Science and Recovery in Schizophrenia

Two conceptualizations of serious mental illness—the "broken brain" and "recovery" models—have dominated recent attempts to understand and treat severe and persistent mental disorders, such as schizophrenia ( 1 , 2 ). Studies of the neurobiology of schizophrenia have identified pathological changes and mechanisms in the brain associated with vulnerability and the manifest illness ( 3 ). Research reveals that neuropathological brain changes and information-processing deficits in schizophrenia are mild preceding the onset of symptoms but worsen after acute illness and often progress with subsequent clinical episodes. These findings imply irreversible loss of brain volume and deterioration of mental functions. At the same time, a more hopeful view of the course of illness emerges from the recovery movement, which emphasizes developing a meaningful life beyond illness, and this view is supported by long-term outcome studies, which consistently show heterogeneity, with many patients improving and in some cases achieving substantial remission of illness ( 4 , 5 ).

Although these two models may seem contradictory, the Surgeon General's report on mental health ( 5 ) and the report of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health ( 6 ) attempt to bridge them. Indeed, the report of the New Freedom Commission ( 6 ), intended to be a roadmap for the mental health system, states that recovery is the "single most important goal" of people served by the mental health system and that we should "accelerate research to promote recovery." In this article, we suggest a working definition of recovery that may facilitate communication and permit a research-based synthesis of the two models. Following a brief historical overview of models for understanding schizophrenia, we discuss recent research on course and treatment in relation to recovery.

Historical background

Both neuroscience and recovery models of schizophrenia have deep historical roots. In the original conceptualization of dementia praecox by Kraepelin ( 7 ), the illness was seen as progressive and deteriorating. This pessimistic view was reinforced for many years by the limitations of existing treatments ( 8 ) and recently by research on brain abnormalities and neurodevelopmental theories of schizophrenia (summarized below). The presumption of a deteriorating course and structural brain abnormalities has sometimes fostered an attitude of therapeutic nihilism ( 9 ). The neurodevelopmental theory postulates that etiologic and pathogenic factors occur long before the onset of the illness (probably in gestation), disrupt the course of normal neural development, and produce alterations of specific neural circuits that confer vulnerability and ultimately lead to biological and psychosocial malfunction ( 10 , 11 , 12 ). According to this view, once the neurodevelopmental diathesis of schizophrenia has been established, the illness runs an inexorable course.

Kraepelin's pessimistic view and circular reasoning (that is, course was used to determine diagnosis) were challenged by Bleuler ( 13 ), who observed that patients with apparent dementia praecox constituted a heterogeneous "group of schizophrenias" with highly variable outcomes. He noted that some patients' symptoms remitted substantially or even completely, with return to normal functioning, and that the modal course was one of eventual improvement, which he termed "healing with scarring." Since Bleuler's early observations, the evidence from numerous long-term follow-up studies has supported this heterogeneity, the capacity for symptomatic remission and functional improvement early in the course of the illness, and also, though less completely, improvements in later life ( 14 , 15 , 16 ). Mental health advocates have embraced the longitudinal research as evidence of the potential for recovery.

Defining recovery

Much of the tension between neuroscientists' emphasis on brain pathologies and mental health advocates' emphasis on recovery appears to arise from the lack of definitional clarity. Recovery has been defined in literally dozens of ways ( 17 ). Neuroscientists, on the one hand, often assume that recovery connotes the complete absence of disease or a cure. Even current studies of outcome and recovery tend to emphasize returns to normal function ( 8 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ). Advocates, on the other hand, often use recovery to describe a process of managing one's mental illness, moving beyond its devastating psychological effects, and pursuing a personally meaningful life in the community ( 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ). This latter meaning involves hope, motivation, personal responsibility, the pursuit of individual goals, and participation in community life, but not necessarily the absence of symptoms. Recovery in this more complex sense implies certain types of outcomes and treatments but is also connected to civil rights, stigma, self-help, opportunities, and other community concepts that are much broader than usual definitions of illness and level of functions of the health care system. Davidson and colleagues ( 31 ) offered the simple but useful clarification that neuroscientists are describing recovery "from" illness, which implies cure, whereas advocates are describing recovery "in" illness (that is, being "in recovery"), which refers to moving ahead with one's life, often despite persistent symptoms.

Given the protean definitions of recovery and the potential for miscommunication, how can we understand and discuss the links between science and recovery? One possible solution, which we do not endorse, would be to avoid the term recovery entirely as another unhelpful piece of mental health jargon. This path would ignore the power and value of the term for consumers and providers and would fail to respond to the New Freedom Commission's recognition of the importance of recovery and its call for research on this concept. We therefore propose an alternative path of definitional specificity and consistency based on using qualifying terms for recovery. Because the meaning of recovery lacks precision (and thus promotes ambiguity and confusion), we propose using standard qualifiers—for example, "recovery of cognitive functioning" or "recovery of vocational functioning"—to signify improvements in specific areas. The danger remains that some will read recovery as implying complete cure, but we endorse the current emphasis on improvement, which realistically emphasizes states of partial cure. The emphasis on a range of improvements in specific areas should allow us to communicate more clearly regarding the current findings and goals of research. We also acknowledge that civil rights, stigma, housing, vocational opportunities, and other community issues are relevant to the recovery movement and extremely important to those with disabilities but are generally outside the scope of the psychiatric research reviewed here.

