Understanding and Preventing Criminal Recidivism Among Adults With Psychotic Disorders

On March 5, 1998, the New York Times published a front-page headline stating "Prisons Replace Hospitals for the Nation's Mentally Ill" ( 1 ). Five years later a Human Rights Watch report noted that more people with severe mental illness reside in our prisons than in our hospitals ( 2 ). Despite concerns raised by these and similar reports ( 3 , 4 ), a consensus regarding the causes of this phenomenon is lacking. Are inmates with mental illness criminals or have they been criminalized?

This article reviews the literature on criminal recidivism among adults with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders as well as the current literature in the field of criminology. On the basis of this review and synthesis, a conceptual framework for understanding and preventing criminal recidivism is proposed and necessary elements of intervention are identified and discussed.

Scope of the problem

Psychotic symptoms are reported by 15% and 24% of all prison and jail inmates, respectively, according to the latest U.S. Department of Justice survey ( 5 ). Although these findings are based on self-report, findings about the prevalence of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders from more rigorous studies are also concerning. Using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area program, Robins and Regier ( 6 ) found that 6.7% of prisoners had experienced symptoms of schizophrenia at some point in their lives. A Correctional Service of Canada study using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule and the American Psychiatric Association's (APA's) DSM-III-R criteria found a 7.7% prevalence of psychotic disorders in a sample of 9,801 inmates ( 7 ). Also, a large study comparing the weighted prevalence of psychotic disorders between the national household survey and prisons in Great Britain found a tenfold higher prevalence of psychotic disorders among prisoners ( 8 ). These findings are consistent with reports that individuals with psychotic disorders are arrested more frequently and have higher rates of criminal conviction for both nonviolent and violent offenses, compared with the public ( 9 , 10 ).

Most persons with schizophrenia are arrested for minor crimes, such as disturbing the peace and public intoxication ( 11 ), but some commit violent acts, including assault and murder ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). Although these events are rare, their serious and tragic nature highlights the need for effective treatment strategies ( 15 ). Patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders are unlikely to receive adequate treatment within correctional facilities. According to the U.S. Department of Justice only about half of all inmates with mental illness receive treatment, with most receiving no treatment other than medications while in custody ( 16 ).

Current treatment strategies for adults with psychotic disorders

Treatment strategies for schizophrenia and related disorders have recently been evaluated in two major reviews, the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) ( 17 ) project and the APA's Practice Guideline for Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia ( 18 ). However, these reports provide little guidance about management of patients with a history of repeated arrest and incarceration. Reviewing current treatments, the PORT recommends, "Assertive community treatment programs should be targeted to individuals at high risk for repeated hospitalizations or who have been difficult to retain in active treatment with more traditional types of services." Although the PORT cites evidence that this approach is effective at reducing hospital use, it has not been shown to reduce rates of arrest and incarceration ( 19 , 20 ).

The APA's Practice Guideline for Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia reviews the literature on mandatory outpatient treatment, an intervention strategy present in 42 states ( 15 , 18 ). Mandatory outpatient treatment, also called outpatient commitment, involves the use of potential legal consequences in order to compel patients to accept outpatient treatment ( 21 ). Although not discussed by either the PORT or the APA practice guideline, legal consequences are also used in jail diversion. Jail diversion encompasses a wide range of interventions that are positioned within the criminal justice system, including mental health courts, specialized police teams, and pretrial service agencies ( 22 , 23 ). Jail diversion differs from mandatory outpatient treatment in that patients who receive the latter have typically not committed a recent crime, whereas those involved in jail diversion have been arrested or incarcerated.

For purposes of this article, the use of potential legal consequences to promote adherence to outpatient treatment will be called "legal leverage," regardless of whether the requisite legal authority originates from a judge, a probation or police officer, or another criminal justice source. Published reviews indicate that the use of legal leverage is effective at improving outpatient treatment adherence ( 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ), although findings regarding its effectiveness at reducing rates of arrest and incarceration have been mixed ( 21 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ). Examining these inconsistencies, reviews of mandatory outpatient treatment by Swartz and Swanson ( 33 ) and by Hiday ( 21 ) and reviews of jail diversion by Steadman and colleagues ( 34 ) strongly suggest that the effectiveness of legal leverage is dependent upon its use in conjunction with intensive treatment. However, a recent review of mental health courts found no standards or guidelines regarding clinical services ( 35 ). Similarly, a national survey of specialty probation programs found "staggering diversity" among agencies, including substantial variability in how they interfaced with treatment providers ( 29 ). Also, a national survey of jail diversion programs indicated that few had specific procedures to follow up with diverted detainees or to ensure that initial linkages to treatment were maintained ( 24 ). Although the APA practice guideline recommends combining mandatory outpatient treatment with "intensive individualized outpatient services," the question of how to define and deliver such services is not addressed.

