Mental Health of Children of Low-Income Depressed Mothers: Influences of Parenting, Family Environment, and Raters

Depression is the most common psychiatric condition among mothers and is associated with significant psychiatric and functional problems for their children ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). Understanding the mechanisms by which these poor outcomes develop is critical for designing preventive interventions to reduce the impact of maternal depression on children. Genetic factors are likely to play a significant role ( 5 , 6 ), but the parenting and stressful family situations these children experience have also been shown to make substantial contributions to their mental health problems.

When mothers are depressed, they are less likely to have positive relationships and good communication with their children ( 7 , 8 ) or to engage in proactive discipline strategies ( 3 , 9 , 10 ). Moreover, the family environments of depressed parents are characterized by major stressful life events and conflict ( 11 , 12 ). They also have lower social support ( 13 ) and family cohesion ( 14 ) than families not affected by parental depression. These are critical factors known to lead to poor adjustment of children ( 3 , 15 , 16 ). Low-income families in urban environments are especially likely to experience major stressors associated with inadequate resources and unsafe communities ( 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ).

However, only a few studies have explicitly tested whether the quality of parenting and the family environment can explain the differences in children's behavior that are associated with maternal depression. Researchers who have studied mechanisms behind these differences have included as participant groups mothers with distress but without a diagnosis of major depressive disorder ( 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ) and have relied on depressed mothers' reports of child behavior, although these reports may be distorted by mothers' negative cognition ( 27 , 28 ).

In this study we investigated the association of maternal depression, parenting, and family stressors in a group of children aged four to ten whose functioning and problems were rated by their fathers, teachers, and mothers in a cross-sectional design. It involved a non-treatment-seeking sample of mothers who had diagnoses of major depressive disorder and a similar sample of mothers and children from the same low-income urban communities who had not experienced maternal depression. Data were collected in 2000–2003. Most mothers were African American or Latina. We hypothesized that children of mothers with depression would have more problems and worse functioning than their peers whose mothers did not have depression and that poor-quality parenting and low support and high stress within the family would account for these negative effects.

Methods

Participants

Mothers of four- to ten-year-old children who were participating in a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of depression treatments for low-income women from racial-ethnic minority groups ( 29 ) were eligible to participate in a substudy focusing on children. In the treatment study, 66% of eligible women who screened positive for depression participated. Of the 223 mothers who were eligible for the child study, 133 (60%) participated. Mothers gave written informed consent to participate with their four- to ten-year-old child, and children seven and older gave their assent. Two-thirds of the mothers had major depressive disorder, and the others were free of psychiatric disorder. There were no differences between those who did and did not participate, in terms of maternal age, ethnicity, number of children, child's age, child's gender, or, among the women with depression, their initial depression assessment score.

Half of the children had a biological father living in the home with the mother and child. For the others, a father or father figure was selected to be interviewed if the child saw him at least once per week, with the selection prioritized for whom to interview as follows: biological father not in the home; foster father, stepfather, or adoptive father in the home; stepfather or adoptive father not in the home; or the person the mother described as "most like a parent" to the child. This procedure yielded a father figure (hereafter referred to as "father") for 122 (92%) children. Of these, 111 (91%) mothers gave consent to contact the father for a phone interview, and 83 interviews with fathers (62% of sample) were completed. Among participating fathers, 62 (75%) lived in the home and 50 (60%) were biological fathers—rates that were not significantly different from those of the nonparticipating fathers. For the 118 children who attended school, interviews were completed with 89 (75%) of their teachers.

Measures

Maternal depression. Women were screened for depression with the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) ( 30 ), which has been validated as an effective method for identifying depression among primary care medical patients ( 31 , 32 ). Women who screened positive were assessed by trained lay interviewers with the Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) ( 33 ), a structured psychiatric interview that uses the criteria of the DSM-IV ( 34 ).

Sociodemographic characteristics. Mothers reported their age, ethnicity, education, marital and employment status, income, receipt of public income assistance, and their child's age, race-ethnicity, gender, and grade in school.