Natural history of schizophrenia and recovery

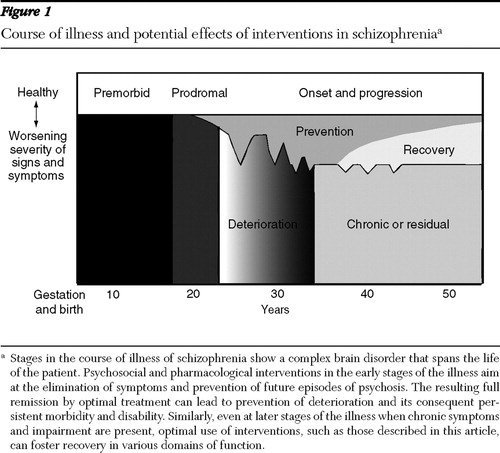

Schizophrenia is a complex brain disorder that spans the life course ( Figure 1 ). Although the etiology is uncertain, current evidence indicates that polygenic factors combine with a variety of environmental insults—including intrauterine stressors (for example, malnutrition and infection), birth complications, and postnatal factors (for example, psychoactive drug use)—to influence and perturb neurodevelopment and enhance the vulnerability to develop the heterogeneous disorder that we call schizophrenia ( 3 ). Although the disorder has been defined for the past century primarily in terms of psychotic symptoms, schizophrenia more recently has been characterized in terms of brain abnormalities and other symptom dimensions, such as negative symptoms and impairments in neurocognitive functioning in addition to psychosis ( 9 , 32 ).

Neurobiology

The evidence for neurobiological abnormalities underlying schizophrenia is robust. Several susceptibility genes for schizophrenia have been identified and replicated, with evidence rapidly emerging of the functional significance of allelic variation, mutations, and copy number variation ( 33 , 34 ). These genes give rise to the (intermediate) phenotype, or observable aspects, of the illness ( 35 , 36 ). Neuroimaging research has demonstrated decreased gray matter volume in the cerebral cortex, reduced volumes of the hippocampus and thalamus, and enlarged lateral and third ventricles and subarachnoid space ( 37 , 38 , 39 ). Studies of brain function using neuroimaging, electrophysiology, and cognitive tests have also consistently found evidence of hypofunctioning in specific tasks mediated by the frontal and temporal lobes ( 40 ) and of diminished perfusion or activation on measures of positron-emission tomography or functional magnetic resonance imaging ( 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ). At the same time, studies of sensory gating among patients with schizophrenia show deficiencies in the normal inhibitory mechanisms that help to manage modulation of various sensory inputs ( 47 , 48 , 49 ). Milder forms of these biological abnormalities appear to be present at the onset of overt psychotic illness and may be present premorbidly, with areas of cognitive dysfunction carrying implications for brain localization, as well as for greater specificity for cognitive remediation interventions ( 50 ).

Progressive structural pathology may occur with additional psychotic episodes, at least for a subgroup of patients ( 51 ), leading to the current hypothesis that active psychosis can be neurotoxic ( 9 ). Some patients clearly demonstrate further deterioration of brain structure and cognitive function over time ( 52 ). The natural age-dependent attrition of dopamine activity may also explain why positive symptoms tend to decrease over time and in later life ( 53 ).

Importantly, all of these studies show a range of findings from little or no differences through extreme abnormalities relative to persons without the disorder. The large number of genes and types of environmental insults involved in etiology almost certainly underlie the extreme heterogeneity of brain abnormalities and of vulnerabilities, although these relationships are not yet well understood.

Psychotic symptoms

Many people experience psychotic symptoms (for example, in relation to drug use or trauma), but only a small proportion experience severe disturbances that endure for months and thus meet the criteria for schizophrenia ( 54 ). Although a substantial proportion of individuals experience a full remission of psychotic symptoms, few fully recover without recurrences. It is unclear if this is due to the recurrent and progressive nature of the illness, to the limitations of our treatments, or to problems with access to and delivery of clinical care. On the other hand, only a minority of patients fail to respond to treatment and remain severely psychotic for many years after their first episode. Although the early phase of illness is characterized by positive symptoms of psychosis, each successive episode of psychosis may bring less resolution of positive symptoms and an increasing prominence of negative symptoms, which often become enduring. Positive symptoms tend to diminish in intensity in the fifth and sixth decades of life ( 53 , 55 ).

Cognitive symptoms

There is increasing recognition that cognitive symptoms (also termed neuropsychological or neurocognitive deficits related to abnormalities in perception and information processing) constitute a more persistent dimension of the illness and one that more directly and permanently limits functioning ( 32 , 56 , 57 ). Subtle cognitive and academic performance differences between individuals who do not develop schizophrenia and future schizophrenia patients emerge in childhood and precede the onset of formal signs of the illness, but these are not outside the normal range ( 58 , 59 , 60 ). At the time of the first psychotic episode, most patients appear to sustain a further decrement in cognitive functioning ( 61 ). There is little or no evidence for natural improvements in cognitive symptoms over time, and some elderly patients may gradually worsen over time ( 52 ).

Psychosocial functioning

Functional behaviors, such as living independently in the community, working competitively, and developing social and intimate relationships, have been studied for at least a century with several consistent findings. First, functional capacity is highly variable among persons with schizophrenia, but it shows some continuity over time ( 13 , 62 , 63 ). Some people have premorbid functioning in the normal range, whereas others show prolonged poor levels of function or severe deterioration in functioning before the onset of overt illness; these differences were the basis for the theory of good and poor prognosis and the theory of process and nonprocess schizophrenia ( 64 ) and more recently for concepts of deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia ( 56 , 65 ).

Second, for persons with schizophrenia, functioning in adult roles is strongly affected by environmental opportunities, supports, stimulation, and stigma. Stigma works its ill effects in ways that are hard to quantify, but it produces a major impact on opportunities for normative life and for self-esteem and morale. During the era of long-term hospitalization, for example, patients with schizophrenia experienced profound atrophy of social, vocational, and basic living skills as a result of prolonged isolation and exposure to neglectful, stultifying conditions ( 66 , 67 ), which as iatrogenic effects may have reinforced false beliefs about intrinsic deterioration. Conversely, affording people opportunities to develop in social and vocational ways engenders optimism and better functioning ( 68 , 69 ). International studies by the World Health Organization show that patients with schizophrenia experience better functional outcomes in agrarian societies or developing economies with greater family and social supports, simpler vocational roles, and less stigma regarding the illness ( 70 ).

