Quality of Care in a Medicaid Population With Bipolar I Disorder

Bipolar disorder is a chronic, relapsing, disabling ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ), and often deadly illness ( 4 , 12 ). In addition to underdetection and misdiagnosis ( 4 , 5 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ), inappropriate pharmacotherapy ( 18 , 19 , 20 ) and inadequate monitoring of non-dopamine-blocking antimanic medications ( 21 ) have been observed in usual care. Further, deviations from quality, such as delaying or not providing non-dopamine-blocking antimanic medication, have been associated with higher health care costs among persons with bipolar disorder ( 18 ). Thus identifying patient characteristics associated with differences in the likelihood of receiving care recommended by treatment guidelines can be a useful policy tool for clinicians and service providers who wish to identify vulnerable patient populations.

With a focus on patients with bipolar I disorder, this study examined whether there is an association between how patients enter the treatment system and subsequent treatment quality. Specifically, we focused on presenting psychiatric diagnosis or service setting level of care (inpatient, partial hospitalization, and residential treatment versus standard outpatient treatment) and on whether patients subsequently received care recommended by treatment guidelines (an antimanic agent and psychotherapy) or care that is discouraged by guidelines (an antidepressant in the absence of a non-dopamine-blocking antimanic medication) ( 1 , 22 ).

Methods

This study received approval from the Harvard Medical School institutional review board. We used administrative data from a state fee-for-service Medicaid program for the fiscal years (FYs) 1994–2000. Each year, there were between 740,000 and 913,000 enrollees between ages 18 and 64. The administrative data included enrollment information and all medical, behavioral health, and pharmacy claims.

Treatment measures

We constructed two sets of treatment measures informed by bipolar disorder guidelines. One set of measures used guidelines published during the study years (FYs 1994–2000) ( 1 , 22 , 23 ). Through year 2000, and consistent with guidelines published until 2004 ( 24 ), acute-phase and maintenance-phase pharmacotherapy guidelines for bipolar I disorder recommended that all patients receive a non-dopamine-blocking antimanic agent (lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine). However, the most recent bipolar disorder treatment guidelines now include antipsychotic medications as appropriate monotherapy for maintenance-phase treatment of bipolar disorder ( 25 ). Therefore, as a sensitivity analysis to test the relevance of our results to the most recent guideline standards, we also conducted analyses in which we altered the pharmacotherapy measures to include antipsychotic medications as antimanic medications appropriate for acute-phase and maintenance-phase treatment.

The guidelines issued during the study years and beyond consistently recommended that patients with bipolar disorder receive both appropriate antimanic pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Therefore, our primary quality measure examined the likelihood of receiving both of these treatments. Given that some treatment modalities may be under different constraints than others, we also measured whether patients received either of these components of recommended care. Last, we examined a measure of poor quality: receipt of an antidepressant without an antimanic agent.

For each measure, we created binary variables indicating whether or not there was at least one claim for the relevant service up to one year after the first observed bipolar diagnosis. We considered a patient to have received poor-quality care if there was at least one claim for an antidepressant without any claims for an antimanic agent in the same one-year period.

Determining the bipolar sample

First, we excluded enrollees with any schizophrenia diagnoses in the claims. We included individuals who had at least two claims with diagnoses of bipolar disorder on different service dates. Enrollees with only one claim indicating bipolar disorder were included if the claim was for an inpatient service or if it represented at least 50% of their outpatient mental health claims. We focused our final study sample on persons diagnosed as having bipolar I ( ICD-9 codes 296.0–296.1 and 296.4–296.7) at some point during the study period because subtler bipolar disorder presentations may be diagnosed less accurately in claims data and because the guidelines are less clear regarding whether all persons with bipolar spectrum disorders should receive antimanic medications. The potential bipolar I study sample included 12,575 patients between ages 18 and 64. We excluded enrollees who received Medicare, because claims paid by Medicare are not observable in these data.

We considered only individuals for whom we could observe at least six months of continuous claims data before finding the first bipolar diagnosis (N=3,200). Further, because we viewed bipolar diagnoses made by mental health specialists as more likely to be accurate and because psychiatrists are more likely to prescribe antimanic medications than physicians who are not mental health specialists ( 14 ), we limited our study sample to the 2,644 persons who received at least one bipolar diagnosis by a psychiatrist.

