Trauma and PTSD Among Adolescents With Severe Emotional Disorders Involved in Multiple Service Systems

Over the past several decades there has been a growing awareness of the problem of trauma and its consequences throughout the lifespan. Although much attention has focused on the long-term effects of adverse experiences in childhood ( 1 , 2 , 3 ), the plight of youths exposed to trauma has also become a major concern. Rates of trauma as low as 16% have been reported among adolescents ( 4 ), although a number of other studies suggest about 40% of adolescents experience a traumatic event before age 18 ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ).

The high exposure of children and adolescents to trauma has led to efforts to evaluate its impact, including the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). General population surveys indicate 12-month prevalence rates of PTSD between .5% and 22% among youths ( 4 , 9 , 10 , 11 ). Even higher rates are reported for youths exposed to specific traumatic events, such as physical or sexual abuse ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ), or who are in particular settings, such as jails and detention centers ( 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ).

Less research has examined the prevalence of PTSD among adolescents with severe emotional and behavioral disorders. This group presents many treatment challenges because of their frequent involvement in multiple service systems (mental health, school, and juvenile justice systems), the extent of their functional impairments, their high risk for out-of-home residential placement, and their struggle to transition into adaptive adult roles ( 25 ). In response to these needs, a system-of-care model was developed to integrate fragmented services into a cohesive, family-driven, community-based system ( 26 , 27 ). Over the past decade the system-of-care model has been widely disseminated and implemented in the United States through the National Evaluation of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program, sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services ( 28 , 29 ). Grantees are required to implement a standard evaluation protocol to evaluate the outcomes of youths and their families served in the system of care. One recent study drawn from the national evaluation data reported that the rate of childhood physical or sexual abuse was 36% ( 30 ). However, the evaluation did not include measures of PTSD symptoms or diagnosis, so the extent of PTSD in this population is unknown.

Examining the rate of PTSD among youths served by multiple service systems has potentially important treatment implications. PTSD is frequently undetected in adult populations when specific screening questions are not asked ( 31 ). With the strong association between PTSD and poor psychosocial and health functioning among adolescents ( 7 , 12 , 32 , 33 , 34 ), the failure to identify and treat PTSD could increase youths' vulnerability to negative mental and physical health outcomes as they transition into adulthood, increasing their burden of chronic PTSD. To address this question, we studied the rate and correlates of PTSD among adolescents with severe emotional disorders who were enrolled in a system-of-care demonstration project in New Hampshire. The study was guided by four hypotheses. First, girls will have higher rates of PTSD than boys, consistent with gender differences in PTSD ( 35 , 36 ). Second, PTSD diagnosis will be most strongly related to history of childhood sexual abuse, consistent with previous research on youths ( 7 ) and adults ( 37 , 38 ). Third, the rate of PTSD diagnosis in the medical records of youths will be lower than the rate based on structured clinical interviews. Fourth, youths with PTSD will have a history of more treatment, more severe symptoms and behavior problems, and worse functioning than youths without PTSD.

Methods

The study took place at three community mental health centers in New Hampshire, including two serving rural areas of the state (Berlin and Littleton) and a third serving the largest city, Manchester. All three centers were implementing a system-of-care approach for youths with severe emotional disorders that was specially adapted in the state and called the Community Alliance Reform Effort (CARE NH). A regional collaborative was created in each community to coordinate and integrate planning for the local system of care. The collaborative included a regional coordinator, representatives from local service systems, consumer families, and cultural competence consultation. All youths served by CARE NH participated in an individual and family-centered process to identify and coordinate needed community services and supports ( 26 ).

Participants

Eligibility for CARE NH required that the child meet Bureau of Behavioral Health criteria for severe emotional disorder, including being under the age of 21, having an axis I DSM-IV diagnosis ( 39 ), and having severe functional impairment in more than one domain (such as school and home), as determined by the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale ( 40 ). Eligibility also required involvement with two or more state-operated systems that serve youths, including the Bureau of Behavioral Health, Bureau of Special Education, Division of Juvenile Justice Services, Bureau of Developmental Disabilities, Division of Children, Youth, and Families (child protection), Division of Substance Abuse Services, and the Bureau of Early Childhood Services. Finally, for eligibility the child had to be at risk for placement—or to have been placed—out of the home and community.

