The Role of Patient Activation in Psychiatric Visits

Living successfully with chronic health conditions requires active collaboration in managing illness—that is, the consumer and health care provider working together to help the consumer identify problem areas, set goals, learn self-management skills, and participate in actions and behaviors that will improve chances of recovery ( 1 ). An active partnership is critical because the majority of time spent managing chronic illnesses takes place when the consumer is on his or her own in the community rather than in the provider's office. Further, reviews have shown that positive, relationship-centered approaches translate into higher levels of trust and satisfaction, reduced emotional burden, and improved biomedical markers, such as blood pressure and blood sugar control ( 2 ). Relationships in which active patients take a greater control in treatment appear to be particularly important predictors of patients' physical health ( 3 ).

National policy supports an active role for consumers of mental health services, and research indicates that people with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia want to take a role in making decisions about their care ( 4 ). Shared decision making is gaining more attention ( 5 ), and interventions are being developed to improve activation and shared decision making in this population ( 6 ). Unfortunately, tools to assess active participation in managing mental illnesses are lacking ( 5 ).

In the general medical field, the Patient Activation Measure ( 7 ) has been successfully used in a variety of chronic health conditions, including diabetes, arthritis, and high blood pressure. The scale assesses an individual's knowledge of and skill and confidence in actively managing illness, and patient activation has been associated with a variety of self-management behaviors, including diet, exercise, nutrition, self-monitoring, and reading about medications. Patient activation has also been associated with service utilization, medication adherence, satisfaction with services, and quality of life ( 8 ).

To better understand patient activation among people with severe mental illness, we conducted a cross-sectional, mixed-methods, descriptive study assessing consumer-reported and observed patient activation. We hypothesized that consumer-reported activation would be positively related to illness self-management, positive attitudes toward medications, and provider-rated medication adherence. We explored ways consumers were active participants in treatment during visits by identifying themes of activation and rating each consumer's overall activation levels. We hypothesized that observations of activation would be related to consumer-reported activation—that is, people who endorsed high levels of activation on a questionnaire would be rated as having high levels of observed patient activation during the visit.

Methods

The study took place between March 2008 and July 2008 at a community mental health center in a medium-size Midwestern city serving children and adults with severe mental illnesses and a family income of 200% of poverty level or below. The agency organizes treatment teams around the assertive community treatment (ACT) model serving consumers who have a history of hospitalization, homelessness, or incarceration. We contacted prescribers who served adults, and the first four we approached (of five possible) agreed to participate in the study (three psychiatrists and one nurse practitioner). A research assistant scheduled days to recruit ten consumers per provider. During recruitment, agency staff introduced the assistant who described the study and reviewed the informed consent statement. Consumers who participated completed a brief packet of surveys before (or just after) the visit and were paid $10. Providers allowed us to audiotape the visit and provided diagnosis and ratings of substance use disorder and medication adherence; they were not paid for their participation. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

We approached 43 consumers in order to reach our targeted sample of 40 (a 93% participation rate). Two declined citing lack of time, and one declined for personal reasons. Consumers who participated had a mean±SD age of 43.5±15.2 years. Thirty-one consumers (78%) were Caucasian, six (15%) were African American, and three (8%) were from another racial or ethnic group. Most had at least a high school degree (N=28, 70%), and about half were female (N=21, 53%). Diagnoses included schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (N=25, 63%), bipolar disorder (N=4, 10%), major depression (N=8, 20%), or other (N=3, 8%). Six (15%) had a co-occurring substance use disorder. Most were being served by state-certified ACT teams (N=29, 73%).

Activation was assessed with the short-form, mental health version of the Patient Activation Measure ( 7 ). The 13 items refer specifically to "mental health," rather than "health" (for example, "I know what each of my prescribed mental health medications do"). Scores have a theoretical range of 0, lowest levels of activation, to 100, highest levels of activation. Internal consistency was good (Cronbach's alpha=.83); scores ranged from 40.1 to 91.6, with a mean of 57.7±12.5. [A figure showing the distribution of participants' scores on this measure is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Illness self-management was assessed with the client version of the Illness Management and Recovery Scale ( 9 ). The scale consists of 15 items rated on a 5-point behaviorally anchored scale and includes progress toward goals, knowledge about mental illness, involvement with significant others and self-help, time in structured roles, impairment in functioning, symptom distress and coping, relapse prevention and hospitalizations, use of medications, and alcohol and drug use. The scale has demonstrated adequate internal reliability, good test-retest reliability, and convergent validity ( 9 ).

