Psychotropic Medication Nonadherence Among United States Latinos: A Comprehensive Literature Review

Medication nonadherence among patients with psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression, is a major barrier to favorable treatment outcomes. Suboptimal adherence to psychotropic medications for these disorders has been associated with relapse, significantly more psychiatric hospitalizations and emergency room visits, poorer mental functioning, lower life satisfaction, more disability-related absences from work, greater substance use, increased suicidal behavior, poorer adherence to medications for comorbid medical conditions, and higher health care costs ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ).

Unfortunately, nonadherence to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers is common; previous literature reviews have noted rates ranging from 10% to 77%, with mean rates of 35%–60% ( 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). Previous studies have established risk factors for nonadherence, including limited insight, a negative attitude or subjective response toward medication, a shorter duration of illness, comorbid substance abuse, a poor therapeutic alliance, living alone, more self-reported side effects, and limited family support ( 18 , 19 , 20 ). However, many previous studies were significantly limited because they were conducted with predominantly Euro-American populations. Ethnic and racial disparities in adherence have been noted; nonwhite patients have been found to be more likely to have lower adherence ( 3 , 21 , 22 , 23 ).

Latinos are the largest and most rapidly growing minority group in the United States, constituting just over 13% of the population ( 24 ). More than 40% are foreign-born, and 75% are immigrants or children of immigrants ( 25 ). Acculturation, "the process by which individuals adopt the attitudes, values, customs, beliefs, and behaviors of another culture" ( 26 ), has been found to have mixed health effects for Latinos, including mental health effects ( 27 , 28 , 29 ). Prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders are lower among Latinos who are less acculturated, but those who have a disorder are less likely to receive mental health treatment ( 30 , 31 ). Given these health and acculturation relationships, acculturation could potentially affect adherence via, for example, physician-patient communication or health literacy. Ethnic differences have been previously noted for Latinos in the number and use of prescriptions for psychotropics ( 32 , 33 ), psychotropic dosing needs ( 34 ), response to psychotropics ( 35 ), and their tolerability for Latinos ( 36 , 37 ).

However, to our knowledge, there has not yet been a comprehensive review of the literature examining psychotropic adherence among Latinos living in the United States that includes the frequency of nonadherence, factors associated with it, and influences of language and acculturation on nonadherence. Our objectives were to assess the rate of nonadherence to psychotropic medications among Latinos living in the United States, compare the rate with those for other ethnic minority groups and Euro-Americans, and identify any culturally relevant factors that influence adherence among Latinos.

Methods

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases using combinations of the following keywords: antipsychotic, mood stabilizer, antidepressant, lithium, neuroleptic, psychotropic, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, adherence, compliance, Latino, Hispanic, ethnicity, Spanish language, and acculturation. We searched for articles published since 1980 that reported studies that measured prevalence of adherence to antipsychotics, antidepressants, or mood stabilizers among Latino adults in the United States. Reference lists from recent reviews ( 18 , 19 , 20 , 38 , 39 ) were also examined, as were bibliographies from all potentially relevant articles.

Study selection

We identified 518 papers in the searches. One of the authors (NML) then read every title and identified 214 potentially relevant articles. During this screening, broad inclusion criteria were used, but we excluded studies that examined adherence among patients who had only nonpsychiatric illnesses or that focused on nonpsychiatric medications only (for example, adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-AIDS). Also excluded were articles not in English or Spanish and articles that reported studies of pediatric populations only or studies conducted outside the United States. A search of the Spanish-language literature revealed no potentially relevant studies because all were conducted with populations outside the United States.

The 214 potentially relevant articles were read in detail by one of the authors. To be included, studies had to be of U.S. populations (including people living in Puerto Rico, although no studies of psychotropic medication adherence included this population), had to be in English or Spanish (no studies were in Spanish), had to include Latinos, and had to measure adherence and nonadherence (including self-report and medication discontinuation rates) to antidepressants, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers prescribed for depression, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder (even if adherence was not the primary focus of the study). Studies also had to examine ethnicity as a variable related to adherence or report adherence rates of all ethnic groups in the studies (so that we could determine whether there were significant differences between ethnic groups), or for studies that included only Latino participants, the studies had to examine adherence and factors influencing adherence.

We excluded studies if they did not measure separate adherence rates for Latinos; included only children and adolescents; examined medication adherence only for medications that were not antidepressants, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers; and examined adherence to antidepressants, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers that were prescribed for diseases other than those listed above (for example, we excluded studies of anxiety and dementia). Studies were also excluded if only study dropout rates were reported, rather than medication discontinuation or adherence rates, because many factors that cause study dropout do not necessarily cause nonadherence. This criterion led to our exclusion of a widely cited study that found that Latinos were more likely than Euro-Americans to drop out of a clinical trial and that identified the reasons for study discontinuation ( 36 ).

Data extraction

Of the 214 initially identified articles, 193 were excluded and 21 were included in our final analysis ( 1 , 6 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ). The results from one study were reported in two different articles ( 52 , 53 ), and we counted the articles as one study. One included study ( 44 ) examined adherence-related factors in a subset of a sample in another study ( 43 ), and we counted these as one study and used the nonadherence rate reported for the larger sample ( 43 ) in our calculation of the mean nonadherence rate for studies including only Latinos. For each of the 21 studies, two authors (NML and DPF) examined the study design and objectives, the location and patient population, medications studied, participant characteristics (including preferred language of participants and providers, if reported), measures of adherence, rates of adherence overall and by race-ethnicity, associations between race-ethnicity and adherence (including statistical measures), and any other adherence-relevant factors identified. For consistency, we use the terms "adherence" and "nonadherence" throughout this review, replacing the terms "compliance" and "noncompliance," which were used in some studies.