Third, functional performance in schizophrenia has a highly variable course, with substantial restoration of psychosocial functioning after initial episodes, increasing deterioration following subsequent episodes, and the potential for some degree of functional improvement in later life ( 69 ). The evidence that many people with schizophrenia improve in social and vocational functioning over time is counterbalanced by the evidence that many others suffer sustained disability, high rates of institutionalization in nursing homes, and excessive medical morbidity and mortality ( 71 , 72 , 73 ). In the United States, people with schizophrenia die approximately 25 years earlier than others in the general population, and the majority of older people with schizophrenia are not living independently in the community.

The magnitude of effects has been small to moderate from a host of variables thought to influence behavioral function in schizophrenia, including gender, birth trauma, age at onset, mode of onset, premorbid adjustment, intelligence, severity of symptoms, neurocognitive deficits, and severity of abnormal brain morphology ( 62 , 63 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 ). However, recent research shows that cognitive impairments probably have the strongest associations with functional outcomes ( 32 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 ) and predict an estimated 40% of the variance ( 83 ), far more than any other domain ( 32 ).

Quality of life

Quality of life encompasses many of the same concepts as current multifaceted views of recovery ( 84 ). Quality of life refers to the nonillness aspects of the person's life and generally includes subjective views of physical health status, functional ability, psychological status and well-being, social interactions, and economic status ( 85 ). In mental health research, quality-of-life measures also address satisfaction with life, functioning in daily activities and social roles, personal preferences regarding goals, living conditions, safety, environmental restrictions, finances, and opportunities ( 84 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 ). Although quality of life has many of the same problems of nonspecificity as the concept of recovery, it offers the advantages of clear communication and harmony with other areas of medicine faced with the same challenges.

Mental health research shows that patients with schizophrenia report worse quality of life than the general population and than those with physical illnesses; that younger, female, married, and less educated patients report higher quality of life; that length of illness correlates with lower quality of life; and that more symptoms, especially negative and cognitive symptoms, are related to lower quality of life ( 90 ). In general, subjective quality of life is related to the discrepancy between circumstances and expectations, which probably explains the inverse relationship with education. Many psychological constructs, such as self-esteem and self-efficacy, are considered to be mediating variables in models of quality of life ( 89 ).

Self-agency

The concept of recovery clearly extends beyond quality of life to encompass a process of assuming self-agency by developing hope, taking responsibility for one's life, participating actively in one's treatment, managing one's illness, and defining and pursuing personally meaningful goals. These issues have been described extensively in the recovery literature ( 26 , 27 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 ).

Intervention research and recovery

Recovery of biological functions

Several lines of evidence are beginning to show that biological functions in the brain can improve with treatment among adults with schizophrenia. Recent studies of nicotinic agonists have been reported to improve sensory gating ( 95 ), and dopamine agonists have been found to enhance frontal cortical blood flow and metabolism ( 96 ). In addition, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and some antipsychotics have been found to promote growth in neural and glial cells ( 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 ). Moreover, clinical studies have shown that administration of selective mood stabilizers (for example, lithium) and antipsychotics (for example, clozapine-like second-generation drugs) can attenuate the loss or increase the volume of brain gray matter ( 101 , 102 , 103 ). Recent research also suggests that at the cellular level medications improve neurochemical function and that learning-based interventions, such as cognitive training, may also improve neural connectivity ( 104 ).

Recovery from psychosis

Interventions during the early phase of psychosis aim to eliminate symptoms completely (full remission) and prevent future episodes of psychosis. For the majority of first-episode patients, antipsychotic medications and evidence-based psychosocial treatments can achieve full or substantial remission of positive symptoms ( 105 ). Elimination of negative symptoms is much less clear. Combinations of current medications and psychosocial interventions can prevent future episodes of psychosis in most cases, but only if patients continue to receive treatment. Approximately 90% of patients will have at least one psychotic relapse within five years ( 106 ), partially because of high attrition rates from treatment, failure to implement evidence-based interventions, and the limitations of available therapeutics.

In general, medications are less effective for patients with chronic schizophrenia than for those with first-episode or early-stage schizophrenia. Combining psychosocial interventions (such as assertive community treatment, family psychoeducation, adherence interventions, social skills training, and relapse prevention techniques) with medications has an additive effect on relapse prevention ( 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 ). Cognitive-behavioral interventions can also reduce the functional impact of residual positive psychotic symptoms, as well as diminish negative symptoms ( 109 , 112 ). The combination of optimal psychosocial and pharmacological intervention for management of symptoms has been termed "illness management and recovery" ( 109 ).

Recovery of cognitive functions

Cognitive symptoms are rarely, if ever, eliminated when present at the onset of illness and the initial episode of psychosis. Although researchers have just started to target cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia, initial studies suggest that specific cognitive symptoms can be reduced (not eliminated) by second-generation antipsychotic medications ( 113 , 114 ), by cognitive retraining ( 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 ), and perhaps by supportive psychotherapy ( 110 ).

Improvements in existing cognitive symptoms, although modest, may at some point become sufficient to improve more complex functional behaviors, such as social, educational, and vocational functioning ( 110 , 115 , 119 , 120 , 121 ). Functional magnetic resonance imaging data suggest that cognitive rehabilitation programs may even change the way the brain processes information ( 116 ). Improvements in cognition lead to immediate benefits, such as increased learning potential ( 83 ), social cognition ( 122 ), and functional capacity ( 123 , 124 , 125 ); longer-term effects on cognitive functions remain to be demonstrated.