Medication attitudes were assessed with the ten-item Medication Adherence Rating Scale, which has been shown to have adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and positive correlations with related measures ( 10 ). This measure includes items such as "I take my medication only when I am sick" and "My thoughts are clearer on medication."

Provider ratings were given for medication adherence (1, rarely or never; 2, half the time; 3, usually; 4, always or almost always). Providers were asked the diagnosis for each consumer and whether the individual had a co-occurring substance use disorder.

Observations of activation came from the 40 visits (one per consumer) that were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, reviewed for accuracy, deidentified, and imported into Atlas-ti. Through an iterative, consensus-building process, we listened to and reviewed transcripts to identify emergent themes related to activation. Initially four of us reviewed a transcript independently to identify points at which the consumer was active in treatment (or not active when expected) and what led to this identification. We met as a group to discuss our findings and repeated this process on several transcripts until we had a set of defined codes. Then three of us coded transcripts independently. Every third transcript was coded by all three of us, and we met weekly to compare coding, resolve discrepancies, and refine coding through consensus to help maintain interrater reliability. We also rated each transcript on the extent to which the consumer was active in the negotiation about treatment, seemed interested in the management of his or her mental illness, and was involved in controlling symptoms of his or her mental illness; all these ratings were based on research of rating scales in diabetes management ( 11 ). However, we used a cruder rating scale than the diabetes study (0, not at all; 1, a little; 2, somewhat; 3, a lot) because we did not have the prior data for more fine-grained levels of activation.

We examined Pearson correlations among all measures, and categorical variables (for example, substance use disorder) were dummy-coded as 0 or 1 to indicate presence or absence of the variable. We used correlations to test the hypotheses that consumer-reported activation would be related to illness self-management and medication adherence, and to examine whether consumers' ratings and providers' ratings would predict coder ratings of levels of activation. Thematic analysis identified ways in which consumers were active in treatment.

Results

Background characteristics (age, gender, race, education, and presence or absence of a diagnosis of schizophrenia) were unrelated to consumer-reported activation, illness self-management, medication attitudes, or medication adherence. As shown in Table 1 , consumer-reported activation was related to higher levels of self-management of illness (r=.46, p<.01) and less substance use disorder according to provider report (r=-.35, p<.05). However, consumer-rated activation was not significantly related to medication attitudes or provider ratings of medication adherence.

|

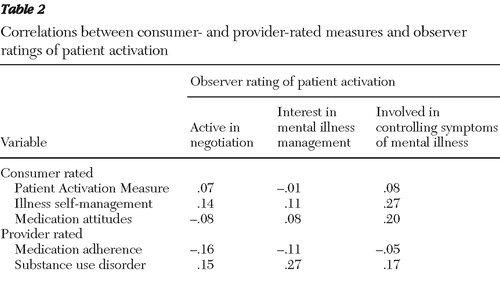

The mean length of a visit was 19.0±6.0 minutes (ranging from 9.0 to 32.2 minutes). Length of visit was not significantly related to consumer-rated activation, illness self-management, medication attitudes, prescriber ratings, or coder ratings of activation. Coder ratings of active involvement that were based on the transcripts were not significantly related to consumer-reported activation, illness self-management, medication attitudes, or medication adherence ( Table 2 ).

|

Thematic analyses revealed four broad types of consumer activation: partnership building, seeking and displaying competence, directing treatment, and missed opportunities. The theme of partnership building included providing opportunities for the provider to praise the consumer, activity outside the visit, and self-disclosure. Opportunities for praise occurred when consumers called attention to positive affect or efforts, often placing themselves in a positive light along the path to recovery. For example, one consumer said, "And my math is getting better … I'm working on it every day." Activity outside the session involved consumer reports of improving mental health (for example, adhering to a medication regimen) or broader life improvement (for example, one consumer said, "I'm going back through the job training program. I have a meeting on that today"). Self-disclosure involved revealing new information containing a moral or affective component, at times prompted by the provider (for example, asking whether a consumer was taking illicit drugs) and at other times unsolicited as could be seen when one consumer said, "I have a lot of anger toward people, a lot…. To be honest with you, it is very, very embarrassing."

