Key Factors for Implementing Supported Employment

Despite the overwhelming evidence that supported employment is the most effective approach for securing employment for people with psychiatric disabilities ( 1 , 2 ), implementation of this practice and other evidence-based practices remains the exception ( 3 , 4 ). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcome Research Teams found that only 23% of consumers in outpatient programs received any vocational services ( 5 ). Another large survey found that none of the consumers studied had received vocational rehabilitation services in the past 30 days ( 6 ).

The National Evidence-Based Practices Project explored whether evidence-based practices could be implemented in routine mental health settings. Fifty-three agencies across eight states participated in the project by implementing one or more of the following: supported employment, illness management and recovery, integrated treatment for dual disorders, assertive community treatment, and family psychoeducation. Facilitators, barriers, and successful strategies for implementation were examined qualitatively and quantitatively ( 7 ). This article reports on the factors derived from the qualitative analysis that had the most effect on implementing evidence-based supported employment.

Methods

We studied implementation of supported employment in nine sites located in three states. Data were collected at each site for a two-year period (2002–2004) by independent implementation monitors. The intervention, standardized data collection methods, and analysis of site-specific data have been described in several recent publications ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). Institutional review board approval was received within each state and for the project as a whole.

The intervention consisted of access to a toolkit (a workbook, information sheets, videos, and resource lists) and training and ongoing technical support provided by a consultant-trainer. Implementation monitors conducted structured monthly observations of supported employment services and observed trainings, consultation meetings, and all supported employment-related events.

The data collected for this report included supported employment fidelity assessments conducted at baseline and four subsequent six-month intervals as well as qualitative data, as described below. Consultant-trainers and implementation monitors were trained by staff from the National Evidence-Based Practices Project to complete the Supported Employment Fidelity Scale ( 11 ), which includes 15 program-specific items that assess whether the program is provided as the evidence-based practice prescribes. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1, not implemented, to 5, fully implemented. Two-day site visits were conducted to administer the scale. A fidelity score of 66 or higher is defined as high fidelity, a score between 56 and 65 is defined as moderate fidelity, and a score less than 56 is defined as low fidelity ( 11 , 12 ). Consultant-trainers summarized results and recommendations in a fidelity report that was shared with agencies for the purpose of continuous quality improvement.

After each fidelity assessment, implementation monitors conducted semistructured interviews with the program leaders (supervisors of the employment specialists). Consultant-trainers and implementation monitors also documented their own observations of the implementation process. Specifically, these three stakeholder groups provided their perspective regarding the strategies and barriers of implementing supported employment over the six-month period. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed.

The principal unit of analysis for this study was the mental health agency. Field diary entries of site visit observations, interview transcripts, and fidelity assessment reports were entered into Atlas.ti, a qualitative software program ( 13 ).

Data were coded by using an a priori code list developed by staff from the National Evidence-Based Practices Project; the list included 26 dimension codes ( Table 1 ). Information about the development of the code list, training, and reliability testing has been previously published ( 8 ).

|

Once all data were collected, implementation monitors summarized and condensed data into single-site reports (approximately 50 pages), following a protocol developed by staff from the National Evidence-Based Practices Project. Site reports included a number of analytic tools, including a matrix that summarized strategies and barriers for each dimension on the code list. These tools helped implementation monitors examine the raw data both out of context and in context. On the basis of the qualitative data, implementation monitors rated each dimension in the matrix on a 5-point scale for its impact on the implementation effort (2, strongly positive; 1, positive; 0, neither positive nor negative; -1, negative; -2, strongly negative). This method of within-case analysis has been found to be an effective first step for generating insights in large-scale qualitative research studies ( 14 , 15 ). It allows unique patterns in each site to emerge before cross-site comparison is conducted ( 16 ).

For each site report, the factors that strongly influenced the implementation process were extracted from the dimensional matrix. This allowed major themes to be examined out of context. Next, the executive summary and other key narrative sections of each site report were reviewed to recontextualize the data and develop a comprehensive list of key influential factors across the nine sites. The list was then condensed by selecting factors that influenced the implementation in a majority (six or more) of the sites. Each site report was then reviewed individually to examine how the key factor uniquely influenced the implementation process at the specific site. This process of decontextualizing and recontextualizing the data resulted in the emergence of three key factors.