The families of all referred youths eligible for CARE NH were invited to participate in a research evaluation at baseline, which was repeated every six months for three years. Project assessments began on October 2, 2000, and ended on October 27, 2005. For youths over age ten this evaluation included an interview with both the primary caregiver and the child. Access to the CARE NH program was provided to all eligible youths and their families regardless of whether they agreed to the research. This article covers youths over age ten who participated in the research assessments. For these assessments, written informed consent for the evaluation was obtained from the caregivers and written assent was obtained from the youths. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of Dartmouth College and the state of New Hampshire.

A total of 150 adolescents were referred to CARE NH, and 118 met eligibility requirements for CARE NH. Among these eligible adolescents and their families, 70 (59%, or 47% of all referrals) agreed to participate in the research. This rate of participation compared with all referrals (eligible and not) is consistent with the 52% rate reported for all system-of-care communities in the national sample for cohort 3 (December 2004 Aggregate Data Profile Report, Macro International, Atlanta). Among the 70 youths and caregivers who participated in the research evaluation, one had incomplete information about PTSD and was dropped from subsequent analyses.

We compared the 69 research participants with the 48 nonparticipants; t tests and chi square tests were used to analyze youth characteristics (gender, age, race, living situation, involvement of specific agencies, referral source, chart diagnoses, child behavior problems, recurring health problems, history of physical abuse, and history of sexual abuse) and family characteristics (biological family history of domestic violence, mental illness, or substance abuse; parental history of psychiatric hospitalization, substance abuse treatment, or criminal conviction). None of these differences were significant, indicating that the research participants were comparable with the nonparticipants in these chararcteristics.

Measures

This study was part of the National Evaluation of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program, and all of the assessment instruments (except the Children's Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes [ChIPS], described below) were selected by Macro International, Inc., for the Center for Mental Health Services. Assessments included separate interviews with caregivers and youths.

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) ( 41 ) was completed by caregivers to measure the youth's behaviors and symptoms. The CBCL consists of two sections, including the social competence section, which taps information related to involvement in organizations, sports, peer relations, and school performance, and the behavior and emotional problems section, which taps various problems and symptoms. For statistical analyses, we used the total problems score, two broad-band syndrome scores, and eight narrow-band syndrome scores.

The Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (CAFAS) ( 40 ) was used to assess the degree to which a youth's mental disorder or substance use disorder was disruptive to daily life, based on the caregiver's report. The CAFAS uses semistructured interview questions covering eight domains of psychosocial functioning. Section V of the Behavior and Emotional Rating Scale (BERS) ( 42 ) was used to assess psychosocial functioning across dimensions of childhood strength and resiliency, based on the caregiver's report. This section includes 52 items, corresponding to interpersonal strength, family involvement, intrapersonal strength, school functioning, and affective strength subscales.

The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire (CGSQ) ( 43 ) was used to assess the extent to which the caregiver was affected by the special demands of caring for the youth over the past six months. The CGSQ contains 21 items, from which three dimensions of strain (objective, internalized subjective, and externalized subjective) and a global measure of strain were computed. Higher scores indicate greater strain.

The ChIPS ( 44 ) was used to evaluate DSM-IV disorders. The parent version was administered to caregivers, and the child version was administered to youths. The ChIPS is a structured evaluation for trained lay interviewers that yields DSM-IV diagnoses. It is reliable and valid in this population ( 45 ), including for the assessment of PTSD. For example, one study reported that PTSD diagnoses based on the ChIPS for a clinical sample of youths were strongly related ( κ =.77) to diagnoses based on the DSM-III-R Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents ( 46 ) and clinician diagnoses (sensitivity rating of 100%; specificity rating of 86%). The ChIPS also elicits information about a wide range of stressful and traumatic events, including questions to determine whether events meet DSM-IV criteria A1 (perceived threat) and A2 (distress) for PTSD. This study focused on current (past-month) PTSD diagnosis based on the ChIPS. Because trauma reports and PTSD symptoms are more often underreported than overreported among youths, resulting in discrepancies between caregivers and adolescents, we followed the procedure of scoring PTSD symptoms as present if either the caregiver or adolescent reported them ( 47 , 48 ).