Children's emotional and behavioral problems and adaptive skills. Mothers, fathers, and teachers completed the appropriate version of the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) ( 35 ), which provides a parent report scale and teacher report scale for preschool-age children (ages four and five) and for children aged six through 11. The BASC is a set of conceptually based scales for rating child behavioral and emotional problems and social and adaptive functioning on a 4-point frequency scale. Results are reported as mean±SD T scores (T=50±10, range 0–100) that are age- and gender-normed based on a nationally representative sample. Both age versions of the parent and teacher report scales include two aggregate scales, the behavioral symptoms index (BSI) and the adaptive skills composite (ASC). The BSI is a measure of emotional and behavioral problems that combines the subscales of depression, anxiety, aggression, hyperactivity, attention problems, and atypicality. Higher BSI scores indicate more problems. The ASC measures social and adaptive functioning by combining the subscales of social skills, leadership, adaptive skills, and (from teachers only) study skills. Higher ASC scores indicate better functioning. The aggregate scales in both versions have excellent reliability, with internal consistency coefficients above .85 and retest reliability above .90 ( 35 , 36 ).

Composite measures of parenting and family environment. In order to provide a single robust, composite measure of parenting and of family environment, multiple scales completed by mothers were subject to principal-components analysis. For both constructs, the first factor was used as the composite measure, because it explained a large amount of the variance and adequately fit the data (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test of sampling adequacy=.58 and .73 for parenting and family environment, respectively). The two composite scales were standardized with z scores (z=0±1, range -3.0 to 3.0) and coded so that higher scores indicated more positive parenting and family environment.

The parenting quality composite included four variables: two subscales from the Children's Report of Parental Behavior Inventory ( 37 , 38 ), rejection (ten items; α =.72) and consistent discipline (eight items; α =.83), and two subscales from the Conflict Tactics Scales—Parent- Child version II ( 39 ), nonviolent discipline (four items; α =.76) and psychological aggression (five items; α =.77).

The family environment composite included five variables: stressful life events that the family had experienced in the previous year, adequacy of 15 resources assessed with the Family Resources Scale ( 40 ), family involvement based on the eight-item subscale from the parent report of the Child Health and Illness Profile—Child Edition ( 41 ), emotional and instrumental social support ( 42 ), and marital and relational conflict ( 42 ). Additional details on these composites are available from the first author.

Procedures

Recruitment was a multistage process involving screening for depression in more than 20 public health and social service settings and confirmation of the diagnosis by the CIDI structured interview. Eligible mothers were recruited into the child study by the staff of the treatment study ( 29 ). All procedures were approved by the relevant institutional review boards.

All mothers, with and without depression, completed a two- to three-hour interview in their home that was conducted by trained interviewers blind to mothers' depression and treatment status. Separate interviews with children lasted 45–90 minutes. Interviews were completed in Spanish, as needed, by bilingual interviewers. Interviews were completed an average of 7.8±5.0 weeks after mothers' identification for the treatment study, with 16 (19%) mothers in the depression group having a treatment visit at least one day before the baseline interview for the child study. No effects of beginning treatment before the baseline child study interview have been detected with the use of multiple analytic approaches.

Data analytic strategy

Multireporter, cross-situational assessments of children's behavior and social competence were obtained to reduce the bias of any one reporter, but the reports were too poorly correlated (range .21–.42) to simply combine them, a finding typical in the informant concordance literature ( 27 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ). Generalized estimating equation (GEE) methodology ( 48 ) was used to examine the extent to which mothers', fathers', and teachers' reports of each of the child outcomes were concordant. When reports were not concordant, linear regression models were fit that allowed the estimate of the association between child outcomes and independent variables to vary by rater, while appropriately taking into account the correlation of child outcomes across the three raters. Specifically, we estimated the association between the child outcomes (emotional and behavioral problems on the BASC BSI and adaptive skills on the BASC ASC) and maternal depression and sociodemographic control variables separately for each rater. Multivariate Wald statistics, appropriate with GEE methodology ( 49 ), were used to test whether the data supported the use of rater-specific associations for either maternal depression or for sociodemographic control variables. Simplified models were fit when associations were found not to vary across raters (Wald test p>.05), according to the mean of the associations for all raters. When associations varied by rater, we included rater-specific associations in the model. We then tested whether parenting and family environment characteristics mediated the association between maternal depression and children's outcomes by applying Baron and Kenny's ( 50 ) and Kenny and Kashy's ( 51 ) methodologies.