Calculation of nonadherence rates

For standardization, if studies reported adherence rates, we calculated nonadherence rates and report those. Most studies examined only adherence and nonadherence. Therefore, for studies that provided information on additional categories of adherence, such as for persons who were partially adherent or those who were excess fillers (those who filled prescriptions more frequently than expected) ( 6 , 40 , 58 , 59 , 60 ), we report all the rates that were provided ( Table 1 ); however, for mean nonadherence rate calculations, we used the summed partial adherence, nonadherence, and excess filler rates as the nonadherence rate. One article ( 40 ) reported separate adherence rates by ethnicity and diagnosis, and for this article, we give the separate rates ( Table 1 ); however, for calculating mean nonadherence rates, we averaged the nonadherence rates of the patients with different diagnoses within each ethnic group.

|

Although no measure of medication adherence is ideal, some measures have demonstrated more reliability than others. Patient and caregiver reports and physician reports of adherence have been shown to underestimate adherence ( 61 , 62 ), whereas adherence calculated by use of medication event monitoring system (MEMS) caps (electronic bottle caps) and from pharmacy fill records (for example, medication possession ratios [MPRs] and cumulative possession ratios [CPRs]) have been shown to be generally more objective measures ( 3 , 62 ). Therefore, we also separately analyzed the 11 articles that reported studies that used these typically more objective measures ( 1 , 6 , 46 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 60 ).

Data analysis and statistics

For studies in which comparison data were available but the investigators did not compare adherence rates of separate racial or ethnic groups, we used chi square tests to test the significance of differences in adherence rates by group. We performed such secondary calculations for 11 studies: nonadherence percentage calculations for three studies ( 51 , 55 , 56 ), chi square tests for two studies ( 50 , 57 ), and both percentage calculations and chi square tests for six studies ( 1 , 40 , 47 , 49 , 58 , 60 ). For the two studies in which the unadjusted and adjusted nonadherence rates yielded conflicting results ( 55 , 56 ), we included both findings but used the results of the multivariate analysis when comparing rates between racial or ethnic groups.

We used two methods to compare nonadherence rates between racial or ethnic groups. First, we examined the mean nonadherence rates across studies, which included calculating an effect size of the difference between the rates for Latinos and Euro-Americans. Second, we counted the number of studies that compared rates among groups, and we report how many of the studies did and did not find significant differences. To calculate the effect size, we used SPSS version 12.0.1 to pool the nonweighted nonadherence means and standard deviations across the studies and then used an online effect size calculator ( web.uccs.edu/lbecker/Psy590/escalc3.htm ). We used online chi square calculators ( www.graphpad.com and www.quantpsy.org ) for chi square calculations, and we used SPSS version 12.0.1 for descriptive statistics.

Racial and ethnic group terminology

The terminology for racial and ethnic groups in the literature is highly varied. For the purposes of this review, the term "U.S. Latino" includes anyone residing in the United States, including Puerto Rico, who has Mexican, Central American, South American, Puerto Rican, or Cuban ancestry. We use the terms "African American" to refer to U.S. residents who trace their ancestry to Africa and "Euro-American" for U.S. residents with European ancestry. For studies that used "Hispanic," "black," or "Caucasian," we have replaced these terms with "Latino," "African American," and "Euro-American," respectively, for standardization. If country of origin of the participants was specified in a study, we include that information. We understand that these definitions have limitations in that they group people from highly diverse backgrounds. Very few studies reported separate adherence rates for Asian Americans or other racial or ethnic groups, and the number of Asian-American patients or patients from other groups in those studies was typically very small, so we were unable to compare nonadherence rates or risk factors for Latinos and those groups.

Results

Description of studies and prevalence of nonadherence

The 21 studies ( Tables 1 and 2 ) that met inclusion criteria ( 1 , 6 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ) showed great heterogeneity in terms of study design and objectives and of population studied. Table 1 shows the four investigations that had only Latino participants, and Table 2 shows the 17 studies that included Latinos and other ethnic groups.

|

In terms of study design, 13 studies were prospective and eight retrospective. Study objectives varied; some studies focused specifically on adherence ( 1 , 6 , 41 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 49 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ), and others addressed different questions but measured adherence as part of their procedures. Eight studies were based in California ( 6 , 42 , 43 , 47 , 48 , 50 , 54 , 55 ), two in Texas ( 41 , 51 ), one in New Mexico ( 52 ), one in New York ( 49 ), one in Connecticut ( 56 ), and one in Ohio ( 40 ). Four studies were from National Registries of the Veteran's Health Administration ( 46 , 58 , 59 , 60 ), and three were national studies ( 1 , 45 , 57 ).

Twelve studies investigated nonadherence to antipsychotics ( 1 , 6 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 54 , 58 , 59 ), five examined antidepressants ( 45 , 47 , 52 , 55 , 57 ), two examined mood stabilizers ( 48 , 60 ), and two examined a combination of these medications ( 40 , 56 ). Ten studies focused on schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder ( 1 , 6 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 59 ), five focused on depression ( 45 , 47 , 52 , 55 , 57 ), three focused on bipolar disorder ( 48 , 58 , 60 ), and three involved a combination of these diagnoses ( 40 , 54 , 56 ).

The total sample size in the 21 studies ranged from 40 to 44,637 (mean±SD=6,024±13,268). Of the 17 studies that included both Latinos and other racial or ethnic groups, the percentage of Latino participants ranged from 2.9% to 56% (mean=20.3%±19.5%). Of the seven studies that reported preferred language, the proportion of Spanish-speaking participants ranged from none to 100% (mean=45.7%±35.0%). For seven studies, country of origin or ancestry of Latino participants was reported, which was primarily Mexico in four studies ( 41 , 43 , 50 , 51 ), primarily Puerto Rico in two ( 40 , 56 ), and a mix of Mexico, Guatemala, and El Salvador in one ( 42 ).

Studies used a range of adherence measures, including patient report ( 50 , 55 ), chart review or physician report ( 41 ), a combination of patient and family report and chart review ( 43 , 49 ), medication discontinuation (by patient report) ( 45 , 47 , 57 ), pill counts of returned pills ( 46 ), MEMS caps ( 56 ), calculations from pharmacy records (including cumulative mean gap ratio [CMGR], MPR, and CPR) ( 1 , 6 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 60 ), and urine testing for metabolites ( 54 ). Two studies did not describe the adherence measure ( 40 , 42 ). Nineteen studies reported the time period during which adherence was examined, which ranged from one week to 48 months (mean=10.2±10.3 months).

