholar

40. Magura S, Laudet AB, Mahmood D, et al: Adherence to medication regimens and participation in dual-focus self-help groups. Psychiatric Services 53:310–316, 2002Google Scholar

41. Hodges JQ, Markward M, Keele C, et al: Use of self-help services and consumer satisfaction with professional mental health services. Psychiatric Services 54:1161–1163, 2003Google Scholar

42. Rossi A, Amaddeo F, Sandri M, et al: What happens to patients seen only once by psychiatric services? Psychiatry Research 157:53–65, 2008Google Scholar

43. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA 282: 651–651, 1999Google Scholar

44. Deren S, Goldstein MF, Des Jarlais DC, et al: Drug use, HIV-related risk behaviors and dropout status of new admissions and re-admissions to methadone treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 20:185–189, 2001Google Scholar

45. Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, et al: Methadone treatment practices and outcome for opiate addicts treated in drug clinics and in general practice: results from the National Treatment Outcome Research Study. British Journal of General Practice 49:31–34, 1999Google Scholar

46. McFarland BH, Deck DD, McCamant LE, et al: Outcomes for Medicaid clients with substance abuse problems before and after managed care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 32:351–367, 2005Google Scholar

47. Fiorentine R, Anglin MD: Perceiving need for drug treatment: a look at eight hypotheses. International Journal of Addiction 29:1835–1854, 1994Google Scholar

48. Moos RH: Addictive disorders in context: principles and puzzles of effective treatment and recovery. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 17:3–12, 2003Google Scholar

49. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115–123, 1999Google Scholar

50. Yokopenic PA, Clark VA, Aneshensel CS: Depression, problem recognition, and professional consultation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 171:15–23, 1983Google Scholar

51. Ben-Noun L: Characterization of patients refusing professional psychiatric treatment in a primary care clinic. Israeli Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences 33:167–174, 1996Google Scholar

52. Rhodes AE, Fung K: Self-reported use of mental health services versus administrative records: care to recall? International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:165–175, 2004Google Scholar

53. Fortney J, Rost K, Zhang M, et al: The impact of geographic accessibility on the intensity and quality of depression treatment. Medical Care 37:884–893, 1999Google Scholar

54. Ritsher JB, Moos RH, Finney JW: Relationship of treatment orientation and continuing care to remission among substance abuse patients. Psychiatric Services 53:595–601, 2002Google Scholar

55. Kitcheman J, Adams CE, Pervaiz A, et al: Does an encouraging letter encourage attendance at psychiatric out-patient clinics? The Leeds PROMPTS randomized study. Psychological Medicine 38:717–723, 2008Google Scholar

56. Sledge WH, Moras K, Hartley D, et al: Effect of time-limited psychotherapy on patient dropout rates. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:1341–1347, 1990Google Scholar

57. Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, et al: Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services 54:219–225, 2003Google Scholar

58. Brown JM, Miller WR: Impact of motivational interviewing on participation and outcome in residential alcoholism treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 7:211–218, 1993Google Scholar

59. Bull SA, Hu XH, Lee JY, et al: Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: influence of patient-physician communication. JAMA 288:1403–1409, 2002Google Scholar