Main explanatory variables

We examined whether presenting service level of care (that is, outpatient versus inpatient, partial hospitalization, or residential treatment) or specific presenting psychiatric diagnoses were associated with subsequent bipolar disorder treatment. These variables were defined on the basis of mental health claims in the six-month period before and including the first observed bipolar diagnoses. We coded presenting level of care using a dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the first observed psychiatric service during that period occurred in an intensive setting (that is, inpatient, partial hospitalization, or residential program) and equal to 0 otherwise.

The presenting diagnosis was defined with four mutually exclusive categories and determined by the first mental health diagnosis observed in the claims. First, patients were considered to have presented with bipolar disorder if there were no other mental health diagnoses in the six months before the first bipolar diagnosis. Patients whose first observed mental health diagnosis was bipolar disorder were then further characterized according to whether that first diagnosis included manic or hypomanic symptoms. Patients with nonbipolar diagnoses in the six-month period before their first bipolar disorder were classified into two groups on the basis of the diagnosis from their first mental health visit: depressive or anxiety disorders in one group and all other mental health diagnoses in the other group.

Depression and anxiety were combined into a composite category for two reasons. First, patients with bipolar disorder often present for treatment of depression before the first bipolar diagnosis ( 17 , 26 ). Second, agitated depressions may mistakenly be diagnosed as anxiety disorders, and there is a high co-occurrence of anxiety disorders in bipolar disorder ( 27 , 28 , 29 ). Thus we were also concerned that there may be considerable difficulties in accurately distinguishing between depressive and anxiety disorders in claims data.

Statistical analysis

To assess receipt of guideline-recommended care for bipolar disorder, we examined claims for care received up to one year after the first observed bipolar diagnosis. Of the sample, 71% were enrolled for at least six months after the first observed bipolar diagnosis and 49% were enrolled for at least 12 months.

To test whether low rates of receiving guideline-concordant care were due, at least in part, to disenrollment from the Medicaid program, we compared demographic and clinical characteristics and rates of receiving guideline-recommended treatment for individuals enrolled continuously in the Medicaid program at least ten months after the first bipolar disorder diagnosis and those enrolled for a shorter period. We selected ten months as a dividing point because it allowed a liberal period in which to expect a patient to receive a particular recommended treatment.

We used logistic regression models to examine the relationship between service-level care at the first mental health visit and presenting psychiatric diagnosis and the subsequent bipolar disorder treatment, with controls for observed patient characteristics. Separate models were fit for each of the treatment characteristics examined. The main explanatory variables were a binary variable indicating whether the patient presented in an intensive treatment setting and three binary variables for the presenting diagnosis (presenting with a nonacutely manic or hypomanic bipolar disorder diagnosis was the reference category).

Control variables included age (and its square), Supplemental Security Income eligibility status, a co-occurring substance use disorder (diagnosed either before or after the first bipolar diagnosis), preexisting medical conditions, and the number of months an individual was continuously enrolled in the fee-for-service Medicaid program in the 12 months after the first observed bipolar diagnosis. Enrollee ethnicity was not included in the model because it was frequently missing in the data set (approximately 17%).

For the preexisting medical conditions, we selected specific chronic conditions that would potentially complicate bipolar treatment either by complicating medication selection or bipolar disorder treatment adherence: cardiovascular, hepatic, thyroid, inflammatory, and seizure disorders; obesity; diabetes; migraines; and conditions that can affect cognition, such as HIV-AIDS, cerebrovascular accidents, brain tumors or anoxia, and pregnancy. All preexisting conditions were coded on the basis of ICD-9 diagnoses observed in the six-month period before the first bipolar diagnosis.

We considered that a bipolar disorder diagnosis might be suspected and treated accordingly but, for reasons of either stigma or uncertainty, may not be coded as such initially in the claims. In addition, persons may have previously received a bipolar diagnosis and have had ongoing treatment, despite having no claims with the diagnosis in those six months before our first observation of a bipolar diagnosis. We accounted for these possibilities in the model by controlling for whether an antimanic prescription (dopamine blocking or not) was received in the six-month period before the first bipolar diagnosis.