Recovery of functional capacity

Psychiatric rehabilitation targets specific behavioral functions, such as independent living, competitive employment, education, family relationships, and social relationships ( 107 , 126 , 127 ). Effective interventions include skills training, psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapies, cognitive enhancement therapies, and a variety of supports within and around normative community settings ( 5 , 6 , 121 , 128 , 129 , 130 ). Medications alone do not have a direct impact on behavioral functional performance but may facilitate participation in psychiatric rehabilitation ( 131 ).

Research shows that independent living is a realistic goal for the great majority of individuals with schizophrenia. Supported housing and "housing first" approaches have demonstrated that most persons with schizophrenia (over 90%) can live in independent housing, without requiring stepwise progression through a continuum of group homes and without requiring participation in mental health treatment, provided they have supports ( 132 , 133 ). This capacity for independent community living includes individuals who are chronically homeless and mentally ill. For the small minority of patients with schizophrenia who cannot live independently, substance abuse and comorbid medical conditions, rather than mental illness, seem to be the critical barriers ( 134 , 135 ).

Competitive employment and education in routine community settings also appear to be realistic and beneficial goals for most people with schizophrenia. Supported employment, which provides supports for finding jobs that match persons' interests and for maintaining employment, has robust empirical support ( 128 , 136 , 137 ). Supported employment is also effective for patients with severe disabilities and for those with comorbid conditions ( 128 ). Although 70% or more of participants in supported employment can achieve competitive employment, nearly all work part-time, and very few people entirely stop receiving disability payments ( 128 ). Limitations in the success of supported employment appear to be due to some combination of cognitive deficits and disincentives in the insurance and benefits systems ( 138 , 139 ). For example, patients who are working full-time can lose their health insurance and not be able to obtain insurance through employment. Supported education has received minimal research attention compared with supported employment, but it follows the same principles, uses similar techniques, and is often combined with supported employment ( 140 ). Helping people with schizophrenia return to work or school early in the course of illness, rather than after disability has been established for years, appears to be even more effective ( 141 , 142 ).

The research on improving social relationships is considerably more complicated. Social skills training helps to improve specific social behaviors among patients with schizophrenia, and some transfer of these skills occurs from the training setting to patients' day-to-day lives ( 143 , 144 ). Nevertheless, after more than 40 years of research, social skills training remains controversial because the magnitude of effects on social performance behaviors in routine community settings remains uncertain. Recent efforts to include in vivo practice and to involve natural supports in reinforcing social skills are promising ( 145 , 146 ). Although many other approaches to helping people with schizophrenia achieve their social goals are commonly used and show promise (for example, consumer-run social programs, supported socialization, recovery centers, and clubhouses), they have not been studied rigorously ( 147 ).

One area of social performance that has been studied separately is family relationships. Family psychoeducation programs of several types consistently decrease negative emotional expression and conflict within families and thus improve family relationships ( 148 ). This has generally been attributed to changing the family unit's behavior rather than the individual patient's social behaviors.

As research has clarified the importance of cognitive deficits in relation to performance behaviors, researchers have shown that cognitive training ( 121 ) and environmental adaptation and compensation ( 149 ) can improve performance behaviors in a variety of settings. How much these efforts will add to standard supported education, supported employment, and social skills training is as yet unclear.

Recovery of quality of life

In general, treatment improves subjective quality of life among people with schizophrenia through its effects on other outcomes (for example, symptoms and cognition). Interventions that improve symptom control without increasing side effects and those that improve functional behaviors also improve subjective quality of life ( 90 ). Quality of life is consistently increased by interventions such as supported employment that lead to better vocational functioning and better incomes ( 150 , 151 , 152 ).

Recovery of self-agency

As noted above, the recovery concept goes beyond quality of life as an outcome to also emphasize an active process of self-agency: developing hope, taking charge of one's life, and pursuing one's personal goals. Psychiatric rehabilitation has emphasized these issues, including personal goal attainment, for many years ( 153 ). Current research includes several effective approaches that improve motivation and self-management of illness, such as education, behavioral tailoring, and cognitive-behavioral interventions ( 109 ). In addition, current psychotherapies ( 154 ), self-help programs ( 155 ), and peer-directed medication management ( 156 ) emphasize the process of hope and taking responsibility. As yet, however, controlled research on these approaches has not been conducted ( 157 ).

Discussion

In this first decade of the 21st century, intervention research supports the New Freedom Commission's ( 6 ) call for research on the multifaceted concept of recovery. As reviewed above, researchers are making progress in understanding and improving various aspects of brain function, symptom control, cognitive function, psychosocial behaviors, quality of life, and self-agency. In most of these areas, effective interventions exist, and within each area a number of promising interventions are under investigation.

Several findings are clear. People with schizophrenia are tremendously heterogeneous in each domain of recovery, and the various domains of recovery are themselves relatively independent from one another. Current interventions are effective for specific dimensions of the illness and functions, are usually ameliorative rather than curative, and are effective only for a proportion of patients. Hence, we suggest defining recovery in terms of improvements in specific domains rather than globally.

The limitations of current research on recovery are also apparent. First, a consistent and more specific terminology is needed to facilitate communication among advocates, researchers, and policy makers. Second, because our knowledge of the neurobiology, pathophysiology, and heterogeneity of schizophrenia is incomplete, definitive interventions are lacking. In the immediate future, interventions are likely to be restorative for some patients, ameliorative for most, and ineffective for some others. Third, because the dissemination and adoption of effective treatments lag far behind their development (Drake RE, Skinner JS, personal communication, 2008), the great majority of patients with schizophrenia will probably not have access to evidence-based interventions until there is extensive reform of health care and disability policies in the United States.