Results

The mean±SD age of mothers was 31.0±6.1. A total of 58 (44%) mothers were African American, 70 (53%) were Latina first-generation immigrants (52%), and five (4%) were Caucasian. Almost all were biological mothers (N=130; 98%). The 84 women in the depression group met criteria for current major depressive disorder on the CIDI ( 33 ); the 49 women in the comparison group had no current or past psychiatric disorders. Sixty (71%) of the mothers with depression had comorbid anxiety disorders, but mothers were excluded if they had bipolar disorder, active substance dependence, or psychotic disorder or were pregnant or breast-feeding ( 29 ). Depressed mothers reported a mean age of 25 years for onset of depression (range age seven to age 53), a mean of 4.5±4.9 lifetime episodes of major depression (range 1–25 episodes), and assessments of mild to moderate depression.

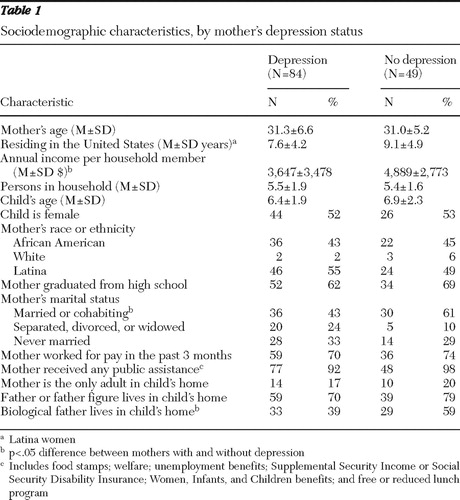

Children included 63 boys and 70 girls (age 6.6±2.1 years). Children with severe learning disabilities, mental retardation, or other developmental disabilities were excluded. Descriptive information on each subsample is given in Table 1 .

|

Mothers in the nondepressed group were more likely to be married, to have the child's biological father in the home, and to have families with slightly higher incomes ( Table 1 ). Only mothers' marital status and family income were used as control variables because having the biological father in the home was so highly correlated with marital status (r=.72, p<.001). Because nine mothers reported no monthly family income, we modeled income with two variables: a dichotomous variable of $0 versus any family income (labeled "zero income") and, among those reporting any income, a continuous measure of the natural log of annual income per household member (labeled "income level"). Child's age, gender, and race-ethnicity, although not significantly different between the groups, were also entered as controls. None of the associations between these control variables and the BASC scale scores varied according to the rater of the outcome.

Rater effects on association of depression with child outcome

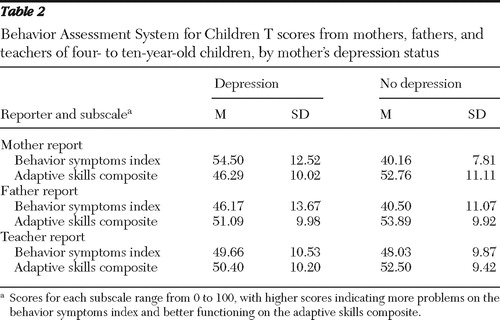

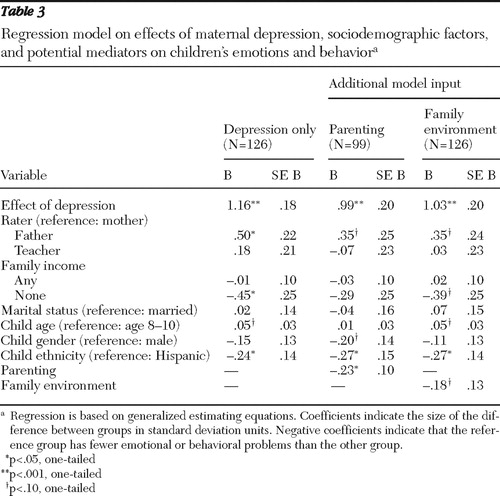

Table 2 provides the scores for the parent and teacher ratings on the BASC BSI and ASC scales by maternal depression group. The statistical significance of these differences by rater was examined with multivariate models ( Tables 3 and 4 ). Significant differences by rater were found in the associations between maternal depression and emotional and behavioral problems (Wald χ2 =21.87, df=2, p<.001). Although all raters reported more problems among children of mothers with depression than of those without depression, the difference between the groups was statistically significant only for mothers' reports (B=1.16 standard deviations, p<.001) and fathers' reports (B=.50 standard deviation, p<.05). Teacher-reported problems among the children of mothers with depression were only .18 standard deviation higher than problems of children of mothers without depression, and this difference was not statistically significant ( Table 3 ). Hispanic ethnicity and having no family income were also significantly related to lower levels of behavior problems. Younger children tended to have fewer problems (p<.10).