Procedure

Youths were referred to CARE NH by a service provider, family member, or other involved person. Referrals were sent to the regional coordinator for the local CARE NH program at each of the three sites, who conducted an intake interview with the primary caregiver. If the youth had not been a client of the mental health center, a clinical intake also was arranged. Eligible families were then invited by the regional coordinator to participate in the research evaluation.

Families who agreed to participate provided written informed consent and were scheduled for the caregiver and youth interviews. Interviews were conducted in a location convenient for the family. Interviewees were paid for their participation. Interviewers were people who had a child with a severe emotional disorder or other service needs and who were extensively trained in conducting the interviews. Regular interviewer reliability checks were conducted throughout the project to ensure good interrater reliability.

Statistical analyses

We first examined the relationship between gender, exposure to traumatic events, and PTSD diagnosis by computing chi square analyses. We next evaluated other demographic correlates of PTSD, as well as family history, clinical history, and treatment history characteristics by computing chi square analyses and t tests. Finally, we evaluated the clinical and caregiver correlates of PTSD diagnosis by performing t tests on the CBCL, CAFAS, BERS, and CGSQ scores.

Results

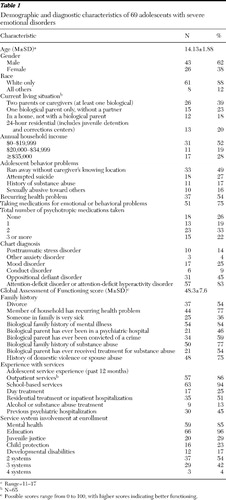

The characteristics of the remaining study sample are summarized in Table 1 .

|

Rates of trauma exposure and the prevalence of PTSD are summarized in Table 2 . Chi square tests indicated that girls were more likely to have been sexually abused than boys ( χ2 =7.32, df=1, p=.007) but showed no other differences in trauma exposure. On the basis of the ChIPS, girls were also more likely to have PTSD ( χ2 =4.56, df=1, p=.03) and to have chart diagnoses of PTSD ( χ2 =8.92, df=1, p=.003). Exposure to sexual abuse (but not other traumatic events) was associated with higher rates of PTSD according to the ChIPS, with 11 of 18 (61%) youths with sexual abuse having PTSD, compared with six of 34 (15%) youths without sexual abuse ( χ2 =12.74, df=1, p<.001).

|

Comparisons of adolescents with or without PTSD (based on the ChIPS) indicated no significant differences in any demographic characteristics other than gender but several differences in family history, behavior problems, and treatment history. Parental divorce was related to PTSD diagnosis, with 15 of 19 (79%) youths with PTSD experiencing parental divorce, compared with 22 of 50 (44%) youths without PTSD ( χ2 =6.76, df=1, p=.009). A history of having run away from home was related to PTSD, with 13 of 19 (68%) youths with PTSD having run away, compared with 20 of 48 (42%) youths with no PTSD ( χ2 =3.90, df=1, p=.05). PTSD diagnosis was significantly related to chart diagnoses of depression (nine of 19, or 47% of adolescents with ChIPS diagnosis of PTSD had chart depression diagnoses versus eight of 50, or 16% of adolescents without PTSD) ( χ2 =7.30, df=1, p=.007). Of note is that PTSD diagnosis on the ChIPS was only marginally related to a chart diagnosis of PTSD (five of 19, or 26% of adolescents with a ChIPS diagnosis of PTSD had a PTSD diagnosis in their charts, compared with five of 50, or 10% of youths without a ChIPS assessment of PTSD) (p=.08).

There were no differences in service system involvement or treatment history between the PTSD groups. However, they differed in prescribed psychotropic medications ( χ2 =8.70, df=3, p=.03). Adolescents with PTSD were more likely than those without PTSD to be prescribed medication (two of 19 youths, or 11%, versus 15 of 49, or 31%, respectively) or to be prescribed only one medication (one of 19 youths, or 5%, versus 12 of 49 or 25%, respectively) and were more likely to be prescribed two medications (ten of 19 youths, or 53%, versus 13 of 49, or 27%, respectively) or three or more medications (six of 19 youths, or 32%, versus nine of 49, or 18%, respectively).