The second theme, seeking and displaying competence, was evident when consumers asked questions, often related to medication dosage, side effects, and new or unusual symptoms. Consumers frequently displayed understanding of illness (for example, when symptoms are better or worse) and treatment (for example, knowing timing and dosage of medication), or deeper understanding (for example, recognizing consequences of behaviors such as substance abuse, exercise, and taking medication as prescribed). Another degree of competence emerged when consumers took responsibility for their behaviors: as one consumer said, "I'm a responsible adult … I can't be acting like a teenager."

Directing treatment, the third theme, varied from more passive strategies, such as voicing a concern, to expressing opinions about treatment, to specific requests of the provider. Consumers expressed concern about various issues, including mental health symptoms, medication side effects, physical symptoms, and general life concerns (for example, job stresses, worries about obtaining a high school diploma, and saving for retirement). Consumers offered evaluations of whether the treatment was working and sometimes discussed how they felt about the treatment—for example, a consumer said, "I still don't like the way it [the medication] makes me so tired at night. Cause after I take 'em [the pills] I can't go out … I slur my speech." At the most active end of the spectrum were direct requests. A few consumers asked for a particular medication, for a change in dosage or timing, or specifically that no changes be made. For one consumer, medication was interfering with her work. This consumer said, "I think … is there any way you could start me out right now on a lower dose to get me adjusted, because it pretty much leaves me comatose, really."

Missed opportunities, the final theme, referred to missed opportunities on the consumer's part to become more involved in treatment. Usually this occurred when the consumer responded minimally to provider questions, only to bring up concerns later. In one case the provider was trying to engage the consumer in a conversation about goals, but the consumer responded, "Uh … my goals … I don't remember." (To be fair, this provider had also forgotten, which became clear when the provider remarked, "Well, I can't remember exactly what they were, but I bet you're a lot closer to them now than what you were a year ago.")

Discussion

This is the first study that we are aware of that explored the role of patient activation among people with severe mental illnesses. The version of the Patient Activation Measure that we used had good internal consistency and was correlated with measures of illness self-management and substance use disorder in meaningful ways. Consumers who reported high levels of activation rated themselves as having high levels of illness self-management and recovery and were less likely to be identified by the provider as having a substance abuse problem. Consumer-rated activation was not significantly related to medication attitudes or adherence. However, correlations were in the expected direction, and the small sample restricted our ability to detect anything other than moderate to large effects. Further validation is needed, but this initial examination appears promising for use with people with severe mental illnesses.

Consumer-rated patient activation was not related to coder ratings in terms of negotiation, interest in managing the illness, and involvement in controlling the illness. Even considering the small sample, the magnitude of the relationships was very small. The lack of relationship may reflect a general lack of concordance between attitudes and behaviors; what people think and how they actually behave are different things. Other studies of health care communication have found that patient ratings of involvement have not been correlated with actual behaviors ( 12 ). Similarly, doctors often overestimate their own behaviors, such as the amount of time spent in giving information during encounters ( 13 ). Additionally, we may have observed visits in which highly activated consumers simply did not have issues to bring up at that particular visit and, therefore, did not appear to have high levels of activation. Of course, it is also possible that our coding scheme was not sensitive or was tapping into the wrong areas.

Thematic analysis of the transcripts revealed numerous behaviors reflecting consumer activation. Some of these behaviors were expected, such as asking questions or displaying knowledge, common indicators of patient activation in other chronic illnesses ( 14 ). Basic knowledge about the medical condition and its treatment is fundamental to being an active participant. By contrast, direct requests of providers, perhaps the most active form of behavior, were evident in only a few transcripts. Consumers were generally more indirect or passive, offering opinions and more frequently statements of concern. In the absence of specific coaching for consumers, providers may need to be primed to look for ways in which consumers ask for help. Also, because in-session behavior may not accurately indicate consumer preferences for involvement, providers may need to have more focused discussions about preferences and decision making.