In sum, our current approach to preventing criminal recidivism involves the widespread use of legal authority to promote treatment adherence in the absence of guidelines about treatment. What constitutes effective treatment for reducing arrest and incarceration among adults with psychotic disorders? Surprisingly, discussions of crime prevention within the mental health literature have largely ignored the considerable body of research on the subject within the field of criminology. A search for English-language articles in the Medline database from 1966 to 2006 with the combined keywords "schizophrenia," "crime," and "prevention" yielded only 23 articles. Less than half cited criminology journals, and none discussed how contemporary crime prevention principles could be applied to preventing criminal recidivism in schizophrenia.

Understanding criminal recidivism

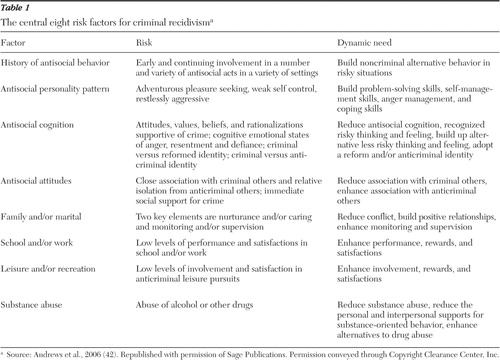

In order to develop effective prevention strategies, it is necessary to understand why adults with psychotic disorders enter the criminal justice system. Although the mental health literature typically cites deinstitutionalization and our fragmented health care system as primary causes ( 36 , 37 , 38 ), this rationale is not sufficient to explain why some patients enter the criminal justice system whereas others do not. A predominant approach to understanding and preventing arrest and incarceration in the general population includes the principles of risk, needs, and responsivity ( 39 , 40 , 41 ). This framework states that individuals with criminal recidivism have many needs, but only certain needs are associated with criminal behavior and therefore should be the target of prevention strategies. On the basis of an extensive body of research, eight primary risk factors have been established that are strongly predictive of future criminal behavior ( 41 ). These risk factors have been incorporated into standardized assessment tools that have demonstrated high levels of reliability and validity in predicting criminal recidivism ( 42 ). Table 1 shows the eight primary risk factors with their associated risks and needs.

|

Most studies of criminal recidivism have found little or no relationship between mental illness and the risk of criminal behavior ( 43 ). As noted by Andrews and colleagues ( 42 ) in their recent literature review, "the predictive validity of mental disorders most likely reflects antisocial cognition, antisocial personality pattern, and substance abuse." Adults with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders have an increased prevalence of these established risk factors. According to the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, nearly half of persons with psychotic disorders have co-occurring substance use disorders ( 44 ). Also, the prevalence of antisocial personality disorder is significantly higher among adults with schizophrenia than in the general population ( 45 ). In addition, many such individuals live in poverty and experience an associated lack of education, problems with employment, and absence of prosocial attachments ( 46 ). Adults with psychotic disorders also have high rates of homelessness, a risk factor that has been associated with criminal behavior among individuals with and those without psychotic disorders ( 47 , 48 , 49 ). The strength of homelessness as a recidivism risk factor relative to established risk factors has not been determined. However, research on the social-environmental context of violence suggests that access to appropriate housing is an essential need among adults with psychotic disorders ( 50 , 51 ).

Despite the high prevalence of established risk factors, the presence of psychosis itself may be an additional risk factor for criminal recidivism. As observed by Bonta and colleagues ( 43 ) the episodic nature of psychotic symptoms may obscure their relationship with recidivism. Such a relationship could be affected by remission of acute psychosis as well as by diversion of some patients into the mental health system. Although lack of an association between psychosis and crime was reported by the landmark MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, the study did not account for the role of social withdrawal and diminished social networks ( 52 ).

Since publication of the MacArthur study, several studies have been published that address the methodological limitations of previous studies ( 51 , 53 , 54 , 55 ). These new studies provide compelling evidence that active psychosis is an additional risk factor for violence, independent of substance use disorders or antisocial personality features. Most notably, Swanson and colleagues ( 51 ) examined the relationship between psychotic symptoms and violence by using data from 1,410 patients with schizophrenia in the rigorous Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study by the National Institute of Mental Health. The CATIE study provides a unique opportunity to examine this association because it features a large sample of patients, a highly specific measure of violent behavior, and comprehensive clinical assessments. By using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, Swanson and colleagues found that psychotic symptoms were strongly associated with increased risk of both minor and serious violence. However, violence risk was increased by positive symptoms only when negative symptoms were low, suggesting that certain levels of energy, initiative, and social contact are necessary to carry out violent acts.

