U.S. Cambodian Refugees' Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Mental Health Problems

Each year approximately 72 million U.S. adults, more than a third of the adult population, use some form of complementary and alternative medicine ( 1 ). Complementary and alternative medicine is typically defined as health care practices or interventions that are generally found outside of the formal conventional health care system ( 2 ). Recent research indicates that individuals rely on complementary and alternative medicine not only for treatment of physical health problems but also for treatment of psychiatric problems ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). Moreover, these studies indicate that individuals may turn to complementary and alternative medicine more often than Western conventional medical or mental health services to treat their psychiatric problems ( 2 , 4 ).

Researchers have posited that Asian Americans may be particularly disposed toward using complementary and alternative medicine for mental health problems ( 6 , 7 , 8 ). Some have suggested that within traditional Asian cultures, mental illness may be commonly viewed as the result of underlying physical problems, metaphysical imbalances, or offenses committed against spirits or deities ( 9 , 10 ). To the extent that Asian Americans, particularly immigrants and refugees, hold these views, they may be more likely to seek mental health care from complementary and alternative medicine providers ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ).

In addition, some have suggested that use of complementary and alternative medicine services may inhibit the use of Western mental health services among Asian Americans ( 16 , 17 , 18 ). For example, the U.S. Surgeon General's report Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity concluded that reliance on alternative resources is a contributing factor to underutilization of Western mental health services among Asian Americans ( 17 ). Yet little empirical research has examined the prevalence of use of complementary and alternative medicine for psychiatric disorders by Asian Americans ( 18 ). Existing knowledge of the prevalence of Asian Americans' use of complementary and alternative medicine services for psychiatric problems is based primarily on anecdote, expert opinion, and small qualitative studies ( 6 , 8 , 9 , 19 , 20 , 21 ). Quantitative research directly addressing these questions is relatively rare, owing to the fact that these questions are best addressed in samples with large numbers of individuals in need of treatment, and few studies exist that contain substantial samples of Asian Americans with mental illness.

In two of the most rigorously conducted studies with large Asian-American community samples, comparable or greater rates of Western mental health service utilization were documented compared with those of complementary and alternative medicine utilization ( 22 , 23 ). However, the degree of mental health need among these service seekers was not clearly established. Hence, patterns of complementary and alternative medicine and Western conventional psychiatric care among Asian Americans with documented mental health need are relatively unknown.

For the study presented here, we examined these issues using a probability sample of the largest Cambodian refugee community in the United States ( 24 ). Questions about mental health service use are highly relevant to Cambodian refugees, inasmuch as this community continues to experience high rates of mental health problems ( 24 ). In addition, several researchers have emphasized the importance of complementary and alternative medicine services among Southeast Asian refugees ( 25 , 26 ).

The purposes of this study were threefold. First, we examined the rates at which Cambodian refugees with mental health need sought help from complementary and alternative medicine and Western sources of care for assistance with their psychiatric problems. Second, we evaluated the extent to which complementary and alternative medicine was used in the absence of Western mental health treatment. Finally, we assessed whether use of complementary and alternative medicine was associated with lower use of conventional Western mental health care.

Methods

Sample design and participants

Our sample was designed to represent the population of Cambodian immigrants residing in Long Beach, California, home to the largest single concentration of Cambodian refugees in the United States. Specifically, we derived our sample from a geographically contiguous area composed of the four census tracts with the largest proportion of Cambodians in Long Beach, containing approximately 15,000 households. We used a three-stage random sample of individuals within households within blocks. In the first stage, a simple random sample of census blocks was selected. A community expert then classified all 5,555 households on selected blocks as either likely (18%) or unlikely (82%) to be Cambodian households, by relying on signs visible from the street, including plants favored by the community and Buddhist icons. In the second stage, we used the likely and unlikely classifications to create sampling strata so that we could then draw random samples of households from within each of these strata.