It is possible that an initial presentation of mania could be associated with a shorter period of continuous enrollment (and therefore, lower likelihood of receiving guideline-recommended treatment) or with presenting in an intensive treatment setting, which could have confounded our results. Therefore, we tested whether presenting with manic symptoms was associated with presenting in an intensive treatment setting or with differences in continuous enrollment.

Results

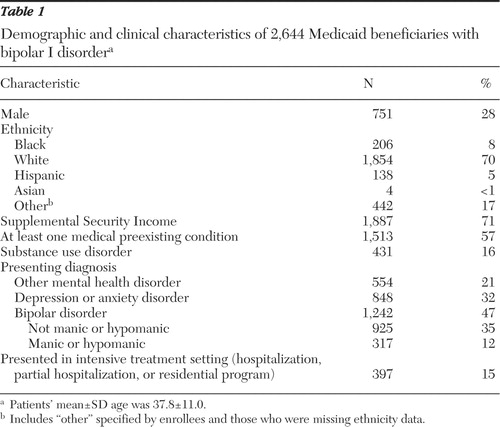

The sample was largely female, white, and enrolled in the Supplemental Security Income program ( Table 1 ). More than half also had at least one preexisting medical condition that could complicate the treatment of bipolar disorder. Of the sample, 16% were diagnosed as having a co-occurring substance use disorder. In the first observed mental health visit nearly half received a bipolar diagnosis (25% of those were diagnosed as having manic or hypomanic episodes), and 32% received a diagnosis of a depressive or anxiety disorder. Fifteen percent presented in an intensive treatment setting.

|

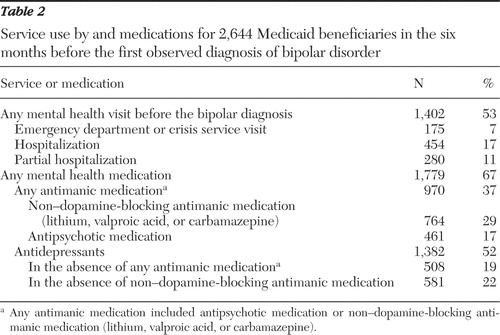

More than half presented for mental health treatment with a nonbipolar diagnosis in the six months before receiving a bipolar diagnosis ( Table 2 ). A sizeable proportion of these patients received care in an intensive setting for a nonbipolar mental health diagnosis during this period: nearly 7% in an emergency department or crisis center, 17% in a hospital, and 11% in a partial hospitalization program. Two-thirds of the patients received some type of psychiatric medication before the first bipolar diagnosis that we observed in the claims. Approximately one-third received an antimanic agent before the diagnosis. Approximately one-fifth received an antidepressant without an antimanic agent.

|

Even when the most recent pharmacotherapy recommendations in practice guidelines are considered, only approximately one-third of patients received both an antimanic medication and psychotherapy up to one year after the first observed diagnosis of bipolar disorder ( Table 3 ). Approximately half received any psychotherapy, and 67% received an antimanic medication of some type (56% received a non-dopamine-blocking antimanic medication). Nineteen percent received an antidepressant in the absence of an antimanic agent. Individuals enrolled at least ten months after the initial bipolar diagnosis were more likely to receive guideline-concordant treatment than those enrolled for shorter durations, although the proportion of those enrolled ten months or longer who received guideline-concordant care still raises concerns about quality of care. [An appendix that provides bivariate comparisons of demographic and clinical characteristics between those enrolled for at least ten months and those enrolled for shorter durations is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

|

We report adjusted differences in the likelihood of receiving each of the four quality measures according to presenting diagnosis and treatment setting, as well as according to the two guideline standards, in Table 4 . Enrollees with bipolar I disorder presenting for their first observed mental health visit in an intensive level of care were less likely subsequently to receive an antimanic medication and psychotherapy together. They were also less likely to receive the individual components of this guideline-recommended treatment combination, particularly psychotherapy. The results were similar for the regressions that used the guidelines available during the study period and the most recent guideline recommendations.

|

Diagnostic presentations were also associated with differences in quality of subsequent treatment for bipolar disorder. Again, the results were often similar regardless of which antimanic medication standard was considered (that is, whether antipsychotics were included or not). Presenting with a nonbipolar diagnosis was associated with a greater likelihood of subsequently receiving both components of recommended care.

