Consent Form Readability and Educational Levels of Potential Participants in Mental Health Research

The doctrine of informed consent constitutes the foundation of ethical clinical research. Informed consent consists of three parts: voluntariness, disclosure, and competence ( 1 ). Most research studies provide potential participants with consent forms that disclose the study's purpose, procedures, and risks and benefits. Although written forms are not the only means of communicating information to potential participants, they are typically more complete than verbal disclosures and are relied on by institutional review boards to ensure that all necessary information is conveyed. With this information participants presumably make an "informed" and voluntary decision about whether to participate. The validity of the consent obtained depends in part on whether participants understand what is being disclosed.

U.S. literacy surveys estimate that at least 40 million adults are functionally illiterate and another 50 million are only marginally literate ( 2 ). Approximately 70% of adults with a self-reported mental health problem are either functionally illiterate or marginally literate ( 3 ). Furthermore, adults with mental illness who are literate read three to five grade levels below that expected by their level of education ( 4 , 5 , 6 ). Thus the maximum completed grade level serves as a conservative estimate of reading ability, with any discrepancy likely erring on the side of overestimation.

Studies reveal that informed consent forms used in general medical research are often written at a reading level that exceeds that of study participants ( 7 ), the general population ( 8 ), and the mandates of institutional review boards ( 9 ). However, to our knowledge no study has compared the readability of consent forms used in mental health research with the educational levels of potential study participants.

The Massachusetts Department of Mental Health provides services for and sponsors research involving persons with mental illness. All research studies must be approved by the department's Central Office Research Review Committee. The committee's guidelines for informed consent procedures mandate that consent forms "be written in a language and in terms understandable to the research subject" ( 10 ). Nevertheless, it is possible that the forms used in Massachusetts Department of Mental Health research are written at a reading level that is higher than that achieved by potential study participants.

To investigate this possibility we compared the readability of informed consent forms used in research studies approved by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health between 1993 and 2004 with the maximum attained grade level of adults who were eligible to participate. We stratified the readability scores on the basis of the risk level for each study.

Methods

The study was approved by the Central Office Research Review Committee and by the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Potential study participants

The Massachusetts Department of Mental Health provided the maximum completed U.S. grade level for all adults (19 years or older) receiving services as of September 2005. Of these 17,345 adults, the maximum completed grade level was known for 12,848. Eligibility for services requires that an adult have a severe and persistent major mental disorder that has lasted, or is expected to last, at least one year and has resulted in functional impairment in major life activities. No personal identification or confidential information was requested or provided.

Informed consent forms

All 172 informed consent forms from completed research studies that were approved by the Central Office Research Review Committee between 1993 and 2004 were provided by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Eighteen forms were excluded: six were for studies involving family members, caregivers, or medical professionals, and 12 were earlier, but otherwise identical, versions of forms already included.

The remaining 154 forms were separated into three groups according to risk levels assigned by the Central Office Research Review Committee. Level 1 studies are not likely to expose participants to any risk greater than that encountered in their normal life—that is, minimal risk studies. Level 3 studies are placebo-controlled or symptom-provocation studies. And level 2 studies are those with a level of risk that exceeds that of level 1 but does not reach the magnitude of level 3. Level 2 studies may involve risks such as loss of confidentiality, need for hospitalization, and anxiety associated with recounting personal history. In all risk determinations, definitions provided by federal research regulations ( 11 ) were taken into account.

Each informed consent form was scanned into a Microsoft Word document by using OmniPage Pro, a program designed to capture scanned text. The documents were each compared with the original forms and corrected for any scanning errors.

The readability of each document was analyzed by using Readability Calculations, version 5.1, a software package available from Micro Power and Light. Because the program considers periods, exclamation points, and question marks only as end-sentence punctuation and considers periods as always denoting the end of a sentence, small grammatical edits were made to some of the text. These included replacing all colons and semicolons separating independent clauses with periods and eliminating periods used as abbreviations (for example, "M.D." became "MD" and "e.g." became "eg").