Nonadherence rates

Three of the four studies that included only Latinos ( 41 , 43 , 45 ) ( Table 1 ) reported nonadherence rates, which ranged from 33.0% to 55.0% (mean=44.0%±11.0%). The fourth ( 42 ) explored risk factors for nonadherence among Latinos but did not detail rates, and it is discussed below. Of the 17 studies that included Latinos and other racial or ethnic groups ( Table 2 ), 12 ( 1 , 6 , 40 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 60 ) provided data allowing comparison of nonadherence rates between Latinos and Euro-Americans. The mean nonadherence rates for Latinos and Euro-Americans were 39.4%±15.7% and 29.2%±16.5%, respectively, yielding an overall effect size of .64.

Ten of these studies also had data available for African Americans ( 1 , 6 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 60 ), and nonadherence rates in those studies were as follows: Latinos, range of 17.2%–63.1%, (mean=41.0%±16.3%); Euro-Americans, range of 10.0%–57.2% (mean=31.3%±17.2%), and African Americans, range of 22.7%–65.1% (mean=43.2%±16.9%). Only one study reported separate rates by ethnicity and diagnosis ( 40 ); it showed no difference between nonadherence rates for Latinos with schizophrenia compared with Euro-Americans with schizophrenia and a nonsignificant trend (p=.055) toward higher nonadherence rates among Latinos compared with Euro-Americans for patients with depression.

Comparison of rates for racial or ethnic groups

Sixteen studies evaluated differences in nonadherence rates between Latinos and Euro-Americans. (In addition to the 12 studies that reported nonadherence rates for Latinos and Euro-Americans, four studies measured and compared nonadherence rates in the two groups but did not provide details.) Of these 16 studies, six found no statistically significant differences ( 1 , 40 , 46 , 48 , 49 , 54 ), nine found that Latino patients had significantly higher nonadherence rates ( 6 , 47 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ), and one found that monolingual Spanish-speaking patients, but not bilingual patients, were more likely to be nonadherent than Euro-American patients ( 56 ). In ten of 14 studies, African Americans had significantly greater nonadherence rates than Euro-Americans ( 1 , 6 , 46 , 49 , 51 , 54 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 60 ), whereas four found no difference ( 47 , 48 , 50 , 57 ). Seven of the ten studies that compared rates between Latinos and African Americans found no difference ( 1 , 47 , 49 , 50 , 51 ), and three found that Latinos had lower nonadherence rates ( 54 , 58 , 60 ).

More objective measures of adherence

Eleven studies ( 1 , 6 , 46 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 60 ) used MEMS caps, calculations from pharmacy data (including MPRs, CPRs, and CMGRs), or urine testing. None of the studies that included only Latinos used these methods. Six of the 11 studies reported rates by group ( 1 , 6 , 51 , 56 , 58 , 60 ). In these studies the mean nonadherence rate was 43.7%±18.7% for Latinos, 36.5%±18.9% for Euro-Americans, and 49.5%±17.7% for African Americans.

Outcomes and factors related to Latino nonadherence

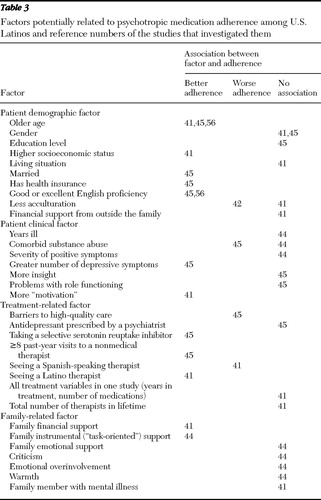

Five of the 21 studies ( 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 56 ) included a majority of Latino participants and examined outcomes of and risk and protective factors for nonadherence specifically for Latinos ( Table 3 ).

|

Only one study ( 56 ) made cross-cultural comparisons of risk factors, investigating the most significant factors for each group. Thus we were unable to answer the question of the relative importance of these identified factors for Latinos compared with other groups, except through comparisons with previously published reviews. Also, there was little overlap between the reports in terms of factors examined. Therefore, direct comparisons of the relative importance of the identified factors were not possible. The one study that made cross-cultural comparisons identified older age among monolingual Spanish-speaking Latinos and more years of previous treatment and fewer depressive symptoms among Euro-Americans as predictors of higher adherence ( 56 ). Nonadherence was found to predict a worse illness course in the two studies that examined the health-related outcomes of nonadherence ( 42 , 43 ).

Language, acculturation, and nonadherence

Only two studies explored the relationship between patients' preferred language and nonadherence, and both found that monolingual Spanish speakers were significantly more likely to be nonadherent ( 45 , 56 ), even after controlling for important cofactors, such as age and number of symptoms. In the two studies that evaluated the interaction between acculturation and nonadherence, one found that acculturation was not related to adherence ( 41 ) and one found that less acculturated patients were significantly less adherent ( 42 ). If language is used as a proxy for acculturation ( 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 ), then three ( 42 , 45 , 56 ) of four studies ( 41 , 42 , 45 , 56 ) found higher nonadherence in less acculturated Latinos. Because socioeconomic status is likely a particularly important potential cofactor in the relationship between nonadherence and language or acculturation, we examined whether each of these studies controlled for socioeconomic status. Of the studies that found that monolingual Spanish speakers were more likely to be nonadherent, one study controlled for socioeconomic status by controlling for education and health insurance status ( 45 ), and in the other study all patients had similar socioeconomic status and access to services ( 56 ). In the studies that examined acculturation, one controlled for socioeconomic status ( 41 ) and found that socioeconomic status, but not acculturation, was significantly associated with nonadherence. The other did not control for socioeconomic status, but a majority of participants were from similarly lower socioeconomic groups ( 42 ).

Providers' language and ethnicity and nonadherence

One study that assessed the effect of providers' language found that Latino patients who saw a Spanish-speaking non-Latino therapist were less likely to adhere to medication treatment; however, the study also found that Latino patients who were treated by a Latino therapist were more likely to adhere ( 41 ). The authors found this surprising and hypothesized that the difference may have resulted from the ubiquitous interpretation and translation services that were available at the study clinic. It may be that ethnic concordance with the provider, not language alone, may lead to better adherence among Latino patients.