However, when looking at the individual components of care, patients presenting with a nonbipolar diagnosis had a greater likelihood of receiving psychotherapy but a similar or lower likelihood of receiving an antimanic medication, compared with those first diagnosed as having a bipolar (nonmanic) disorder. Presenting with a nonbipolar diagnosis was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving an antidepressant in the absence of a non-dopamine-blocking antimanic medication. However, in regression models using the most recent pharmacotherapy guidelines, only presenting with depression or an anxiety disorder was associated with this poor-quality measure.

Finally, presenting with acutely manic or hypomanic symptoms (compared with bipolar but not acutely manic or hypomanic symptoms) was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving both recommended treatment components according to the contemporaneous guidelines but not the most recent guidelines. These symptoms were also associated with a lower likelihood of receiving any subsequent psychotherapy.

In examining whether presenting with manic symptoms was associated with differences in continuous enrollment or presenting in an intensive service setting, we found no significant differences in continuous enrollment but a lower probability of presenting in an intensive treatment setting if manic (4% versus 13%, p<.001). Therefore, it does not appear that an initial presentation of mania confounded our results on the likelihood of receiving guideline treatment.

Discussion

Presenting diagnosis and treatment setting were associated with differences in the likelihood of subsequently receiving guideline-concordant treatments. Most notable, diagnostic presentation had little association with subsequent antimanic medication treatment, but presenting with bipolar symptoms was associated with a lower likelihood of receiving psychotherapy and, in turn, a lower likelihood of receiving both the pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy treatments together. Further, persons first diagnosed as having a nonbipolar disorder were more likely to receive an antidepressant in the absence of an antimanic medication (a measure of poor quality) after the first observed bipolar diagnosis. Also, patients whose first treatment was in an intensive treatment setting were less likely to receive guideline-recommended treatments after receiving the first observed bipolar diagnosis.

Our results indicate quality concerns, independent of presenting diagnosis or service intensity. Allowing a more liberal definition of quality of medication treatment (that is, including the most current recommendations) showed a somewhat more optimistic picture of treatment quality. However, there were still significant shortfalls. Even among patients enrolled in the Medicaid program for at least ten months after the first observed bipolar diagnosis, only approximately 41% received guideline-recommended treatments of an antimanic medication and psychotherapy; approximately one-fifth received treatment that the guidelines advise against. Such information is an important first step in designing quality enhancement programs for persons with bipolar disorder served in the public sector. Of greater concern is the fact that these measures represent a minimum quality standard (that is, at least one therapy visit and at least one prescription for non-dopamine-blocking antimanic medication).

There are several potential limitations of our research. First, our sample was not representative of the larger bipolar I population in this Medicaid program. We excluded Medicaid enrollees who were also enrolled in the Medicare program, as well as Medicaid enrollees who were not continuously enrolled for at least six months before their first bipolar diagnosis. Our sample appeared to be a more complicated and possibly sicker group than those diagnosed as having bipolar I disorder who were not included in our sample: individuals in our sample were more likely to have a medical co-occurring condition (57% versus 22%, p<.001) and substance use disorder (16% versus 6%, p<.001) and were more likely to receive Supplemental Security Income (71% versus 43%, p<.001). Second, this study used claims data, instead of structured patient interviews and chart reviews, to identify people with bipolar I disorder; the latter may have greater accuracy in establishing a bipolar sample. However, Unützer and colleagues ( 30 , 31 ) demonstrated that claims data analyses requiring a bipolar diagnosis are valid and feasible for population-based quality assessment. Third, this study described factors associated with receiving guideline-concordant care during FYs 1994 to 2000 and may not reflect current practice patterns.