Many consent forms contained tables, headings, or other text that were not in sentence format—for example, scheduling tables for dosing of medication or tables listing addresses of contact persons. Such devices were omitted from our analysis. Forms exceeding six single-spaced typed pages were divided into two parts because of a limitation in the amount of text the program could analyze in a single submission. In these instances the mean of the two parts was calculated to obtain the readability of that form.

For each informed consent form, readability scores were assigned by using four readability formulas: the Flesch Reading Ease Score (FRES), the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Index (FKGL), the Fog Index, and the Fry Graph. The FRES and the FKGL both determine readability by examining the average number of words per sentence and the average number of syllables per word. The FRES score is a number from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating easier readability. The FKGL, the Fog Index, and the Fry Graph each give the U.S. grade level required to read text, with a higher grade level indicating more difficult readability.

Possible scores for the FKGL and Fog Index formulas range from a minimum of grade 1 but have no maximum grade level that can be calculated. However, both formulas were originally designed to measure readability of elementary and secondary school texts. Thus one may expect scores falling beyond the 12th grade level to have less practical validity. Both the FRES and FKGL have been used extensively to calculate readability of informed consent forms ( 7 , 8 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ), patient education materials ( 16 ), and medical literature ( 17 ). The formula used by the Fog Index to calculate readability level uses the average sentence length and the number of words with three or more syllables to give a U.S. grade level. This method has also been used to analyze readability of informed consent forms ( 12 , 14 , 15 ). The Fry Graph plots the average number of sentences against the average number of syllables to determine the U.S. grade level. Possible scores range from grade 1 to grade 16. For text with a calculated Fry readability score beyond grade 16, no grade level is assigned. The Fry Graph has been used to calculate informed consent form readability as well ( 13 , 18 ).

Analyses

We performed a descriptive analysis of the range, mean, and standard deviation for the readability scores determined by the four formulas.

A Kruskal-Wallis test determined if the readability scores from each formula varied by risk level. For each formula, the Kruskal-Wallis test first assigned a rank to the readability score of each informed consent form. It then provided the mean rank of scores for each risk level. A chi square analysis determined the degree of difference between risk-level ranks and the mean of all the ranks.

Results

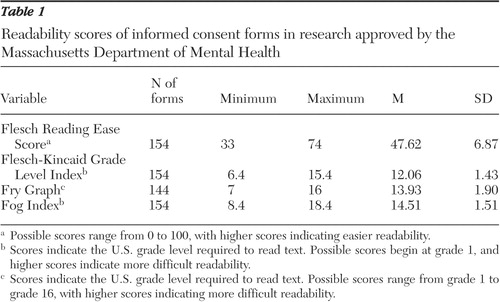

Table 1 shows the range and average readability of the informed consent forms as calculated by each readability formula. The mean FRES for 154 tested forms was 47.6, which indicated a "difficult" reading level, with a corresponding mean FKGL score at a 12th-grade reading level. The mean Fog Index readability for 154 forms was a 14.5th-grade reading level. Ten informed consent forms fell beyond the 16th grade level on the Fry Graph; the mean score for the remaining 144 informed consent forms was a 13.9th-grade reading level.

|

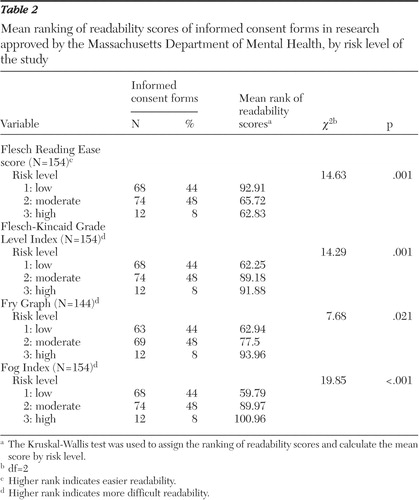

The readability scores were assigned a ranking and then grouped by risk level. Of the 154 forms, 68 were for risk level 1 studies, 74 were for risk level 2 studies, and 12 were for risk level 3 studies. Table 2 shows the mean rank of readability scores by risk level for each formula. For each formula tested, the mean rank of readability scores increased with increasing risk level, indicating that the consent forms used in studies with higher risk were more difficult to read. The chi square analysis showed that the difference in ranking was statistically significant between the stratified risk levels.