|

|

|

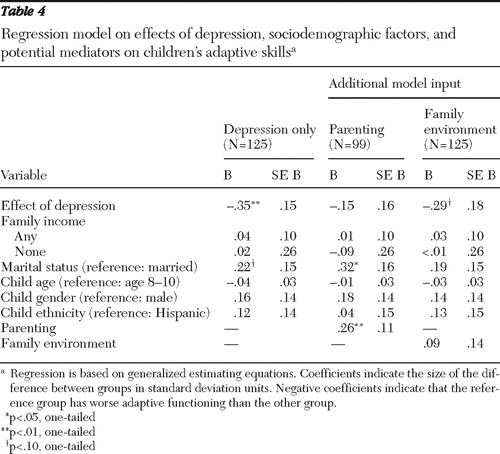

The association between maternal depression and children's adaptive skills did not differ by whether the rater was the mother, father, or teacher. All raters combined rated the children of mothers with depression as having statistically significantly lower adaptive skills by approximately one-third of a standard deviation (.35) than children of mothers without depression ( Table 4 ). In addition, children of married mothers were rated as having slightly higher levels of adaptive skills.

Potential mediators between depression and child outcomes

With the first criterion met for mediation—that of a significant relationship between the independent and the dependent variables—regression analyses were conducted to determine whether maternal depression was significantly related to the potential mediators in the presence of control variables, the second criterion for mediation ( 50 ). Maternal depression status was significantly related to both parenting quality (t=4.56, df=2, p<.001; effect size=–.86, 95% confidence interval [CI]=-.90 to –.36) and family environments (t=7.43, df=2, p<.001; effect size=-1.23, CI=–1.07 to –.67), indicating that both variables could be examined as potential mediators.

The third step in testing for mediation was carried out by adding parenting to the GEE models described above in which the children's outcomes were regressed on maternal depression status and sociodemographic control variables. More positive, less punitive parenting was associated with significantly fewer emotional and behavioral problems ( Table 3 , B=–.23, p<.05). Furthermore, mothers' parenting quality appeared to mediate partially the association between maternal depression and children's behavioral problems, as reported by both mothers and fathers, because once parenting entered the model, the coefficient for maternal depression was reduced by the same magnitude (approximately .15 standard deviation) for reports by both mothers and fathers and became only marginally significant for fathers. Teacher-rated differences remained nonsignificant.

When parenting was added to the regression model for children's adaptive skills, the association of maternal depression with children's adaptive skills was greatly reduced and no longer statistically significant ( Table 4 ); the difference between adaptive skills of children of mothers with depression versus those without depression was reduced from –.35 to –.15 standard deviation on the BASC ASC. Thus parenting quality fully accounted for the relationship between maternal depression and children's adaptive skills and acted as a mediator between them.

Family environment was not a significant predictor of children's emotional and behavioral problems or adaptive skills, when maternal depression was controlled in the models. This eliminated the possibility that this variable was a mediator between maternal depression and child outcomes ( Tables 3 and 4 ).

Discussion

This study extends prior research in several ways. First, the application of GEE allowed us to use data from multiple raters, allowed sample sizes to vary by rater, controlled for rater effects when they existed, and demonstrated the pervasive extent of problems in functioning, emotions, and behaviors among the children of depressed mothers compared with similar children from low-income and primarily minority families whose mothers were not depressed. Findings showed that fathers reported a moderate effect of maternal depression on children's emotional and behavioral problems (.50 standard deviation difference between groups), that the effect (difference between groups with and without maternal depression) according to mothers was much larger (1.16 standard deviations), and that teacher-reported differences between the depression groups in regard to children's emotional and behavioral problems were nonsignificant. Quantifying these rater differences in emotional and behavioral problems helps to inform the literature about cognitive bias associated with maternal depression ( 27 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ) by highlighting the degree to which the perspectives of different raters differed. Also important in terms of measurement is that all raters observed similar levels of impaired adaptive functioning for children of depressed versus not depressed mothers—even teachers who did not observe differences in emotional or behavioral problems.