Results

The geographic locations of the sites were diverse; three were located in urban areas (<150,000 persons), four were located in small cities (60,000–100,000 persons), and two were located in rural locations (12,000–14,000 persons). Differences in fidelity scores were not associated with geographic location. Eight of the nine sites were comprehensive mental health agencies, and one provided comprehensive psychosocial services but no clinical services.

Fidelity outcomes

At baseline, none of the sites were following the supported employment model, as reflected by their fidelity scores (mean score=42.6). Five sites had low fidelity scores, and four sites scored in the moderate fidelity range ( Table 2 ). We classified individual items as being areas of deficiency if the fidelity score was 3 or less. At baseline, the nine sites averaged 8.9 areas of deficiency (out of 15 items), ranging from four to 15 areas. Of the four sites with moderate fidelity, three had a vocational team in place that functioned as a unit and provided some vocational services, such as ongoing assessment and rapid job search. However, at baseline, these sites did not provide all vocational services, offer services to all clients, offer integrated services, or conduct individualized job searches. Furthermore, services were mostly provided in the office instead of in the community. Other departures from the model included using enclave-based programs, job coaching subcontracted to a separate agency, agency-based employment, prevocational training, and limited job development.

|

Over the course of the project, all nine sites showed improvement. Improvement over the two-year period is shown in Table 2 . Paired t tests showed significant mean improvement in fidelity from baseline at each of the four follow-up fidelity assessments. By the two-year follow-up, the mean improvement was 24.1 scale points (t=4.61, df=8, p=.002). Eight sites were rated as being at high fidelity, and one site was rated as being at low fidelity.

Qualitative findings

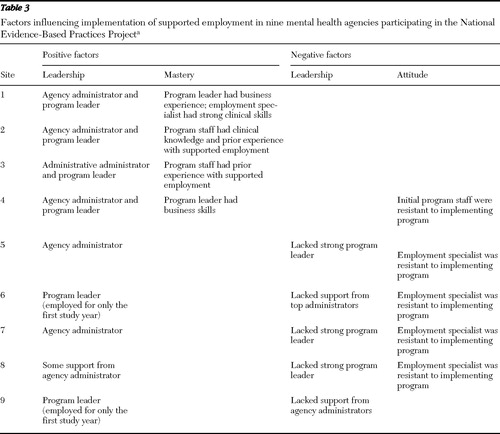

Three factors, leadership, mastery, and attitudes, strongly influenced the implementation (both positively and negatively). Sites with higher fidelity were judged to have fewer insurmountable challenges and to employ more strategies than sites with lower fidelity scores ( Table 3 ).

|

Leadership: multilevel commitment

All nine sites benefited from at least one active leader. Four sites enjoyed strong leadership from both the program leader and agency administrators. Three sites benefited from strong leadership by an agency administrator but lacked program leadership. Two sites had a strong program leader but lacked support from agency administrators.

The executive director or other top-level administrators showed their commitment to implementing supported employment by creating leadership teams to monitor progress, make administrative adjustments, and provide moral support. They also attended planning meetings, participated in supported employment training, and built relationships with community partners, such as off-site mental health clinics, vocational rehabilitation agencies, and local chambers of commerce. Executive directors or administrators also built support by highlighting the initiative to implement supported employment during speaking engagements, including managers meetings, all-staff meetings, board meetings, internal and external consumer forums, and community presentations. They provided the necessary authority to transfer or discharge employment specialists or program leaders who refused to meet their responsibilities for implementing the evidence-based practice, and they created or protected positions in the supported employment program in the face of budget pressures. This type of strong leadership was found to facilitate the implementation process.

For example, as one person surveyed commented, "The director was instrumental in the success of the supported employment program. She is the program leader's supervisor and meets with him regularly to discuss the implementation and sustaining of the evidence-based practice. The director has been a strong advocate from the beginning. She attends all leadership meetings and has followed most, if not all, of the recommendations the consultant-trainer has made."