|

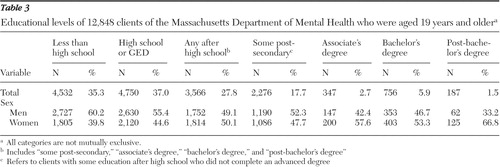

Table 3 shows the maximum attained educational level for the 12,848 adults receiving services from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Thirty-five percent did not graduate from high school (included in this category are 1,075 persons who received a "certificate of completion" in lieu of a diploma). Thirty-seven percent graduated from high school or obtained their GED but had no further education, and 28% had some education beyond the 12th grade.

|

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined 154 consent forms approved by the institutional review board of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health between 1993 and 2004 and found that the average readability ranged from grade 12 to 14.5. Furthermore, consent forms became more difficult to read as the risk level of the study increased. The significance of this finding is emphasized when placed in context with the educational data for adults eligible to participate in the studies. Even by the most conservative estimate (that is, the FKGL, which yielded the lowest overall mean readability score), approximately 35% lacked the educational level required to read the average informed consent form. Considering that persons with mental illness tend to read three to five grade levels below their maximum level of education, the discrepancy we found between the readability of consent forms and the reading ability of potential study participants may actually be underestimated. This discrepancy calls into question the utility of informed consent forms in conveying to participants the information that they need to make informed judgments about whether to enter a study.

This study has several limitations. First, the educational levels of clients that were taken from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health database may differ from those of the actual participants in the research studies approved by the department. It is possible that individuals who consented and participated in the research studies had higher reading abilities and therefore were more likely to comprehend the consent forms. In fact, some reports involving non-mentally ill adults suggest that individuals with lower levels of education are less likely to consent to participate in research studies ( 19 , 20 ). If this were also true of those with mental illness, our findings would overestimate the percentage of study participants who are unable to read the average consent form. In addition, we note the temporal discrepancy between the data on educational levels gathered from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health in September 2005 and the informed consent forms of studies conducted between 1993 and 2004. These educational levels may not represent the individuals who were eligible to participate in earlier studies; however, we are not aware of any significant change in the educational characteristics of the population receiving services over time. Furthermore, the educational attainments of this population do not necessarily represent those of patients with mental illness in general.

Another important drawback of our study lies with the use of readability formulas. Although the formulas we chose have been used extensively in medical studies looking at informed consent forms, health-related education materials intended for patient consumption, and even articles published in medical journals, they clearly have limitations. Most formulas (including those used in our study) do not take into account the difficulty of vocabulary used in text; instead they focus on "surface" characteristics. However, we found that nearly all of the forms reviewed included complex medical vocabulary that is not likely to be well understood by lay persons, much less those with serious mental illness.

We also note that readability formulas were originally designed to assess elementary and secondary school texts. Thus scores falling beyond the 12th grade level may be considered to have less practical validity than those at or below the 12th grade level. Furthermore, our calculations do not take into account the length of informed consent forms. Many contained more than ten single-spaced, typed pages, especially studies at risk level 3. Recent research on the readability of text has highlighted the importance of coherence, the logical structure of text, and cohesion—that is, how well different parts of the text relate to one another ( 21 ). Although coherence and cohesion are not captured by the readability formulas currently available, at least one group is seeking to change that ( 22 ). As noted previously, a number of the consent forms we studied provided tables that were not included in our analyses. Forms using such organizational devices, presumably designed to improve comprehension of study participants, may "score higher" on coherence and cohesion than others. In fact, some commentators have recommended the use of similar devices to supplement traditional text-based consent forms ( 23 ).