Conceptual framework

The key to preventing criminal recidivism among adults with psychotic disorders is to engage them in interventions that target risk factors for recidivism. Engagement refers to the level of involvement in treatment interventions, and it encompasses both active participation in treatment as well as basic adherence to treatment ( 56 ). Adherence can be defined as "the extent to which a person's behavior coincides with medical or health advice" ( 57 ). Unfortunately, patients with psychotic disorders often refuse to accept treatment despite being advised to do so ( 58 ). Most recently, the 74% medication discontinuation rate observed in the CATIE study provides strong evidence of the need to develop strategies to improve adherence ( 59 ).

Patients are nonadherent with necessary treatment and support services for many reasons. Although the principles of risk, needs, and responsivity do not directly address treatment nonadherence, they highlight the importance of matching individuals who are at risk of arrest and incarceration with appropriate intervention strategies ( 41 ). According to the responsivity principle, an individual's likelihood of benefiting from a particular intervention is determined by internal and external responsivity factors. Internal responsivity factors are individual characteristics, including learning style, verbal intelligence, and interpersonal sensitivity. Beyond determining whether an individual is capable of responding to a given treatment approach, however, individual characteristics can affect whether an individual adheres to treatment. Studies of patients with schizophrenia have established several individual characteristics that are associated with nonadherence. These include psychotic symptoms, depression, substance abuse, attitudes toward medications, low social functioning, young age, male gender, recovery style, residential instability, and family influences ( 58 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ).

External responsivity factors are characteristics of treatment interventions or programs, such as whether a program provides outreach. Medication side effects and lack of efficacy are also known to impact adherence in schizophrenia ( 59 , 65 ). In addition, clinicians' interpersonal skills are likely to strongly affect adherence. In a recent study of medication adherence among patients with schizophrenia, quality of the relationship with clinicians was found to be an important determinant of patients' attitudes toward treatment and adherence to medications ( 66 ). Beyond clinician and program characteristics, patients may likewise fail to adhere to treatment because of geographical, financial, cultural, and language barriers.

On the basis of the risk, needs, and responsivity framework, the clinical features of adults with psychotic disorders, and the characteristics of existing service delivery systems, the following three principles are proposed regarding treatment adherence and nonadherence.

The first principle is that nonadherence is the result of a mismatch between individuals and systems of care. Rather than viewing nonadherence as a patient characteristic or label, it is conceptualized as the result of interactions between individual risk variables and service-system risk variables. Individual risk variables for nonadherence include those cited above, such as attitudes toward medications, in addition to established recidivism risk factors, such as substance abuse and lack of family caring and supervision. Service-system risk variables include an absence of necessary treatment and support services, inaccessibility of existing services because of the barriers noted above, and clinical variables, such as clinician skill level and medication side effects. Although nonadherence may still occur among low-risk patients receiving optimal services, it is more likely to occur in the presence of multiple individual and service-system risk variables.

The second principle is that nonadherence mediates the relationship between modifiable risk variables and criminal recidivism. Some established risk factors for criminal recidivism are not modifiable, such as criminal history. However, others can be modified by interventions that target the needs listed on Table 1 . Because risk factors for crime can be modified by appropriate treatment interventions, treatment nonadherence represents a common denominator in criminal recidivism. Treatment nonadherence is commonly found among both patients with schizophrenia and those with chemical dependency. It is strongly associated with homelessness, is frequently reported among offenders with mental illness, and is associated with violence and increased rates of arrest and incarceration ( 60 , 67 , 68 ). The predictive strength of nonadherence relative to established risk factors for criminal recidivism has yet to be determined. However, the fact that most central risk factors for crime are potentially treatable argues that treatment nonadherence is a critical target for crime prevention strategies.

The third principle is that adherence to standard psychiatric treatment will prevent criminal recidivism to the extent that recidivism is driven by psychiatric treatment issues. Although psychiatric treatment interventions for psychosis, co-occurring substance abuse, and homelessness can prevent criminal recidivism, these interventions are not sufficient for all patients because they do not directly address other recidivism risk factors ( 69 ). For instance, although some evidence suggests that intensive outpatient mental health services can lower recidivism rates among patients with schizophrenia and psychopathy, optimal prevention probably requires interventions that specifically target problematic personality traits ( 70 ). This principle may be especially true for individuals with antisocial behaviors that predate the onset of schizophrenia ( 71 , 72 ).

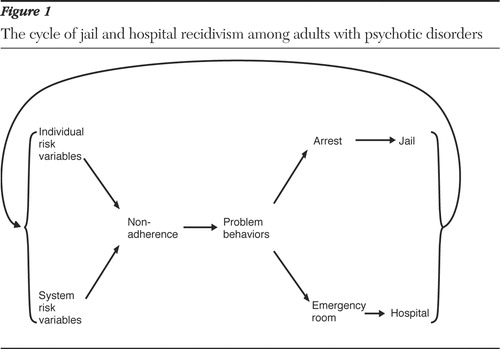

The relationship between risk variables, nonadherence, and recidivism are shown in a simplified schematic diagram ( Figure 1 ). The diagram is consistent with evidence that patients with a criminal history are at increased risk of both repeated incarceration and hospitalization ( 73 ). As illustrated in Figure 1 , the likelihood of treatment nonadherence increases as the number of individual and service-system risk variables increases. Without appropriate treatment and support services, high-risk adults with psychotic disorders are more likely to exhibit problematic behaviors, such as loitering, trespassing, public intoxication, agitation, and verbal or physical assaultiveness. Such behaviors commonly go unreported. However, they can also result in emergency room intervention or arrest, depending upon who intervenes and how the intervention is conducted.

