Assessing Psychosocial Stressors Among Hispanic Outpatients: Does Clinician Ethnicity Matter?

Attending to culture, race, and ethnicity has become a major priority in U.S. psychiatric practice as high rates of growth of ethnic minority groups, coupled with new waves of immigrants from around the world, have resulted in an increasingly pluralistic, multiethnic society ( 1 ). Since 1980 the multiaxial format of DSM ( 2 ) has instructed clinicians to identify on axis IV any stressors that may have an impact on diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. This stemmed from decades of research on how physical illnesses and stressors create, maintain, and exacerbate psychiatric symptoms ( 3 , 4 ).

However, even though there is evidence that unique stressors affect individuals from minority groups and immigrants ( 5 , 6 ), comprehensive criteria on the objective assessment of stressors are lacking. Also lacking are guidelines on how to consider race, culture, language, ethnicity, or other background characteristics as they relate to stressors ( 7 ). Racism, discrimination, oppression, and exclusion are experienced by persons from minority groups in both flagrant and covert ways and in the interpersonal "microaggressions" of everyday life ( 8 , 9 ). Furthermore, research suggests that patients from minority groups and those from majority groups differentially reconstruct and narrate their illness experiences ( 10 ).

Adding insult to injury, interviews of Hispanic patients in English or across their language barrier usually result in their being judged more symptomatic and dysfunctional than when interviews are conducted in their mother tongue ( 11 , 12 ). Without culturally based guidelines to assess stressors, clinicians may under- or overidentify their type, number, and severity, especially across cultural divides.

Given the lack of guidance, it is no surprise that stressors are often relegated to the background. Although sociocultural factors may be crucial to both diagnosis and treatment, the "medical model" nature of the psychiatric interview often leads to an exclusionary bias in their identification ( 13 ). Stressors are often not mentioned in patients' charts and are ignored in formulations and treatment recommendations ( 14 ).

The purpose of our pilot study was to examine the impact of clinician ethnicity on the psychiatric diagnosis of Hispanic patients. We report data on axis IV.

Methods

We enrolled 88 U.S.-born or foreign-born Hispanic patients who were seeking services for the first time at an urban mental health clinic. All received an explanation of the study and provided written informed consent after being screened for capacity to provide such consent. Forty-seven clinicians participated. The study was approved by the relevant human subjects committees.

Patients were initially assessed by a Hispanic or non-Hispanic clinician. Live intakes were videotaped and viewed by a second clinician, ethnically cross-matched to the first. Both clinicians independently rendered multiaxial diagnoses and completed questionnaires about the patient and experiences during the interview. For axis IV, clinicians selected stressors from a checklist containing nine categories and examples provided in DSM-IV-TR ( 2 ).

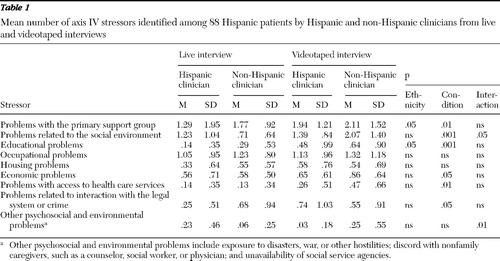

To examine the number of stressors identified, we summed each category, which produced 18 summary variables (nine for the live interview and nine for the videotaped interview). The variable "problems with the primary support group" thus had a possible range of 0–11 (11 total possible stressors were listed in the category), the variable "problems related to the social environment" had a possible range of 0–7, and so forth with the remaining categories. We computed the mean number of stressors identified by clinician ethnicity (Hispanic and non-Hispanic) and condition (live and video). Because 11 of 18 summary variables had moderate to high skewness, we used a square root transformation, which greatly improved distribution.

Controlling for clinician ethnicity and interview condition was necessary because of our design. Therefore, we created a new data set containing two records per interviewee: one with information gathered from the live interview and another with information gathered from the videotaped interview (a balanced incomplete block design with participant identification as a random effect). Using SAS Proc Mixed, we tested main effects for clinician ethnicity, interview condition, and the interaction between them. For thoroughness, we tested a negative binomial model with the untransformed data, which produced no better results than the square root transformation.