Selected households (N=2,059) were then screened to determine whether they contained at least one eligible individual between 35 and 75 years of age who had lived in Cambodia during some portion of the Khmer Rouge regime (April 1975 to January 1979) and spoke Khmer. Screening was successfully completed for 2001 (97%) of the sampled households. A total of 586 households (29%) contained 719 eligible Cambodians. In the third stage, a single eligible individual was selected at random from each household. Of selected individuals, 527 (90%) agreed to participate in the survey, resulting in an overall response rate of 87%. Thirty-seven individuals who came to the United States as immigrants, rather than as refugees, were excluded from analyses, resulting in an analytic sample of 490. A more detailed description of the sampling design is provided elsewhere ( 24 ).

The analyses in the study presented here are restricted to the 339 participants (69%) who met diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression, or alcohol use disorder. Thus the analyses are based entirely on a sample that has a demonstrated need for services. Diagnoses of PTSD and major depression in the past 12 months were assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 2.1 ( 27 ). The CIDI was designed for lay administration and is keyed to the DSM-IV criteria ( 28 ). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test ( 29 ), developed as part of an international World Health Organization collaborative project, was used to screen for alcohol use disorders. Additional information on these instruments can be found elsewhere ( 24 ).

Interviewers and procedures

The interview team comprised five bilingual lay interviewers. Interviewers were themselves Cambodian refugees and could read, write, and speak fluently in both Khmer and English. Interviewers received extensive training before conducting interviews and were actively supervised throughout data collection. Data were obtained via face-to-face, fully structured interviews that took place in participants' homes between October 2003 and February 2005. Interviews were conducted in Khmer and took approximately two hours to complete. After the interview, participants received a nominal financial incentive of $25. The institutional review board of RAND approved the protocol and monitored the study. Written informed consent was obtained.

Measures

Instruments were translated and back-translated following recommended procedures ( 30 ). Two Cambodians translated all English measures into Khmer. The Khmer version of the survey was then back-translated into English by a third Khmer translator to ensure equivalency and identify discrepancies between the two English versions. Discrepancies were reconciled with the aid of the three original translators and one additional translator who had not been involved in either of the initial translations. Extensive development work preceded finalization of the instrument, the details of which are presented elsewhere ( 24 ).

Sociodemographic variables. The survey instrument assessed participants' age, gender, marital status, education, employment, health insurance status, self-assessed English-speaking proficiency, household income, and whether they were currently receiving government assistance. For analytic purposes, household income was expressed as a proportion of the federal poverty level.

Seeking services from Western care providers. Participants were asked whether they had visited "a mental health professional such as a psychologist, counselor or social worker for emotional and psychological problems in the past 12 months." They were also asked if they had visited "a Western medical care provider such as a family or primary care doctor for emotional and psychological problems in the past 12 months." Respondents were coded as having sought services from a Western care provider if they positively endorsed either question.

Seeking services from complementary and alternative medicine providers. Participants were asked whether they had visited a Kruu Khmer (that is, a traditional Cambodian healer who uses a variety of methods such as herbal medicine, massage, and other practices to treat emotional and physical disorders), a traditional Asian doctor (for example, an herbalist or acupuncturist), a monk or other religious person, or a fortune teller for emotional and psychological problems in the past 12 months. The list of complementary and alternative medicine providers used in this study was developed with input from Cambodian community advisors who lived in the study area and were familiar with the range of local complementary and alternative medicine providers. Respondents were coded as having sought services from a complementary and alternative medicine provider if they positively endorsed any question.

Trauma exposure. To assess premigration trauma exposure, respondents were asked whether they had experienced each of 35 traumatic events before immigrating to the United States. Items were drawn from a modified version of the 17-item Cambodian Harvard Trauma Questionnaire ( 31 ). Additional trauma items were taken from the 46-item Bosnian version of the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire ( 32 ). The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire is the most widely used measure of its kind and has been translated into 35 languages ( 33 ). To assess exposure to violence in the United States, a modified version of the Survey of Exposure to Community Violence was used ( 34 ). Numerous studies document the reliability and validity of this instrument ( 35 , 36 , 37 ). Respondents indicated whether they had witnessed or directly experienced each of 11 events since arriving in the United States. Separate indexes were created as proportions of total possible exposures to pre- and postmigration trauma.