Socioeconomic and insurance status and quality of care

Only one study examined the relationship between socioeconomic status and nonadherence ( 41 ). It found that higher socioeconomic status was associated with lower nonadherence. Having health insurance, either public or private, was associated with lower nonadherence in the one study that examined this relationship ( 45 ). That study also reported that barriers to accessing high-quality care led to a greater likelihood of nonadherence.

Other nonadherence risk factors

In the studies that examined age, two found that younger age predicted higher nonadherence for all Latino respondents ( 41 , 45 ), whereas in a third study, this relationship was found only for monolingual Spanish-speaking participants ( 56 ). One study identified problems with drug abuse ( 45 ) as a risk factor for nonadherence; however, another study found that abstinence from street drugs (marijuana was excluded from the definition) was not significantly related to adherence ( 44 ).

Other nonadherence protective factors

Factors associated with better adherence in individual studies included greater family instrumental support (task-oriented or hands-on assistance) ( 44 ), greater financial support from family ( 41 ), more "motivation" (as assessed by patients' keeping appointments, requesting refills when due, and asking for medication changes if they felt that their medications were not working) ( 41 ), being married ( 45 ), having a greater number of depressive symptoms ( 45 ), taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor as opposed to another type of antidepressant ( 45 ), and having made eight or more visits to a nonmedical therapist in the past year ( 45 ).

Other culturally relevant findings

Sleath and colleagues ( 52 , 53 ) reported that in addition to having higher nonadherence rates, Latino patients were significantly less likely than Euro-Americans to receive information about antidepressants from their physicians and to share information about antidepressant use with their physicians and were also less likely to express complaints about their antidepressants. A study of patients with schizophrenia or depression found that Latinos were significantly less likely than Euro-Americans to characterize their life situation in terms of mental illness ( 40 ).

Discussion

We reviewed the literature to examine rates of nonadherence to antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers among Latinos living in the United States, as well as risk factors for and influences of language and acculturation on nonadherence. We found that the mean rate of psychotropic nonadherence among Latinos was 44% in studies that included only Latinos. In studies that included multiple racial and ethnic groups, the rate among Latinos was approximately 40%, which was higher than the mean nonadherence rate of roughly 30% among Euro-Americans and comparable to the rate of roughly 40% among African Americans.

The effect size of the difference between rates for Latinos and Euro-Americans was .64, suggesting a medium to large difference. We purposely compared rates among racial and ethnic groups by using only studies that had rates available for all groups, so the higher nonadherence rates among Latinos and African Americans compared with Euro-Americans are not the result of differences in study design or adherence measure. A majority of studies found that Latinos had significantly higher rates of nonadherence than Euro-Americans. Remarkably, none found that Latinos had lower nonadherence, even in bilingual, culturally tailored settings ( 56 ), suggesting that Latinos experience additional barriers to adherence beyond language and cultural barriers.

Consistent with findings of previous studies, nonadherence predicted a worse illness course in studies that investigated outcomes. Some risk factors for nonadherence that were identified among Latinos are similar to those found in the wider adherence literature; they included substance abuse, barriers to access to high-quality care, lack of health insurance, and limited family support. Two studies identified monolingual Spanish status as a nonadherence risk factor. If poor English proficiency is considered to be a proxy for less acculturation ( 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 ), then three of four studies found that less acculturation was predictive of nonadherence. Protective factors for Latinos included receiving greater family instrumental and financial support, having higher socioeconomic status, being older, being married, being more proactive in one's care, having public or private insurance, and having made eight or more visits to a therapist in the past year.

Previous reviews have noted great variability in psychotropic nonadherence rates (10%–77%), with mean rates of 35%–60% ( 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). The mean rates for Latinos and African Americans found in our review are within that mean range, but the rate for Euro-Americans is slightly lower (30%). In studies that used pharmacy data, MEMS caps, or urine testing as a measure, the nonadherence rates in all groups were higher than in the studies using other measures—44% for Latinos, 49% for African Americans, and 37% for Euro-Americans, which is within the mean range found in previous reviews for Euro-Americans. Studies that rely on patient or provider report tend to underestimate nonadherence rates. All studies reviewed here that included only Latinos used patient, family, or provider report to measure adherence, but surprisingly they found a higher mean nonadherence rate (44%) than studies that used more objective measures (40%). This difference may result from the use of a combination of patient and family reports and chart review to assess adherence in some of the studies ( 43 , 44 ). The higher rates could also result from differences in study design or patient population. Cultural factors might lead to greater reliability of patient and provider reports in Latino populations compared with non-Latino populations.

Family likely has a particularly important role in the care and health outcomes of Latino patients with mental illness compared with other groups ( 24 , 38 , 67 ). Two studies investigated which specific types of family assistance were most predictive of adherence and found that greater financial support from family ( 41 ) and more family instrumental support ("task-oriented" assistance) ( 44 ) predicted better adherence.

Limitations

Our review has several limitations. Although we conducted a comprehensive search, it is possible we missed a relevant study. This is a comprehensive review of summary data, not a meta-analysis. Included studies were heterogeneous with respect to study objectives and design, diagnoses studied, sample size, and proportion of Latino participants. Many of the larger studies were limited by small percentages of Latino patients. In addition, there was extensive variability in the measure of adherence, the period for which adherence was measured (one week to one year), and even the definition of adherence, with some studies using dichotomous measures and others measuring partial adherence in addition to nonadherence and adherence. This heterogeneity, particularly the variability in the time for which adherence was measured, likely led to the wide range in nonadherence rates in the studies reviewed, even among studies that used more objective adherence measures, because adherence is known to decrease over time ( 59 ). Although this variability could affect the reliability of absolute nonadherence rates, it likely did not affect our ability to compare relative rates between racial or ethnic groups because we included only studies in which data on rates were available for all three groups. Therefore, we know that any differences in rates between groups did not result from differences in adherence measure or study design. Also, we separately examined studies that used only adherence measures regarded to be more objective and found somewhat higher nonadherence rates among all groups, but the pattern of relative rates between groups was similar to that in the analysis that included all the studies.