If a patient is taken to an emergency room, the decision of whether to hospitalize is largely based on whether the patient is determined to be dangerous to self or others. If hospitalized, patients are typically treated for five to seven days with sedating psychotropic medications and discharged with a follow-up appointment at the local community mental health center. In the absence of appropriate intervention after discharge, patients with multiple risk factors are likely to stop their medications, resume their use of illegal drugs and alcohol, and return to living on the streets. Such patients are at risk of continuing the cycle of problematic behaviors, arrest or emergency room intervention, and persisting nonadherence.

If a patient is arrested instead of taken to an emergency room, several issues will determine whether that individual will become incarcerated. Lack of appropriate treatment and support services can contribute to this outcome by decreasing the resources necessary for successful jail diversion. Other variables, such as the crime committed, laws of the local jurisdiction, and skill of the lawyers involved, can affect outcomes independently of individual risk variables or the presence of treatment services. In the absence of adequate follow-up services upon release from custody, patients are likewise at increased risk of continuing the cycle of nonadherence and recidivism.

How to prevent jail and hospital recidivism

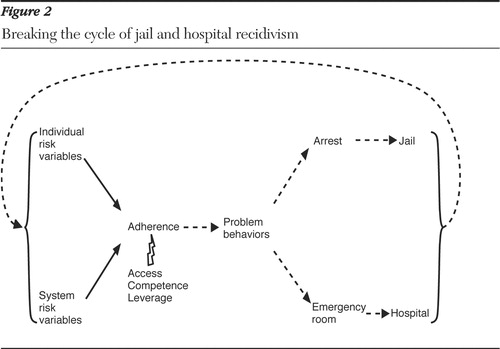

If treatment nonadherence and recidivism are the result of both individual and service-system risk variables, then intervention strategies must address variables at both levels. This capability is important because the relative contribution of each level will vary between individuals. On the basis of this conceptualization, preventing recidivism among individuals with psychotic disorders requires three necessary elements of intervention: competent care, access to services, and legal leverage.

Competent care

Usual community mental health services are unlikely to prevent incarceration among adults with psychotic disorders ( 74 ), particularly among those with a criminal history dating to adolescence ( 75 ). Although core clinical competencies for preventing criminal recidivism have yet to be established, clinicians should be knowledgeable about evidence-based treatments for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders ( 17 , 18 ). However, clinicians must also be familiar with cognitive-behavioral interventions that target antisocial cognition, attitudes, and behavior patterns ( 76 , 77 , 78 ) and be able to assist patients in connecting to community resources ( 79 ). It is likewise important that clinicians understand the process of behavior change and are skilled in using motivational interviewing and behavioral strategies to promote adherence ( 80 , 81 , 82 ). These competencies can result in the establishment of a positive therapeutic alliance, a strong predictor of health outcomes in schizophrenia and other mental illnesses ( 83 , 84 ). In addition, clinicians should be knowledgeable about the criminal justice system and prepared to work in partnership with representatives of the criminal justice system in order to utilize legal leverage if necessary.

Access to service s

Even the most competent care is ineffective if it is inaccessible. Lack of access to evidence-based treatments remains a significant service-system issue for adults with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders ( 4 ). In addition, interventions to identify and address antisocial cognition and attitudes are rarely available to such individuals, even among those with a substantial criminal history ( 69 ). Health care providers and policy makers must recognize that ensuring access to services that target modifiable risk factors is essential in order to prevent criminal recidivism. Treatment and support services should be delivered in as comprehensive and integrated a manner as possible to minimize the fragmentation of care that is experienced by many patients in community settings. Such services must utilize eligibility criteria that include rather than exclude patients with multiple risk factors. For example, patients should not be prematurely discharged from necessary services because of nonadherence. Crisis services, including outreach, should be available around the clock to ensure access to care on evenings and weekends, times when problem behaviors typically emerge. Coordination of mental health and criminal justice services is also important in order to provide access to care for patients who move between systems ( 73 ). When patients are released from jail, access to community services can be enhanced by ensuring that patients are enrolled in Medicaid ( 85 ).