Statistical analysis

Analyses used design weights and corrected for the design effects of both weighting and clustering of households within blocks. The proportion of respondents seeking contact with conventional Western and complementary and alternative medicine service providers were computed overall and separately for the type of Western and complementary and alternative medicine provider. We assessed the association between seeking complementary and alternative medicine and seeking Western mental health services in two ways. The bivariate association was assessed by using a simple chi square test of independence, with effects presented as a percentage of respondents who sought Western services among those who also sought complementary and alternative medicine services and among those who did not seek complementary and alternative medicine services.

We also looked at the association while controlling for a wide range of covariates that might be expected to influence service seeking: age, gender, marital status, English-speaking proficiency, years of overseas education, receipt of a high school education, employment status, current government assistance, household income, health insurance status, year of immigration, extent of premigration trauma, and extent of postmigration trauma. The multivariate association was assessed by using logistic regression to predict use of Western medicine and use of complementary and alternative medicine, while controlling for a variety of covariates.

We present the results of this logistic regression in the form of the covariate-adjusted proportion of respondents predicted to seek Western services first if all covariates were unchanged but all respondents used some complementary and alternative medicine and second if all covariates were unchanged but no respondents used any complementary and alternative medicine. This approach, sometimes called the method of "recycled predictions" ( 38 ), translates the adjusted odds ratios from a logistic regression into covariate-adjusted percentages that are directly comparable to the bivariate percentages. Confidence intervals for these estimates were based on the delta method ( 39 ). The data were analyzed by using SAS statistical software version 9.1.

Results

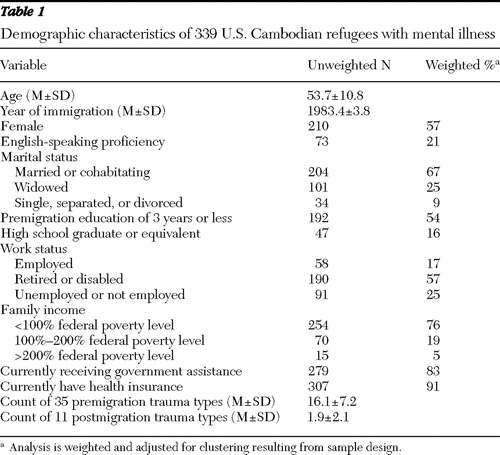

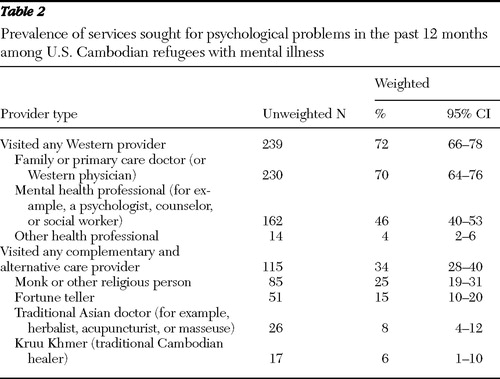

Sample characteristics for all persons with mental illness are shown in Table 1 . The participants had a mean±SD age of 53.7±10.8 years and immigrated to the United States on average in 1983 (±3.8 years). More than half were female and married, with limited formal education and English proficiency. A majority were living in poverty. Seventy-two percent had sought services from at least one type of Western service provider in the prior year for a psychological problem ( Table 2 ); 70% had visited a family or primary care doctor, 46% had visited a mental health professional, and 4% had visited another Western health professional. Roughly one-third (34%) had sought services from a complementary and alternative medicine provider, including 25% who reported visiting a monk or other religious person, 15% who saw a fortune teller, 8% who sought the services of a traditional Asian doctor, and 6% who visited a Kruu Khmer.