Another limitation of the literature was that none of the reports examined every risk or protective factor identified—in fact, many risk and protective factors were investigated only by one or a few studies—which makes it impossible to draw conclusions about the relative importance of each factor. Only one study conducted cross-cultural comparisons of risk and protective factors. Similarly, we could not compare nonadherence rates or factors most relevant by diagnosis and race-ethnicity because most studies included participants with only one diagnosis. In addition, a number of factors that are likely to significantly influence adherence among Latinos were not investigated, such as cultural attitudes and beliefs about mental illness and treatments, health literacy, stigma ( 68 ), insight, efficacy and tolerability of medications, side effects, use of alternative treatments, and dietary and genetic effects on medication metabolism. Only a few studies examined factors unique to Latinos, such as language and acculturation. Similarly, potentially modifiable mechanisms that influence adherence, such as socioeconomic status, health insurance, and barriers to high-quality care, were examined only in single reports. We were able to compare rates only between Latinos, Euro-Americans, and African Americans because of the literature's general lack of adherence investigations in other groups. The U.S. Latino population is quite heterogeneous both culturally and in important indicators of population health ( 24 , 28 ). Many of these studies were conducted with Mexican Americans and veteran populations, and thus the results are likely not applicable to all Latino communities living in the United States.

It is important to note that the summary mean nonadherence rates were generally unadjusted for potentially important cofactors, such as socioeconomic status. Therefore, these cofactors must be considered possible contributors to the lower nonadherence rates seen among Latinos and African Americans compared with Euro-Americans. Similarly, cofactors such as access to health care or socioeconomic status must be considered as possible explanations for the relationships between risk and protective factors and nonadherence. For example, the relationship between less acculturation and nonadherence noted by three of four studies could be mediated by a variety of factors, including socioeconomic status. This remains an open question. Two of the four studies examining acculturation directly controlled for socioeconomic status—one continued to find an association between nonadherence and less acculturation ( 45 ) and the other found no association ( 41 ). Other ways in which a lower degree of acculturation could lead to nonadherence include impaired patient-physician communication because of language barriers ( 45 ) and difficulty navigating the U.S. health care system.

Despite these limitations, our results clearly suggest that Latinos are at higher risk of psychotropic medication nonadherence than Euro-Americans. Remarkably, this risk was observed across various study designs, diagnostic categories, medication types, clinical settings, and Latino subgroups. The higher rates of nonadherence seen among Latinos were comparable to the rates among African Americans, another disadvantaged racial-ethnic minority group. Although the existing literature limited our ability to answer the question of which risk factors are most relevant for Latinos, we have summarized all the influences on adherence among Latinos that have been investigated to date and have identified factors that are particularly relevant for Latinos.

Research recommendations

As previously recommended ( 17 , 18 , 69 ), a standard definition and measure of adherence would greatly improve interpretation of the broader adherence literature. Because people are less than optimally adherent to medications in different ways and for different reasons, quantifying adherence into more categories than adherent or nonadherent would be helpful in better understanding adherence and developing interventions to improve it. Additional categories have been used in more recent studies ( 6 , 58 , 59 , 60 ), and one found that patients who filled prescriptions more often than expected incurred the highest health care costs of all nonadherent patients ( 6 ).

In terms of recommendations for studying adherence rates specifically among Latinos, we first encourage future studies to include more adequate numbers of Latinos. This is consistent with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) initiative to increase representation of participants from racial-ethnic minority groups in research studies ( 70 ). Because of the great heterogeneity of U.S. Latino populations ( 71 ), we recommend including Latinos from all the diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds that make up the larger U.S. Latino population as well as specifying the degree of acculturation, country of origin or cultural background, socioeconomic situation, and preferred language, which was done in many of the studies included in this review. This heterogeneity also gives added weight to previous recommendations for local, community-based, participatory research ( 38 , 72 ) to develop optimally relevant and lasting interventions to improve adherence. In addition, we recommend cross-cultural comparisons that investigate the relative importance of risk and protective factors for different racial and ethnic groups, including Asian Americans and American Indians, who we noted were rarely included in meaningful numbers in adherence investigations.

Although adherence measures that rely on pharmacy records are typically considered more reliable than other measures, such as patient report, pharmacy records may underestimate adherence among patients in lower socioeconomic groups, who, for example, may rely on free samples from physicians (which would not be displayed in pharmacy records) to bridge gaps in insurance coverage or reduce prescription costs. Pharmacy records also do not include herbal and over-the-counter medications, which could affect adherence. Therefore, future investigators may want to consider supplementing pharmacy or MEMS caps data with other sources of adherence data, such as patient and family report combined with chart review ( 44 ), or conducting detailed structured patient interviews ( 55 ) to provide a comprehensive examination of nonadherence and its causes.

Ultimately, research needs to identify mechanisms whereby suboptimal adherence occurs among Latinos and racial-ethnic minority groups in general. Hypothesis-driven research characterizing the role of moderators and mediators of adherence is needed. Mechanisms thus identified would be the basis for more effective interventions. Our review gives additional support to the recommendation of the NIMH-sponsored expert consensus meeting of Latino mental health services researchers to investigate the effects on adherence of language, acculturation, family support, health insurance, poverty, and access to high-quality care, including therapy ( 38 ). Given the findings that socioeconomic and health insurance status and barriers to high-quality care were related to adherence, these factors should be included as potential cofactors in future analyses of adherence. Particular attention should be paid to including these factors when comparing racial-ethnic groups, because group differences in adherence have been found to disappear when, for example, income is accounted for ( 73 ). As previously noted, preferred language may be a better predictor of health patterns than ethnicity ( 56 , 65 ). It is essential to include adequate numbers of Spanish-speaking as well as bilingual and English-speaking patients and clinicians in future research to better understand these relationships. In addition to further explorations of the influence of factors noted in this review, we hope that future studies will investigate other likely influences on adherence. One such recently identified factor is stigma, which ranked second only to side effects in concerns about antidepressant use identified by Latino focus groups ( 68 ). Another is the role of culture in shaping the experience and interpretation of mental illness.