Finally, we are aware that use of any form is generally considered but one part of a larger informed consent process. Many of the consent forms we examined included statements that either encouraged prospective participants to ask questions or asked them to sign a statement indicating that all questions had been answered. Although verbal interaction in concert with reading an informed consent form is likely to improve comprehension, it seems reasonable to ask that forms be readable, especially for the target population.

On the other hand, we believe that it would be unfortunate for institutional review boards simply to mandate that informed consent forms meet certain readability criteria. Notwithstanding the mandates many institutional review boards have already imposed, it is not clear whether forms can be written at a sufficiently low level to match the educational level of prospective participants. Nor is it clear whether this would guarantee comprehension. At least one study suggests that patients with schizophrenia have poorer reading comprehension, compared with IQ-matched controls ( 24 ). Kovnick and others ( 25 ) examined 27 patients with schizophrenia and found that negative symptoms correlated strongly with poor understanding and appreciation (two of the four components in decision-making capacity); however, at least a third of the patients studied performed as well as the control group. Two studies found that the use of simplified consent forms for participants in nonpsychiatric studies did not improve comprehension or recall testing. However, participants did report that using simplified forms lowered anxiety and increased satisfaction ( 16 , 26 ). These data suggest that comprehension during the informed consent process may need to be assessed on an individual basis.

In fact, efforts have been made by a number of groups to develop instruments to measure the comprehension of individual study participants. Some instruments assess multiple aspects of participants' decisional capacity—for example, the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research ( 27 ). Other instruments provide more rapid assessments of understanding of a more limited range of disclosed information—for example, the Evaluation of Signed Consent ( 28 ). In such cases, participants who do not meet the threshold scores could undergo educational training on the details of research studies in general and those specific to their respective study. If on repeat testing they still fail to demonstrate the capacity to understand relevant information, they would be excluded from participating in the study. Although data are not available to indicate how commonly these practices are used in mental health research today, the authors are aware of a number of studies, including the multisite Clinical Antipsychotic Trials in Intervention Effectiveness study of antipsychotic medications, that have employed these approaches ( 29 ).

The precise means to ensure adequate informed consent procedures for those with mental illness remain elusive. Extreme approaches have been suggested at both ends of the continuum. One could eliminate high-risk research involving persons with serious mental illness, but this seems unreasonable because testing indicates that many persons with mental illness have the requisite capacity to consent ( 30 ). At the other end of the spectrum at least one philosopher has suggested that it is our current understanding of the informed consent process that must change ( 31 ). A good-faith effort on the part of institutional review boards and researchers to inform study participants should suffice for what is unattainable: the truly informed study participant. This philosopher's argument is partly utilitarian: to continue on our present course "threatens to bring enrollment in many ethical clinical trials to a near standstill." At this point, however, in the absence of sufficient data to determine the extent to which participants' capacities can be improved by educational interventions, this conclusion seems decidedly premature. But it does seem clear that without some change in the informed consent process, a large number of persons participating in mental health research are likely to continue to be at risk of being uninformed.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Berg JW, Appelbaum PS, Lidz CW, et al: Informed Consent: Legal Theory and Clinical Practice, 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

2. Kirsch IS, United States Office of Educational Research and Improvement, Educational Testing Service, et al: Adult Literacy in America: A First Look at the Results of the National Adult Literacy Survey. Washington, DC, US Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, 1993Google Scholar

3. Sentell TL, Shumway MA: Low literacy and mental illness in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:549-552, 2003Google Scholar

4. Baker FM, Johnson JT, Velli SA, et al: Congruence between education and reading levels of older persons. Psychiatric Services 47:194-196, 1996Google Scholar

5. Christensen RC, Grace GD: The prevalence of low literacy in an indigent psychiatric population. Psychiatric Services 50:262-263, 1999Google Scholar

6. Currier GW, Sitzman R, Trenton A: Literacy in the psychiatric emergency service. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 189:56-58, 2001Google Scholar

7. Williams BF, French JK, White HD, et al: Informed consent during the clinical emergency of acute myocardial infarction (HERO-2 consent substudy): a prospective observational study. Lancet 361:918-922, 2003Google Scholar