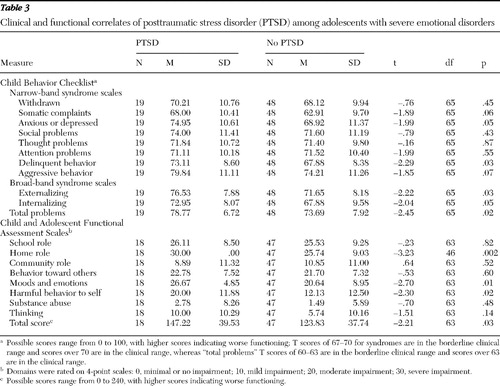

The clinical and functional correlates of PTSD on the CBCL and CAFAS are summarized in Table 3 . On the CBCL, adolescents with PTSD had higher scores on the narrow-band subscales of anxiety and depression and of delinquent behavior, and they had marginally higher scores on somatic complaints and aggressive behavior. The PTSD group also had higher scores on both broad-band syndrome subscales and on total problems. On the CAFAS, adolescents with PTSD had worse functioning in their home role, moods and emotions, and self-harming behavior, as well as on the total score.

|

None of the comparisons between the PTSD groups on the BERS or CGSQ subscales were significant. Thus PTSD was not related to caregivers' ratings of adolescents' strengths or resiliency or to caregiver strain.

Discussion

Consistent with the high rate of trauma among these youths with severe emotional disorder and multisystem involvement, the rate of PTSD was also high, at 28%. This rate exceeds general population estimates of PTSD among youths ( 4 , 9 , 10 , 11 ) and is more in line with the rates reported in studies of abused youths ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ). Also consistent with prior research, girls were more likely than boys to have a history of sexual abuse and to meet criteria for PTSD (42% versus 19%) ( 7 , 30 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ), and sexual abuse was identified as the most distressing event linked to PTSD ( 7 , 49 , 54 ).

Despite the high rate of PTSD detected by the ChIPS, it was much less frequently noted in adolescents' charts. Furthermore, the relationship between chart diagnosis of PTSD and diagnosis based on the ChIPS was only marginally significant, suggesting that PTSD was frequently not diagnosed or was misdiagnosed in the treatment settings. The only chart diagnosis that was significantly related to the interview-based diagnosis of PTSD was depression, which is often comorbid with PTSD among youths ( 7 , 12 , 18 , 33 , 49 , 55 ).

PTSD diagnosis was correlated with several important problems. Adolescents with PTSD were more likely to have a history of running away from home, consistent with prior research ( 30 , 33 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 ), and were more likely to engage in self-harming behavior, also consistent with prior research ( 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 ). PTSD also was associated with more severe behavior problems and symptoms on the CBCL, including increased anxiety or depression and increased delinquency on the narrow-band syndromes, and internalizing and externalizing symptoms on the broad-band syndromes, as well as more problems with mood and emotions on the CAFAS. These findings are consistent with research showing that PTSD among youths is associated with a wide range of symptoms and problem behaviors ( 7 , 17 , 18 , 33 , 63 ).

PTSD was also related to greater functional impairments on the CAFAS, including worse functioning at home and in school. These associations are consistent with other research on the functional correlates of PTSD among adolescents ( 12 , 33 , 53 ), as well as studies suggesting that PTSD symptoms contribute to worse functioning among youths ( 64 ). However, despite the worse clinical and psychosocial functioning of adolescents with PTSD, caregivers did not perceive them as having fewer strengths or as posing more burden.

Overall the findings suggest that PTSD is a common but underdiagnosed disorder among adolescents with severe emotional disorders. Although interview-based diagnoses of PTSD were associated with severe problems, chart diagnosis indicated that treatment providers were largely unaware of who had PTSD. The poor recognition of PTSD, combined with its more severe and heterogeneous clinical presentation, may partly account for the high rate of polypharmacy for adolescents with PTSD (88%) compared with those without PTSD (46%).