One study noted that although Latinos with depression were more likely to be nonadherent than Euro-Americans with depression, no difference was found for schizophrenia ( 40 ). This finding deserves focused attention in future investigations. We recommend that researchers examine nonadherence rates by both ethnicity and diagnosis. Also, cross-cultural explorations of which factors are most important for which diagnostic groups and whether mechanisms of nonadherence differ between diagnostic and racial-ethnic groups would be a significant new contribution to the literature.

Clinical recommendations

Because of the limitations of the literature, we cannot offer specific clinical recommendations at this time. However, the data provide some general clinical guidelines. Currently, there are no evidence-based interventions specifically to improve psychotropic medication adherence among Latinos. However, potentially applicable are findings from broader quality improvement interventions ( 74 ), adherence interventions in predominantly non-Latino populations ( 75 , 76 ), adherence interventions for nonpsychiatric diseases that have been tested among Latinos ( 77 , 78 , 79 ), and broader mental health interventions for Latinos ( 80 , 81 ), as well as from clinical experience ( 82 ) and policy recommendations ( 39 ).

Because most patients are likely to have adherence problems at some point ( 59 ), reassessing adherence regularly and repeatedly is important. Incorporating pharmacy records ( 3 ) in addition to patient and family report will increase the likelihood of detecting adherence difficulties. The finding that Latino patients were less likely than Euro-Americans to discuss their medications with their physician ( 52 , 53 ) suggests that physicians should be particularly mindful of encouraging medication discussions with their Latino patients. Physicians' proactive role in these discussions is particularly important because a common practice in many Latino cultures is to show deference toward physicians ( 83 ). Information about medication should be in Spanish and use simple terms enhanced with visual aids, where appropriate, depending on the language preference and educational attainment of the patient population served. Similarly, the prominence of stigma and culturally influenced negative associations in regard to antidepressants that were found in recent focus groups with Latinos who were prescribed antidepressants ( 68 ) indicates that inquiring about and addressing these issues could be useful for improving adherence.

Because of the high prevalence of nonadherence in all populations and because the reasons for nonadherence are likely to differ across patients, we strongly recommend assessing adherence and barriers to and mechanisms of adherence individually for every patient. Although some factors identified in our review, such as young age, cannot be modified, other contributors to nonadherence could be addressed in clinical settings. The findings by two studies in this review—that greater family financial and instrumental support were predictive of better adherence—suggest that involving family members in these specific ways whenever possible might be particularly beneficial for Latino patients. In addition, the higher antidepressant adherence among Latinos who had eight or more visits to a nonmedical therapist ( 45 ) is consistent with findings from predominantly Euro-American samples ( 57 , 84 ) and with a position paper calling for culturally appropriate, practice-initiated quality improvement interventions, including psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic components ( 39 ). The finding that Latinos were more likely than Euro-Americans to want counseling and less likely to want antidepressants ( 85 ) suggests that therapy may be an especially important adherence enhancer for Latinos.

Latinos are least likely of all U.S. racial-ethnic groups to have public or private health insurance; the uninsured rate is 35.7%, compared with 12.6% for Euro-Americans ( 86 ). This disparity lends added significance to the finding that having public or private health insurance predicted better adherence among Latinos ( 45 ). Because lower socioeconomic status was associated with lower adherence ( 41 ), and Latinos are disproportionately represented in lower socioeconomic strata ( 24 , 86 ), clinicians should pay particular attention to ensuring that their patients can afford the psychotropic medications that they prescribe. Because barriers to high-quality care were associated with worse adherence, clinicians can likely improve adherence simply by ensuring that they are providing high-quality care. These findings also suggest that society-level interventions that increase access to health insurance, medications, and high-quality care would improve adherence.

Culturally and linguistically tailored care is likely important for establishing good clinician-patient relationships, which are associated with improved adherence ( 7 , 18 , 19 , 87 , 88 ). Clinicians should attend to cultural contexts that shape how their patients interpret and experience mental illness, because these likely affect adherence. As previously noted by several authors ( 82 , 89 , 90 ) and suggested by the findings of two studies in this review ( 41 , 56 ), even clinics with primarily bilingual, bicultural staff can have cultural divides with their patients because of differences in socioeconomic status and health models and beliefs. Recognizing those divides and working collaboratively with patients can help overcome these barriers and improve adherence ( 82 , 91 ).

Conclusions

U.S. Latinos who receive mental health treatment appear to be at increased risk of psychotropic medication nonadherence compared with Euro-Americans. Our findings suggest that as clinicians and researchers examine ways to improve adherence to psychotropic medications among Latino patients, important considerations include prescribing treatment regimens that patients can afford; overcoming barriers to high-quality care, including language, socioeconomic, and cultural barriers; recognizing family involvement and psychotherapy as potentially important adherence enhancers; and ensuring that interventions to improve adherence are culturally appropriate.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was partly supported by NIMH grant MH-66248 and by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Dr. Jeste is a consultant for Solvay-Wyeth, Janssen, and Bristol-Meyers Squibb. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al: Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:453–460, 2006Google Scholar

2. Weiden PJ, Olfson M: Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21: 419–429, 1995Google Scholar

3. Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al: Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care 40:630–639, 2002Google Scholar

4. Terkelsen KG, Menikoff A: Measuring the costs of schizophrenia. Implications for the post-institutional era in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 8:199–222, 1995Google Scholar

5. Gilbert PL, Harris MJ, McAdams LA, et al: Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients: a review of the literature. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:173–188, 1995Google Scholar

6. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al: Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:692–699, 2004Google Scholar

7. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637–651, 1997Google Scholar

8. Goodwin GM: Prophylaxis of bipolar disorder: how and who should we treat in the long term? European Neuropsychopharmacology 9(suppl 4):S125–S129, 1999Google Scholar

9. Mander AJ, Loudon JB: Rapid recurrence of mania following abrupt discontinuation of lithium. Lancet 2:15–17, 1988Google Scholar

10. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al: Factors associated with pharmacologic noncompliance in patients with mania. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:292–297, 1996Google Scholar

11. Tondo L, Jamison KR, Baldessarini RJ: Effect of lithium maintenance on suicidal behavior in major mood disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 836:339–351, 1997Google Scholar

12. Johnson RE, McFarland BH: Lithium use and discontinuation in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:993–1000, 1996Google Scholar