Second, we extended prior research indicating that parenting that lacks warmth, is inconsistent, and involves harsh discipline may be an important mechanism by which maternal depression is associated with children's emotional and behavioral problems and poor adaptive skills. The latter finding is consistent with prior longitudinal research using nonclinical but low-income samples ( 23 , 24 ). The fact that mediation was observed for fathers' reports of child problems and functioning is particularly informative, adding an independent, potentially more objective outcome assessment than that of mothers who were depressed. Contrary to our hypotheses, family environment was not a mediator of these associations, primarily because it was not associated with the outcome variables once maternal depression was controlled for.

Despite large and statistically significant differences between the children of mothers with and without depression, the average BASC BSI and ASC scores were not in the clinical range for either group. Only about a fourth of the children of depressed mothers had scores in the clinical range, and less than 10% (N=3) of them had received any mental health services. The young age of this cohort may explain why their problems were not as severe as those typically observed in studies with older children of depressed mothers ( 3 , 15 , 16 ). As would be expected from the low number who showed a clinically defined need for services, less than 10% (N=3) of the children of depressed mothers and none of the children of nondepressed mothers had received any mental health treatment. Although Hispanic children had fewer behavior problems overall, separate analyses have demonstrated that the basic effect of maternal depression did not vary by ethnicity in that both Hispanic and African-American children of mothers with depression had significantly more problems than their peers whose mothers were not depressed.

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting these results. First, cross-sectional evidence of mediation by parenting is only the first step in demonstrating a possible causal pathway. Longitudinal analyses are needed to confirm the mediating pathways between maternal depression and child outcomes. Participant recruitment was an anticipated and significant difficulty, because the very characteristics that make the lives of these mothers and families important to understand also create challenges to involving them in research. Consequently, in both the women's treatment study and this study of children, approximately one-third of eligible participants did not complete data collection, largely because of difficulty in contacting them. Furthermore, sample sizes varied depending on the reporter of the measures, and many mothers were interviewed later than planned. Finally, a few mothers had their first treatment appointment—and a few others knew their treatment assignment—before their child study interview, so expectations regarding treatment may have influenced their ratings. However, we have not been able to detect any evidence of this effect. Further longitudinal analyses with this sample will explore the extent to which children's behavior and functioning improves when mothers' depression is treated, as well as whether their need for mental health services increases over time when maternal depression does not remit.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that the behavioral, emotional, and functional problems of children of depressed mothers living in low-income, high-risk urban environments are significantly greater than those of similar children whose mothers do not have depression. These differences in outcomes were observed by mothers, fathers, and teachers, despite important distinctions in their perceptions. The multi-informant, cross-situational nature of the data about children's problems and adaptive functioning and our ability to control for rater effects enhanced the strength of the finding that the associations with maternal depression were likely to be mediated through the quality of mothers' parenting. We did not find that the family environment made an independent contribution to poor child outcomes. This may be partly attributable to the specific stressors and strengths in the composite measure. But the lack of effect may be due to having a comparison group of low-income, minority families who are also affected by factors associated with poverty and discrimination, although not those unique to maternal depression.

Depression is most common in low-income, racial-ethnic minority, urban families ( 52 , 53 ), and the results of this study indicate that depression appears to confer a level of risk for children over and above that of poverty. It is worth noting that although children of mothers with depression had significantly more problems than children of mothers without depression, and approximately a quarter had clinically severe problems, most children's problems were not in the clinical range on the problem scales. This finding suggests that some children and their families are more able to cope, at least during childhood, with the stressors associated with maternal depression. Nonetheless, such early problems often increase the likelihood of significant emotional and physical health problems for children later in life ( 54 , 55 ), highlighting the importance of developing policies and practices to address the health services needs of these children and families ( 8 , 56 ).

Ensuring effective treatment for depressed mothers is critical ( 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ). However, these results indicate that family-level services are likely to also be necessary, consistent with theoretical models ( 3 , 9 , 56 , 60 ). It is important to translate promising new family interventions ( 56 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 ) into routine services designed to enhance parenting in families affected by maternal depression. To produce an impact, these interventions will have to not only be effective but also accessible. Adequate mechanisms for reimbursing family intervention services will be needed in order to stimulate the development and adoption of such services. Enhancing the opportunities for intervening with families affected by maternal depression is one important avenue for addressing the multiple needs of these children and their families and may to help reduce the distress and problems they often experience.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grants MH-58384 to Dr. Riley and MH-56864 to Dr. Miranda from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank the families and many clinic staff who participated in this project and acknowledge the analytic assistance of Maureen Keefer, Judy Robertson, and Carrie Mills. This work was not conducted as part of Dr. Broitman's official duties as a U.S. government employee.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Cummings EM, Davies PT: Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 35:73–112, 1994Google Scholar