Legal leverage

Despite the consistent delivery of care that is highly accessible and clinically competent, some patients will continue to refuse treatment. Although several different forms of leverage can be used to promote adherence in community settings ( 86 , 87 ), the involvement of patients in the criminal justice system presents the option of legal leverage. Legal leverage is commonly used to address nonadherence, particularly among patients with a history of physically assaultive behavior ( 88 ). However, there is currently no widely accepted definition or standardized approach to using legal leverage. Legal leverage can be understood as having two components: the presence of legal authority and the procedure of how that authority is utilized. In general, legal leverage involves requiring persons with psychotic disorders to choose between treatment and supervision or more severe legal consequences for behaviors resulting from psychosis and co-occurring risk factors. Mental health professionals can lay the groundwork for utilizing legal leverage by establishing collaborative partnerships with probation or parole officers, judges, or police, depending upon a patient's legal involvement and the resources available locally. Partnerships should be based on a shared belief in the value of treatment as an alternative to incarceration and a shared commitment to utilizing problem-solving rather than punitive approaches to behavioral problems. In the absence of such procedural underpinnings, the presence of legal authority can result in an increased risk of incarceration ( 89 ).

The combined impact of access to services, competent care, and legal leverage is illustrated in Figure 2 . By addressing individual and service-system risk variables and promoting treatment adherence, these elements can break the cycle of repeated incarceration and hospitalization among adults with psychotic disorders.

Promoting long-term improvement

Although legal leverage combined with accessible, competent treatment can interrupt the cycle of recidivism, lasting behavioral change is unlikely to occur unless patients become active participants in their own care. A potentially useful model for promoting treatment engagement among adults with psychotic disorders is the self-determination theory of behavior change. According to self-determination theory, treatment motivation may be either controlled or autonomous ( 90 , 91 ). Autonomous motivation for taking medication, for instance, means that patients freely choose to take medication because they believe it is personally important to their well-being ( 92 ). Studies of conditions that are associated with treatment adherence problems, such as alcoholism ( 93 ), opioid dependence ( 94 ), nicotine dependence ( 95 ), and obesity ( 96 ), have confirmed that long-term behavioral change is associated with autonomous motivation. In studies of adults with psychotic disorders, legal leverage is associated with improved adherence ( 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 9 7) but less so when it is associated with perceived coercion ( 98 , 99 ). For example, in Elbogen and colleagues' ( 25 ) recent study of outpatient commitment and adherence, nonadherent participants perceived legal leverage as significantly more coercive compared with those who were adherent. According to self-determination theory, potentially coercive interventions, such as legal leverage, are more likely to promote autonomous motivation if conducted in a manner in which patients receive empathy, options, and a clear rationale about the decisions made ( 92 ).

These qualities are similar to those that promote "procedural justice" within mental health court settings. Procedural justice, or perceived fairness of the court process by the patient, has been associated with low levels of perceived coercion despite the use of legal leverage ( 100 , 101 ). Similar findings have been reported with the process of involuntary hospitalization ( 87 ). Thus legal leverage will be most effective at promoting active treatment engagement if applied not only in combination with accessible, competent care but also in a manner that supports patient autonomy to the extent allowable by each patient's circumstances.

Conceptual issues

The aim of this conceptual framework is to support a basic understanding of the relationships between risk variables, nonadherence, recidivism, and necessary elements of prevention. The diagram in Figure 1 has been simplified for this purpose. For example, although it presents risk variables that are associated with recidivism, it does not depict the many protective variables that operate along with them. In addition, risk variables, such as lack of family support, lack of appropriate housing, and lack of vocational opportunities, are represented within individual and service-system pathways rather than within a separate social-environmental pathway. Also, patients are commonly transferred from jails to hospitals and vice versa, although these pathways are not illustrated in the figure.

Although nonadherence is conceptualized as the main mediator for risk variables and a primary target for intervention, risk variables and treatment interventions are likely to operate through additional mechanisms. Recidivism can still occur in the presence of treatment adherence, and interventions can affect recidivism rates independently of adherence ( 102 ). However, the central role of treatment nonadherence makes it a key focus of intervention. Although this conceptual framework appears to define treatment adherence as a unitary construct, separate dimensions, such as taking medications and attending appointments, may affect outcomes differently. Finally, although this conceptualization supports the use of interventions that address antisocial personality features, the application of such interventions among adults with psychotic disorders requires further study.

Conclusions and future directions

Several approaches to preventing criminal recidivism among adults with psychotic disorders have emerged in recent years, but few put the principle of combining legal leverage with accessible, competent care into daily practice. The current practice of mandating patients with multiple recidivism risk factors to receive "treatment as usual" is questionable from both clinical and ethical standpoints. Although solutions may ultimately require fundamental changes in health care funding, further work is needed to develop intervention strategies that address both individual and service-system risks of recidivism. The conceptual framework described here suggests that combining legal leverage with accessible, competent care is critical to preventing recidivism among adults with psychotic disorders. Research is needed to further define and test these intervention elements as foundations for future service delivery efforts.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The author thanks the following colleagues for their suggestions and support during the development of this article: Steven Belenko, Ph.D., Eric D. Caine, M.D., Catherine Cerulli, J.D., Ph.D., Yeates Conwell, M.D., John F. Crilly, Ph.D., Paul Duberstein, Ph.D., Steven Erickson, J.D., Ph.D., Edward Latessa, Ph.D., Kim T. Mueser, Ph.D., Robert L. Weisman, D.O., and Geoffrey C. Williams, M.D., Ph.D. This article is dedicated in memory of Joseph W. Lamberti, M.D.