13. Burton WN, Chen CY, Conti DJ, et al: The association of antidepressant medication adherence with employee disability absences. American Journal of Managed Care 13:105–112, 2007Google Scholar

14. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al: Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet 361:653–661, 2003Google Scholar

15. Gopinath S, Katon WJ, Russo JE, et al: Clinical factors associated with relapse in primary care patients with chronic or recurrent depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 101:57–63, 2007Google Scholar

16. Katon W, Cantrell CR, Sokol MC, et al: Impact of antidepressant drug adherence on comorbid medication use and resource utilization. Archives of Internal Medicine 165:2497–2503, 2005Google Scholar

17. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196–201, 1998Google Scholar

18. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al: Prevalence of and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:892–909, 2002Google Scholar

19. Lingam R, Scott J: Treatment non-adherence in affective disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 105:164–172, 2002Google Scholar

20. Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Kaczynski R, et al: Medication non-adherence in bipolar disorder: a patient-centered review of research findings. Clinical Approaches in Bipolar Disorders 3:56–64, 2004Google Scholar

21. Becker MA, Young MS, Ochshorn E, et al: The relationship of antipsychotic medication class and adherence with treatment outcomes and costs for Florida Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 34:307–314, 2007Google Scholar

22. Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland LA, et al: Poor antipsychotic adherence among patients with schizophrenia: medication and patient factors. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:255–264, 2004Google Scholar

23. Sajatovic M, Elhaj O, Youngstrom EA, et al: Treatment adherence in individuals with rapid cycling bipolar disorder: results from a clinical-trial setting. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 27:412–414, 2007Google Scholar

24. Ramirez RR, de la Cruz PG: The Hispanic Population in the United States, March 2002. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, June 2003. Available at www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/p20-545.pdf Google Scholar

25. Rumbaut RG: Ages, life stages, and generational cohorts: decomposing the immigrants' first and second generations in the United States. International Migration Review 38:1160–1205, 2004Google Scholar

26. Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, et al: Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health 96:1342–1346, 2006Google Scholar

27. Wells KB, Golding JM, Hough RL, et al: Acculturation and the probability of use of health services by Mexican Americans. Health Services Research 24:237–257, 1989Google Scholar

28. Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, et al: Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annual Review of Public Health 26:367–397, 2005Google Scholar

29. Balls Organista P, Organista KC, Kurasaki K: Relationship between acculturation and ethnic minority mental health, in Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research, vol 1. Edited by Chun KM, Organista PB, Marin G. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2003Google Scholar

30. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al: Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:928–934, 1999Google Scholar

31. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, et al: Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:1226–1233, 2004Google Scholar

32. Virnig B, Huang Z, Lurie N, et al: Does Medicare managed care provide equal treatment for mental illness across races? Archives of General Psychiatry 61:201–205, 2004Google Scholar

33. Vitiello B, Burnam MA, Bing EG, et al: Use of psychotropic medications among HIV-infected patients in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:547–554, 2003Google Scholar

34. Ruiz P, Varner RV, Small DR, et al: Ethnic differences in the neuroleptic treatment of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Quarterly 70: 163–172, 1999Google Scholar

35. Wagner GJ, Maguen S, Rabkin JG: Ethnic differences in response to fluoxetine in a controlled trial with depressed HIV-positive patients. Psychiatric Services 49:239–240, 1998Google Scholar

36. Sanchez-Lacay JA, Lewis-Fernandez R, Goetz D, et al: Open trial of nefazodone among Hispanics with major depression: efficacy, tolerability, and adherence issues. Depression and Anxiety 13:118–124, 2001Google Scholar

37. Marcos LR, Cancro R: Pharmacotherapy of Hispanic depressed patients: clinical observations. American Journal of Psychotherapy 36:505–512, 1982Google Scholar

38. Vega WA, Karno M, Alegria M, et al: Research issues for improving treatment of US Hispanics with persistent mental disorders. Psychiatric Services 58:385–394, 2007Google Scholar

39. Lewis-Fernandez R, Das AK, Alfonso C, et al: Depression in US Hispanics: diagnostic and management considerations in family practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 18:282–296, 2005Google Scholar

40. Jenkins JH: Subjective experience of persistent schizophrenia and depression among US Latinos and Euro-Americans. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:20–25, 1997Google Scholar

41. Hosch HM, Barrientos GA, Fierro C, et al: Predicting adherence to medications by Hispanics with schizophrenia. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 17:320–333, 1995Google Scholar

42. Telles C, Karno M, Mintz J, et al: Immigrant families coping with schizophrenia: behavioral family intervention v case management with a low-income Spanish-speaking population. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:473–479, 1995Google Scholar

43. Karno M, Jenkins JH, de la SA, et al: Expressed emotion and schizophrenic outcome among Mexican-American families. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 175:143–151, 1987Google Scholar

44. Ramirez Garcia JI, Chang CL, Young JS, et al: Family support predicts psychiatric medication usage among Mexican American individuals with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:624–631, 2006Google Scholar

45. Hodgkin D, Volpe-Vartanian J, Alegria M: Discontinuation of antidepressant medication among Latinos in the USA. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 34:329–342, 2007Google Scholar

46. Rosenheck R, Chang S, Choe Y, et al: Medication continuation and compliance: a comparison of patients treated with clozapine and haloperidol. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:382–386, 2000Google Scholar

47. Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM, et al: Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: influence of patient-physician communication. JAMA 288:1403–1409, 2002Google Scholar

48. Li J, McCombs JS, Stimmel GL: Cost of treating bipolar disorder in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program. Journal of Affective Disorders 71:131–139, 2002Google Scholar

49. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al: Predictors of medication discontinuation by patients with first-episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophrenia Research 57:209–219, 2002Google Scholar

50. Barrio C, Yamada AM, Atuel H, et al: A tri-ethnic examination of symptom expression on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research 60:259–269, 2003Google Scholar

51. Opolka JL, Rascati KL, Brown CM, et al: Role of ethnicity in predicting antipsychotic medication adherence. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 37:625–630, 2003Google Scholar

52. Sleath B, Rubin RH, Huston SA: Hispanic ethnicity, physician-patient communication, and antidepressant adherence. Comprehensive Psychiatry 44:198–204, 2003Google Scholar