Successful program leaders tended to focus on structural changes. For example, program leaders in at least two of the sites updated or created vocational policies and procedures that reflected supported employment principles. They assigned employment specialists to treatment teams to enhance integration (or the clinical coordination of services) and modified productivity standards to encourage individualized job search and job development. They reduced paperwork by consolidating duplicate forms that existed internally, between the agency and mental health authority, and between the agency and vocational rehabilitation. The program leaders in at least two sites also developed databases to track outcomes and services, such as job coaching and job development, that had not been previously tracked. This enabled them to obtain additional revenue through the state vocational rehabilitation agency. These leaders were also conscientious about monitoring performance and using the data to identify implementation problems (for example, "Why are consumers losing jobs?") that otherwise would not be noticed. In addition to strong administrative skills, these program leaders also had administrative authority, which they used to set behavioral expectations (for example, number of employer contacts) and to enforce performance standards.

Several respondents commented on the importance of a program leader in implementing the evidence-based practice. For example, one respondent said, "[The program leader] made it clear if the employment specialists couldn't support the evidence-based practice then they should look for other work."

Another respondent said, "The program leader set very clear expectations for the employment specialists. There was little room for confusion as to what their job expectations were."

Furthermore, successful program leaders exhibited strong clinical supervisory skills. Site reports indicated that they understood supported employment principles and gave employment specialists real-life examples of how to apply them. They were also familiar with supported-employment clients and able to find solutions to problem cases with employment specialists. They provided positive feedback to employment specialists and rewards to clients who participated in supported employment. For example, the site with the highest fidelity score gave hats with the slogan "Everyone Works" to consumers upon entering the supported employment program.

Lack of strong leadership appeared to be a barrier to achieving high fidelity on specific items. For example, administrators at one site mandated that the supported employment staff undertake a youth work program during the summer, whereby employment specialists would find temporary, seasonal work for youths, even though this assignment was clearly at odds with supported employment principles and detracted from the staff's ability to provide high-fidelity supported employment services.

The failing site also had little support and involvement from agency administrators. Initially, it had a strong and committed program leader who facilitated early success in implementing the model, but the program leader resigned after the first year of implementation and was not replaced.

Mastery: experience versus training

All sites received a two-day training session in supported employment and also received technical assistance over at least the first year of implementation. Furthermore, consultant-trainers offered additional training as they deemed necessary. For example, three sites received extensive supervisory and management skills training, including biweekly observation of group supervision and two days of didactic training on how to supervise supported employment staff. Five sites also received job development training, including didactic training, role playing, or shadowing employment specialists on meetings with potential employers.

Reasons that four sites did not participate in additional training included a lack of need (that is, staff exhibited strong skills), lack of interest, or disruptions in staffing. Geographic distance appeared to be a factor in reduced technical assistance in two geographically remote sites.

The four highest-fidelity sites had either program leaders with prior skills in business and clinical supervision or employment specialists with strong clinical skills for working with people with mental illness. Program leaders with business skills were comfortable interacting with possible job sites and could teach and model these skills for their staff. Their understanding of business led to the quick adoption of job development activities needed for successful individualized job search and follow-along supports. In some cases, these program leaders were already part of various business networks in their local communities.

No prior specialized skills were recorded for supported employment staff in the remaining sites. In fact, the lack of business, supervisory, or clinical skills was viewed as a significant challenge.

One respondent said, "Supported employment work takes an incredible amount of skill. I think unless you have some of those skills to start with, which a place like [name withheld] that pays very little money is not going to get somebody who's very skilled at job development … plus clinical knowledge. Having those two sides come together is really what it takes, and to develop that skill if you don't have those skills at all, I think can be near to impossible … it can take a very, very long time to get their skills to that point."

Attitude: doubting recovery and supported employment principles

Staff resistance to change was common across all the sites. Some staff suspended their personal judgment and "gave the model a try." One employment specialist from one of the highest-fidelity sites admitted at the end of the project, "I didn't believe that supported employment would work with our members, but I tried it anyway. I learned that you really can't predict who will do well and who won't."

Staff resistance slowed the ability of sites to achieve full implementation of fidelity on specific elements of the model. Specifically, staff in three sites struggled with supported employment principles regarding partnering with their clients to conduct an individualized job search, searching for competitive jobs, and providing the majority of their services in the community. Supported employment staff in four sites struggled with the zero-exclusion principle and continued to offer services only to clients who they felt were "work ready." For example, survey data from a respondent at one site indicated, "Although there may not be formal criteria for exclusion, informally both case managers and supported employment staff are "screening out" clients based on hygiene, social appropriateness, substance use, and medication compliance."