The author reports no competing interests.

1. Butterfield F: Prisons replace hospitals for the nation's mentally ill. New York Times, Mar 5, 1998, p 1Google Scholar

2. Ill-Equipped: US Prisons and Offenders With Mental Illness. New York, Human Rights Watch, 2003. Available at www.hrw.orgGoogle Scholar

3. Criminalization of Mental Illness. National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2001. Available at www.nami.org/content/contentgroups/policy/criminalization2001.pdfGoogle Scholar

4. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

5. James DJ: Profile of Jail Inmates. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 2002. Available at www.nicic.org/library/serial881Google Scholar

6. Robins LN, Regier DA: Psychiatric Disorders of America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

7. Motiuk LL, Porporino FJ: The Prevalence, Nature and Severity of Mental Health Problems Among Federal Male Inmates in Canadian Penitentiaries. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, Correctional Service of Canada, 1991Google Scholar

8. Brugha T, Singleton N, Meltzer H, et al: Psychosis in the community and in prisons: a report from the British national survey of psychiatric morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:774–780, 2005Google Scholar

9. Wallace C, Mullen P, Burgess P: Criminal offending in schizophrenia over a 25-year period marked by deinstitutionalization and increasing prevalence of comorbid substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:715–727, 2004Google Scholar

10. Teplin LA: Criminalizing mental disorder: the comparative arrest rate of the mentally ill. American Psychologist 39:794–803, 1984Google Scholar

11. Valdiserri E, Carroll K, Hartl A: A study of offenses committed by psychotic inmates in a county jail. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:163–166, 1986Google Scholar

12. Walsh E, Buchanan A, Fahy T: Violence and schizophrenia: examining the evidence. British Journal of Psychiatry 180:490–495, 2002Google Scholar

13. Schwartz R, Reynolds C, Austin J, et al: Homicidality in schizophrenia: a replication study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 73:74–77, 2003Google Scholar

14. Krakowski M: Schizophrenia with aggressive and violent behaviors. Psychiatric Annals 35:44–49, 2005Google Scholar

15. Rosack J: Patient charged with murder of schizophrenia expert. Psychiatric News 41 (19):1–7, 2006Google Scholar

16. Ditton PM: Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 1999. Available at www. ojp.usdoj.gov/bjsGoogle Scholar

17. Lehman A, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan R, et al: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:193–217, 2004Google Scholar

18. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(Feb suppl):1–56, 2004Google Scholar

19. Mueser K, Bond G, Drake R, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37–74, 1998Google Scholar

20. Bond G, Drake R, Mueser K, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141–159, 2001Google Scholar

21. Hiday VA: Outpatient commitment: the state of empirical research on its outcomes. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:8–32, 2003Google Scholar

22. Lamberti JS, Weisman RL: Persons with severe mental disorders in the criminal justice systems: challenges and opportunities. Psychiatric Quarterly 75:151–164, 2004Google Scholar

23. Draine J, Solomon P: Describing and evaluating jail diversion services for persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:56–61, 1999Google Scholar

24. Steadman H, Barbera S, Dennis D: A national survey of jail diversion programs for mentally ill detainees. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1109–1113, 1994Google Scholar

25. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS: Effects of legal mechanisms on perceived coercion and treatment adherence among persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:629–637, 2003Google Scholar

26. Hiday V, Scheid-Cook T: Outpatient commitment for "revolving door" patients: compliance and treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:83–88, 1991Google Scholar

27. Swartz M, Swanson J, Wagner H, et al: Effects of involuntary outpatient commitment and depot antipsychotics on treatment adherence in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 189:583–592, 2001Google Scholar

28. Swanson J, Swartz M, Borum R, et al: Involuntary out-patient commitment and reduction of violent behavior in persons with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:324–331, 2000Google Scholar

29. Skeem JL, Louden JE: Toward evidence-based practice for probationers and parolees mandated to mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 57:333–342, 2006Google Scholar

30. Steadman HJ, Naples M: Assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for persons with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 23:163–170, 2005Google Scholar

31. What Can We Say About the Effectiveness of Jail Diversion Programs for Persons With Co-occurring Disorders? Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center, TAPA Center for Jail Diversion, 2004Google Scholar

32. Swanson J, Borum R, Swartz M, et al: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce arrests among persons with severe mental illness? Criminal Justice and Behavior 28:156–189, 2001Google Scholar