8. Paasche-Orlow MK, Taylor HA, Brancati FL: Readability standards for informed consent forms as compared with actual readability. New England Journal of Medicine 348:721-726, 2003Google Scholar

9. Jackson RH, Davis TC, Bairnsfather LE, et al: Patient reading ability: an overlooked problem in health care. Southern Medical Journal 84:1172-1175, 1991Google Scholar

10. Massachusetts Department of Mental Health Regulations, 104 CMR 31.05, Review Standards, 5(b), 2003Google Scholar

11. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45, Part 46, 2005Google Scholar

12. Goldstein AO, Frasier P, Curtis P, et al: Consent form readability in university-sponsored research. Journal of Family Practice 42:606-611, 1996Google Scholar

13. Hammerschmidt DE, Keane MA: Institutional Review Board (IRB) review lacks impact on the readability of consent forms for research. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 304:348-351, 1992Google Scholar

14. Hopper KD, TenHave TR, Hartzel J: Informed consent forms for clinical and research imaging procedures: how much do patients understand? American Journal of Roentgenology 164:493-496, 1995Google Scholar

15. Davis TC, Holcombe RF, Berkel HJ, et al: Informed consent for clinical trials: a comparative study of standard versus simplified forms. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 90:668-674, 1998Google Scholar

16. Kusec S, Brborovic O, Schillinger D: Diabetes websites accredited by the Health on the Net Foundation Code of Conduct: readable or not? Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 95:655-660, 2003Google Scholar

17. Roberts JC, Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW: Effects of peer review and editing on the readability of articles published in Annals of Internal Medicine. JAMA 272:119-121, 1994Google Scholar

18. Philipson SJ, Doyle MA, Gabram SG, et al: Informed consent for research: a study to evaluate readability and processability to effect change. Journal of Investigative Medicine 43:459-467, 1995Google Scholar

19. Lerman C, Rimer BK, Daly M, et al: Recruiting high risk women into a breast cancer health promotion trial. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention 3:271-276, 1994Google Scholar

20. DeLuca SA, Korcuska LA, Oberstar BH, et al: Are we promoting true informed consent in cardiovascular clinical trials? Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 9:54-61, 1995Google Scholar

21. Meyer BJF: Text coherence and readability. Topics in Language Disorders 23:204-224, 2003Google Scholar

22. Graesser AC, McNamara DS, Louwerse MM, et al: Coh-metrix: analysis of text on cohesion and language. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 36:193-202, 2004Google Scholar

23. Campbell FA, Goldman BD, Boccia ML, et al: The effect of format modifications and reading comprehension on recall of informed consent information by low-income parents: a comparison of print, video, and computer-based presentations. Patient Education and Counseling 53:205-216, 2004Google Scholar

24. Hayes RL, O'Grady BM: Do people with schizophrenia comprehend what they read? Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:499-507, 2003Google Scholar

25. Kovnick JA, Appelbaum PS, Hoge SK, et al: Competence to consent to research among long-stay inpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 54:1247-1252, 2003Google Scholar

26. Coyne CA, Xu R, Raich P, et al: Randomized, controlled trial of an easy-to-read informed consent statement for clinical trial participation: a study of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Journal of Clinical Oncology 21:836-842, 2003Google Scholar

27. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR). Sarasota, Fla, Professional Resource Press, 2001Google Scholar

28. DeRenzo EG, Conley RR, Love R: Assessment of capacity to give consent to research participation: state-of-the-art and beyond. Journal of Health Care Law and Policy 1:66-87, 1998Google Scholar

29. Stroup S, Appelbaum PS, Swartz M, et al: Decision-making capacity for research participation among individuals in the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophrenia Research 80:1-8, 2005Google Scholar

30. Carpenter WT, Gold JM, Lahti AC, et al: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:533-538, 2000Google Scholar

31. Sreenivasan G: Does informed consent to research require comprehension? Lancet 362:2016-2018, 2003Google Scholar