2. Downey G, Coyne JC: Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin 108:50–76, 1990Google Scholar

3. Goodman SH, Gotlib IH: Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review 106:458–490, 1999Google Scholar

4. Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al: Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA 295:1389–1398, 2006Google Scholar

5. Kendler KS: Twin studies of psychiatric illness: an update. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:1005–1014, 2001Google Scholar

6. Rice F, Harold GT: Assessing the effects of age, sex and shared environment on the genetic aetiology of depression in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 43:1039–1051, 2002Google Scholar

7. Bosquet M, Egeland B: Associations among maternal depressive symptomatology, state of mind and parent and child behaviors: implications for attachment-based interventions. Attachment and Human Development 3:173–199, 2001Google Scholar

8. Lyons-Ruth K, Wolfe R: Depression and the parenting of young children: making the case for early preventive mental health services. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8:148–153, 2000Google Scholar

9. Hammen C: The social context of risk and resilience in children of depressed mothers, in Depression Runs in Families: The Social Context of Risk and Resilience in Children of Depressed Mothers. Edited by Hammen C. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1991Google Scholar

10. Kochanska G, Kuczynski L: Resolutions of control episodes between well and affectively ill mothers and their young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 15:441–456, 1987Google Scholar

11. Joiner T, Coyne JC: The Interactional Nature of Depression: Advances in Interpersonal Approaches. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1999Google Scholar

12. Hops H, Biglan A: Home observations of family interactions of depressed women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55:341–346, 1987Google Scholar

13. Barnett PA, Gotlib IH: Psychosocial functioning and depression: distinguishing among antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychological Bulletin 104:97–126, 1988Google Scholar

14. Billings AG, Moos RH: Coping, stress, and social resources among adults with unipolar depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 46:877–891, 1984Google Scholar

15. Hammen C: Context of stress in families of children with depressed parents, in Children of Depressed Parents: Mechanisms of Risk and Implications for Treatment. Edited by Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2002Google Scholar

16. Du Rocher Schudlich TD, Cummings EM: Parental dysphoria and children's internalizing symptoms: marital conflict styles as mediators of risk. Child Development 74:1663–1681, 2003Google Scholar

17. Albright M, Tamis-LeMonda C: Maternal depressive symptoms in relation to dimensions of parenting in low-income mothers. Applied Developmental Science 6:24–34, 2002Google Scholar

18. Puig-Antich JJ, Kaufman J: The psychosocial functioning and family environment of depressed adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32:244–253, 1993Google Scholar

19. O'Connor TG, Dunn J: Family settings and children's adjustment: differential adjustment within and across families. British Journal of Psychiatry 179:110–115, 2001Google Scholar

20. Olson SL, Kieschnick E: Socioenvironmental and individual correlates of psychological adjustment in low-income single mothers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 64:317–331, 1994Google Scholar

21. Garbarino J: The stress of being a poor child in America. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 7:105–119, 1998Google Scholar

22. Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ: The effects of poverty on children. Future Child 7:55–71, 1997Google Scholar

23. Bifulco A, Moran PM: Childhood adversity, parental vulnerability and disorder: examining inter-generational transmission of risk. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 43:1075–1086, 2002Google Scholar

24. Burt KB, Van Dulmen MH, Carlavati J, et al: Mediating links between maternal depression and offspring psychopathology: the importance of independent data. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46:490–499, 2005Google Scholar

25. Harnish, JD, Dodge KA, Valente E: Mother-child interaction quality as a partial mediator of the roles of maternal depressive symptomatology and socioeconomic status in the development of child behavior problems: Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Child Development 66:739–753, 1995Google Scholar

26. McCarty CA, McMahon RJ: Mediators of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing and disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Family Psychology 17:545–556, 2003Google Scholar

27. Chilcoat HD, Breslau N: Does psychiatric history bias mothers' reports? An application of a new analytic approach. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:971–979, 1997Google Scholar

28. Treutler CM, Epkins CC: Are discrepancies among child, mother, and father reports on children's behavior related to parents' psychological symptoms and aspects of parent-child relationships? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 31:13–27, 2003Google Scholar