33. Swartz MS, Swanson JW: Involuntary outpatient commitment, community treatment orders, and assisted outpatient treatment: what's in the data? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 49:585–591, 2004Google Scholar

34. Steadman H, Deane M, Morrissey J: A SAMHSA research initiative assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 50:1620–1623, 1999Google Scholar

35. Erickson SK, Campbell A, Lamberti JS: Variations in mental health courts: challenges, opportunities, and a call for caution. Community Mental Health Journal 42:335–344, 2006Google Scholar

36. Daly R: Prison mental health crisis continues to grow. Psychiatric News 41(20):1, 2006Google Scholar

37. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL: Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Services 52:1039–1045, 2001Google Scholar

38. Torrey EF: Out of the Shadows: Confronting America's Mental Illness Crisis. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

39. Kennedy S: A practitioner's guide to responsivity: maximizing treatment effectiveness. Journal of Community Corrections Winter:7–30, 2003Google Scholar

40. Taxman F, Marlowe D: Risk, needs, responsivity: in action or inaction? Crime and Delinquency 52:3–6, 2006Google Scholar

41. Andrews DA, Bonta J: Psychology of Criminal Conduct. Cincinnati, Ohio, Anderson Publishing, 2003Google Scholar

42. Andrews DA, Bonta J, Wormith J: The recent past and near future of risk and/or need assessment. Crime and Delinquency 52:7–27, 2006Google Scholar

43. Bonta J, Law M, Hanson K: The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 123:123–142, 1998Google Scholar

44. Regier D, Farmer M, Rae D, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 264:2511–2518, 1990Google Scholar

45. Moran P, Hodgins S: The correlates of comorbid antisocial personality disorder in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:791–802, 2004Google Scholar

46. Draine J, Salzer M, Culhane D, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573, 2002Google Scholar

47. Solomon P, Draine J: Using clinical and criminal involvement factors to explain homelessness among clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:75–87, 1999Google Scholar

48. McQuistion H, Finnerty M, Hirschowitz J, et al: Challenges for psychiatry in serving homeless people with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 54:669–676, 2003Google Scholar

49. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA: Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:42–48, 2004Google Scholar

50. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Essock S, et al: The social-environmental context of violent behavior in persons treated for severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 92:1523–1531, 2002Google Scholar

51. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al: A national study of violent behavior in persons with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:490–499, 2006Google Scholar

52. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J: Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:566–572, 2000Google Scholar

53. Hodgins S, Hiscoke U, Freese R: The antecedents of aggressive behavior among men with schizophrenia: a prospective investigation of patients in community treatment. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 21:523–546, 2003Google Scholar

54. McNiel DE, Eisner JP, Binder RL: The relationship between command hallucinations and violence. Psychiatric Services 51:1288–1292, 2000Google Scholar

55. Joyal CC, Putkonen A, Paavola P, et al: Characteristics and circumstances of homicidal acts committed by offenders with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 34:433–442, 2004Google Scholar

56. Sung H, Belenko S, Feng L: Treatment compliance in the trajectory of treatment progress among offenders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 20:153–162, 2001Google Scholar

57. Haynes R: Compliance in Health Care. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979Google Scholar

58. Nose M, Barbui C, Tansella M: How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programmes? A systematic review. Psychological Medicine 33:1149–1160, 2003Google Scholar

59. Lieberman J, Stroup T, McEvoy J, et al: Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 353:1209–1223, 2005Google Scholar

60. Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, et al: Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:453–460, 2006Google Scholar

61. Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P: Predicting engagement with services for psychosis: insight, symptoms and recovery style. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:123–128, 2003Google Scholar

62. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Medication nonadherence and substance abuse in psychotic disorders: impact of depressive symptoms and social stability. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 193:673–679, 2005Google Scholar

63. Kampman O, Laippala P, Vaananen J, et al: Indicators of medication compliance in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Research 110:39–48, 2002Google Scholar

64. Pitschel-Walz G, Bauml J, Bender W, et al: Psychoeducation and compliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: results of the Munich Psychosis Information Project Study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67:443–452, 2006Google Scholar

65. Young JL, Spitz RT, Hillbrand M, et al: Medication adherence failure in schizophrenia: a forensic review of rates, reasons, treatments, and prospects. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry 27:426–444, 1999Google Scholar

66. Day J, Bentall R, Roberts C, et al: Attitudes toward antipsychotic medication: the impact of clinical variables and relationships with health professionals. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:717–724, 2005Google Scholar

67. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: Taking the wrong drugs: the role of substance abuse and medication noncompliance in violence among severely mentally ill individuals. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33(suppl 1):S75–S80, 1998Google Scholar

68. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: A randomized controlled trial of outpatient commitment in North Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:325–329, 2001Google Scholar

