The Effect of the Quality of Sibling Relationships on the Life Satisfaction of Adults With Schizophrenia

There has been a growing recognition of the importance of social relationships to the quality of life of persons with schizophrenia ( 1 , 2 ). Consistent with the literature on social support, adults with schizophrenia report higher life satisfaction when they have close friendships ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). However, little is known about the contribution of close relationships with siblings—who, like friends, are age peers—to the quality of life of persons with schizophrenia.

Sibling relationships may be particularly important because few adults with schizophrenia marry and have children. As parents grow older and ultimately die, many adults with mental illness may turn to their siblings for help in time of need. Siblings also expect to support their sibling with mental illness when their parents are no longer able to assume this role ( 5 ). Having a close and mutually supportive relationship with an adult sibling may have a special meaning to individuals with schizophrenia because of their lifelong bond and shared family history. Thus the sibling relationship has the potential to be one of the most significant relationships for adults with schizophrenia. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that adults with schizophrenia would report greater life satisfaction when they had a closer relationship to their sibling.

Methods

The data come from the third wave (2003–2004) of a longitudinal survey of aging families of adults with schizophrenia when the sibling substudy was added to the research protocol. Families were recruited through community support programs, the local media, and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Mothers aged 55 and older were the primary respondents and were asked to participate if they provided at least weekly assistance with a major activity of daily living to their sons or daughters with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. With the mother's consent, the son or daughter was asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire. Also, mothers were asked to identify which of their other adult children would be most involved in the future care of the adult with schizophrenia. This sibling was contacted and asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and informed consent was obtained.

Of the 160 adults with schizophrenia who participated in the third wave of the study, 94 had a sibling who participated. One of the dyads was dropped from the analysis because of missing data on key study variables. Thus data were analyzed for 93 dyads of adults with schizophrenia and their siblings. The mean±SD age of adults with schizophrenia was 43.7±8.7 years, and 27 (29%) were female. Siblings' mean age was 45.1±9.1 years, and 53 (56%) were female. Only five (5%) sibling dyads were from a racial or ethnic minority group: four (4%) were African American and one (1%) was nonwhite Hispanic. Although mothers who participated in the larger study were recruited through NAMI, only 11% of the sibling participants (N=11) were either present or past members of NAMI.

Life satisfaction, the dependent variable, was measured by the self and present life subscale of the Satisfaction With Life Scale ( 6 ). This subscale consists of six items asking the adult with schizophrenia to rate his or her satisfaction with different aspects of their psychological well-being along a 5-point scale (0, not at all, to 4, a great deal). Possible scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction. The reliability and validity of the scale has been established ( 6 ), and the scale has been widely used in studying the life satisfaction of persons with schizophrenia ( 7 ). The Cronbach's alpha of reliability was .88.

With respect to independent variables, the quality of the sibling relationship was measured by the Positive Affect Index (PAI) ( 8 ) and completed by the sibling. The PAI defines a close relationship as one that is characterized by mutual feelings of respect, understanding, trust, affection, and fairness. Five questions address the sibling's expression of these five positive sentiments toward his or her sibling with schizophrenia, and five questions represent the sibling's perception that these five positive sentiments are reciprocated by his or her brother or sister with schizophrenia. Each item is rated on a 6-point scale (1, not at all, to 6, extremely) and summed for a total score. Possible scores range from 10 to 60, with higher scores indicating better quality of relationships. The Cronbach's alpha reliability was .92. The PAI has been widely used in studies investigating relationship quality among family members in adulthood ( 8 ).

On the basis of past research ( 2 , 3 , 4 , 9 ) the following control variables were included in the analysis: whether the adult with schizophrenia had a confidant outside the family, severity of psychiatric symptoms, and the age and gender of the adult with schizophrenia. Whether the adult had a confidant outside the family was based on the response to the following question: "Is there a friend outside your family with whom you can really share your private feelings or concerns?" (1, yes, and 0, no). Psychiatric symptoms were measured by the total score on the Brief Symptom Inventory ( 10 ). Age was coded in years, and gender was coded as 0, female, and 1, male.

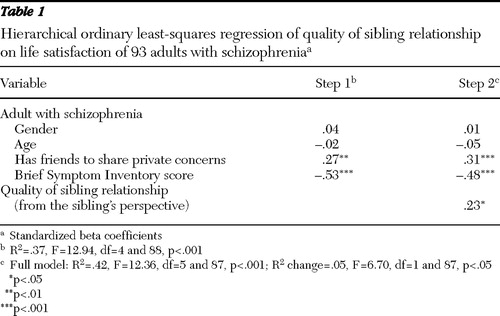

The data were analyzed by using hierarchical linear regression, with the control variables entered on the first step and the quality of the sibling relationship entered on the second step.

Results

As shown in Table 1 , in step 1 the control variables explained 37% of the variance in the life satisfaction of the participants with schizophrenia. Those who reported having a confidant were more likely to report higher life satisfaction, but individuals who were more symptomatic were less satisfied. Age and gender were not related to life satisfaction. Entering the quality of the sibling relationship on the second step explained an additional 5% of the variance. Adults with schizophrenia reported higher levels of life satisfaction when their siblings reported that their relationships were close and mutually supportive.

|

Discussion

Our findings speak to the importance of the sibling relationship to the quality of life of individuals with schizophrenia. Even after the analysis controlled for having a confidant and the severity of symptoms, adults with schizophrenia reported significantly higher levels of life satisfaction when they had a close relationship with their sibling. In addition, the association between quality of the sibling relationship and life satisfaction was quite robust, because the adults with schizophrenia reported their life satisfaction and their sibling independently rated the quality of their relationship.