|

|

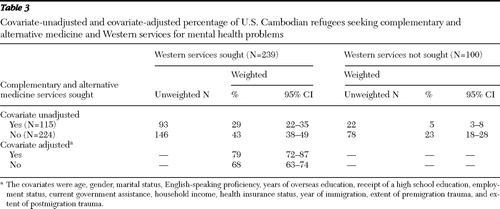

Seeking complementary and alternative medicine services for a psychological problem was strongly and positively associated with seeking Western services ( Table 3 ). Of those who sought complementary and alternative medicine services (N=115), 84% also sought Western services, whereas of those who did not seek complementary and alternative medicine (N=224), 66% sought Western services ( χ2 =13.95, df=1, p<.001) (data not shown). Moreover, only 5% (N=22) of the sample had sought care from a complementary and alternative medicine provider without having sought Western services. These findings run counter to the hypothesis that use of complementary and alternative medicine services inhibits the seeking of Western mental health treatment, although it is possible that the positive association is driven by third factors that increase overall utilization.

|

To investigate whether this association was attributable to demographic, social, or trauma variables that might create a spurious bivariate association, we also assessed the association in a multivariate model. Most of the bivariate effect remained even when the analysis controlled for a wide range of demographic and social variables thought to be predictive of service use. Specifically, this multivariate model predicted that 79% of those who sought complementary and alternative medicine would also seek Western care, whereas only 68% of those who did not seek complementary and alternative medicine services would seek Western care (t=2.39, df=1, p<.05).

Discussion

This research studied Cambodian refugees who met criteria for probable PTSD, major depression, or alcohol use disorder who were drawn from a larger probability sample of Cambodian refugees residing in the largest such community in the United States. The purposes of the study were to examine rates of mental health utilization from complementary and alternative medicine and Western conventional sources of care, to evaluate the extent to which complementary and alternative medicine care was used in the absence of Western mental health treatment, and to assess whether complementary and alternative medicine use was associated with lower use of Western mental health care.

With respect to rates of service use for mental health problems, 72% of the sample had sought psychiatric care from a conventional Western provider in the past 12 months, whereas 34% had sought psychiatric care from complementary and alternative medicine providers. Thus utilization rates in the past 12 months seem moderately high to very high for both classes of providers. The finding that Western providers were more widely used than complementary and alternative medicine providers is consistent with a previous study indicating that Asian Americans—specifically Filipino Americans—utilize Western care for mental health problems more than complementary and alternative medicine ( 22 ). In the study presented here, even though Cambodian refugees had resided in the United States for a significant duration of time (on average more than two decades), a substantial proportion relied on both Western conventional and alternative medicine for mental health problems. However, very few individuals (5%) sought complementary and alternative medicine for mental health problems without also seeking Western mental health treatment. The small size of this group implies that complementary and alternative medicine does not pose a clinically significant barrier to Western psychiatric care, even if it may inhibit a minority of individuals from seeking Western care.

With respect to the third issue, the data do not support concerns that complementary and alternative medicine use by Asian Americans, specifically Cambodian refugees, inhibits seeking services from Western mental health providers ( 17 ). Seeking care from complementary and alternative medicine providers and from Western providers was strongly and positively associated. This positive relationship was maintained even when the analysis controlled for 13 covariates (for example, extent of trauma history, age, gender, and having insurance) that could contribute to a spurious positive association. In short, seeking care from complementary and alternative medicine providers was associated with increased, rather than decreased, utilization of conventional Western sources of care.

Finally, rather than supporting the Surgeon General's concern that complementary and alternative medicine use is a barrier to conventional Western treatments ( 17 ), our data are consistent with theories suggesting that use of different types of services may actually facilitate one another. For example, both dissonance theory ( 40 ) and self-perception theory ( 41 ) suggest that seeking help for a mental health problem reinforces patients' beliefs that they would benefit from treatment and makes subsequent treatment more likely. Stated in terms of Andersen's ( 42 ) behavioral model of service utilization, seeking mental health services, regardless of the type of services, may increase the "predisposing" factors for subsequent treatment. The observed pattern is also consistent with data indicating that utilization of complementary and alternative medicine and Western conventional care for psychiatric problems are positively associated in the general U.S. population ( 4 , 43 ). Findings suggest that Cambodian refugees may view indigenous forms of treatment as a complementary rather than an opposing means to addressing psychiatric problems.