Results

The mean±SD age of the 88 patients was 41±13 years. Fifty patients (57%) were men, 71 (81%) had a high school education or more, and 80 (91%) were U.S. citizens or legal aliens. Ethnically, 32 patients (36%) were Dominican, 19 (22%) were Puerto Rican, six each (7%) were Ecuadorian or Mexican, and 24 (27%) were of other Latin American ancestry.

Of the 47 clinicians, 19 (40%) were psychiatrists, 19 (40%) were psychiatric social workers, and nine (20%) were psychologists. Thirty-one (66%) were non-Hispanic, and 32 (68%) were women. Clinicians had a mean of 10±8.7 years of experience in adult psychiatry. Clinicians differed only in the mean years of adult practice among psychiatrists; Hispanic psychiatrists had twice the mean years of non-Hispanic psychiatrists (6.81±2.87 compared with 3.00±1.65 years; p=.013).

On axis I, mood disorders were the most common diagnoses (72 patients, or 82%), followed by substance-related disorders (44 patients, or 50%), anxiety disorders (39 patients, or 44%), adjustment disorders (19 patients, or 22%), and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (13 patients, or 15%).

On axis IV, the focus of this report, clinicians identified few stressors, regardless of ethnicity or interview condition. As shown in Table 1 , the mean number of stressors identified ranged from .13 for "problems with access to health care" to 2.11 for "problems with the primary support group." Non-Hispanic clinicians consistently identified more stressors than Hispanic clinicians, regardless of condition. Clinicians who watched the videotaped interview consistently listed more stressors than clinicians who participated in the live interview, regardless of ethnicity.

|

When the analyses controlled for condition (live or video), non-Hispanic clinicians identified significantly more problems with the primary support group and educational problems than Hispanic clinicians, with no interaction effect. When the analysis controlled for ethnicity, clinicians who watched videotaped interviews identified significantly more problems than clinicians who participated in live interviews in all categories except occupational, housing, and "other" problems; only "problems related to the social environment" showed an interaction effect.

Discussion and conclusions

This study found main effects without interaction for clinician ethnicity in two axis IV categories: problems with the primary support group and educational problems. Non-Hispanic clinicians identified significantly more problems in each category than Hispanic clinicians. Our experience with Hispanic patients in general, and especially with the population the sample was drawn from, led us to anticipate that Hispanic clinicians, given their cultural proximity to patients, would have identified more stressors. One possible explanation is that non-Hispanic clinicians, precisely because of their greater cultural and linguistic distance, erred on the side of caution and cast a wider net. Non-Hispanic clinicians were also less experienced, which lends further support to the idea of their being overly cautious and thus overidentifying stressors.

Without an objective measure of actual stressors, however, we cannot assess which clinicians conducted a more thorough assessment. Overcompensation might also help to explain why clinicians watching a videotaped interview identified significantly more problems in most categories; their greater physical distance and inability to probe further may have influenced them to be overinclusive.

Education may have played a role as well. Eighty-one percent of our patient sample reported having at least a high school diploma, whereas according to 2000 data, 64% of Hispanics ages 18 to 24 had completed high school and 10% of Hispanics ages 25 to 29 had a bachelor's degree or higher ( 15 ).Because persons in our sample had higher education levels, they may have had more knowledge about their conditions or the diagnostic process or they may have been able to provide a better description of their personal history and symptoms, thereby reducing the communication distance with clinicians. Less educated patients may have faced more cognitive and intellectual challenges in communicating, which may have required more active probing by clinicians.Despite the higher education levels of our patient sample and the experience and professional diversity of our clinicians, we found significant differences in clinicians' identification of axis IV stressors.