Another interesting set of behaviors involved partnership building, in which consumers talked about how they were actively involved in managing their disorder outside the session, provided opportunities for the provider to praise them, and disclosed personal or sensitive information. This latter behavior, in particular, may indicate the consumer's trust in his or her provider, which in turn may help facilitate the two parties' working together to make decisions that are most beneficial to the consumer. These attributes are fundamental to the concept of relationship-centered care and the role of reciprocal influence in the provider-consumer relationship ( 15 ).

This study was based on a small nonrepresentative sample from one agency and may not be generalizable to the population of individuals with severe mental illnesses. Additionally, because this study was cross-sectional, with one visit per consumer observed, it provides only a window into the consumer's overall experience. We were not able to assess the development of relationships over time nor did we gather information on how long the two parties had been working together or other aspects of the consumer-provider relationship that may influence communication. Despite these limitations, this study provides a more complete picture of patient activation by measuring this construct quantitatively while simultaneously looking for manifestations of activation in actual consumer-provider interactions. Furthermore, although health care communication research tends to focus on the provider role in interactions, this study offers a view of the interaction and activation from the consumer's perspective. Future analyses will focus on the interactions of both the consumer and provider, essential in fully understanding shared decision-making processes. Future research should also examine the relationship between activation and meaningful clinical outcomes, for example, reduced relapses or improved work or other functional indicators. Finally, it would also be interesting to examine the relationship between patient activation and the much broader concept of consumer empowerment, the former being a potentially important component of the latter.

Conclusions

Patient activation is an important construct in collaborative care for chronic illnesses. Although further validation is needed, the Patient Activation Measure appears promising for use with consumers with severe mental illnesses. In addition, activation may take different forms, with consumers displaying a range of behaviors that are related to being an informed, active collaborator in the recovery process.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by an IP-RISP grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R24 MH074670; Recovery Oriented Assertive Community Treatment). The authors appreciate the involvement of prescribers and consumers of Adult and Child Mental Health Center, Inc., and the assistance of Laura Stull, M.S., in data collection.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, et al: Collaborative management of chronic illness. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:1097–1102, 1997Google Scholar

2. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al: The impact of patient-centered care on patient outcomes. Journal of Family Practice 49:796–804, 2000Google Scholar

3. Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J: Patient-centredness in chronic illness: what is it and does it matter? Patient Education and Counseling 51:197–206, 2003Google Scholar

4. Hamann J, Cohen R, Leucht S, et al: Do patients with schizophrenia wish to be involved in decisions about their medical treatment? American Journal of Psychiatry 162:2382–2384, 2005Google Scholar

5. Adams JR, Drake RE: Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Community Mental Health Journal 42:87–105, 2006Google Scholar

6. Deegan PE: The lived experience of using psychiatric medication in the recovery process and a shared decision-making program to support it. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:62–69, 2007Google Scholar

7. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, et al: Development and testing of a short form of the Patient Activation Measure. Health Services Research 40:1918–1930, 2005Google Scholar

8. Mosen DM, Schmittdiel J, Hibbard J, et al: Is patient activation associated with outcomes of care for adults with chronic conditions? Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 30:21–29, 2007Google Scholar

9. Salyers MP, Godfrey JL, Mueser KT, et al: Measuring illness management outcomes: a psychometric study of clinician and consumer rating scales for illness self management and recovery. Community Mental Health Journal 43:459–480, 2007Google Scholar

10. Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA: Reliability and validity of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophrenia Research 42:241–247, 2000Google Scholar

11. Williams GC, McGregor H, Zeldman A, et al: Promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management: evaluating a patient activation intervention. Patient Education and Counseling 56:28–34, 2005Google Scholar

12. Hudak PL, Armstrong K, Braddock C 3rd, et al: Older patients' unexpressed concerns about orthopaedic surgery. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery: American Volume 90:1427–1435, 2008Google Scholar

13. Waitzkin H, Stoeckle JD: The communication of information about illness: clinical, sociological, and methodological considerations. Advances in Psychosomatic Medicine 8:180–215, 1972Google Scholar

14. Street RL Jr, Millay B: Analyzing patient participation in medical encounters. Health Communication 13:61–73, 2001Google Scholar

15. Beach MC, Inui T: Relationship-centered care: a constructive reframing. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(suppl 1):S3–S8, 2006Google Scholar