The findings have potentially important clinical implications. With the high rate of PTSD in this study and the underdiagnosis of PTSD in charts, routine screening for trauma and PTSD with standardized instruments ( 65 , 66 ) should be conducted with all adolescents receiving mental health services. In addition, mental health providers who treat youths need training in empirically validated interventions for PTSD ( 67 , 68 ). More accurate detection and treatment of PTSD among adolescents with severe emotional disorders could reduce the severe symptoms and functional impairments associated with the disorder.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the sample was not large, and we did not control for conducting multiple statistical tests, and thus some of the findings could be spurious. Second, although the racial-ethnic composition of the study sample reflected the communities where the study took place, the sample was predominantly Caucasian. Research is needed to evaluate prevalence of PTSD in a more racially and ethnically diverse population of adolescents with severe emotional disorders. Third, 41% of eligible adolescents and their caregivers declined participation in the study, suggesting that the findings may not generalize to a broader population of similar youths. Of youths with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, a significantly higher percentage participated in the research than refused. Although it is unclear why youths with these diagnoses were more likely to agree to participate in the research, the difference suggests that the findings may be more generalizable to youths with these disorders than to youths without. Fourth, the ChIPS was designed for lay interviewers, not experienced clinical interviewers. Although it has acceptable psychometric characteristics for assessing PTSD among youths ( 45 ), a more refined diagnostic instrument should be considered in future research.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study was unique in its examination of PTSD among youths with severe emotional disorders involved in multiple service systems. The findings indicated that PTSD is common but underdiagnosed, and it is associated with more severe problems and treatment with more medications. There is a need for greater awareness of the problem of trauma and PTSD among youths with severe emotional disorders.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grant SM-52915 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha T, et al: Psychosis, victimisation and childhood disadvantage: evidence from the second British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. British Journal of Psychiatry 185:220–226, 2004Google Scholar

2. Duncan RD, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, et al: Childhood physical assault as a risk factor for PTSD, depression, and substance abuse: findings for a national survey. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:437–448, 1996Google Scholar

3. Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, et al: Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance abuse disorders in women: an epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:953–959, 2000Google Scholar

4. Cuffe SP, Addy CL, Garrison CZ, et al: Prevalence of PTSD in a community sample of older adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:147–154, 1998Google Scholar

5. Boney-McCoy S, Finklehor D: Is youth victimization related to trauma symptoms and depression after controlling for prior symptoms and family relationships? A longitudinal, prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:1406–1416, 1996Google Scholar

6. Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, et al: Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:216–222, 1991Google Scholar

7. Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, et al: Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:1369–1380, 1995Google Scholar

8. Schwab-Stone ME, Ayers TS, Kasprow W, et al: No safe haven: a study of violence exposure in an urban community. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:1343–1352, 1995Google Scholar

9. Costello JE, Angold A, Burns BJ, et al: The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: goals, design, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:1129–1136, 1996Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048–1060, 1995Google Scholar

11. Seedat S, van Nood E, Vythilingum B, et al: School survey of exposure to violence and posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescents. Southern African Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health 12:38–44, 2000Google Scholar

12. Carrion VG, Weems CF, Ray R, et al: Toward an empirical definition of pediatric PTSD: the phenomenology of PTSD symptoms in youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:166–173, 2002Google Scholar

13. Deblinger E, McLeer SV, Atkins MS, et al: Post-traumatic stress in sexually abused, physically abused, and nonabused children. Child Abuse and Neglect 13:403–408, 1989Google Scholar

14. Famularo R, Fenton T, Augustyn M, et al: Persistence of pediatric post traumatic stress disorder after 2 years. Child Abuse and Neglect 20:1245–1248, 1996Google Scholar

15. Famularo R, Fenton T, Kinscherff R, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity in childhood post traumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse and Neglect 20:953–961, 1996Google Scholar

16. Lipschitz DS, Kaplan ML, Sorkenn JB, et al: Prevalence and characteristics of physical and sexual abuse among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatric Services 47:189–191, 1996Google Scholar