Methodological limitations restrict the conclusiveness and generalizability of our findings. Clinician and patient samples were relatively small, which affected analytical power and our ability to balance clinicians by language, discipline, gender, or ethnicity. Imbalances also existed in interview conditions. Hispanic clinicians conducted 62 (70%) of the live interviews, and therefore non-Hispanic clinicians conducted most of the video assessments. We did not assess clinicians' cultural competence or diagnostic biases a priori and did not include an objective measure of the number and severity of stressors. Finally, assessment by videotaped interview is not common practice; however, it was necessary given the exploratory nature of our pilot study.

Our findings suggest that clinician ethnicity plays a role in the identification of stressors. Since stressors have an impact on patients' presenting problems and course of treatment, their proper identification and inclusion in clinical formulations is critical to accurate assessment, treatment planning, and service outcomes. Preliminary recommendations include training on the DSM-IV Outline for Cultural Formulation and on cultural competence. Given the deferential attitude toward authority of many Hispanic clients, clinicians should be proactive and ask directly about psychosocial and environmental stressors. Finally, the next iteration of DSM should provide more comprehensive guidelines on the inclusion of culture in assessment, clinical formulation, and treatment planning.

Future research that includes empirically based guidelines for identifying psychosocial and environmental stressors, tests the impact of these guidelines on clinicians' axis IV diagnoses, and examines the effects of addressing stressors on treatment can reduce diagnostic variability across our diverse clinician and patient populations and enhance service outcomes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The research was funded by grant R21-MH-065921 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Zayas. Manuscript preparation support was provided by the Center for Mental Health Services Research (grant P30-MH-068579), the Comorbidity and Addictions Center (grant R24-DA-013572), Social Work Training in Addictions Research (grant T32-DA-015035), and by the Center for Latino Family Research—all at Washington University in St. Louis.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Ruiz P: Addressing culture, race, and ethnicity in psychiatric practice. Psychiatric Annals 34:527–532, 2004Google Scholar

2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

3. Barnow S, Linden M, Lucht M, et al: The importance of psychosocial factors, gender, and severity of depression in distinguishing between adjustment and depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders 72:71–78, 2002Google Scholar

4. Magaña CG, Hovey JD: Psychosocial stressors associated with Mexican migrant farm workers in the Midwest United States. Journal of Immigrant Health 5:75–86, 2003Google Scholar

5. Adebimpe VR: A second opinion on the use of white norms in psychiatric diagnosis of black patients. Psychiatric Annals 34:543–551, 2004Google Scholar

6. Gee GC, Ryan A, LaFlamme DJ, et al: Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: the added dimension of immigration. American Journal of Public Health 96:1821–1828, 2006Google Scholar

7. Mazure CM, Kincare P, Schaffer CE: DSM-III-R axis IV- clinician reliability and comparability to patients' reports of stressors severity. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 58:56–64, 1995Google Scholar

8. Clark R, Anderson NB,Clark VR,et al: Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist 54:805–816, 1999Google Scholar

9. Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GFC, et al: Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist 62:271–286, 2007Google Scholar

10. Alverson HS, Drake RE, Carpenter-Song EA, et al: Ethnocultural variations in mental illness discourse: some implications for building therapeutic alliances. Psychiatric Services 58:1541–1546, 2007Google Scholar

11. Marcos LR, Alpert M, Urcuyo L, et al: The effect of interview language on the evaluation of psychopathology in Spanish-American schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 130:549–553, 1973Google Scholar

12. Malgady RG, Costantino G: Symptom severity in bilingual Hispanics as a function of clinician ethnicity and language of interview. Psychological Assessment 10:120–127, 1998Google Scholar

13. Karno M: The enigma of ethnicity in a psychiatric clinic. Archives of General Psychiatry 14:516–520, 1966Google Scholar

14. Bullock HE: Diagnosis of low-income women, in Bias in Psychiatric Diagnosis. Edited by Caplan PL, Cosgrove L. Lanham, Md, Aronson, 2004Google Scholar

15. Llagas C: Status and Trends in the Education of Hispanics. NCES 2003–2008. Washington, DC, US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2003Google Scholar