Conclusions

Neuroscience, clinical and services research, and the recovery movement are addressing the same important issues in regard to schizophrenia, albeit in different ways ( 5 , 6 ). Research might be seen as more relevant and advocacy might be seen as more effective if the two groups could adopt a more precise, uniform terminology and work collaboratively. We have suggested a simple modification of terms to foster collaboration and have illustrated how such language might be useful in clarifying areas and degrees of progress, as well as areas in which we are in need of more intensive research.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Lieberman has received research grants from, served as a consultant for, served on the advisory board for, or served on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Forest Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Pfizer, Solvay, and Wyeth. Dr. Lieberman also holds a patent with RepliGen Corporation. Dr. Lieberman does not receive financial compensation or salary support for being a consultant or for being on an advisory board. Dr. Keefe has received research grants from, served as a consultant for, or received speaker's honoraria from Abbott Laboratories, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharm, Eli Lilly and Company, Gabriel Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Orexigen Therapeutics, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and XenoPort. Dr. Keefe also receives royalties from the Brief Assessment of Cognition Symbol Coding of the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery. Dr. Perkins has received research grants, consulting fees, or educational fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, and Shire Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Stroup has served as a consultant for or has received speaker's honoraria from AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, and Solvay Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Andreasen N: The Broken Brain. New York, Harper and Row, 1984Google Scholar

2. Jacobson N: In Recovery. Nashville, Tenn, Vanderbilt University Press, 2004Google Scholar

3. Lewis DA, Lieberman JA: Catching up on schizophrenia: natural history and neurobiology. Neuron 28:325–334, 2000Google Scholar

4. Eack SM, Keshavan MS: Foresight in schizophrenia: a potentially unique and relevant factor to functional disability. Psychiatric Services 59:256–260, 2008Google Scholar

5. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

6. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

7. Kraepelin E: Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia, 8th German ed. Translated by Barclay RM, Robertson GM. Edinbrugh, Livingston, 1919Google Scholar

8. Hegarty JD, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, et al: One hundred years of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the outcome literature. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1409–1416, 1994Google Scholar

9. Lieberman JA: Is schizophrenia a neurodegenerative disorder? A clinical and neurobiological perspective. Biological Psychiatry 46:729–739, 1999Google Scholar

10. Weinberger DR: Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:660–669, 1987Google Scholar

11. Murray RM, Lewis SW: Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? British Medical Journal 295:681–682, 1987Google Scholar

12. Freedman R, Coon H, Myles-Worsley M, et al: Linkage of a neurophysiological deficit in schizophrenia to a chromosome 15 locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 94:587–592, 1997Google Scholar

13. Bleuler E: Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias. New York, International Universities Press, 1911Google Scholar

14. McGlashan T: A selective review of North American long-term follow-up studies of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 14:515–542, 1988Google Scholar

15. Lieberman JA, Perkins D, Belger A, et al: The early stages of schizophrenia: speculations on pathogenesis, pathophysiology and therapeutic approaches. Biological Psychiatry 50:884–897, 2001Google Scholar

16. Bradford D, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA: Pharmacological management of first-episode schizophrenia and related non-affective psychoses. Drugs 63:2265–2283, 2003Google Scholar

17. Onken SJ, Craig CM, Ridgway P, et al: An analysis of the definitions and elements of recovery: a review of the literature. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:9–22, 2007Google Scholar

18. Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, et al: The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness: II. long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:727–735, 1987Google Scholar

19. Harrow M, Sands JR, Silverstein ML, et al: Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:287–303, 1997Google Scholar

20. Carpenter WT Jr, Strauss JS: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: IV. eleven-year follow-up of the Washington IPSS cohort. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:517–525, 1991Google Scholar

21. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, et al: Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:473–479, 2004Google Scholar

22. Resnick SG, Rosenheck RA, Lehman AF: An exploratory analysis of correlates of recovery. Psychiatric Services 55:540–547, 2004Google Scholar

23. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, et al: Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:256–272, 2002Google Scholar

24. Bond GR, Salyers M, Rollins A, et al: How evidence-based practices contribute to community integration. Community Mental Health Journal 40:569–588, 2004Google Scholar

25. Xie H, McHugo GJ, Helmstetter B, et al: Three-year outcomes of patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and co-occurring substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Research 75:337–348, 2005Google Scholar

26. Mead S, Copeland ME: What recovery means to us: consumer perspectives. Community Mental Health Journal 36: 315–328, 2002Google Scholar

27. Peyser H: What is recovery? A commentary. Psychiatric Services 52:486–487, 2001Google Scholar

28. Deegan PE: Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11:11–19, 1988Google Scholar

29. Deegan PE: Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:91–97, 1996Google Scholar

30. Young SL, Ensing DS: Exploring recovery from the perspective of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:219–231, 1999Google Scholar

31. Davidson L, Tondora J, Lawless MS, et al: A Practical Guide to Recovery-Oriented Practice: Tools for Transforming Mental Health Care. New York, Oxford University Press, in pressGoogle Scholar

32. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321–330, 1996Google Scholar

33. Lewis CM, Levinson DF, Wise LH, et al: Genome scan meta-analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, part II: schizophrenia. American Journal of Human Genetics 73:34–48, 2003Google Scholar

34. Elkin A, Kalidindi S, McGuffin P: Have schizophrenia genes been found? Current Opinion in Psychiatry 17:107–113, 2004Google Scholar

35. Adler LE, Freedman R, Ross RG, et al: Elementary phenotypes in the neurobiological and genetic study of schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 46:8–18, 1999Google Scholar

36. Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR: Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Molecular Psychiatry 10:40–68, 2005Google Scholar

37. Lawrie SM, Abukmeil SS: Brain abnormality in schizophrenia: a systematic and quantitative review of volumetric magnetic resonance imaging studies. British Journal of Psychiatry 172:110–120, 1998Google Scholar

38. McCarley RW, Wible CG, Frumin M, et al: MRI anatomy of schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 45:1099–1119, 1999Google Scholar

39. Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, et al: A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 49:1–52, 2001Google Scholar

40. Ford JM, Roth WT: Deficient response modulation of event-related brain potentials in schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 17:91–96, 2004Google Scholar

41. Bertolino A, Blasi G, Caforio G, et al: Functional lateralization of the sensorimotor cortex in patients with schizophrenia: effects of treatment with olanzapine. Biological Psychiatry 56:190–197, 2004Google Scholar

42. Snitz BE, MacDonald A III, Cohen JD, et al: Lateral and medial hypofrontality in first-episode schizophrenia: functional activity in a medication-naïve state and effects of short-term atypical antipsychotic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:2322–2329, 2005Google Scholar

43. Molina V, Sanz J, Reig S, et al: Hypofrontality in men with first-episode psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry 186: 203–208, 2005Google Scholar

44. Riehemann S, Volt HP, Stutzer P, et al: Hypofrontality in neuroleptic-naïve schizophrenic patients during the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test—a fMRI study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 251:66–71, 2001Google Scholar

45. Davidson LL, Heinrichs RW: Quantification of frontal and temporal lobe brain-imaging finding in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research 122:69–87, 2003Google Scholar

46. Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Flaum M, et al: Hypofrontality in schizophrenia: distributed dysfunctional circuits in neuroleptic-naïve patients. Lancet 349:1730–1734, 1997Google Scholar

47. Ford JM, Gray M, Whitfield SL, et al: Acquiring and inhibiting prepotent responses in schizophrenia: event-related brain potentials and functional magnetic resonance imaging. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:119–129, 2004Google Scholar

48. Braff DL, Geyer MA: Sensorimotor gating and schizophrenia: human and animal model studies. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:181–188, 1990Google Scholar

49. Freedman R, Adler LE, Gerhardt GA, et al: Neurobiological studies of sensory gating in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:669–678, 1987Google Scholar

50. Erlenmeyer-Kimling L, Cornblatt B: High-risk research in schizophrenia: a summary of what has been learned. Journal of Psychiatric Research 21:401–411, 1987Google Scholar

51. Steen RG, Mull C, McClure R, et al: Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. British Journal of Psychiatry 188:510–518, 2006Google Scholar

52. Harvey PD, Lombardi J, Leibman M, et al: Cognitive impairment and negative symptoms in geriatric chronic schizophrenic patients: a follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research 22:223–231, 1996Google Scholar

53. Lieberman JA, Mailman R: Decline of dopamine: effects of age and acute neuroleptic challenge. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:319–323, 1998Google Scholar

54. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

55. Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, et al: Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1080–1086, 1998Google Scholar

56. Freedman R, Adams CE, Adler LE, et al: Inhibitory neurophysiological deficit as a phenotype for genetic investigation of schizophrenia. American Journal of Medical Genetics 97:58–64, 2000Google Scholar

57. Heinrichs RW: The primacy of cognition in schizophrenia. American Psychologist 60:229–242, 2005Google Scholar

58. David AS, Malmberg A, Brandt L, et al: IQ and risk for schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study. Psychological Medicine 27:1311–1323, 1997Google Scholar

59. Fuller R, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, et al: Longitudinal assessment of premorbid cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia through examination of standardized scholastic test performance. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1183–1189, 2002Google Scholar

60. Davidson M, Reichenberg A, Rabinowitz J, et al: Behavioral and intellectual markers for schizophrenia in apparently healthy male adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1328–1335, 1999Google Scholar

61. Bilder RM, Goldman RS, Robinson D, et al: Neuropsychology of first-episode schizophrenia: initial characterization and clinical correlates. American Journal Psychiatry 157:549–559, 2000Google Scholar

62. Gurel L, Lorei TW: Hospital and community ratings of psychopathology as predictors of employment and readmission. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 39:286–291, 1972Google Scholar

63. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT Jr: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia, II. Archives of General Psychiatry 31:37–42, 1974Google Scholar

64. Vaillant GE: Prospective prediction of schizophrenic remission. Archives of General Psychiatry 11:509–518, 1964Google Scholar

65. Carpenter WT Jr, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AM: Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:578–583, 1988Google Scholar

66. Goffman E: Asylums. Garden City, New York, Anchor Books, 1961Google Scholar

67. Wing JK, Brown GW: Institutionalism and Schizophrenia. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1970Google Scholar

68. Bond GR, Resnick SG, Drake RE, et al: Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:489–501, 2001Google Scholar

69. Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, Committee on Psychopathology: Beyond Symptom Suppression: Improving Long-Term Outcomes of Schizophrenia. Report no 134. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

70. Hopper K, Wanderling J: Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative followup project. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:835–846, 2000Google Scholar

71. Bartels SJ, Van Citters AD: Community-based alternatives for older adults with serious mental illness: the Olmstead decision and deinstitutionalization of nursing homes. Ethics, Law, and Aging Review 11:3–22, 2005Google Scholar

72. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW: Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventing Chronic Disease 3:1–14, 2006Google Scholar

73. Steadman HJ, Deane MW, Morrissey JP, et al: A SAMHSA research initiative assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 50:1620–1623, 1999Google Scholar

74. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT Jr: Prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: III. five-year outcome and its predictors. Archives of General Psychiatry 34:159–163, 1977Google Scholar