17. McLeer SV, Callaghan M, Henry D, et al: Psychiatric disorders in sexually abused children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:313–319, 1994Google Scholar

18. McLeer SV, Deblinger E, Henry D, et al: Sexually abused children at high risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:875–879, 1992Google Scholar

19. Seedat S, Nyamai C, Njenga F, et al: Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress symptoms in urban African schools: survey in Cape Town and Nairobi. British Journal of Psychiatry 184:169–175, 2004Google Scholar

20. Abram KM, Teplin LA, Charles DR, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:403–410, 2004Google Scholar

21. Burton D, Foy DW, Bwanausi C, et al: The relationship between traumatic exposure, family dysfunction, and post-traumatic stress symptoms in male juvenile offenders. Journal of Traumatic Stress 7:83–93, 1994Google Scholar

22. Cauffman E, Feldman SS, Waterman J, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder among female juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:1209–1216, 1998Google Scholar

23. Steiner H, Garcia IG, Matthews Z: Posttraumatic stress disorder in incarcerated juvenile delinquents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:357–365, 1997Google Scholar

24. Wasserman DA, Havassy BE, Boles SM: Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in cocaine users entering private treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 46:1–8, 1997Google Scholar

25. Burchard J, Clark R: The role of individualized care in a service delivery system for children and adolescents with severely maladjusted behavior. Journal of Mental Health Administration 17:48–60, 1990Google Scholar

26. Burns BJ, Goldman SK (Eds): Promising Practices in Wraparound for Children With Serious Emotional Disturbance and Their Families. 1998 Series, vol 4. Washington, DC, American Institutes for Research, Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice, 1999Google Scholar

27. VanDenBerg J, Grealish M: Individualized services and supports through the wraparound process: philosophy and procedures. Journal of Child and Family Studies 5:7–21, 1996Google Scholar

28. Faw L: The State Wraparound Survey, in Promising Practices in Wraparound for Children With Serious Emotional Disturbance and Their Families. 1998 Series, vol 4. Edited by Burns BJ, Goldman SK. Washington, DC, American Institutes for Research, Center for Effective Collaboration and Practice, 1999Google Scholar

29. Holden EW, Friedman RM, Santiago RL: Overview of the National Evaluation of the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Program. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 9:4–14, 2001Google Scholar

30. Walrath CM, Ybarra ML, Sheehan AK, et al: Impact of maltreatment on children served in community mental health programs. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 14:143–156, 2006Google Scholar

31. Mueser KT, Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, et al: Trauma, PTSD, and the course of schizophrenia: an interactive model. Schizophrenia Research 53:123–143, 2002Google Scholar

32. George LK, Blazer DG, Winfield-Laird I, et al: Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use in later life, in Epidemiology and Aging. Edited by Brody JA, Maddox GL. New York, Springer, 1988Google Scholar

33. Lipschitz DS, Rasmusson AM, Anyan W, et al: Clinical and functional correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder in urban adolescent girls at a primary care clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:1104–1111, 2000Google Scholar

34. Seng JS, Graham-Bermann SA, Clark MK, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical comorbidity among female children and adolescents: results from service-use data. Pediatrics 116:767–776, 2005Google Scholar

35. Olff M, Langeland W, Draijer N, et al: Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Bulletin 133:183–204, 2007Google Scholar

36. Tolin DF, Foa EB: Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: a quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Bulletin 132:959–992, 2006Google Scholar

37. Mueser KT, Goodman LA, Trumbetta SL, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493–499, 1998Google Scholar

38. Rodriguez N, Ryan SW, Van De Kemp H, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a comparison study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:53–59, 1997Google Scholar

39. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) 4th ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

40. Hodges K: CAFAS Self-Training Manual. Ann Arbor, Mich, Kay Hodges, 2000Google Scholar

41. Achenbach TM: Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, Vt, University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry, 1991Google Scholar

42. Epstein MH, Sharma JM: Behavioral and Emotional Rating Scale: A Strength-Based Approach to Assessment: Examiner's Manual. Austin, Tex, Pro-Ed Inc, 1998Google Scholar