The program leader confirmed the survey results by expressing concerns that "double messages" were given to case managers who were officially told to refer any client who wants to work but unofficially told that clients have to be "work ready" or they are "inappropriate referrals."

In three sites, staff who previously ran either enclave or agency-based employment programs were resistant to offering only competitive-based employment options. The mental health authority or agency administrators successfully countered the resistance by instituting and mandating procedural changes, such as removing the funding or closing access to on-site employment positions. Although staff attitudes changed in two sites once they began providing supported employment services, the resistance regained strength in one site, when the program leader resigned after one year and employment specialists slipped back into placing consumers in similar low-level job positions instead of conducting an individualized job search.

In general, agencies countered resistance by providing additional training, mandating procedural changes, or terminating or transferring the resistant employees. One site believed that training efforts were effective. For example, one respondent said, "Zero exclusion was probably the biggest thing that I think [the employment specialist] had difficulty with. And I talked to her a lot, although she was still hesitant, it wasn't until we had [an educational forum] and the other [staff] talked to her about examples … and she got it."

Three sites, however, found training to be an insufficient strategy for addressing resistance to the model. For example, one respondent said, "Not all the employment specialists are opposed to the evidence-based practice, but some of them are quite adamantly opposed to it. These employment specialists are also quite vocal and somewhat abrasive. The program leader and the clinical director approached it as an educational issue and searched for individualized, meaningful ways to influence the resistant staff members. One employment specialist that was opposed did change his practice to align with the evidence-based practice. The other did not. So this management style has not been very effective."

Furthermore, resistant staff in four sites refused training on supported employment. In one site, resistant staff successfully advocated for the cancellation of further training.

Agency administrators in three sites overcame resistance by replacing program leaders and employment specialists that advocated against the model. Sites that were able to successfully replace resistant staff with staff who embraced the evidence-based practice principles found that the turnover promoted the implementation process

As one respondent said, "This [fidelity item—that is, individualized job search] also increased because one of the primary detractors resigned from her job, thus changing the team dynamics."

And another respondent said, "[The employment specialist's] ability to take the information and have a positive attitude and go forward was critical to the success [of the supported employment program]."

Discussion

In general, the supported employment demonstration project was a success. By the end of the two-year project, eight of the nine study sites successfully implemented and sustained high-fidelity programs. However, each faced a number of similar challenges. Lessons may be learned for how those challenges were addressed and overcome.

First, the study demonstrated that nothing replaces leadership. Sites with the highest fidelity had strong leadership on both administrative and program levels. Experience from sites such as the one that ended the project with low fidelity demonstrated that although one strong program leader may be able to achieve high-fidelity temporarily, agencies need strong leadership on multiple levels to sustain high-fidelity programs over time. The depth of the qualitative data allows for a closer look at the specific roles and behaviors that effective leaders assumed on both of these levels to facilitate the implementation process.

Second, the in-depth nature of this study allowed for a fuller understanding of the intervention. In order to achieve the success, sites were not only provided structured training, they were also provided on-site and off-site technical assistance that included job shadowing and routine feedback to a wide variety of key stakeholders (employment specialists, program leaders, agency administrators, and mental health authorities). Many sites also received additional training tailored to their individual needs.

Although the intense level of training and consultation strongly influenced the implementation process, prior knowledge and experience of staff was also a key factor. Sites with the highest fidelity scores had program leaders with skills in business and clinical supervision or employment specialists with strong clinical skills. Furthermore, sites in which these skills were lacking indicated that this deficiency impeded the implementation process.

The third lesson learned is that it is essential to hire supported employment staff who believe in recovery and supported employment principles. Employing staff who doubt and challenge the evidence-based model can hinder agencies' ability to implement aspects of the model, as seen by the three sites that were unable to obtain or sustain high scores on specific fidelity items. The findings indicated that changing resistant attitudes is often difficult and training may be insufficient.

This study had several limitations. First, no consumer-level outcomes were collected, for reasons discussed by McHugo and colleagues ( 7 ). Briefly, consumer-level data collection was judged to be too resource intensive. Moreover, a number of studies have established a consistent association between higher fidelity and higher employment rates ( 17 , 18 , 19 ).