It is important to note that several aspects of our study that may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Specifically, the studied population of Cambodian refugees differs from other native-born or immigrant Asian-American groups in several respects. Most notably, they sought mental health care from both Western and complementary and alternative medicine providers at levels that were higher than those of other Asian-American groups ( 22 , 23 ) and samples of individuals with psychiatric disorders drawn from the general U.S. population ( 4 , 43 , 44 ).

Several factors likely account for the relatively high rates of mental health care utilization. Most obviously, Cambodian refugees have an unusually high mental health burden resulting from exposure to extreme levels of trauma ( 24 ). For example, approximately two-thirds of our sample met diagnostic criteria for multiple disorders, and they are likely to be more severely impaired than typical samples of diagnosed individuals. In addition, unlike most other populations, Cambodian refugees were well integrated into the social services network upon arrival in the United States, and most are eligible for publicly funded health care coverage because of poverty or disability. Some researchers have suggested that Cambodian refugees' receipt of Supplemental Security Income for trauma-related disability may facilitate contact with Western services ( 45 ). Moreover, the Cambodian refugees in our sample have resided in the United States for a significant duration of time, which may have contributed to greater familiarity with and access to Western mental health care. Additional research is needed to determine the extent to which our results generalize to populations with lower rates of psychiatric disability and to other Asian-American subgroups. Further research is also needed to better understand the treatment-seeking process, including whether complementary and alternative care or Western care is sought first, the degree to which utilization of one type of treatment may delay seeking another, and satisfaction with both types of services. Such research would yield greater insight into the exact nature in which these services are used in a complementary manner.

Conclusions

The Surgeon General has stated that Asian Americans' use of complementary and alternative medicine treatments may inhibit utilization of Western care for mental health problems ( 17 ). Contrary to this claim, we found that only a small percentage of Cambodian refugees with mental illness used complementary and alternative medicine services exclusively. Moreover, complementary and alternative medicine service use was positively associated with seeking Western sources of care for mental health problems. Thus complementary and alternative medicine service use does not appear to be a significant barrier to mental health treatment in this population. Further research is needed to examine the generalizability of this study's findings to other Asian-American groups. To the extent that Cambodian refugees are likely to seek assistance from multiple sources of care, it may be in the best interest of Cambodian refugees if Western conventional providers developed collaborative relations with complementary and alternative medicine service providers.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant R01-MH-059555 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grant R01-AA013818 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors thank the survey research team: Judy Perlman, M.A., Can Du, M.A., and Crystal Kollross, M.S., for their assistance with data collection. The authors also thank Chi-Ah Chun, Ph.D., for her insightful comments. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the interviewers and community advisors to the success of this research.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Tindle HA, Davis RB, Phillips RS, et al: Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997–2002. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 11:42–49, 2005Google Scholar

2. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al: Unconventional medicine in the United States: prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. New England Journal of Medicine 328:246–252, 1993Google Scholar

3. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al: Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 280:1569–1575, 1998Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Soukup J, Davis RB, et al: The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:289–294, 2001Google Scholar

5. Unützer J, Klap R, Sturm R, et al: Mental disorders and the use of alternative medicine: results from a national survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1851–1857, 2000Google Scholar

6. Chung RCY, Bemak F, Okazaki S: Counseling Americans of Southeast Asian descent: the impact of the refugee experience, in Multicultural Issues in Counseling: New Approaches to Diversity, 2nd ed. Edited by Lee CC. Alexandria, Va, American Counseling Association, 1997Google Scholar

7. Working With Asian-Americans: A Clinical Guide. Edited by Lee E. New York, Guilford, 1997Google Scholar

8. Lin KM, Cheung F: Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatric Services 50:774–780, 1999Google Scholar

9. Sue S, Morishima, JK: The Mental Health of Asian Americans. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1982Google Scholar

10. Sue DW, Sue D: Counseling the Culturally Different: Theory and Practice. New York, Wiley, 1999Google Scholar

11. Landrine H, Klonoff EA: Cultural diversity in causal attributions for illness: the role of the supernatural. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 17:181–193, 1994Google Scholar