29. Miranda JJ, Chung Y, Green BL, et al: Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:57–65, 2003Google Scholar

30. Spitzer RL, Williams JB: Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 272:1749–1756, 1994Google Scholar

31. Spitzer RL, Wakefield JC: DSM-IV diagnostic criterion for clinical significance: does it help solve the false positives problem? American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1856–1864, 1999Google Scholar

32. Spitzer RL, Williams JB: Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 183:759–769, 2000Google Scholar

33. Composite International Diagnostic Interview: Computer Program Version 2.1 Geneva, World Health Organization, 1998Google Scholar

34. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (Primary Care Version). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1995Google Scholar

35. Reynolds C, Kamphaus R: Behavior Assessment System for Children Manual. Circle Pines, Minn, American Guidance Service, 1992Google Scholar

36. Doyle A, Ostrander R: Convergent and criterion-related validity of the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Parent Rating Scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 26:276–284, 1997Google Scholar

37. Schaefer ES: Children's reports of parental behavior: an inventory. Child Development 36:413–424, 1965Google Scholar

38. Wolchik SA, Wilcox KL: Maternal acceptance and consistency of discipline as buffers of divorce stressors on children's psychological adjustment problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 28:87–102, 2000Google Scholar

39. Straus MA, Hamby SL: Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect 22:249–270, 1998Google Scholar

40. Dunst CJ, Leet HE: Measuring the adequacy of resources in households with young children. Child Care, Health and Development 13:111–125, 1987Google Scholar

41. Riley AW, Forrest CB, Starfield B, et al: The Parent Report Form of the CHIP-Child Edition: reliability and validity. Medical Care 42:210–220, 2004Google Scholar

42. Bassuk EL, Weinreb LF: The characteristics and needs of sheltered homeless and low-income housed mothers. JAMA 276: 640–646, 1996Google Scholar

43. Renk K, Phares V: Cross-informant ratings of social competence in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review 24: 239–254, 2004Google Scholar

44. Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH: Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin 101:213–232, 1987Google Scholar

45. Cai, X, Kaiser AP: Parent and teacher agreement on Child Behavior Checklist items in a sample of preschoolers from low-income and predominantly African American families. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 33:303–312, 2004Google Scholar

46. Duhig AM, Renk K: Interparental agreement on internalizing, externalizing, and total behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 7:435–453, 2000Google Scholar

47. Sawyer MG, Streiner DL: The influence of distress on mothers' and fathers' reports of childhood emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 26:407–414, 1998Google Scholar

48. Liang K-Y, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73:13–22, 1986Google Scholar

49. Rotnitzky A, Jewell NP: Hypothesis testing of regression parameters in semiparametric generalized linear models for cluster correlated data. Biometrika 77:485–497, 1990Google Scholar

50. Baron RM, Kenny DA: The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51:1173–1182, 1986Google Scholar

51. Kenny DA, Kashy DA: Data analysis in social psychology, in The Handbook of Social Psychology. Boston, McGraw-Hill, 1998Google Scholar

52. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Google Scholar

53. Williams DR, Gonzalez HM: Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:305–315, 2007Google Scholar

54. Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE: Risky families: social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin 128:330–366, 2002Google Scholar

55. Forrest CB, Riley AW: Childhood origins of adult health: a basis for life course health policy. Health Affairs 23(5):155–164, 2004Google Scholar

56. Riley AW, Valdez CR, Barrueco S, et al: Development of a family-based program to reduce risk and promote resilience among families affected by maternal depression: theoretical basis and program description. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 11:12–29, 2008Google Scholar

57. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

58. Miranda J, Azocar F: Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services 54:219–225, 2003Google Scholar

59. Miranda J, Duan N: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research 38:613–630, 2003Google Scholar

60. Beardslee WR, Gladstone TR: A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics 112:e119–e131, 2003Google Scholar

61. Sanford M, Byrne C: A pilot study of a parent-education group for families affected by depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 48:78–86, 2003Google Scholar

62. Boyd RC, Diamond GS: Developing a family-based depression prevention program in urban community mental health clinics: a qualitative investigation. Family Process 45:187–203, 2006Google Scholar

63. Sanders MR, McFarland M: Treatment of depressed mothers with disruptive children: a controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioral family intervention. Behavior Therapy 31:89–112, 2000Google Scholar