69. Lamberti JS, Weisman RL, Faden DI: Forensic assertive community treatment: preventing incarceration of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1285–1293, 2004Google Scholar

70. Skeem JL, Monahan J, Mulvey EP: Psychopathy, treatment involvement, and subsequent violence among civil psychiatric patients. Law and Human Behavior 26:577–603, 2002Google Scholar

71. Mueser KT, Crocker AG, Frisman LB, et al: Conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder in persons with severe psychiatric and substance use disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:626–636, 2006Google Scholar

72. Tengstrom A, Hodgins S, Kullgren G: Men with schizophrenia who behave violently: the usefulness of an early- versus late-start offender typology. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:205–218, 2001Google Scholar

73. Prince JD: Incarceration and hospital care. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194:34–39, 2006Google Scholar

74. Fisher WH, Packer IK, Simon LJ, et al: Community mental health services and the prevalence of severe mental illness in local jails: are they related? Administration and Policy in Mental Health 27:371–382, 2000Google Scholar

75. Hodgins S, Muller-Isberner R: Preventing crime by people with schizophrenic disorders: the role of psychiatric services. British Journal of Psychiatry 185:245–250, 2004Google Scholar

76. Allen L, Mackenzie D, Hickman L: The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral treatment for adult offenders: a methodological quality-based review. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 45:498–514, 2001Google Scholar

77. Lipsey M, Chapman G, Landenberger N: Cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 578:144–157, 2001Google Scholar

78. Landenberger N, Lipsey M: The positive effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for offenders: a meta-analysis of factors associated with effective treatment. Journal of Experimental Criminology 1:451–476, 2005Google Scholar

79. Draine J, Wolff N, Jacoby JE, et al: Understanding community re-entry of former prisoners with mental illness: a conceptual model to guide new research. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 23:689–707, 2005Google Scholar

80. Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, et al: Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1653–1664, 2002Google Scholar

81. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC: In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist 47:1102–1114, 1992Google Scholar

82. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

83. Martin D, Garske J, Davis M: Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:438–450, 2000Google Scholar

84. Frank A, Gunderson J: The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: relationship to course and outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:228–236, 1990Google Scholar

85. Morrissey JP, Steadman HJ, Dalton KM, et al: Medicaid enrollment and mental health service use following release of jail detainees with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 57:809–815, 2006Google Scholar

86. Monahan J, Redich A, Swanson J, et al: Use of leverage to improve adherence to psychiatric treatment in the community. Psychiatric Services 56:357–358, 2005Google Scholar

87. Monahan J, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Mandated community treatment: beyond outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:1198–1205, 2001Google Scholar

88. Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, Monahan J, et al: Violence and leveraged community treatment for persons with mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1404–1411, 2006Google Scholar

89. Solomon P, Draine J, Marcus SC: Predicting incarceration of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatric Services 53:50–56, 2002Google Scholar

90. Deci E, Ryan R: The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11:227–268, 2000Google Scholar

91. Ryan R, Connell J: Perceived locus of causality and internalization: examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57:749–761, 1989Google Scholar

92. Williams GC, Rodin G, Ryan R, et al: Autonomous regulation and adherence to long-term medical regimens in adult outpatients. Health Psychology 17:269–276, 1998Google Scholar

93. Ryan R, Plant R, O'Malley S: Initial motivations for alcohol treatment: relations with patient characteristics, treatment involvement, and dropout. Addictive Behaviors 20:279–297, 1995Google Scholar

94. Zeldman A, Ryan R, Fiscella K: Client motivation, autonomy support and entity beliefs: their role in methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 23:675–696, 2004Google Scholar

95. Williams GC, McGregor HA, Sharp D, et al: Testing a self-determination theory intervention for motivating tobacco cessation: supporting autonomy and competence in a clinical trial. Health Psychology 25:91–101, 2006Google Scholar

96. Williams GC, Grow V, Freedman Z, et al: Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70:115–126, 1996Google Scholar

97. Appelbaum P: Assessing Kendra's law: five years of outpatient commitment in New York. Psychiatric Services 56:791–801, 2005Google Scholar

98. Rain S, Steadman H, Robbins P: Perceived coercion and treatment adherence in an outpatient commitment program. Psychiatric Services 54:399–401, 2003Google Scholar

99. Farabee D, Shen H, Sanchez S: Program-level predictors of antipsychotic medication adherence among parolees. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 48:561–571, 2004Google Scholar

100. Poythress N, Petrila J, McGaha A, et al: Perceived coercion and procedural justice in the Broward mental health court. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 25:517–533, 2002Google Scholar

101. Winick BJ: Outpatient commitment: a therapeutic jurisprudence analysis. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:107–144, 2003Google Scholar

102. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, George LK, et al: Interpreting the effectiveness of involuntary outpatient commitment: a conceptual model. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry 25:5–16, 1997Google Scholar