12. Lee E, Lu F: Assessment and treatment of Asian American survivors of mass violence. Journal of Traumatic Stress 2:93–120, 1989Google Scholar

13. Moon A, Tashima N: Help Seeking Behavior and Attitudes of Southeast Asian Refugees. San Francisco, Pacific Asian Mental Health Project, 1982Google Scholar

14. Nishio K, Bilmes M: Psychotherapy with Southeast Asian American clients. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 18:342–346, 1987Google Scholar

15. Okazaki S: Treatment delay among Asian American patients with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:58–64, 2000Google Scholar

16. Ito KL, Maramba GG: Therapeutic beliefs of Asian American therapists: views from an ethnic-specific clinic. Transcultural Psychiatry 39:33–73, 2002Google Scholar

17. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

18. Fang L, Schinke SP: Complementary alternative medicine use among Chinese Americans: findings from a community mental health service population. Psychiatric Services 58:402, 2007Google Scholar

19. Lin K, Inui TS, Kleinman AM, et al: Sociocultural determinants of the help-seeking behavior of patients with mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 170:78–85, 1982Google Scholar

20. Shin JK: Help-seeking behaviors by Korean immigrants for depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 23:461–476, 2002Google Scholar

21. Uba L: Asian Americans: Personality Patterns, Identity, and Mental Health. New York, Guilford, 1994Google Scholar

22. Gong F, Gage SJL, Tacata LA: Helpseeking behavior among Filipino Americans: a cultural analysis of face and language. Journal of Community Psychology 31:469–488, 2003Google Scholar

23. Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi D, Hwang WC: Predictors of help seeking for emotional distress among Chinese Americans: family matters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 70:1186–1190, 2002Google Scholar

24. Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, et al: Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. JAMA 294:571–579, 2005Google Scholar

25. Helsel DG, Mochel M, Bauer R: Shamans in a Hmong American Community. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 10:933–938, 2004Google Scholar

26. Phan T: Investigating the use of services for Vietnamese with mental illness. Journal of Community Health 25:411–425, 2000Google Scholar

27. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), Version 2.1. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 1997Google Scholar

28. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

29. Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, et al: AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1992Google Scholar

30. Brislin RW: Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1:185–216, 1970Google Scholar

31. Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, et al: The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:111–116, 1992Google Scholar

32. Allden K, Ceric I, Kapetanovic A, et al: Harvard Trauma Manual: Bosnian-Herzegovina Version. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard Medical School, Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma, 1998Google Scholar

33. Harvard Trauma Questionnaire. Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma. Available at www.hprt-cambridge.org/layer3.asp?pageid=19Google Scholar

34. Richters JE, Saltzman W: Survey of Exposure to Community Violence: Self-Report Version. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1990Google Scholar

35. Berman SL, Kurtines WM, Silverman WK, et al: The impact of exposure to crime and violence on urban youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:329–336, 1996Google Scholar

36. Feigelman S, Howard DE, Li X, et al: Psychosocial and environmental correlates of violence perpetration among African-American urban youth. Journal of Adolescent Health 27:202–209, 2000Google Scholar

37. Scarpa A: Community violence exposure in a young adult sample: lifetime prevalence and socioemotional effects. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 16:36–53, 2001Google Scholar

38. Graubard BI, Korn EL: Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics 55:652–659, 1999Google Scholar

39. Skinner DJ: Domain means, regression and multivariate analyses, in Analysis of Complex Surveys. Edited by Skinner DJ, Holt D, Smith TMF. New York, Wiley, 1989Google Scholar

40. Festinger L: A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, Calif, Stanford University Press, 1957Google Scholar

41. Bem DJ: Self-perception: an alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychological Review 74:183–200, 1967Google Scholar

42. Andersen R: Behavior Models of Families' Use of Health Services. Research series no 15. Chicago, University of Chicago, Center for Health Administration Studies, 1968Google Scholar

43. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA 282:651–656, 1999Google Scholar

44. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

45. Daley TC: Beliefs about treatment of mental health problems among Cambodian American children and parents. Social Science and Medicine 61:2384–2395, 2005Google Scholar