These findings provide further evidence of the saliency of the sibling relationship to the well-being of adults with schizophrenia. In this study, it was related to the life satisfaction of adults with schizophrenia. We previously found that the quality of the relationship affected the sibling's willingness to take on a future caregiving role ( 11 ). Programs and interventions need to be developed to support and sustain the involvement of siblings in the lives of their brothers and sisters with schizophrenia. Mental health providers may need to personally reach out to siblings to encourage their participation in support and education groups, or they may need to work with NAMI in adapting the Family-to-Family education program to meet the unique needs of siblings ( 5 , 12 ). Because many siblings will take on a more active caregiving role in the future, the further development of workshops to help siblings plan for the future is warranted ( 5 ).

In our study a close relationship was one characterized by a high degree of reciprocity between siblings in expressions of trust, understanding, affection, fairness, and respect. Although there are several unique characteristics of the sibling bond with respect to the duration of the relationship and a shared family history, we would expect that a similar type of close relationship with a non-family member would have equivalent effects on the quality of life of persons with schizophrenia. We focused here on the sibling relationship because, for the most part, past research has emphasized the role of friendships and neglected the importance of close sibling relationships to the quality of life of persons with schizophrenia.

To gain a greater understanding of what siblings might do to enhance the relationship with their brother or sister with schizophrenia, we conducted an exploratory post hoc analysis of the association between the quality of the sibling relationship and activities that the sibling reported doing with his or her brother or sister with schizophrenia. Siblings were asked about how often (0, never, to 7, daily) they initiated one of four social activities that brothers and sisters typically share in adulthood (for example, going out to eat, to a movie, bowling, or to another recreational activity). Also, sibling participants were asked about the amount of caregiving assistance (0, not at all, to 3, a lot) they provided with six activities of daily living (for example, help with household chores). A majority of the siblings (59 siblings, or 63%) reported initiating one or more social activities at least a few times a year. Not surprisingly, these siblings had significantly higher quality of relationships than siblings who did not share or rarely did social activities together (mean±SD PAI score of 45.5±7.6 compared with a mean score of 38.6±8.9; t=4.04, df=1, p<.001). The quality of the relationship was not related to the amount of caregiving assistance that the sibling provided to his or her brother or sister with schizophrenia. This exploratory analysis suggests that strong sibling bonds are sustained when siblings initiate contact that provides opportunities to step outside the caregiving role and enjoy one another's companionship in activities typically shared by adult siblings in the general population.

There are two important limitations to the study. First, the sibling participant was nominated by the mother as the one most likely to be involved in the future care of the adult with schizophrenia. Future research is needed to determine whether our findings are generalizable to the relationships with other siblings in the family. Second, the data are cross sectional. It is possible that when adults with schizophrenia are more satisfied with their lives, they have a greater capacity for intimacy and thus are able to develop or maintain more positive relationships with others.

Conclusions

Research has clearly documented the many challenges siblings face when a brother or sister develops a mental illness. By focusing, as we do here, on the sibling relationship as a resource to individuals with mental illness, we do not intend to minimize the very real burdens that many siblings experience. Yet giving voice to the positive role of sibling relationships may lessen the burden by helping siblings recognize that their involvement matters and is pivotal to the recovery of persons with mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Support for the preparation of this brief report was provided by grants R01-MH-55928 (principal investigator, Jan S. Greenberg, Ph.D.) and T32-MH-065185 (principal investigator, Linda M. Cottler, Ph.D.) from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and by grant P30-MH-068579 from NIMH through the Center for Mental Health Services Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Angell B, Test MA: Contexts of social relationship development among assertive community treatment clients. Mental Health Services Research 5:13–25, 2005Google Scholar

2. Baker F, Jodrey D, Intagliata J: Social support and quality of life of community support's clients. Community Mental Health Journal 28:397–411, 1992Google Scholar

3. Caron J, Tempier R, Mercier C, et al: Components of social support and quality of life in severely mentally ill, low income individuals, and a general population group. Community Mental Health Journal 34:459–475, 1998Google Scholar

4. Hansson L, Middelboe T, Merinder L, et al: Predictors of subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients living in the community: a Nordic multicentre study. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 45:247–258, 1999Google Scholar

5. Hatfield A, Lefley HP: Future involvement of siblings in the lives of persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 41:327–338, 2005Google Scholar

6. Test MA, Greenberg JS, Long JD, et al: Construct validity of a measure of subjective satisfaction with life of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 56:292–300, 2005Google Scholar

7. Brekke JS, Kohrt B, Green MF: Neuropsychological functioning as a moderator of the relationship between psychosocial functioning and the subjective experience of self and life in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:697–708, 2001Google Scholar

8. Bengtson VL: Positive Affect Index: subjective solidarity between parents and children, in Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques. Edited by Touliatos J, Perlmutter BF, Strauss MA. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1990Google Scholar

9. Merciere C, Peladeau N, Tempier R: Age, gender, and quality of life. Community Mental Health Journal 34:487–500, 1998Google Scholar

10. Derogatis LR: The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual, 2nd ed. Minneapolis, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1992Google Scholar

11. Smith MJ, Greenberg JS, Mailick Seltzer M: Siblings of adults with schizophrenia: expectations about future caregiving roles. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 77:29–37, 2007Google Scholar

12. Lukens EP, Thorning H, Lohrer S: Sibling perspective on severe mental illness: reflections on self and family. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 74:489–501, 2004Google Scholar