Conclusions

This study raises general concerns for quality of bipolar I disorder treatment in a medically complicated and relatively disabled sample within a Medicaid population and identified patient populations that may be particularly vulnerable to not receiving guideline-compatible care. Clinicians and service system policy makers can use such information to design treatment programs targeting such patients for additional engagement and outreach to improve treatment quality and outcomes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from grants R01-MH-61434 (Dr. Busch, Dr. Huskamp, and Dr. Landrum), K01-MH-071714 (Dr. Busch), and K01-MH-66109 (Dr. Huskamp) from the National Institute of Mental Health. Additional funding was provided for Dr. Busch by the Ralph and Marian Falk Medical Research Trust and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The funding organizations had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data. They also had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of this article. The authors thank Rita Volya, Ph.D., for her programming expertise.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 151(Dec suppl):1–36, 1994Google Scholar

2. Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, et al: Switching from "unipolar" to bipolar II: an 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:114–123, 1995Google Scholar

3. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

4. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 159(Apr suppl):1–50, 2002Google Scholar

5. Suppes T, Leverich GS, Keck PE, et al: The Stanley Foundation bipolar treatment outcome network: II. demographics and illness characteristics of the first 261 patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 67:45–59, 2001Google Scholar

6. Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Grossman LS: Course and outcome in bipolar affective disorder: a longitudinal follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:379–384, 1995Google Scholar

7. Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, et al: Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1635–1640, 1995Google Scholar

8. Coryell W, Scheftner W, Keller M, et al: The enduring psychosocial consequences of mania and depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:720–727, 1993Google Scholar

9. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:530–537, 2002Google Scholar

10. Tsai S-YM, Chen C-C, Kuo C-J, et al: 15-year outcome of treated bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 63:215–220, 2001Google Scholar

11. Strakowski SM, Tohen M, Stoll AL, et al: Comorbidity in psychosis at first hospitalization. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:752–757, 1993Google Scholar

12. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR: Manic-Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990Google Scholar

13. Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al: Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA 293:956–963, 2005Google Scholar

14. Frye MA, Calabrese JR, Reed ML, et al: Use of health care services among persons who screen positive for bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services 56:1529–1533, 2005Google Scholar

15. Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, et al: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. Journal of Affective Disorders 31:281–294, 1994Google Scholar

16. Evans DL: Bipolar disorder: diagnostic challenges and treatment considerations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:26–31, 2000Google Scholar

17. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al: Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? Journal of Affective Disorders 52:135–144, 1999Google Scholar

18. Li J, McCombs JS, Stimmel GL: Cost of treating bipolar disorder in the California Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program. Journal of Affective Disorders 71:131–139, 2002Google Scholar

19. Lim PZ, Tunis SL, Edell WS, et al: Medication prescribing patterns for patients with bipolar-I disorder in hospital settings: adherence to published practice guidelines. Bipolar Disorders 3:165–173, 2001Google Scholar

20. Blanco C, Laje G, Olfson M, et al: Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1005–1010, 2002Google Scholar

21. Marcus SC, Olfson M, Pincus HA, et al: Therapeutic drug monitoring of mood stabilizers in Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1014–1018, 1999Google Scholar

22. Sachs GS, Printz D, Kahn D, et al: Expert Consensus Guideline Series: medication treatment of bipolar disorder 2000. Postgraduate Medicine 108(Apr suppl):1–104, 2000Google Scholar

23. Bauer MS, Callahan AM, Jampala C, et al: Clinical practice guidelines for bipolar disorder from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:9–21, 1999Google Scholar

24. Keck PE Jr, Perlis RH, Otto MW, et al: Expert Consensus Series: treatment of bipolar disorder 2004. Postgraduate Medicine 116(Dec suppl):1–120, 2004Google Scholar

25. Suppes T, Dennehy EB, Hirschfeld RMA, et al: The Texas implementation of medication algorithms: update to the algorithms for treatment of bipolar I disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66:870–886, 2005Google Scholar

26. Hantouche EG, Akiskal HS, Lancrenon S, et al: Systematic clinical methodology for validating bipolar-II disorder: data in mid-stream from a French national multi-site study (EPIDEP). Journal of Affective Disorders 50:163–173, 1998Google Scholar

27. Chen YW, Dilsaver SC: Comorbidity of panic disorder in bipolar illness: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:280–282, 1995Google Scholar

28. Dittmann S, Biedermann NC, Grunze H, et al: The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network: results of the naturalistic follow-up study after 2.5 years of follow-up in the German centres. Neuropsychobiology 46 (suppl 1):2–9, 2002Google Scholar

29. Pini S, Cassano GB, Simonini E, et al: Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. Journal of Affective Disorders 42:145–153, 1997Google Scholar

30. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al: The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in a large staff-model HMO. Psychiatric Services 49:1072–1078, 1998Google Scholar

31. Unützer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al: The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:1–10, 2000Google Scholar