43. Brannan AM, Heflinger CA, Bickman L: The Caregiver Strain Questionnaire: measuring the impact on the family of living with a child with serious emotional disturbance. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 5:212–222, 1998Google Scholar

44. Weller EB, Weller RA, Fristad MA, et al: Children's Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes (ChIPS). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:76–84, 2000Google Scholar

45. Fristad MA, Glickman AR, Verducci JS, et al: Study V: Children's Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes (ChIPS): psychometrics in two community samples. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 8:237–245, 1998Google Scholar

46. Reich W, Welner Z: Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents, DSM-III-R Version (DICA-R-C). St Louis, Mo, Washington University, Division of Child Psychiatry, 1988Google Scholar

47. Ford JD, Racusin R, Daviss WB, et al: Trauma exposure among children with oppositional defiant disorder and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 67:786–789, 1999Google Scholar

48. Verlhurst F, van der Ende J, Ferdinand R, et al: The prevalence of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a national sample of Dutch adolescents. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:329–336, 1997Google Scholar

49. Deters PT, Novins DK, Fickenscher A, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology: patterns among American Indian adolescents in substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 76:335–345, 2006Google Scholar

50. Deykin EY, Buka SL: Prevalence and risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder among chemically dependent adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:752–757, 1997Google Scholar

51. Elklit A: Victimization and PTSD in a Danish national youth probability sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:174–181, 2002Google Scholar

52. Ruchkin V, Schwab-Stone M, Jones S, et al: Is posttraumatic stress in youth a culture-bound phenomenon? A comparison of symptom trends in selected US and Russian communities. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:538–544, 2005Google Scholar

53. Shannon MP, Lonigan CJ, Finch AJJ, et al: Children exposed to disaster: I. epidemiology of post-traumatic symptoms and symptom profiles. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33:80–93, 1994Google Scholar

54. Silva RR, Alpert M, Munoz DM, et al: Stress and vulnerability to posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1229–1235, 2000Google Scholar

55. Roussos A, Goenjian AK, Steinberg AM, et al: Posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among children and adolescents after the 1999 earthquake in Ano Liosia, Greece. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:530–537, 2005Google Scholar

56. Cauce AM: The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents: age and gender differences. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 8:230–239, 2000Google Scholar

57. Stewart AJ, Steiman M, Cauce AM, et al: Victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among homeless adolescents. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 21:325–331, 2004Google Scholar

58. Thompson SJ: Factors associated with trauma symptoms among runaway/homeless adolescents. Stress, Trauma, and Crisis 8:143–156, 2005Google Scholar

59. Wright J, Friedrich W, Cinq-Mars C, et al: Self-destructive and delinquent behaviors of adolescent female victims of child sexual abuse: rates and covariates in clinical and nonclinical samples. Violence and Victims 19:627–643, 2004Google Scholar

60. DiClemente RJ, Ponton LE, Hartley D: Prevalence and correlates of cutting behavior: risk for HIV transmission. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30:735–739, 1991Google Scholar

61. Edgardh K, Ormstad K: Prevalence and characteristics of sexual abuse in a national sample of Swedish seventeen-year-old boys and girls. Acta Paediatrica 89:310–319, 2000Google Scholar

62. Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L: Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 72:128–140, 2002Google Scholar

63. Koenen KC, Fu QJ, Lyons MJ, et al: Juvenile conduct disorder as a risk factor for trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 18:23–32, 2005Google Scholar

64. Bolton D, Hill J, O'Ryann D, et al: Long-term effects of psychological trauma on psychosocial functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 45:1007–1014, 2004Google Scholar

65. Foa EB, Johnson KM, Feeny NC, et al: The Child PTSD Symptom Scale: a preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 30:376–384, 2001Google Scholar

66. Frederick CJ, Pynoos RS, Nader K: Childhood Post-Traumatic Stress Reaction Index. Los Angeles, University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, 1992Google Scholar

67. Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E: Treating Trauma and Traumatic Grief in Children and Adolescents. New York, Guilford, 2006Google Scholar

68. Taylor TL, Chemtob CM: Efficacy of treatment for child and adolescent traumatic stress. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 158:786–791, 2004Google Scholar