53. Sleath B, Rubin RH, Wurst K: The influence of Hispanic ethnicity on patients' expression of complaints about and problems with adherence to antidepressant therapy. Clinical Therapeutics 25:1739–1749, 2003Google Scholar

54. Farabee D, Shen H, Sanchez S: Program-level predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence among parolees. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 48:561–571, 2004Google Scholar

55. Ayalon L, Arean PA, Alvidrez J: Adherence to antidepressant medications in black and Latino elderly patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:572–580, 2005Google Scholar

56. Diaz E, Woods SW, Rosenheck RA: Effects of ethnicity on psychotropic medications adherence. Community Mental Health Journal 41:521–537, 2005Google Scholar

57. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, et al: Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:101–108, 2006Google Scholar

58. Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow FC, et al: Treatment adherence with antipsychotic medications in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 8:232–241, 2006Google Scholar

59. Valenstein M, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, et al: Antipsychotic adherence over time among patients receiving treatment for schizophrenia: a retrospective review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:1542–1550, 2006Google Scholar

60. Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow F, et al: Treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 58:855–863, 2007Google Scholar

61. Velligan DI, Wang M, Diamond P, et al: Relationships among subjective and objective measures of adherence to oral antipsychotic medications. Psychiatric Services 58:1187–1192, 2007Google Scholar

62. Grymonpre RE, Didur CD, Montgomery PR, et al: Pill count, self-report, and pharmacy claims data to measure medication adherence in the elderly. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 32:749–754, 1998Google Scholar

63. Jeste ND, Moore DJ, Goldman SR, et al: Predictors of everyday functioning among older Mexican Americans vs Anglo-Americans with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:1304–1311, 2005Google Scholar

64. Franzini L, Fernandez-Esquer ME: Socioeconomic, cultural, and personal influences on health outcomes in low income Mexican-origin individuals in Texas. Social Science and Medicine 59:1629–1646, 2004Google Scholar

65. Folsom DP, Gilmer T, Barrio C, et al: A longitudinal study of the use of mental health services by persons with serious mental illness: do Spanish-speaking Latinos differ from English-speaking Latinos and Caucasians? American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1173–1180, 2007Google Scholar

66. Vega WA, Sribney WM, Achara-Abrahams I: Co-occurring alcohol, drug, and other psychiatric disorders among Mexican-origin people in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 93:1057–1064, 2003Google Scholar

67. Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P: Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Mental Health Journal 32:243–260, 1996Google Scholar

68. Interian A, Martinez IE, Guarnaccia PJ, et al: A qualitative analysis of the perception of stigma among Latinos receiving antidepressants. Psychiatric Services 58:1591–1594, 2007Google Scholar

69. Velligan DI, Lam YW, Glahn DC, et al: Defining and assessing adherence to oral antipsychotics: a review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:724–742, 2006Google Scholar

70. NIMH Five-Year Strategic Plan for Reducing Health Disparities. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, Nov 16, 2001. Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports Google Scholar

71. Alegria M, Canino G, Shrout PE, et al: Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant US Latino groups. American Journal of Psychiatry 165:359–369, 2008Google Scholar

72. Wells K, Miranda J, Bruce ML, et al: Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:955–963, 2004Google Scholar

73. Gellad WF, Haas JS, Safran DG: Race/ethnicity and nonadherence to prescription medications among seniors: results of a national study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22:1572–1578, 2007Google Scholar

74. Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research 38:613–630, 2003Google Scholar

75. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al: Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1653–1664, 2002Google Scholar

76. Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Leckband S, et al: Interventions to improve antipsychotic medication adherence: review of recent literature. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 23:389–399, 2003Google Scholar

77. Betancourt JR, Carrillo JE, Green AR: Hypertension in multicultural and minority populations: linking communication to compliance. Current Hypertension Reports 1:482–488, 1999Google Scholar

78. Van Servellen G, Carpio F, Lopez M, et al: Program to enhance health literacy and treatment adherence in low-income HIV-infected Latino men and women. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 17:581–594, 2003Google Scholar

79. Bonner S, Zimmerman BJ, Evans D, et al: An individualized intervention to improve asthma management among urban Latino and African-American families. Journal of Asthma 39:167–179, 2002Google Scholar

80. Kopelowicz A, Zarate R, Gonzalez SV, et al: Disease management in Latinos with schizophrenia: a family-assisted, skills training approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:211–227, 2003Google Scholar

81. Patterson TL, Bucardo J, McKibbin CL, et al: Development and pilot testing of a new psychosocial intervention for older Latinos with chronic psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31:922–930, 2005Google Scholar

82. Opler LA, Ramirez PM, Dominguez LM, et al: Rethinking medication prescribing practices in an inner-city Hispanic mental health clinic. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 10:134–140, 2004Google Scholar

83. Erzinger S: Communication between Spanish-speaking patients and their doctors in medical encounters. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 15:91–110, 1991Google Scholar

84. Jamison KR, Gerner RH, Goodwin FK: Patient and physician attitudes toward lithium: relationship to compliance. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:866–869, 1979Google Scholar

85. Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al: The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care 41:479–489, 2003Google Scholar

86. The Uninsured: A Primer. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Family Foundation, Oct 2008. Available at www.kff.org/uninsured/7451.cfm Google Scholar

87. Cochran SD, Gitlin MJ: Attitudinal correlates of lithium compliance in bipolar affective disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 176:457–464, 1988Google Scholar

88. Van Servellen G, Lombardi E: Supportive relationships and medication adherence in HIV-infected, low-income Latinos. Western Journal of Nursing Research 27:1023–1039, 2005Google Scholar

89. Ruiz P, Ruiz PP: Treatment compliance among Hispanics. Journal of Operational Psychiatry 14:112–114, 1983Google Scholar

90. Lorion RP: Patient and therapist variables in the treatment of low-income patients. Psychological Bulletin 81:344–354, 1974Google Scholar

91. Sajatovic M, Davies M, Bauer MS, et al: Attitudes regarding the collaborative practice model and treatment adherence among individuals with bipolar disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry 46:272–277, 2005Google Scholar