Mental Illness, Previous Suicidality, and Access to Guns in the United States

Guns were involved in over 29,500 deaths in the United States in 2004, 57% of which were attributed to suicide ( 1 ). Case-control studies indicate that individuals who commit suicide are more likely to have had access to guns ( 2 ). Regions in the United States with higher levels of gun ownership have higher suicide rates, even after accounting for regional differences in the prevalence of lifetime depression and suicidal thoughts ( 3 ).

Mental illness is a strong risk factor for suicide ( 4 ). However, in a clinical sample of older adults, those with suicidal ideation and depression were equally likely to have a gun in the home as those without psychiatric problems ( 5 ). Currently, little is known about the association between mental illness and gun access in broader, nationally representative samples.

Studies of individuals who survived suicide attempts suggest that many suicide attempts are impulsive ( 6 ). Slowing gun access may reduce impulsive but highly lethal attempts with guns. Keeping a gun locked and unloaded and storing ammunition locked in a separate location are associated with lower rates of gun suicide ( 7 ).

Most public health interventions related to gun safety have focused on reducing gun-related deaths among children. However, Oslin and colleagues ( 5 ) suggest that similar strategies could improve gun safety among individuals with mental disorders. A better understanding of gun storage practices among individuals with mental disorders could potentially lead to targeted interventions in this area.

This study examined associations between mental disorders, previous suicidality, and gun access and gun storage practices in a nationally representative sample.

Methods

The National Comorbidity Survey: Replication (NCS-R) is a psychiatric epidemiologic survey conducted during 2001–2003 using a multistage clustered area probability sample of the English-speaking U.S. household population aged 18 years and older ( 8 ). The NCS-R consisted of two parts. Part I included a core diagnostic assessment of DSM-IV mental disorders (N=9,282). Part II was administered to a probability sample (N=5,692) of Part I respondents and oversampled individuals with clinically significant psychopathology as determined by the Part I assessment. The sample weights provided in the public release of the NCS-R data set adjust for differential probabilities of selection, oversampling of Part I respondents with a mental disorder, and nonresponse while also post-stratifying the sample to the 2000 Census on sociodemographic and geographic variables ( 8 ). The institutional review board at the University of Michigan approved this secondary analysis of the NCS-R data.

Lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses of all mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders were identified by using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 3.0. We calculated a composite variable reflecting one or more of these disorders.

Related to lifetime suicidality, participants were asked, "Have you ever seriously thought about committing suicide?" "Have you ever made a plan for committing suicide?" and "Have you ever attempted suicide?" Because of the sensitivity of the topic, respondents able to read were queried on these items in a written booklet presented by the interviewer, whereas all others were asked directly.

Participants were also asked, "How many guns that are in working condition do you have in your house, including handguns, rifles, and shotguns?" and "Not counting times you were hunting or shooting targets, how many days during the past 30 days did you carry a gun outside your home?" We recoded these items into 0 versus 1 or more. Participants who reported access to a gun were asked, "Are any of these guns currently loaded and unlocked?"

For each suicide and mental disorder indicator, we estimated the prevalence of gun behaviors among those endorsing the item. Additionally, we conducted separate logistic regression analyses for each predictor-gun behavior pair (that is, each suicide variable and gun access, each suicide variable and gun carrying, each suicide variable and gun storage, each mental disorder variable and gun access, each mental disorder variable and gun carrying, and each mental disorder variable and gun storage). We used the Taylor expansion method to estimate sampling errors of estimators based on complex sample designs with the SURVEYLOGISTIC and SURVEYFREQ procedures in SAS 9.1.

We calculated the power to detect a difference between groups of 5% for each predictor-gun behavior pair. Power to detect differences between the variable any lifetime disorder and outcome variables was high, ranging from .97 (psychiatric disorder and gun access) to 1.00 (psychiatric disorder and gun carrying).

Power to detect differences was <.8 for 23 of the 30 predictor-gun behavior pairs. The power was <.8 for associations between gun access and bipolar disorder, dysthymia, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicide plan, and suicide attempt and for associations between bipolar disorder and gun carrying and risky gun storage.