75. McGlashan TH: Predictors of shorter-, medium-, and longer-term outcome in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:50–55, 1986Google Scholar

76. Shepherd M, Watt D, Falloon I, et al: The natural history of schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study of outcome and prediction in a representative sample of schizophrenics. Psychological Medicine: Monograph Supplement 15:1–46, 1989Google Scholar

77. Salyers ML, Curran PJ, Mueser KT: Factor structure and construct validity of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Psychological Assessment 8: 269–280, 1996Google Scholar

78. Brekke JS, Raine A, Ansel M, et al: Neuropsychological and psychophysiological correlates of psychosocial functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23: 19–28, 1997Google Scholar

79. Brekke JS, Kohrt B, Green MF: Neuropsychological functioning as a moderator of the relationship between psychosocial functioning and the subjective experience of self and life in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:697–708, 2001Google Scholar

80. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Harvey PD, et al: Cognitive and symptom predictors of work outcomes for clients with schizophrenia in supported employment. Psychiatric Services 54:1129–1135, 2003Google Scholar

81. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY: The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 45:175–184, 2000Google Scholar

82. McGurk SR, Moriarty PJ, Harvey PD, et al: The longitudinal relationship of clinical symptoms, cognitive functioning and adaptive life in geriatric schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 42:47–55, 2002Google Scholar

83. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, et al: Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the "right stuff"? Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:119–136, 2000Google Scholar

84. Katschnig H: How useful is the concept of quality of life in psychiatry? in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 2006Google Scholar

85. Spilker B: Quality of Life Assessments in Clinical Trials. New York, Raven Press, 1990Google Scholar

86. Angermeyer MC, Kilian R: Theoretical models of quality of life for mental disorders, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 2006Google Scholar

87. Freeman HL: "Standard of living" and environmental factors as a component of quality of life in mental disorders, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 2006Google Scholar

88. Wiersma D: Role functioning as a component of quality of life in mental disorders, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 2006Google Scholar

89. Zissi A, Barry MM: Well-being and life satisfaction as components of quality of life in mental disorders, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 2006Google Scholar

90. Bobes J, Garcia-Portilla MP: Quality of life in schizophrenia, in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders, 2nd ed. Edited by Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 2006Google Scholar

91. Jacobson N, Greenley D: What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services 52:482–487, 2000Google Scholar

92. Lovejoy M: Expectations and the recovery process. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:605–609, 1982Google Scholar

93. Ralph RO: Review of the Recovery Literature: A Synthesis of a Sample of Recovery Literature. Alexandria, Va, National Association for State Mental Health Program Directors, National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning, 2002Google Scholar

94. Smith MK: Recovery from a severe psychiatric disability: findings from a quantitative study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:149–158, 2000Google Scholar

95. Olincy A, Harris JG, Johnson LL, et al: Proof-of-concept trial of an alpha7 nicotinic agonist in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:630–638, 2006Google Scholar

96. Barch DM, Carter CS: Amphetamine improves cognitive function in medicated individuals with schizophrenia and in healthy volunteers. Schizophrenia Research 77:43–58, 2005Google Scholar

97. Bachmann RF, Schloesser RJ, Gould TD, et al: Mood stabilizers target cellular plasticity and resilience cascades: implication for the development of novel therapeutics. Molecular Neurobiology 32:173–202, 2005Google Scholar

98. Duman RS, Nakagawa S, Malberg J: Regulation of adult neurogenesis by antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 25:836–844, 2001Google Scholar

99. Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, et al: Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 301:805–809, 2003Google Scholar

100. Konradi C, Heckers S: Antipsychotic drugs and neuroplasticity: insights into the treatment and neurobiology of schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 50:729–742, 2001Google Scholar

101. Sassi RB, Nicoletti M, Brambilla P, et al: Increased gray matter volume in lithium-treated bipolar patients. Neuroscience Letters 329:243–245, 2002Google Scholar

102. Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, et al: Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:361–370, 2005Google Scholar

103. Kahn RS, Utrecht UM: Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia as an endophenotype. Presented at the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology Annual Meeting, Amsterdam, Oct 22–26, 2005Google Scholar

104. Meltzer HY: Cognitive factors in schizophrenia: causes, impact, and treatment. CNS Spectrums 9(10 suppl 11):15–24, 2004Google Scholar

105. Menezes NM, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB: A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis. Psychological Medicine 36:1349–1362, 2006Google Scholar

106. Robinson D, Woerner M, Alvir J, et al: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:241–247, 1999Google Scholar

107. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Case management for the severely mentally ill: a review of the research. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37–74, 1998Google Scholar

108. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, et al: Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia. I: one-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and expressed emotion. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:633–642, 1986Google Scholar

109. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, et al: Illness management and recovery: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284, 2002Google Scholar

110. Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al: Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:866–876, 2004Google Scholar

111. Herz MI, Lamberti JS, Mintz J, et al: A program for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:277–283, 2000Google Scholar

112. Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, et al: Integrated treatment ameliorates negative symptoms in first episode psychosis-results from the Danish OPUS trial. Schizophrenia Research 79:95–105, 2005Google Scholar

113. Keefe RS, Silva SG, Perkins DO, et al: The effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:201–222, 1999Google Scholar

114. Harvey PD, Keefe RS: Studies of cognitive change in patients with schizophrenia following novel antipsychotic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:176–184, 2001Google Scholar

115. Wykes T, Reeder C, Corner J, et al: The effects of neurocognitive remediation on executive processing in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:291–308, 1999Google Scholar

116. Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J, et al: The effects on the brain of a psychological treatment, cognitive remediation therapy (CRT): an fMRI study. British Journal of Psychiatry 181:144–152, 2002Google Scholar