Another limitation of this report was its focus on site-specific factors. State-level factors, such as infrastructure funding, preparation, and establishing standards, are reported elsewhere ( 20 , 21 ).

Implementation monitors' involvement both in fidelity ratings and in data collection and analysis may also be viewed as a limitation. To minimize bias introduced by the dual role, two raters conducted all fidelity assessments. Across all fidelity assessments, the agreement between raters on the total scale score was excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient=.98). Implementation monitors were also instructed not to discuss fidelity ratings with sites or provide any feedback during the course of the project.

Despite these limitations, the findings provide important information about the implementation process. On the basis of these findings, we offer the following recommendations to those implementing evidence-based supported employment.

• Before initiating the supported employment implementation, ensure top-level administrators are committed to the initiative and are willing to carry out the range of actions included in this report.

• Dismantle programs that contradict or interfere with supported employment (for example, prevocational, enclave, or agency-based employment programs).

• Designate a full-time staff person to lead the supported employment program who has administrative authority. Give preference to candidates with strong skills in business and clinical supervision.

• Hire employment specialists with strong clinical skills for working with people with mental illness who believe in recovery and supported employment principles.

• Set clear performance standards based on the evidence-based model and be prepared to remove staff who do not meet them.

Conclusions

This study suggests that strong leadership on both the administrative and program levels may facilitate the implementation of supported employment. Sites with the highest fidelity scores hired staff with clinical or business skills, in addition to providing training and consultation. The findings also demonstrate that employing staff who doubt and challenge the evidence-based model slows down the implementation process, suggesting the critical role of hiring staff who believe in recovery and supported employment principles.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration under contract number 280-00-8049 with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center and through contributions from Johnson & Johnson, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health, and West Family Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR: An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:280–290, 2008Google Scholar

2. Becker DR, Drake RE: A Working Life for People With Severe Mental Illness. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

3. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

4. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

5. Lehman A, Steinwachs D: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–32, 1998Google Scholar

6. West JC, Wilk JE, Olfson M, et al: Patterns and quality of treatment for patients with schizophrenia in routine psychiatric practice. Psychiatric Services 56:283–291, 2005Google Scholar

7. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Whitley R, et al: Fidelity outcomes in the National Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatric Services 58:1279–1284, 2007Google Scholar

8. Marty D, Rapp C, McHugo G, et al: Factors influencing consumer outcome monitoring in implementation of evidence-based practices: results from the national EBP implementation project. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 35:204–211, 2008Google Scholar

9. Rapp C, Etzel-Wise D, Marty D, et al: Evidence-based practice implementation strategies: results of a qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, e-pub ahead of print, 2007Google Scholar

10. Woltmann E, Whitley R: The role of staffing stability in the implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment: an exploratory study. Journal of Mental Health 16:757–769, 2007Google Scholar

11. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: A fidelity scale for the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 40:265–284, 1997Google Scholar

12. Bond GR, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: Fidelity of supported employment: lessons learned from the National Evidence-Based Practices Project. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:300–305, 2008Google Scholar

13. Atlas.ti, Atlas, version 2.0. Berlin, Germany, GmbH, 2002Google Scholar

14. Gersick C: Time and transition in work teams: toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal 31:9–41, 1988Google Scholar

15. Eisenhardt K: Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14:532–550, 1989Google Scholar

16. Miles M, Huberman AM: Qualitative Data Analysis. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1984Google Scholar

17. Bond GR, Salyers MP: Prediction of outcome from the Dartmouth assertive community treatment fidelity scale. CNS Spectrums 9:937–942, 2004Google Scholar

18. Becker DR, Xie H, McHugo G, et al: What predicts supported employment program outcomes? Community Mental Health Journal 42:303–313, 2006Google Scholar

19. Becker DR, Smith J, Tanzman B, et al: Fidelity of supported employment programs and employment outcomes. Psychiatric Services 52:834–836, 2001Google Scholar

20. Isett KR, Burnman MA, Coleman-Beattie B, et al: The state policy context of implementation issues for evidence-based practices in mental health. Psychiatric Services 58:914–921, 2007Google Scholar

21. Rapp CA, Etzel-Wise D, Marty D, et al: Barriers to Evidence-Based Practice Implementation: Results of a Qualitative Study. Lawrence, University of Kansas, School of Social Welfare, 2007Google Scholar