Results

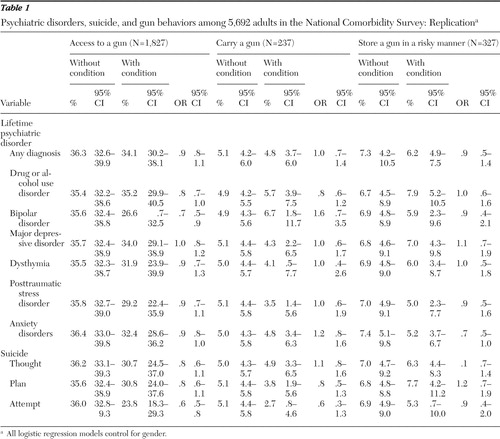

Overall, 35.4% (N=1,827) of the participants in the NCS-R had one or more guns in working condition in the home, 5.0% (N=237) had carried a gun outside the home in the past 30 days, and 6.9% (N=327) had a gun stored unlocked and loaded. As shown in Table 1 , individuals with a history of a mental disorder were as likely as persons without such a history to have access to guns (34.1% versus 36.3%; odds ratio [OR]=.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.8–1.1). Of the mental disorders examined, only bipolar disorder was significantly associated with gun access, and it was associated with lower rates of gun access. Past suicide attempts were associated with a lower likelihood of gun access, but suicidal thoughts and plans were unrelated to access.

|

Participants with a lifetime psychiatric disorder and those with past suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts were as likely as those without to either carry a gun or store a gun in a potentially unsafe manner (unlocked and loaded).

Discussion

Despite being at an elevated risk of suicide ( 4 ), community residents with mental illnesses are as likely to have access to guns as individuals without these disorders. This finding is consistent with prior research in clinical samples ( 5 ).

Given that a recent review of suicide prevention strategies reported that restriction of access to lethal means was one of only two interventions with reasonable empirical support ( 9 ), clinicians should consider screening high-risk individuals for gun access and encourage these individuals to discuss methods for delaying access to guns or preventing access during high-risk periods.

Also, our finding that individuals with mental disorders were no more or less likely to have access to guns than others suggests that the previously established link between guns and suicide is unlikely to be solely explained by higher levels of gun access among at-risk individuals ( 3 ). Instead, at-risk individuals may simply be more likely to use the guns that they possess to harm themselves.

A potentially encouraging finding is that individuals with past suicide attempts are already less likely to have access to a gun. State laws designed to limit access to guns among individuals with severe mental illness may partially explain lower rates of access among those with past suicide attempts and those with bipolar disorder ( 10 ). Alternatively, individuals who have made past suicide attempts with guns may no longer have been alive to participate in the NCS-R. This latter interpretation is consistent with the finding that suicidal ideation was not associated with a lower likelihood of having access to a gun.

There are several caveats to consider when interpreting these results. First, we examined the relationship between gun access and a subset of mental disorders. Because of NCS-R limitations we were unable to examine the relationship between psychotic disorders and gun access and safety practices. Second, the validity of the gun-related items and their relationship to actual gun access and behaviors are unknown. The NCS-R was designed to provide estimates of prevalence of psychopathology in the United States ( 8 ). Despite the sample's large size, low numbers of participants with certain conditions diminished our power to test the relationship between specific mental disorders and gun access and safety practices. Finally, the cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for determination of causality.

Conclusions

This study was the first to examine the relationship between mental health, gun access, and gun storage practices in the United States. Individuals with mental disorders were as likely to have access to guns as individuals without mental disorders, although those with past suicide attempts were less likely to have access to a gun. Given the previously established relationship between mental health risk factors and suicide ( 4 ), clinicians may want to routinely discuss gun access and storage with their patients with psychiatric problems.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by grants MRP-05-137 and IIR-04-104-2 from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development Service and by grant R01-MH-078698-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the VA or NIMH. The authors thank the members of the National Comorbidity Survey: Replication (NCS-R) research group for allowing other researchers to access their data. A complete list of other NCS-R publications and the measures used in the NCS-R are available at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. The manuscript was not reviewed or endorsed by the NCS-R research group and does not necessarily represent the opinions of its members.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System: Leading Causes of Death Reports. Atlanta, Ga, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007Google Scholar

2. Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Somes G, et al: Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. New England Journal of Medicine 327:467–472, 1992Google Scholar

3. Miller M, Lippmann S, Azrael D, et al: Household firearm ownership and rates of suicide across the 50 United States. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection and Critical Care 62:1029–1035, 2007Google Scholar

4. Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, et al: Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: revisiting the evidence. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 25:147–155, 2004Google Scholar

5. Oslin DW, Zubritsky C, Brown G, et al: Managing suicide risk in late life: access to firearms as a public health risk. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 12:30–36, 2004Google Scholar

6. Simon TR, Swann AC, Powell KE, et al: Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 32:49–59, 2001Google Scholar

7. Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al: Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA 293:707–714, 2005Google Scholar

8. Kessler RC, Berglund P: The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:69–92, 2004Google Scholar

9. Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al: Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 294:2064–2074, 2005Google Scholar

10. Norris DM, Price M, Gutheil T, et al: Firearm laws, patients, and the roles of psychiatrists. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1392–1396, 2006Google Scholar