117. Medalia A, Dorn H, Watras-Gans S: Treating problem-solving deficits on an acute care psychiatric inpatient unit. Psychiatry Research 97:79–88, 2000Google Scholar

118. Medalia A, Revheim N, Casey M: The remediation of problem-solving skills in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:259–267, 2001Google Scholar

119. Medalia A, Revheim N, Casey M: Remediation of problem-solving skill in schizophrenia: evidence of a persistent effect. Schizophrenia Research 57:165–171, 2002Google Scholar

120. McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Pascaris A: Cognitive training and supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: one-year results from a randomized controlled trial. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31:898–909, 2005Google Scholar

121. McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, et al: A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1791–1820, 2007Google Scholar

122. Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Perkins DO, et al: Implications for the neural basis of social cognition for the study of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:815–824, 2003Google Scholar

123. Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, et al: UCSD performance-based skills assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:235–245, 2001Google Scholar

124. Bellack AS, Gold JM, Buchanan RW: Cognitive rehabilitation for schizophrenia: problems, prospects, and strategies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:257–274, 1999Google Scholar

125. Bellack AS, Sayers M, Mueser K, et al: Evaluation of social problem solving in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 103:371–378, 1994Google Scholar

126. Cook JA: Blazing new trails: using evidence-based practice and stakeholder consensus to enhance psychosocial rehabilitation services in Texas. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:305–306, 2004Google Scholar

127. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Skills training versus psychosocial occupational therapy for persons with persistent schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1087–1091, 1998Google Scholar

128. Bond GR: Supported employment: evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27: 345–359, 2004Google Scholar

129. Corrigan PW, Mueser KT, Bond GR, et al: The Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. New York, Guilford, 2007Google Scholar

130. Roadmap to Recovery and Cure. Arlington, Va, NAMI Policy Research Institute, 2004Google Scholar

131. Rosenheck R, Tekell J, Peters J, et al: Does participation in psychosocial treatment augment the benefit of clozapine? Archives of General Psychiatry 55:618–625, 1998Google Scholar

132. Rog DJ: The evidence on supported housing. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:334–344, 2004Google Scholar

133. Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M: Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health 94:651–656, 2004Google Scholar

134. Bartels SB, Mueser KT, Miles KM: A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophrenia Research 27:181–190, 1997Google Scholar

135. McHugo GM, Bebout RR, Harris M, et al: A randomized controlled trial of supported housing versus continuum housing for homeless adults with severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:969–982, 2004Google Scholar

136. Crowther RE, Marshall M, Bond GR, et al: Helping people with severe mental illness to obtain work: systematic review. British Medical Journal, 322:204–208, 2001Google Scholar

137. Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR: An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, in pressGoogle Scholar

138. McGurk SR, Mueser KT: Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: a review and heuristic model. Schizophrenia Research 70:147–173, 2004Google Scholar

139. Tremblay T, Smith J, Xie H, et al: The impact of specialized benefits counseling services on Social Security Administration disability beneficiaries with psychiatric disabilities in Vermont. Psychiatric Services 57:816–821, 2006Google Scholar

140. Mowbray CT, Collins ME, Bellamy CD, et al: Supported education for adults with psychiatric disabilities: an innovation for social work and psychosocial rehabilitation practice. Social Work 50:7–20, 2005Google Scholar

141. Killackey EJ, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD: Results of the first Australian randomised controlled trial of Individual Placement and Support in first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 33: 593, 2007Google Scholar

142. Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Ventura J, et al: Advances in improving and predicting work outcome in recent-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 31:530, 2005Google Scholar

143. Bellack AS: Skills training for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:375–391, 2004Google Scholar

144. Mueser KT, Bellack AS: Social skills training: alive and well? Journal of Mental Health 16:549–552, 2007Google Scholar

145. Glynn SM, Marder SR, Liberman RP, et al: Supplementing clinic-based skills training with manual-based community support sessions: effects on social adjustment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:829–837, 2002Google Scholar

146. Tauber R, Wallace CJ, Lecomte T: Enlisting indigenous community supporters in skills training programs for persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:1428–1432, 2000Google Scholar

147. Solomon P: Peer support/peer provided services: underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:392–401, 2004Google Scholar

148. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903–910, 2001Google Scholar

149. Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC, Huntzinger C, et al: Randomized controlled trial of the use of compensatory strategies to enhance adaptive functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1317–1328, 2000Google Scholar

150. Bond GR, Resnick SG, Drake RE, et al: Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69: 489–501, 2001Google Scholar

151. Torrey WC, Mueser KT, McHugo GJ, et al: Self-esteem and vocational rehabilitation in adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:229–233, 2000Google Scholar

152. Van de Willige G, Wiersma D, Nienhuis FJ, et al: Changes in quality of life in chronic psychiatric patients: a comparison between EuroQoL (EQ-5D) and WHOQoL. Quality of Life Research 14:441–452, 2005Google Scholar

153. Farkas MD, Anthony WA: Psychiatric Rehabilitation Programs: Putting Theory Into Practice. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989Google Scholar

154. Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Roe D: Psychotherapy and recovery in schizophrenia: a proposal of key elements for an integrative psychotherapy attuned to narrative in schizophrenia. Psychological Services 4:28–37, 2007Google Scholar

155. Copeland ME: Wellness Recovery Action Plan. Dummerston, Vt, Peach Press, 1997Google Scholar

156. Deegan PE: The lived experience of using psychiatric medication in the recovery process and a shared decision-making program to support it. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 31:62–69, 2007Google Scholar

157. Kilma J, Juvakka T, Nikkonen M, et al: Hope and schizophrenia: an integrative review. Journal of psychiatric and mental health nursing 13:651–664, 2006Google Scholar